Gerard Soest, also known by the anglicized Gerald Soest, stands as a notable figure in the landscape of 17th-century English portraiture. Born around 1600, likely in the Netherlands, and passing away in London in February 1681, Soest carved a distinct niche for himself during a vibrant and transformative period in British art. Though not reaching the towering fame of some of his contemporaries, his work offers a fascinating glimpse into the artistic tastes and societal structures of Restoration England, characterized by a robust realism and a departure from the more flamboyant courtly styles.

Origins and Arrival in England

The precise birthplace of Gerard Soest remains a subject of some discussion among art historians. While traditionally considered Dutch, with Soest in Utrecht or Westphalia (then part of the Holy Roman Empire, with towns like Soest) being plausible origins, the prevailing consensus points towards a Dutch background. He is believed to have received his artistic training in the Netherlands, an environment teeming with artistic innovation during its Golden Age. Masters like Rembrandt van Rijn, Frans Hals, and Johannes Vermeer were revolutionizing portraiture, genre scenes, and landscape painting, instilling a deep appreciation for verisimilitude, psychological depth, and the masterful handling of light and texture.

Soest is thought to have arrived in England in the mid-1640s, possibly around 1644 or 1646. This was a tumultuous period in English history, with the Civil War (1642-1651) raging. The art market, particularly for luxury items like portraits, was undoubtedly affected. The patronage of King Charles I, a renowned connoisseur, had been disrupted, and his court painter, Anthony van Dyck, had died in 1641, leaving a significant void. Despite the unrest, London remained a center of commerce and culture, and there was still a demand for portraiture among the gentry and emerging merchant classes.

Artistic Style: Dutch Realism Meets English Sensibilities

Gerard Soest’s artistic style is firmly rooted in the Dutch tradition of realism. He possessed a keen eye for detail, rendering fabrics, facial features, and accessories with meticulous care. His approach was generally more direct and less idealized than that of some of his contemporaries who catered to the aristocratic desire for flattering portrayals. This unvarnished quality gives his portraits a sense of authenticity and character.

A significant influence on Soest's work, particularly in his English period, is believed to be William Dobson (1611-1646). Dobson, often considered one of the finest English-born painters before Hogarth, had developed a robust, somewhat melancholic style of portraiture that captured the gravity of the Civil War era. Soest’s portraits share some of Dobson’s solidity and directness, though perhaps with a slightly cooler Netherlandish palette at times.

Soest's technique often involved the application of paint in relatively thin layers, allowing for subtle gradations of tone and a smooth finish. He was particularly adept at capturing the textures of satin, lace, and armor. His depiction of hands is often noted for its elegance and accuracy, a hallmark of a skilled portraitist. While his compositions are generally straightforward, focusing on the sitter, he occasionally incorporated symbolic elements or background details that added depth to the portrayal.

Compared to Sir Peter Lely (1618-1680), who became the dominant portrait painter in England after the Restoration of the monarchy in 1660, Soest’s style was more austere. Lely, also of Dutch origin, adopted a more flamboyant, continental Baroque manner, heavily influenced by Van Dyck, which proved immensely popular with the restored court of Charles II. Lely’s portraits often featured languid poses, rich colors, and an air of aristocratic nonchalance. Soest, in contrast, maintained a more sober and direct approach, which perhaps limited his appeal to the highest echelons of courtly society but found favor with a clientele that appreciated his unpretentious realism.

Notable Sitters and Key Portraits

Gerard Soest’s oeuvre consists primarily of portraits of English gentry, intellectuals, and members of prominent families. While he never secured official royal commissions, his client base was respectable and provided him with a steady stream of work.

One of his most frequently discussed works is the Portrait of William Shakespeare. This painting, believed to have been created between 1660 and 1680, is a posthumous portrait. It is thought to be based on earlier likenesses, most notably the "Chandos" portrait, which is attributed by some to John Taylor and is one of the few portraits with a claim to have been painted from life. Soest’s interpretation presents a thoughtful, slightly melancholic Shakespeare, rendered with the artist's characteristic attention to facial structure and expression. An early version of a Shakespeare portrait by Soest, dated by some scholars to as early as 1646, was in the collection of Thomas Wright by 1725 and was engraved by John Simon, which helped to disseminate this particular image of the Bard. The existence of multiple versions and copies speaks to the enduring fascination with Shakespeare's likeness.

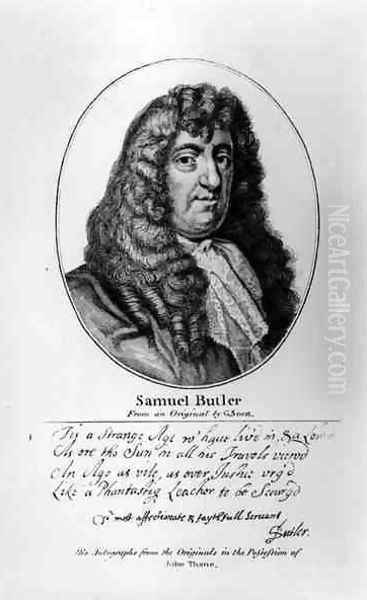

Another significant sitter was Samuel Butler (1612-1680), the satirical poet best known for Hudibras. Soest’s Portrait of Samuel Butler, likely painted in the late 1650s or early 1660s, captures the writer's intellectual acuity and perhaps a hint of his sardonic wit. This portrait, like the Shakespeare one, contributed to Soest’s reputation for portraying men of letters.

Soest also painted members of the English aristocracy. His Portrait of Cecilius Calvert, 2nd Lord Baltimore (c. 1670) is a commanding image of the colonial proprietor of Maryland. The portrait conveys a sense of authority and gravitas, with Calvert depicted in rich attire, holding a map, symbolizing his role in the New World. The meticulous rendering of the lace collar and cuffs showcases Soest’s skill in depicting fine textiles.

The Portrait of Edward Herbert, 3rd Baron Herbert of Chirbury (1675-1678), now housed in Powis Castle, is another example of his work for the nobility. It displays Soest's mature style, with a confident handling of form and a sensitive portrayal of the sitter's character. The rich, dark tones and the focus on the sitter's face are typical of his approach.

His group portrait, William Fairfax and his wife Elizabeth (née Smith), though the exact date is unknown, demonstrates his ability to handle more complex compositions. The interaction, or lack thereof, between figures in such portraits often subtly conveyed contemporary marital ideals or social standing. Soest’s attention to the details of their attire and the domestic setting provides valuable insight into the material culture of the period.

A work titled Portrait of a Lady Seated at a Table with a Jewel Casket further exemplifies his skill. Such portraits often served not only to capture a likeness but also to display the sitter's wealth and status, with the jewel casket acting as a clear symbol of prosperity. The rendering of the lady's attire, the reflective surfaces, and the delicate handling of her features would have appealed to patrons seeking a dignified and realistic representation.

The Portrait of Michael Boyle, Archbishop of Armagh and Lord Chancellor of Ireland, is another testament to Soest's reach among influential figures of his time. Such ecclesiastical portraits required a blend of authority and piety, which Soest was capable of conveying through pose, expression, and the symbolic attributes of office.

The Artistic Milieu of Restoration England

To fully appreciate Gerard Soest's contribution, it's essential to understand the artistic environment in which he worked. The death of Van Dyck in 1641 had left a vacuum. During the Interregnum (1649-1660), portraiture continued, with artists like Robert Walker painting Oliver Cromwell and other Parliamentarian figures. However, the Restoration of Charles II in 1660 ushered in a new era of courtly patronage and a renewed demand for art that reflected the monarchy's splendor.

Sir Peter Lely quickly became the dominant force, his studio producing a vast number of portraits of courtiers, beauties (the "Windsor Beauties" series being a prime example), and naval heroes (the "Flagmen of Lowestoft"). Lely’s success was immense, and his style set the tone for much of English portraiture for two decades.

However, Lely was not the only significant painter. John Michael Wright (1617-1694), a Scottish Catholic painter, offered a distinct alternative to Lely, often with a greater degree of realism and psychological insight, particularly in his portraits of sitters in unique or ceremonial attire. Wright, like Soest, appealed to a clientele that perhaps sought something different from Lely's often formulaic elegance.

Other painters active during Soest's time in England included Cornelius Johnson (Jonson van Ceulen), another Dutch émigré who had been active since the reign of James I but left England during the Civil War, and later, the rising star Sir Godfrey Kneller (1646-1723). Kneller, of German origin, would eventually succeed Lely as the leading court painter and dominate English portraiture into the early 18th century. Soest’s career overlapped with the early part of Kneller's ascent.

Female artists were also beginning to make their mark, most notably Mary Beale (1633-1699), who ran a professional studio and was a contemporary of Soest. Her work, often characterized by a softer touch and warm palette, provides another point of comparison in the diverse London art scene. John Riley (1646-1691), an English-born painter, also rose to prominence towards the end of Soest's life, eventually becoming Principal Painter to William III and Mary II alongside Kneller.

Within this competitive environment, Soest maintained a steady practice. His Dutch training provided him with a solid technical foundation, and his style, while perhaps not as fashionable as Lely's at court, appealed to those who valued a more straightforward and less ostentatious form of representation. His portraits often possess a quiet dignity and an unembellished truthfulness.

Themes and Iconography

The primary theme in Soest's work, as with most portraitists of his era, was the representation of individual identity and status. Clothing, pose, and accompanying objects (books for scholars, maps for administrators, jewels for the wealthy) all played a role in constructing the sitter's public persona. Soest was adept at rendering these details, which were crucial for conveying the sitter's place in society.

His portraits of men often emphasize their public roles or intellectual pursuits. The depiction of Samuel Butler, for instance, focuses on his scholarly demeanor. In contrast, portraits of women, like the Lady Seated at a Table with a Jewel Casket, often highlighted domestic virtues, beauty, or wealth, reflecting the societal expectations of the time.

The user's provided information mentions a reference to Ceres, the Roman goddess of agriculture, in relation to Soest's work. If Soest incorporated such mythological allusions, it would align with a broader Baroque tradition of using classical symbolism to elevate or add layers of meaning to portraits, perhaps suggesting fertility, abundance, or a connection to the land for aristocratic sitters. However, without specific examples of such works being widely known, this remains a more general observation about potential thematic content in the era.

Later Career, Death, and Legacy

Gerard Soest continued to paint throughout the 1660s and 1670s. Despite his relative success and consistent output, he seems to have remained somewhat outside the main currents of courtly patronage. This might have been due to his less flamboyant style, or perhaps a personal disinclination towards the intrigues of the court. Some anecdotal accounts suggest he could be somewhat brusque or difficult with sitters, particularly women, if he felt they were overly concerned with vanity. If true, this temperament might have limited his appeal in circles where flattery was often expected.

He died in London in February 1681 and was buried at St. Martin-in-the-Fields. His will mentions a son, also named Gerard.

Gerard Soest’s legacy lies in his contribution to the rich tapestry of 17th-century English portraiture. He represents a strand of Dutch-influenced realism that provided an alternative to the more dominant Van Dyckian and Lelyesque modes. His portraits are valuable historical documents, offering insights into the appearance and character of a range of individuals from Stuart England.

His posthumous portrait of Shakespeare, in particular, has ensured his name remains known beyond specialist art historical circles. The desire for authentic images of great figures like Shakespeare meant that portraits, even those created long after the subject's death, played a crucial role in shaping public perception.

While perhaps overshadowed by figures like Lely or Kneller in terms of fame and influence on subsequent generations, Soest's work is appreciated today for its honesty, technical skill, and the quiet intensity of his characterizations. His paintings can be found in numerous public collections, including the National Portrait Gallery in London, and in various private and stately home collections, testament to his enduring, if understated, significance in the history of British art. He was a skilled practitioner who brought a distinct Netherlandish sensibility to the English art scene, enriching it with his particular vision of portraiture.