Introduction: The Polymath of Antwerp

Joris Hoefnagel (1542–1601), sometimes known as Georg Hoefnagel, stands as a remarkable figure in the landscape of late Renaissance Northern European art. Born in the bustling mercantile hub of Antwerp, he was far more than a painter; his talents encompassed printmaking, miniature painting, draftsmanship, cartography, and even commerce. Flourishing during a period of intense political upheaval and intellectual ferment, Hoefnagel navigated the worlds of art, science, and courtly patronage with exceptional skill and versatility. His legacy is characterized by meticulous observation of the natural world, exquisite miniature painting, and significant contributions to manuscript illumination and the nascent genre of still life painting. He represents one of the last great manuscript illuminators and a vital bridge to the scientific and artistic developments of the 17th century.

Hoefnagel hailed from a prosperous family involved in the diamond and luxury goods trade, a background that afforded him a comprehensive humanist education. He became proficient in multiple languages, possessed musical talents, and even penned poetry. This broad intellectual grounding deeply informed his artistic output, infusing it with layers of meaning, symbolism, and scholarly reference. Though he sometimes described himself as self-taught, evidence suggests he may have received early artistic guidance, possibly from the Antwerp painter Hans Bol, known for his landscapes and genre scenes. Hoefnagel's life and work exemplify the Renaissance ideal of the 'uomo universale,' a multi-talented individual engaged with the diverse currents of his time.

Early Life, Travels, and the Impact of Conflict

Born in 1542 into the affluent household of Jacob Hoefnagel, a dealer in diamonds and tapestries, Joris received an education befitting his station in Antwerp, then a major European center for arts and commerce. His upbringing immersed him in humanist thought, fostering a lifelong curiosity about the world. He traveled extensively during his formative years, visiting France and Spain between 1560 and 1562, experiences that broadened his horizons and likely exposed him to different artistic traditions. He also spent time in England from 1568 to 1569, where he associated with fellow Flemish émigrés.

The relative stability of his early life was shattered by the political and religious turmoil engulfing the Low Countries. The Spanish Fury, the brutal sack of Antwerp by Spanish troops in 1576 (though some accounts suggest an earlier departure around 1567 due to preceding unrest), proved a decisive turning point. The Hoefnagel family suffered significant financial losses, and Joris was compelled to leave his native city. This period of exile, however, seems to have catalyzed his dedication to art and natural study, perhaps as a source of solace and intellectual engagement amidst chaos. His subsequent travels became not just a necessity but a defining feature of his career.

A Peregrinating Artist and Scholar

Following his departure from Antwerp, Hoefnagel embarked on extensive travels that shaped his artistic practice and intellectual network. In 1577, he journeyed south to Italy, accompanied by his friend, the renowned cartographer Abraham Ortelius. Ortelius, creator of the first modern atlas, Theatrum Orbis Terrarum, shared Hoefnagel's interest in geography and precise observation. Their travels took them through Augsburg, Munich, Venice, Rome, and Naples, allowing Hoefnagel to sketch ancient monuments and contemporary cityscapes, some of which would later be incorporated into major cartographic projects.

After his Italian sojourn, Hoefnagel traveled through Germany, Austria, and Bohemia. He found patronage initially at the court of Duke Albert V of Bavaria in Munich, a significant collector and supporter of the arts. Hoefnagel worked for the Bavarian court intermittently between approximately 1578 and 1590. He later settled in Vienna, where he continued his artistic activities. His peripatetic existence put him in contact with a wide range of artists, scholars, and patrons across Europe, enriching his perspective and disseminating his unique style. This constant movement also fueled his interest in topography and the accurate depiction of diverse locales.

The Art of Observation: Natural History Illuminated

One of Joris Hoefnagel's most enduring contributions lies in his incredibly detailed and lifelike depictions of the natural world. Working in an era before the strict separation of art and science, his illustrations of plants, insects, small animals, and marine life are marvels of empirical observation rendered with artistic finesse. He possessed an uncanny ability to capture the specific textures, colors, and forms of his subjects, often presenting them against a plain background or incorporating them into complex allegorical compositions.

His approach was almost scientific in its precision, anticipating the work of later natural history illustrators. He didn't merely copy existing representations; he studied specimens directly, sometimes magnifying tiny details to reveal the intricate beauty of creation. This focus on the minute reflects a broader Renaissance fascination with the microcosm as a reflection of the divine order of the macrocosm. His work in this vein is exemplified by the monumental project known as The Four Elements.

The Four Elements: A Microcosmic Encyclopedia

Commissioned likely during his time serving the Bavarian Dukes or later for Emperor Rudolf II, The Four Elements (Ignis, Aqua, Terra, Aer) is a testament to Hoefnagel's ambition and skill. This multi-volume work, executed primarily between the 1570s and 1580s, comprises hundreds of miniature paintings on vellum, meticulously cataloging the creatures associated with each classical element. Ignis (Fire) features insects, Aqua (Water) depicts fish and marine invertebrates, Terra (Earth) showcases quadrupeds, reptiles, and terrestrial invertebrates, while Aer (Air) presents birds and flying insects.

Each illustration is rendered with astonishing detail and vibrant color, often accompanied by Latin inscriptions, mottoes, or emblems that add layers of symbolic or moral meaning. The project was more than a simple zoological record; it was conceived as a visual encyclopedia, a theatrum naturae reflecting the order, diversity, and wonder of God's creation. These volumes, now primarily housed in the National Gallery of Art in Washington D.C., represent a high point of late Renaissance natural history illustration, blending scientific curiosity with profound artistic sensitivity. They stand alongside the work of contemporaries like the botanist Carolus Clusius, with whom Hoefnagel maintained a friendship.

Master of the Miniature: Technique and Innovation

Hoefnagel excelled in the demanding art of miniature painting, a field requiring immense patience, a steady hand, and meticulous attention to detail. He worked primarily in watercolor and gouache on vellum, materials that allowed for brilliant color saturation and fine linework. His miniatures, often no larger than a postcard, possess a jewel-like quality. He was particularly adept at creating verlichteryen, small, independent miniature paintings intended as collectible objects rather than book illustrations, combining preciousness with pictorial interest.

A notable technical aspect of his work was his innovative use of shell gold. This technique involved grinding gold leaf into a powder, mixing it with a binder (like gum arabic), and applying it with a brush, much like paint. It allowed for delicate highlights, shimmering textures, and intricate gilded details that catch the light beautifully. Hoefnagel was among the earliest artists to exploit the visual and conceptual potential of shell gold in miniature painting, using it not just for decoration but as an integral part of the composition, enhancing the sense of realism and preciousness. His technical mastery set a high standard for miniature painting in Northern Europe.

Illuminating Manuscripts: The Mira Calligraphiae Monumenta

Perhaps Hoefnagel's most celebrated work is his contribution to the Mira Calligraphiae Monumenta (The Model Book of Calligraphy). This manuscript, originally created between 1561 and 1562 by the imperial secretary Georg Bocskay for Emperor Ferdinand I, was a showcase of diverse calligraphic scripts. Decades later, between 1591 and 1596, Emperor Rudolf II commissioned Hoefnagel to add illuminations to Bocskay's existing pages. This unusual collaboration, separated by thirty years, resulted in a masterpiece of late Renaissance book art, now housed in the J. Paul Getty Museum.

Hoefnagel's task was to embellish Bocskay's masterful calligraphy without overwhelming it. He achieved this brilliantly, adding exquisite borders and vignettes filled with hyper-realistic depictions of flowers, fruits, insects, small animals, shells, and even everyday objects. His illustrations interact playfully with the script, sometimes seeming to crawl across the page or cast shadows upon it. He employed trompe-l'œil (trick-the-eye) effects with remarkable skill, painting illusionistic tears in the parchment, seemingly scattered petals, or insects that appear startlingly real, demonstrating both his technical virtuosity and his wit.

The Mira Calligraphiae Monumenta showcases Hoefnagel's profound understanding of nature, his mastery of miniature painting, and his ability to integrate complex imagery within a pre-existing framework. The subjects often carry symbolic weight, alluding to themes of life, death, resurrection, and the passage of time, adding intellectual depth to the visual splendor. The work stands as a unique dialogue between two masters of their respective crafts, separated by time but united by imperial patronage.

Service to Princes: Patronage in Munich and Prague

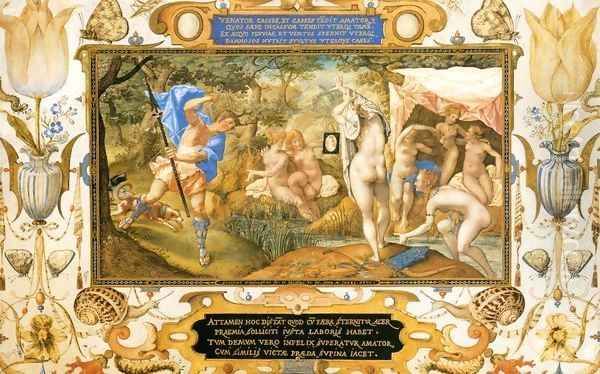

Like many artists of his era, Hoefnagel relied on elite patronage. His skills attracted the attention of powerful rulers who valued his unique blend of artistic talent and intellectual depth. His earliest significant patron was Duke Albert V of Bavaria, for whom he worked in Munich. For Albert, Hoefnagel created allegorical works, including the Allegory on the Reign of Duke Albert V of Bavaria, a complex miniature celebrating the Duke's virtues and accomplishments through symbolic imagery, including references to strength (Hercules) and the arts.

His most important patron, however, was the Holy Roman Emperor Rudolf II. In 1591, facing religious pressures in Vienna, Hoefnagel moved to Prague to join Rudolf's celebrated court. Rudolf II was an avid collector of art and curiosities, deeply interested in alchemy, astrology, and the natural sciences. His court attracted artists and intellectuals from across Europe, creating a unique cultural milieu. Hoefnagel's meticulous naturalism, combined with his penchant for symbolism and allegory, resonated perfectly with the Emperor's tastes. It was during his service to Rudolf that he completed the illuminations for the Mira Calligraphiae Monumenta and likely produced other exquisite miniatures and natural history studies.

Hoefnagel became a key figure within the Rudolphine school of artists, known for its sophisticated Mannerist style, intellectual complexity, and fascination with the exotic and the erotic. He worked alongside other prominent court artists such as the painters Bartholomäus Spranger, Hans von Aachen, the nature painter Roelandt Savery, and the creator of fantastical composite heads, Giuseppe Arcimboldo. Hoefnagel's contribution was distinct, focusing on the miniature and the natural world, but sharing the court's emphasis on refinement, intricate detail, and hidden meanings.

Topography and the Wider World: Civitates Orbis Terrarum

Hoefnagel's talents extended to topographical drawing and cartography, reflecting the era's burgeoning interest in accurately mapping the known world. His travels provided him with ample opportunity to sketch city views, landscapes, and architectural details. These skills found a significant outlet in his contributions to the Civitates Orbis Terrarum (Cities of the World), one of the most ambitious atlas projects of the late 16th century.

Published in Cologne between 1572 and 1617 by Georg Braun (theologian and editor) and primarily engraved by Frans Hogenberg, the Civitates comprised six volumes containing hundreds of bird's-eye views and maps of cities from across Europe, Africa, Asia, and even the Americas. Hoefnagel was a major contributor of original drawings for the atlas, based on his own travels or sourced from other artists. His detailed and accurate views provided invaluable visual information about urban centers at the time, capturing not only their layout but also aspects of daily life, costume, and local landmarks. His contributions significantly enhanced the scope and quality of this landmark publication, which remained influential for centuries.

The Printed Legacy: Archetypa Studiaque and Influence

While Hoefnagel is renowned for his unique manuscript illuminations and miniatures, his influence also spread through print. In 1592, a series of engravings based on his nature studies was published in Frankfurt under the title Archetypa studiaque patris Georgii Hoefnagelii. The engravings were executed by his talented son, Jacob Hoefnagel (1573–c. 1632), who followed in his father's footsteps as an artist, also serving the Rudolphine court.

The Archetypa (often referred to as the Microcosmos) consisted of plates featuring meticulously arranged compositions of flowers, insects, fruits, and small animals, often accompanied by Latin mottoes or emblems. These prints made Hoefnagel's detailed natural observations accessible to a much wider audience of artists and collectors. They served as important source material and inspiration for the development of still life painting in the Netherlands and Germany in the early 17th century. Artists like Roelandt Savery, Ambrosius Bosschaert the Elder, Jan Brueghel the Elder, and later specialists in insect painting like Jan van Kessel the Elder, clearly drew upon Hoefnagel's models, adopting his precision, compositional arrangements, and sometimes his symbolic undertones. The Archetypa cemented Hoefnagel's reputation as a foundational figure in the Northern European tradition of detailed nature painting.

Style, Symbolism, and Artistic Identity

Joris Hoefnagel's artistic style is characterized by a remarkable synthesis of meticulous naturalism and complex symbolism. His commitment to empirical observation, possibly influenced by precursors like Albrecht Dürer in his nature studies, resulted in depictions of flora and fauna rendered with almost photographic accuracy. Yet, these elements were rarely presented merely as specimens; they were woven into intricate compositions imbued with allegorical, moral, or religious meaning, reflecting his humanist background and the intellectual climate of the Rudolphine court.

He masterfully employed techniques like trompe-l'œil to blur the line between the painted illusion and reality, adding a layer of playful sophistication to his work. His compositions, particularly in the Archetypa and Mira, often feature a sense of deliberate arrangement, sometimes symmetrical, sometimes seemingly random, but always carefully balanced. His use of vibrant color and delicate handling of light, especially in his miniatures, gives his work a luminous quality. He even developed a distinctive personal emblem or signature, sometimes incorporating a visual pun on his name (a nail, 'Nagel' in German/Dutch, being struck by a hammer), asserting his artistic identity.

His influence was profound, particularly on the development of Flemish and Dutch still life painting. He helped establish flowers, insects, and shells as worthy subjects for independent artworks, moving beyond their traditional role in manuscript borders or religious symbolism. His detailed, objective approach laid groundwork for both scientific illustration and the highly refined still life genres that flourished in the Dutch Golden Age, influencing generations of artists who specialized in capturing the beauty and transience of the natural world.

Legacy and Collections

Joris Hoefnagel died in Vienna in 1601 (though some sources cite 1600), leaving behind a rich and diverse body of work. His unique position straddling late manuscript illumination, Renaissance naturalism, Mannerist complexity, and the burgeoning genres of still life and topographical art makes him a pivotal figure in art history. He successfully navigated the transition from the medieval workshop tradition to the more independent, intellectually driven artistic practices of the early modern period. His ability to blend meticulous craft with profound intellectual content ensured his appeal to the most discerning patrons of his time.

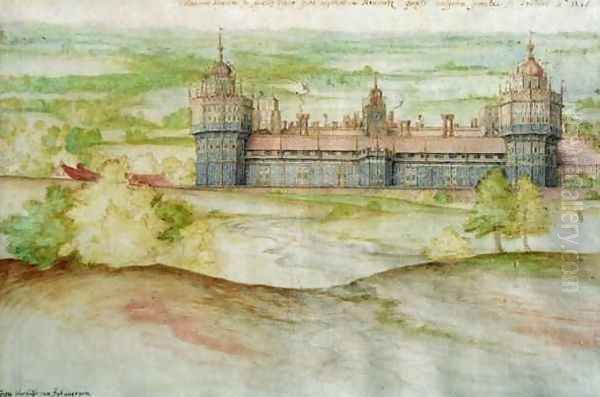

Today, Hoefnagel's works are held in major museums and collections worldwide. Significant holdings can be found at the National Gallery of Art in Washington, D.C. (notably The Four Elements), the J. Paul Getty Museum in Los Angeles (Mira Calligraphiae Monumenta), the Victoria and Albert Museum in London (topographical views like Nonsuch Palace), the Staatliche Museen zu Berlin (allegorical miniatures), the Rijksmuseum in Amsterdam (Two Mice), and the Museum Plantin-Moretus in Antwerp.

His importance has been recognized through dedicated exhibitions, such as "Art and Science: Joris Hoefnagel and the Representation of Nature in the Renaissance" at the Getty Museum in 2000, and focused displays at institutions like the National Gallery of Art. These exhibitions highlight his dual role as both a masterful artist and a keen observer of the natural world, showcasing his enduring relevance to the histories of both art and science.

Conclusion: A Singular Vision

Joris Hoefnagel remains a fascinating and somewhat enigmatic figure, a true polymath whose career intersected with major artistic, scientific, and political currents of the late 16th century. From the mercantile wealth of Antwerp to the sophisticated courts of Munich and Prague, he adapted and thrived, producing works of extraordinary beauty and precision. His meticulous depictions of nature laid the groundwork for future developments in still life and scientific illustration, while his contributions to manuscript illumination represent a final, brilliant flourishing of that ancient art form. As an artist, naturalist, miniaturist, cartographer, and traveler, Hoefnagel forged a singular path, leaving behind a legacy that continues to captivate with its intricate detail, intellectual depth, and sheer visual delight. He stands as a testament to the boundless curiosity and creative energy of the Renaissance mind.