Charles Laborde, often signing his work as Chas Laborde, stands as a significant, if sometimes overlooked, figure in early 20th-century French art. Born on August 8, 1886, in Buenos Aires, Argentina, to French parents, he would become a quintessential Parisian artist, capturing the vibrant, often tumultuous, spirit of his times. His multifaceted career encompassed roles as a writer, journalist, engraver, painter, and, most notably, an illustrator whose keen eye and deft hand documented the social fabric of Paris, London, and Berlin. Laborde's life and work were intrinsically linked to the shifting cultural landscapes of the pre and post-World War I era, culminating in his untimely death in Paris in 1941 during the German occupation.

Early Life and Artistic Formation

Though born in the Argentine capital, Charles Laborde's formative years were spent in the Pyrenees region of France, where his family relocated. This upbringing perhaps instilled in him a sense of observation that would later define his artistic output. Drawn to the magnetic pull of Paris, the undisputed center of the art world at the turn of the century, Laborde arrived in the city around 1903, at the tender age of seventeen, eager to immerse himself in its creative ferment.

His formal artistic education was somewhat characteristic of many independent-minded artists of his generation. He enrolled at the prestigious Académie Julian, a private art school known for its less rigid approach compared to the official École des Beaux-Arts. He also spent time at the École des Beaux-Arts itself, but his temperament chafed under the constraints of academicism. Laborde found the traditional curriculum uninspiring and soon abandoned formal studies, preferring to forge his own path. This independent streak would become a hallmark of his career, as he sought to capture life directly, rather than through the filter of academic convention.

His early foray into the professional art world was through illustration. Paris at this time boasted a plethora of newspapers, satirical journals, and literary magazines, all hungry for visual content. Laborde quickly found work contributing drawings and caricatures, honing his skills in draftsmanship and developing his ability to encapsulate a character or a scene with a few telling strokes. This early journalistic work provided him with both a livelihood and an invaluable training ground, forcing him to observe acutely and work efficiently.

The Illustrator of Modern Life

Charles Laborde truly came into his own as an illustrator, becoming a perceptive and often satirical chronicler of urban existence in the 1910s, 1920s, and 1930s. His work provides a vivid panorama of the "Roaring Twenties" and the interwar period, capturing its exuberance, its anxieties, and its evolving social mores. He was particularly drawn to the bustling life of great metropolises, with Paris, London, and Berlin serving as his primary muses.

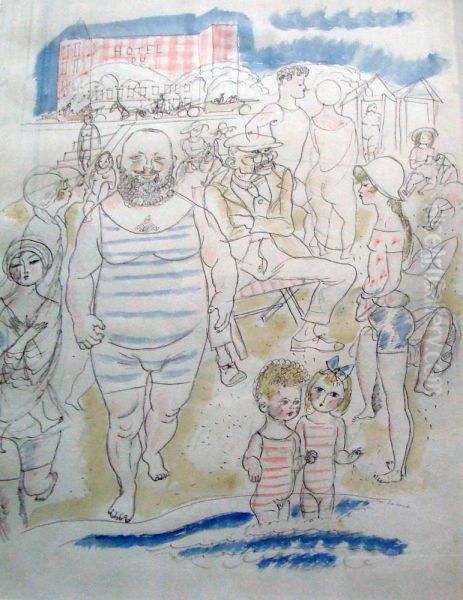

His style was characterized by a fluid, elegant line, often infused with a subtle wit or a darker, more incisive humor. He possessed a remarkable ability to convey the atmosphere of a place – the crowded cafes, the fashionable boulevards, the shadowy backstreets, the theaters, and the racecourses. His figures, though often stylized, are imbued with life and personality, reflecting the diverse cast of characters that populated the modern city: flappers, dandies, businessmen, workers, artists, and the denizens of the demimonde.

Laborde's illustrations frequently appeared in prominent publications of the day, including the sophisticated fashion journal La Gazette du bon ton, where his work appeared alongside that of other notable illustrators like George Barbier, Georges Lepape, and André Édouard Marty. He also contributed to satirical magazines such as Le Rire and La Vie Parisienne, platforms that allowed him to exercise his critical eye on contemporary society. His work for these publications was not merely decorative; it often carried a layer of social commentary, subtly critiquing the follies and pretensions he observed.

Key Themes and Subjects

A recurring theme in Laborde's oeuvre is the dynamism of urban life. He was fascinated by the spectacle of the city, its constant movement, its fleeting encounters, and its stark contrasts. His depictions of Parisian life are particularly noteworthy, capturing the unique charm and energy of the French capital. From the elegant throngs on the Champs-Élysées to the more intimate scenes in Montmartre cafes, Laborde painted a rich tapestry of Parisian society.

His travels to London and Berlin further broadened his thematic scope. His observations of London life, often focusing on its street scenes, its distinct social types, and its particular urban rhythm, offer a fascinating counterpoint to his Parisian work. In Berlin, particularly during the Weimar Republic era, Laborde found a city pulsating with creative energy but also fraught with social and political tensions. His Berlin scenes often possess a sharper, more critical edge, akin to the work of German artists like George Grosz or Otto Dix, though Laborde's style remained distinctly French in its elegance and restraint.

Beyond the urban spectacle, Laborde was also a skilled renderer of the human form, particularly nudes. These works, often executed with a delicate sensuality, showcase his mastery of line and his appreciation for classical form, even as they are filtered through a modern sensibility. His nudes are not idealized goddesses but rather contemporary women, depicted with an honesty and directness that was characteristic of his approach.

Fashion was another important subject for Laborde, not merely as a chronicler of trends but as an observer of how clothing shaped identity and social interaction. His figures are invariably well-dressed, their attire meticulously rendered, providing valuable insights into the sartorial codes of the period. This interest aligned him with other great illustrators of the Art Deco era who saw fashion as an integral part of modern visual culture.

Notable Works and Series

Among Charles Laborde's most celebrated works are his illustrated books and portfolios, which allowed him to develop his themes and narratives more extensively. One of his most significant achievements is the series Rues et Visages de Berlin (Streets and Faces of Berlin), published in 1930. This collection of etchings and drypoints offers a compelling and atmospheric portrait of the German capital in the late 1920s. Laborde captures the city's vibrant nightlife, its diverse populace, and the underlying sense of unease that characterized the Weimar period. The work is a masterful example of his ability to combine topographical accuracy with a strong sense of mood and character.

Another key work is Sentimental Inflation, an illustrated book that reflects on the disillusionment and economic instability of the post-World War I era. This work, imbued with a poignant, melancholic humor, showcases Laborde's capacity for social satire and his empathy for the human condition in times of hardship. It is considered one of his most personal and expressive creations.

He also illustrated numerous literary works, bringing his distinctive visual style to the texts of contemporary authors. His illustrations for Colette's L'Ingénue Libertine and Francis Carco's Rien qu'un Femme are notable examples. In these projects, Laborde demonstrated a remarkable ability to complement and enhance the literary narrative, creating a harmonious interplay between text and image.

His individual prints, such as La Grande Fête and Au Bain, often executed in black ink with watercolor washes, further highlight his skill in capturing fleeting moments of daily life with spontaneity and charm. These works, while perhaps less ambitious in scope than his larger series, are nonetheless testament to his consistent artistic vision and technical proficiency. The influence of earlier masters of social observation and caricature, such as Honoré Daumier and Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec, can be discerned in his approach, yet Laborde forged a style uniquely his own.

Technique and Mediums

Charles Laborde was a versatile artist, proficient in various mediums, but he excelled particularly in drawing and printmaking. Etching and drypoint were his favored techniques for his series and book illustrations, allowing him to achieve the fine, expressive lines that are a hallmark of his style. His mastery of these intaglio processes enabled him to create rich tonal variations and intricate details, lending depth and texture to his urban scenes and character studies.

His drawings, often executed in pen and ink, sometimes with the addition of watercolor or gouache, display a remarkable fluidity and economy of means. He could suggest form, movement, and atmosphere with a seemingly effortless grace. This facility with line was undoubtedly honed during his early years as a newspaper illustrator, where speed and clarity were paramount.

Laborde's use of color was typically subtle and sophisticated. In his hand-colored prints and watercolor drawings, he employed a palette that was both descriptive and evocative, enhancing the mood of the scene without overpowering the underlying draftsmanship. His color choices often reflect the fashionable aesthetics of the Art Deco period, with its preference for elegant and sometimes unexpected harmonies. He shared this sensibility with contemporaries like Raoul Dufy, whose own work often blended decorative appeal with keen observation.

The Parisian Art Scene and Contemporaries

Charles Laborde operated within a vibrant and diverse Parisian art scene. While not aligning himself with any single avant-garde movement like Cubism or Surrealism, his work was undeniably modern in its subject matter and its embrace of new modes of visual communication. He was part of a generation of artists who recognized the power of illustration and graphic arts to reach a wide audience and to comment on contemporary life.

His circle would have included other illustrators, writers, and figures from the worlds of fashion and publishing. Artists like Pascin (Jules Pascin), known for his sensuous depictions of Parisian bohemia, shared Laborde's interest in capturing the human element of the city. The aforementioned illustrators of La Gazette du bon ton – Barbier, Lepape, Marty, as well as Bernard Boutet de Monvel with his precise, dandyish figures, and Jean-Gabriel Domergue, painter of the "Parisienne" – formed a constellation of talents who defined the visual style of the era.

The influence of earlier artists who had made the city their subject, such as Théophile Steinlen with his compassionate portrayals of working-class Paris, or Jean-Louis Forain, whose incisive drawings satirized the legal and theatrical worlds, also provided a rich heritage upon which Laborde could draw. Even the spirit of Kees van Dongen, a Fauvist who later became a celebrated society portraitist, resonated with Laborde's engagement with the fashionable echelons of society. The caricaturist Sem (Georges Goursat), with his witty and instantly recognizable depictions of Parisian celebrities, was another contemporary whose work shared Laborde's focus on social observation.

Laborde's engagement with Berlin also placed him in a dialogue, however indirect, with the powerful currents of German Expressionism and Neue Sachlichkeit (New Objectivity). While his style remained more rooted in French traditions of elegance and wit, his Berlin works acknowledge the city's unique and often starker realities, as depicted by artists like Grosz and Dix.

Legacy and Recognition

Charles Laborde's career was tragically cut short by his death in 1941, at the age of 55, during the dark years of the Nazi occupation of Paris. This premature end, coupled with the dramatic rupture of World War II, perhaps contributed to his work being somewhat less widely known in the post-war era compared to some of his contemporaries who survived and continued to produce.

Nevertheless, his contribution to the art of illustration and his role as a visual historian of his time are undeniable. His works remain highly sought after by collectors and are valued for their artistic quality, their historical significance, and their evocative portrayal of a bygone era. Museums and galleries, particularly in France, hold examples of his prints and drawings, recognizing their importance in the narrative of early 20th-century art.

Laborde's legacy lies in his ability to capture the ephemeral "spirit of the age" – the Zeitgeist – with acuity, elegance, and often a touch of irony. He was more than just a recorder of scenes; he was an interpreter of social dynamics, a subtle critic, and an artist who found beauty and meaning in the everyday spectacle of modern urban life. His illustrations offer a window into the world of the 1920s and 30s, a world of glamour and anxiety, of tradition and modernity, all rendered with a distinctive and sophisticated artistic voice.

His dedication to his craft, his independent spirit, and his keen observational skills place him firmly within the tradition of great French illustrators and social commentators. While he may not have sought the revolutionary paths of the major avant-garde movements, his focused and insightful depictions of his own time provide an invaluable and aesthetically rich record that continues to resonate with viewers today.

Conclusion

Charles Laborde was an artist deeply attuned to the nuances of his environment. From the bustling streets of Paris to the complex social fabric of Berlin and London, he translated his observations into a body of work that is both a delightful visual record and a subtle commentary on the human condition in the modern age. His mastery of line, his sophisticated use of color, and his ability to infuse his scenes with atmosphere and character distinguish him as a significant talent. As a writer, engraver, painter, and above all, an illustrator, Chas Laborde left behind a legacy that continues to inform and enchant, offering a unique and personal perspective on a pivotal period in European history and art. His work serves as a poignant reminder of the power of art to capture the fleeting moments that define an era.