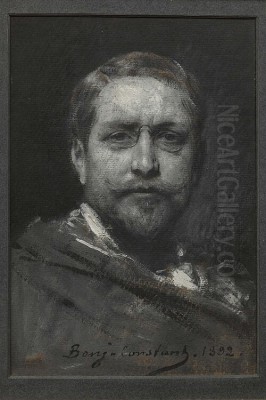

Jean-Joseph Benjamin-Constant (born June 10, 1845, Paris – died May 26, 1902, Paris) stands as a significant figure in late 19th-century French art. A highly skilled painter and etcher, he achieved considerable fame during his lifetime, celebrated primarily for his dramatic Orientalist scenes and his commanding portraits of the European and American elite. Operating within the established academic tradition, Constant navigated the vibrant Parisian art world, leaving behind a legacy of visually rich and technically accomplished works that captured the imagination of his contemporaries.

Early Life and Academic Foundations

Born Jean-Joseph Constant in Paris, he later adopted the hyphenated "Benjamin-Constant" to distinguish himself, perhaps partly from the earlier writer and politician Henri-Benjamin Constant de Rebecque, though they were unrelated. His artistic inclinations emerged early. Following foundational studies at the École des Beaux-Arts in Toulouse, where the legacy of artists like Jean-Auguste-Dominique Ingres was strong, Constant moved back to Paris to further his training at the prestigious École des Beaux-Arts.

In Paris, he entered the studio of Alexandre Cabanel, one of the most influential academic painters of the Second Empire and Third Republic. Cabanel, known for works like The Birth of Venus, was a master of smooth finish, elegant composition, and historical or mythological subjects. Under Cabanel's tutelage, Constant honed his draughtsmanship and compositional skills, absorbing the tenets of the academic style that emphasized historical accuracy (or perceived accuracy), careful modelling of form, and a high degree of finish. His early Salon debut came in 1869 with Hamlet et le Roi (Hamlet and the King), now housed in the Musée d'Orsay, demonstrating his ambition to tackle literary and historical themes from the outset.

The Allure of the Orient

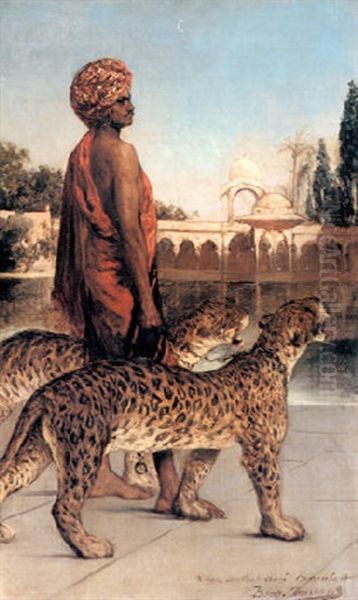

A pivotal moment in Benjamin-Constant's career was his journey to Spain and Morocco in 1871-1872. This trip, undertaken partly via an official diplomatic mission, exposed him to the intense light, vibrant colours, distinct cultures, and architectural splendours of North Africa. Like many European artists before him, most notably the Romantic giant Eugène Delacroix whom Constant admired, he was captivated by the perceived exoticism and drama of the region. Delacroix's own Moroccan sketchbooks and paintings from the 1830s had already established a powerful precedent for French Orientalist art.

Constant returned to Paris armed with sketches, experiences, and a newfound thematic focus that would dominate his work for the next decade or so. His Orientalist paintings are characterized by their rich colour palettes, dramatic lighting, often large scale, and subjects drawn from Moroccan history, courtly life, and imagined scenes of harem interiors or public spaces. He sought to convey the intensity and sensuality he associated with the 'Orient,' a term used broadly and often stereotypically by Europeans at the time to encompass North Africa and the Middle East.

His Salon submissions during the 1870s cemented his reputation as a leading Orientalist painter. Works like Prisonniers marocains (Moroccan Prisoners, 1875, Musée d'Orsay) depicted the harsh realities or perceived barbarity of the region, while others like Femmes de Riff (Maroc) (Riffian Women (Morocco)) focused on the portrayal of local people. Le Soir sur les Terrasses (Maroc) (Evening on the Terraces (Morocco), 1879) offered a more atmospheric and languid view of daily life, showcasing his skill in rendering fabrics and the effects of twilight.

Perhaps his most ambitious Orientalist work was L'Entrée de Méhémet II à Constantinople, le 29 mai 1453 (The Entry of Mehmet II into Constantinople, 29 May 1453), exhibited at the Salon of 1876. This enormous canvas, now in the Musée des Augustins, Toulouse, depicted the Ottoman conquest with dramatic flair, focusing on the triumphant sultan amidst the spoils of war and the vanquished. The painting was a sensation, earning Constant a first-class medal and solidifying his fame. It exemplified the historical grandiosity and sometimes violent undertones present in much Orientalist art of the period.

Constant's approach differed from some of his contemporaries. While sharing a meticulous attention to detail in rendering costumes and settings, akin to the highly polished works of Jean-Léon Gérôme, Constant often employed a looser brushwork and a more overtly dramatic, almost theatrical, sense of composition, perhaps reflecting the enduring influence of Delacroix. His work can also be compared to other French Orientalists like Eugène Fromentin or Gustave Guillaumet, who also travelled extensively in North Africa, though each developed their own distinct style and focus. The tragic early death of the gifted young Orientalist painter Henri Regnault in the Franco-Prussian war (1871) may have also created a space in the Parisian art scene that Constant helped to fill.

Master Portraitist of the Belle Époque

By the 1880s, while still occasionally revisiting Orientalist themes, Benjamin-Constant increasingly turned his attention to portraiture. This shift coincided with a growing demand for portraits among the burgeoning wealthy classes of Europe and America during the Belle Époque. Constant quickly established himself as one of the most sought-after portrait painters of his generation, particularly favoured by British aristocracy and wealthy Americans.

His portrait style was typically grand and imposing, designed to convey the status, wealth, and character of his sitters. He employed rich colours, paid close attention to the luxurious textures of clothing and interiors, and often used dramatic lighting to enhance the presence of the figure. His technical facility, honed through his academic training and Orientalist work, allowed him to capture likenesses effectively while imbuing his portraits with a sense of dignity and importance.

Among his notable sitters were prominent figures from royalty, politics, and society. He painted a posthumous portrait of Queen Victoria for the Hôtel de Ville in Paris, and later painted Queen Alexandra of the United Kingdom (1901). His portrait of Pope Leo XIII (1901) was also a significant commission. He captured the likenesses of influential figures like the Marquis of Dufferin and Ava (Viceroy of India), the prominent journalist Henri Blowitz (1902), and members of powerful families like the Vanderbilts. His success in London was particularly notable, making him a rival to other fashionable portraitists of the day.

His style can be compared to that of his French contemporaries like Léon Bonnat, another student of Cabanel who became a celebrated portraitist known for his sober realism, or Carolus-Duran, known for his more flamboyant, painterly approach and as the teacher of John Singer Sargent. Indeed, Constant's work often invites comparison with Sargent, the American expatriate painter whose dazzling brushwork and psychological insight set a high bar for society portraiture. While Constant's portraits might sometimes lack the sheer virtuosity or penetrating depth of Sargent's best work, they possess a solid, confident presence and a mastery of academic technique that appealed greatly to his clientele.

Monumental Decorations and Public Art

Beyond easel painting, Benjamin-Constant was also a prolific creator of large-scale decorative murals for public buildings, a significant aspect of artistic production during the French Third Republic. The regime actively commissioned art to adorn new or refurbished civic structures, aiming to promote republican values, celebrate French culture, and provide work for artists trained in the academic tradition. Constant secured several prestigious commissions.

He contributed significantly to the decorations of the rebuilt Hôtel de Ville (City Hall) in Paris, painting allegorical figures and scenes in the Salons. One of his most famous mural projects was for the Sorbonne, the heart of the University of Paris. He decorated the Salle des Autorités and contributed to the Grand Amphithéâtre, creating vast allegorical compositions celebrating learning and the arts. These works, designed to be integrated with the architecture, showcased his ability to handle complex, multi-figure compositions on a monumental scale.

He also painted ceiling decorations for the Opéra-Comique theatre in Paris, depicting themes related to music and performance, completed around 1898-1899. Further afield, he executed murals for the Capitole, the city hall of Toulouse, the city where he had received his early training. These large-scale works, often allegorical and historical in nature, required careful planning and execution, demonstrating his versatility and his standing within the official art establishment. His style in these murals remained broadly academic, characterized by clear compositions, idealized figures, and a rich, often symbolic use of colour, fitting the didactic and celebratory purpose of such public art. His contributions place him alongside other major muralists of the era, such as Pierre Puvis de Chavannes, though Constant's style was generally more robust and less ethereal than that of Puvis.

Style, Technique, and Recognition

Benjamin-Constant's art is fundamentally rooted in the French academic tradition learned under Cabanel. This provided him with a strong foundation in drawing, anatomy, and composition. However, his work was infused with elements drawn from Romanticism, particularly the influence of Delacroix, evident in his love of dramatic subjects, rich colour, and dynamic arrangements. His Orientalist paintings, especially, showcase his skill as a colourist, using juxtapositions of warm and cool tones, deep shadows, and brilliant highlights to create powerful effects.

He possessed considerable technical skill in rendering different textures – the gleam of silk, the richness of velvet, the coolness of marble, the warmth of flesh. This facility served him well in both his exotic Orientalist scenes and his formal portraits. While adept at creating a sense of realism, his work often prioritized dramatic effect and idealized representation over strict naturalism. He was less concerned with capturing fleeting moments of light and atmosphere in the manner of his Impressionist contemporaries like Claude Monet or Edgar Degas, whose revolutionary approach to painting represented a fundamental challenge to the academic establishment Constant belonged to. He also practiced etching, producing prints often related to his painted subjects.

Throughout his career, Benjamin-Constant enjoyed significant official recognition and commercial success. He was a regular and prominent exhibitor at the Paris Salon, the main venue for artists seeking public acclaim and patronage. He received numerous awards, including medals in 1875 (Second Class), 1876 (First Class for The Entry of Mehmet II), and was progressively honoured by the French state through the Legion of Honour, being made a Chevalier in 1878, an Officer in 1884, and finally a Commander in 1900.

His success extended to teaching. He taught at the Académie Julian, a private art school in Paris that attracted students from around the world, including many Americans. His influence was further solidified by his election to the prestigious Institut de France (Académie des Beaux-Arts) in 1893, taking the seat left vacant by the death of his former master, Alexandre Cabanel. This marked his ascent to the highest echelons of the French art world, joining the ranks of other highly successful academic painters like William-Adolphe Bouguereau and Ernest Meissonier. He was, by the end of his life, a respected and decorated pillar of the artistic establishment.

Legacy and Conclusion

Jean-Joseph Benjamin-Constant died in Paris in 1902 at the height of his fame. He left behind a substantial body of work encompassing historical scenes, exotic Orientalist fantasies, grand society portraits, and monumental public murals. He successfully navigated the demands of the official Salon system and the tastes of wealthy international patrons, achieving a level of success envied by many artists of his time.

For much of the 20th century, like many academic artists of his generation, Benjamin-Constant's reputation suffered a decline as modernist aesthetics came to dominate art history narratives. His work was often dismissed as overly theatrical, conservative, or merely illustrative. However, in recent decades, there has been a renewed scholarly and public interest in 19th-century academic art, including Orientalism and society portraiture.

Today, Benjamin-Constant is recognized as a highly skilled painter who excelled in multiple genres. His Orientalist works are studied for their artistic qualities as well as for what they reveal about 19th-century European perceptions of other cultures. His portraits stand as important documents of the Belle Époque elite, captured with technical assurance and a keen sense of presence. His murals remain significant examples of the large-scale public art projects of the French Third Republic. While perhaps not an innovator on the scale of the Impressionists or Post-Impressionists, Jean-Joseph Benjamin-Constant was a consummate professional, a master technician, and a major figure in the complex and vibrant art world of late 19th-century France, whose works continue to engage viewers with their colour, drama, and skill. His contemporaries included not only his teacher Cabanel and influence Delacroix, but also fellow Orientalists like Gérôme, Fromentin, Guillaumet, and Regnault, portraitists like Bonnat, Carolus-Duran, Sargent, and James Tissot, and academic giants like Bouguereau, Meissonier, and the muralist Puvis de Chavannes, situating him firmly within the artistic landscape of his era.