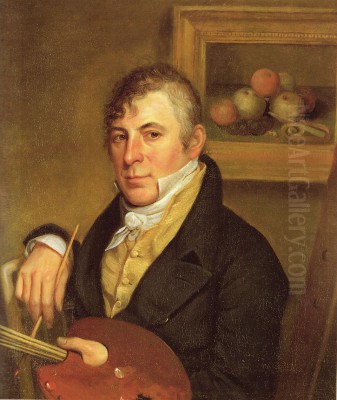

Raphaelle Peale, born in 1774 and passing in 1825, stands as a seminal figure in the nascent American art scene, particularly distinguished as arguably the first professional American painter to dedicate a significant portion of his career to the genre of still life. As the eldest son of the renowned artist, naturalist, and museum proprietor Charles Willson Peale, Raphaelle was immersed in a world of art and science from his earliest days. Despite a life marked by personal tragedy, chronic illness, and financial instability, his artistic output, especially his still life compositions, reveals a profound sensitivity, meticulous technique, and a quiet intensity that has earned him lasting recognition. His work offers a unique window into the aesthetic sensibilities and cultural undercurrents of the early American Republic.

Early Life and Artistic Progeny

Born in Annapolis, Maryland, Raphaelle Peale was the first surviving child of Charles Willson Peale and his first wife, Rachel Brewer. The Peale household was an extraordinary environment, a veritable crucible of artistic and scientific endeavor. Charles Willson Peale, a towering figure of the American Enlightenment, not only painted portraits of revolutionary heroes but also established one of America's first public museums in Philadelphia. He named his children after famous artists and scientists – Raphaelle, Rembrandt, Rubens, Titian Ramsay, Angelica Kauffman, and Sophonisba Angusciola – clearly signaling his ambitions for their future.

Raphaelle received his primary artistic instruction directly from his father, a versatile artist proficient in portraiture, miniatures, and even landscape. He would have also been exposed to the work of his uncle, James Peale, himself a skilled miniaturist and still life painter. The Peale family operated almost as an artistic guild, with various members contributing to different aspects of the family's artistic and museum enterprises. This early immersion provided Raphaelle with a solid technical foundation, though his artistic temperament would eventually lead him down a path distinct from his father's more public-facing and historically-oriented ambitions.

From a young age, Raphaelle assisted his father in the Peale Museum. This involved not only artistic tasks like painting backgrounds for exhibits or restoring artworks but also more scientific pursuits such as taxidermy and specimen preparation. This hands-on experience with the natural world, the close observation of textures, forms, and the effects of light on various objects, undoubtedly informed his later precision in still life painting. However, this work also exposed him to hazardous materials, including arsenic and mercury used in preserving specimens, which many scholars believe contributed to his lifelong health problems.

Early Career: Portraits and Ventures

Initially, Raphaelle Peale followed the more conventional and commercially viable path of portraiture, a genre in which his father had achieved considerable success. By 1794, Charles Willson Peale, seeking to focus more on his museum, announced that he was largely entrusting his portraiture business to his sons Raphaelle and Rembrandt. Raphaelle's early portraits demonstrate a competent hand, capturing likenesses with a degree of sensitivity. He exhibited for the first time in 1794 at the Columbianum, an early American art academy in Philadelphia, showing five portraits and other works.

In 1797, Raphaelle, alongside his younger and often more commercially successful brother Rembrandt Peale, embarked on an ambitious but ultimately ill-fated venture. They traveled to Charleston, South Carolina, with the intention of establishing a museum modeled after their father's Philadelphia institution. The endeavor did not flourish, and the brothers soon returned north. This period also saw Raphaelle working as an itinerant artist, traveling to cities like Baltimore to seek portrait commissions. He also practiced the delicate art of miniature painting, a popular form at the time, though his failing eyesight and unsteady hands, exacerbated by his declining health, would later force him to largely abandon this intricate work.

Despite these efforts, Raphaelle struggled to achieve consistent financial success or the level of public acclaim enjoyed by contemporaries like Gilbert Stuart or even his own brother Rembrandt. His temperament, perhaps less suited to the social demands of portraiture, combined with his burgeoning health issues, likely contributed to these professional challenges.

The Pivotal Turn to Still Life

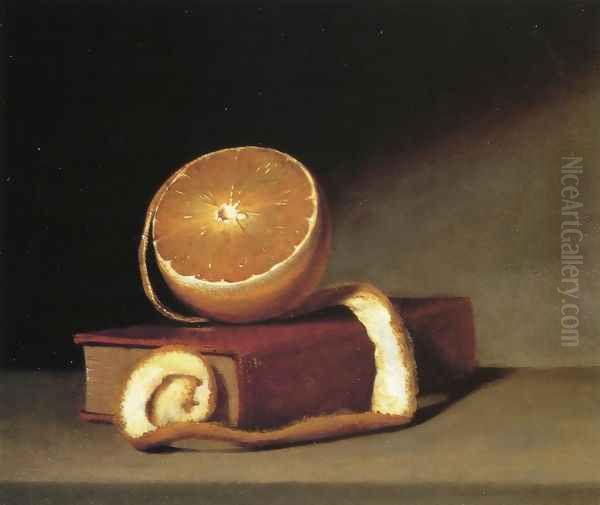

Around 1810, and more definitively from 1815 onwards, Raphaelle Peale began to concentrate on still life painting. This was a significant departure in the context of early American art, where portraiture and historical scenes, championed by artists like Benjamin West and John Trumbull, held the highest prestige. Still life was often considered a lesser genre, more decorative than intellectually profound. However, for Raphaelle, it became a primary mode of artistic expression.

His decision may have been partly pragmatic. Still lifes could be composed and painted in the studio, requiring less interaction with patrons and accommodating his fluctuating health. But more importantly, the genre seems to have resonated deeply with his artistic sensibilities. He approached his subjects – typically arrangements of fruit, vegetables, and tableware – with an intense focus and a desire for verisimilitude that bordered on the scientific.

Raphaelle Peale’s still lifes are characterized by their balanced, often symmetrical compositions, a muted palette, and an extraordinary attention to detail. He rendered the textures of a peach's fuzz, the sheen on a grape, the crumbly surface of a cake, or the cool gleam of porcelain with remarkable fidelity. Unlike the opulent and often symbolic still lifes of the Dutch Golden Age masters such as Willem Claesz. Heda or Pieter Claesz, whose works he may have known through prints or the occasional imported painting, Raphaelle’s compositions are generally simpler and more restrained, imbued with a distinctly American directness and a quiet, almost melancholic, dignity.

His works often feature a shallow space, with objects arranged on a simple wooden ledge or tabletop against a dark, neutral background. This focuses the viewer's attention entirely on the objects themselves, their forms, colors, and interrelationships. The lighting is typically subtle, creating soft gradations of tone and highlighting the tactile qualities of the depicted items. There is a palpable sense of stillness and contemplation in these works, a feeling that time has been momentarily suspended.

Masterworks of Quiet Observation

Among Raphaelle Peale’s most celebrated still lifes is Still Life with Strawberries, Nuts, &c. (1822, Art Institute of Chicago). This painting exemplifies his mature style. A small, overflowing basket of strawberries, a few scattered nuts, raisins, and a sponge cake are meticulously arranged on a dark surface. Each element is rendered with exquisite precision, from the delicate seeds of the strawberries to the varied textures of the nuts and the airy lightness of the cake. The composition is deceptively simple, yet it achieves a harmonious balance and a profound sense of presence.

Another notable work, A Dessert (also known as Still Life with Blackberries, c. 1814, National Gallery of Art, Washington D.C.), showcases his skill in depicting different textures and the subtle interplay of light. A bowl of blackberries, a wine glass, a decanter, and pieces of fruit are arranged with an understated elegance. The reflections in the glass and the decanter are particularly well-handled, demonstrating his keen observational powers.

His fruit pieces, such as Melons and Morning Glories (c. 1813, Smithsonian American Art Museum), often carry a subtle vanitas theme, common in still life traditions. The ripe, luscious fruit, juxtaposed with the delicate and ephemeral morning glory flowers, can be seen as a meditation on the transience of life and beauty. The cut watermelon reveals its vibrant red flesh and dark seeds, a feast for the eyes, yet one that will not last.

While fruit and food were his most common subjects, he also painted other items. Still Life with Cake (1818, Metropolitan Museum of Art) is another fine example of his ability to capture the essence of everyday objects, transforming them into subjects of serious artistic contemplation. The simplicity of the arrangement – a slice of cake, a glass of wine, and a few raisins – belies the skill involved in its execution.

Trompe l’oeil and Artistic Wit

Raphaelle Peale, like other members of his family, was intrigued by illusionism and the artistic game of trompe l’oeil (“to deceive the eye”). His father, Charles Willson Peale, had famously created The Staircase Group (1795), a double portrait of his sons Raphaelle and Titian Ramsay Peale ascending a staircase, which was so realistic that George Washington is said to have bowed to the painted figures.

Raphaelle created his own notable trompe l’oeil works, the most famous being Venus Rising from the Sea—A Deception (also known as After Peale's Bath or Catalogue Deception, c. 1822, Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art). This painting depicts a white linen cloth or napkin tacked to a darker background, seemingly covering another painting beneath it. Only a tantalizing glimpse of a woman’s arm and foot, and a lock of hair, are visible, hinting at a classical subject like the birth of Venus. The illusion of the cloth is masterfully rendered, complete with folds, shadows, and the depiction of the tacks holding it in place.

The work is a witty commentary on artistic conventions, modesty, and the act of viewing. It teases the audience, playing with their expectations and curiosity. Some scholars have interpreted it as a humorous response to the prudishness of Philadelphia society or perhaps even a playful jab at the more idealized, classical subjects favored by academic traditions, which were less common in the pragmatic American art scene of the time. This painting reveals a sophisticated, intellectual humor that adds another dimension to Raphaelle’s artistic personality.

Influences and Artistic Milieu

Raphaelle Peale’s art did not develop in a vacuum. The influence of 17th-century Dutch and Flemish still life painters is evident in his choice of subject matter and his meticulous realism. Artists like Willem Kalf, Rachel Ruysch, and Jan van Huysum had established a rich tradition of still life painting that emphasized detailed observation and often carried symbolic meanings. While direct exposure to many such original works would have been limited in early America, prints and copies circulated, and some collections, like that of Robert Gilmor Jr. in Baltimore, contained European examples.

Closer to home, his father Charles Willson Peale and his uncle James Peale both painted still lifes. James Peale, in particular, produced a significant body of still life work, often richer in color and more abundant in composition than Raphaelle’s more austere arrangements. There was likely a degree of mutual influence and perhaps even friendly rivalry between uncle and nephew in this genre.

Within the broader American art scene, Raphaelle’s dedication to still life set him apart. While prominent artists like Thomas Sully, a contemporary in Philadelphia, focused on elegant portraiture, and history painters like Washington Allston (though spending much time abroad) aimed for grand narratives, Raphaelle found his voice in the quiet dignity of everyday objects. His commitment to this genre helped to legitimize it in America, paving the way for later 19th-century still life specialists such as John F. Francis and Severin Roesen, who would develop the tradition in more opulent and varied directions.

Personal Struggles and Declining Health

Raphaelle Peale’s artistic achievements are all the more remarkable given the considerable personal hardships he endured. In 1797, he married Martha (Patty) McGlathery, and together they had eight children. However, their domestic life was often fraught with difficulty, largely due to Raphaelle’s chronic ill health and his struggles with alcoholism. His income from painting was erratic, leading to persistent financial insecurity for the family. Martha was often left to manage the household and raise the children under challenging circumstances.

His health problems were severe and multifaceted. He suffered from gout, a painful condition that afflicted his hands and feet, making the delicate work of painting increasingly difficult. He also experienced episodes of delirium and severe internal pains. As mentioned earlier, it is widely believed that these ailments were exacerbated, if not caused, by poisoning from arsenic and mercury, substances he handled regularly while working as a taxidermist in his father's museum.

His alcoholism was a source of great distress to himself and his family. Charles Willson Peale, a man of discipline and strong moral convictions, repeatedly admonished his son in letters, urging him to abstain from alcohol and to take better care of his health and responsibilities. These letters reveal a father’s deep concern and frustration, but Raphaelle seemed unable to overcome his addiction. The combination of physical illness and alcoholism created a vicious cycle, further undermining his ability to work consistently and support his family.

Later Years and Untimely Death

Despite his debilitating health, Raphaelle Peale continued to paint and exhibit his still lifes throughout the 1810s and early 1820s. He regularly sent his works to the annual exhibitions at the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts (PAFA), an institution his father had helped to found. While his still lifes were generally well-received critically for their technical skill, they did not command high prices or bring him widespread fame during his lifetime. The prevailing taste still favored portraiture and grander subjects.

His physical condition continued to deteriorate. In his final years, he was often bedridden or confined to his home. The precise circumstances of his death in March 1825, at the age of just 51, are somewhat obscure, but it is generally attributed to the cumulative effects of his chronic illnesses and alcoholism. He died in Philadelphia, leaving behind a legacy of exquisitely crafted paintings that were, for a time, largely overlooked.

Legacy and Reassessment

For many decades after his death, Raphaelle Peale remained a relatively obscure figure, overshadowed by his more famous father and brother Rembrandt. His still lifes, though appreciated by a few connoisseurs, did not fit neatly into the grand narratives of American art history that were being constructed in the later 19th and early 20th centuries.

However, a gradual reassessment began in the mid-20th century, spurred by a growing scholarly interest in American still life painting and a deeper appreciation for the subtleties of his work. Curators and art historians began to recognize the unique quality of his vision – the quiet intensity, the psychological depth, and the sheer technical brilliance of his paintings. Exhibitions dedicated to the Peale family and to American still life brought his work to a wider audience.

Today, Raphaelle Peale is widely regarded as a master of American still life and a key figure in the early development of American art. His paintings are prized for their refined aesthetics, their meticulous realism, and the introspective mood they evoke. They are seen not merely as skillful depictions of objects, but as profound meditations on perception, materiality, and the quiet beauty of the everyday. His ability to imbue simple subjects with such presence and significance is a testament to his unique artistic genius. His works are now held in major American museums, recognized as foundational contributions to the nation's artistic heritage. He stands as a poignant example of an artist whose true stature was only fully appreciated long after his troubled life had ended.

Conclusion

Raphaelle Peale’s life was a complex tapestry of artistic brilliance, familial expectation, personal suffering, and quiet perseverance. Born into America’s most prominent artistic dynasty, he forged a distinctive path, dedicating himself to the then-underappreciated genre of still life. His works, characterized by their meticulous detail, subtle beauty, and often-poignant stillness, transcend mere representation. They invite contemplation and reveal an artist of profound sensitivity and skill. Despite the adversities he faced – chronic illness, addiction, and limited contemporary recognition – Raphaelle Peale created a body of work that has secured his place as a pioneer of American still life painting, an artist whose quiet masterpieces continue to resonate with viewers today, offering a timeless glimpse into the fragile beauty of the world he so carefully observed.