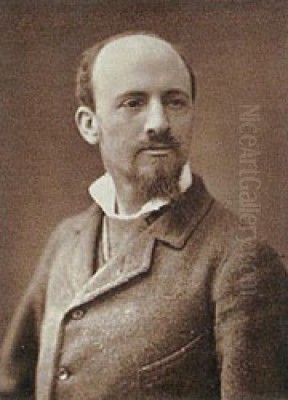

Gustave Jean Jacquet stands as a significant figure in the landscape of 19th-century French art. Born in Paris on May 25, 1846, he dedicated his life to capturing beauty and elegance, primarily through his celebrated portraits and genre scenes. Operating within the dominant Academic tradition of his time, Jacquet carved a distinct niche for himself, becoming renowned for his technical skill, vibrant palette, and charming depictions of historical and contemporary femininity. His life and work offer a fascinating window into the artistic tastes and cultural milieu of Paris during the latter half of the 19th century.

Early Life and Academic Foundations

Paris, the undisputed center of the Western art world in the 19th century, was the lifelong home of Gustave Jacquet. He entered the prestigious École des Beaux-Arts, the cornerstone of official art education in France. Crucially, he became a pupil of William-Adolphe Bouguereau, one of the most successful and influential Academic painters of the era. Bouguereau's studio was a highly sought-after training ground, known for instilling rigorous draftsmanship, a smooth, highly finished technique (known as léché), and a focus on idealized subject matter, often drawn from mythology or allegory, alongside polished portraiture.

The influence of Bouguereau is certainly discernible in Jacquet's early work. The emphasis on precise drawing, graceful composition, and a certain idealized beauty reflects the standards upheld by his master and the Academy. However, Jacquet quickly began to assert his own artistic personality, moving away from the mythological or overtly allegorical themes often favored by Bouguereau, and focusing more intently on historical genre scenes and intimate portraits of women, imbued with a distinct charm and vitality.

Salon Debut and Rising Recognition

The Paris Salon, the official annual or biennial art exhibition sponsored by the French state, was the primary venue for artists to gain recognition, attract patrons, and establish their careers. A successful debut at the Salon could launch an artist's trajectory. Jacquet made his first appearance at the Salon in 1865, exhibiting works such as La Modestie (Modesty) and La Tristesse (Sadness). These early submissions already hinted at his predilection for depicting feminine grace and emotion.

Shortly thereafter, his painting La Rêverie (The Daydream), exhibited at the Salon, garnered significant positive attention from critics. This success marked his formal arrival on the Parisian art scene. It demonstrated his technical proficiency, learned under Bouguereau, but also showcased his developing individual style – a focus on capturing a mood, often contemplative or subtly playful, within a beautifully rendered figure. This early acclaim set the stage for a long and successful career, characterized by regular participation in the Salons.

Another notable early work was L'appel aux Armes (Call to Arms) shown in 1867, followed by Sortie d'armée (Army Leaving) in 1868, indicating an early exploration of historical military themes, often featuring meticulously rendered period costumes, a subject that would become a hallmark of his genre work, though often on a more intimate scale. These works displayed his skill in handling more complex compositions and historical detail.

Artistic Style: Elegance, Detail, and Vibrancy

Gustave Jacquet's mature style is characterized by several key elements. He possessed an extraordinary talent for rendering textures, particularly the luxurious fabrics favored in the historical costumes he often depicted. Silk, satin, velvet, and lace seem almost tangible under his brush, catching the light with convincing realism. This meticulous attention to detail extended to jewelry, accessories, and the settings of his paintings, creating a world of refined elegance.

His palette was typically rich and vibrant. He employed strong, clear colors, often juxtaposing them to create lively and visually appealing compositions. While adhering to the principles of Academic realism in terms of form and finish, his use of color often lent his works a decorative quality that appealed greatly to the tastes of the time. His brushwork, especially in his oil paintings, was generally smooth and highly finished, leaving little trace of the artist's hand, a characteristic valued within the Academic tradition championed by figures like Bouguereau and Jean-Léon Gérôme.

Jacquet excelled in capturing the human figure, particularly women. His subjects often possess a sense of vitality and personality, whether depicted in quiet contemplation, engaging in leisurely pursuits, or displaying a hint of coquettish charm. While idealized according to the conventions of the era, his figures rarely feel stiff or lifeless; instead, they project a sense of presence and individuality. This ability to combine technical polish with psychological nuance was central to his appeal.

Genre Scenes: Echoes of History

A significant portion of Jacquet's oeuvre consists of genre paintings, often relatively small in scale, depicting scenes inspired by the 16th, 17th, and 18th centuries. These works frequently feature solitary female figures or small groups in elaborate historical costumes, engaged in activities like reading, playing music, or simply posing elegantly within richly decorated interiors or idealized landscapes. Works like La Bienvenue (The Welcome) or The Musician exemplify this aspect of his production.

These historical evocations tapped into a popular taste for nostalgia and romanticized visions of the past, a trend also visible in the work of contemporaries like Ernest Meissonier, known for his incredibly detailed historical military scenes, albeit often with a more masculine focus. Jacquet's contribution was to infuse these historical settings with feminine grace and charm. His paintings offered viewers an escape into a world perceived as more elegant and picturesque than the rapidly industrializing present. The meticulous rendering of historical attire also showcased his considerable skill and research.

His famous Jeune fille tenant une épée (Young Girl Holding a Sword) from 1876 combines his interest in historical costume (evoking perhaps the era of the Three Musketeers) with a striking female figure, demonstrating his ability to blend historical genre with portrait-like intensity. These works were highly sought after by collectors who appreciated their decorative qualities and technical finesse.

Master Portraitist

Alongside his genre scenes, Jacquet was a highly accomplished portrait painter. He captured the likenesses of numerous society figures, particularly women, often portraying them with the same elegance and attention to detail found in his historical works. His portraits, while fulfilling the primary function of recording a sitter's appearance, also function as sophisticated works of art in their own right. He skillfully balanced likeness with idealization, presenting his subjects in a flattering yet recognizable manner.

His approach to portraiture can be situated within the broader context of late 19th-century society portraiture. While perhaps not possessing the flamboyant brushwork of a Giovanni Boldini or the penetrating psychological depth sometimes found in the work of John Singer Sargent (both younger contemporaries), Jacquet offered a refined, polished, and undeniably beautiful vision of his sitters. His style shares affinities with other successful French portraitists of the era like Léon Bonnat or Carolus-Duran (Sargent's own teacher), who also combined technical mastery with social elegance.

Representative examples like Portrait of a Woman (numerous exist, often identified by the sitter if known, or simply by description like Girl in Green Dress or Girl in Riding Habit) showcase his ability to capture not just physical features but also the textures of clothing and the subtle nuances of expression. These portraits cemented his reputation among the affluent clientele of Paris and beyond.

Recognition and Official Acclaim

Jacquet's consistent quality and popular appeal earned him significant recognition within the official art establishment. He received medals at the Salons, including a third-class medal as early as 1868, and a medal of excellence in 1875. The culmination of this official recognition came in 1879 when he was made a Chevalier (Knight) of the Légion d'honneur (Legion of Honour), one of France's highest civilian decorations. This award signified his status as a respected and successful artist within the Academic system.

Receiving the Legion of Honour was a major milestone for any artist of the period. It confirmed his standing alongside other decorated pillars of the art establishment, such as his former master Bouguereau, and other luminaries like Alexandre Cabanel and Jean-Léon Gérôme. This official sanction further boosted his reputation and desirability among patrons. His works were acquired by the French state for regional museums and eagerly sought by private collectors in France, Britain, and America.

His success occurred during a period of intense artistic ferment in Paris. While Jacquet thrived within the established Salon system, this was also the era of the Impressionist revolution. Artists like Claude Monet, Pierre-Auguste Renoir, Edgar Degas, Camille Pissarro, and Alfred Sisley were challenging the very foundations of Academic art with their focus on capturing fleeting moments, the effects of light, and scenes of modern life, often using looser brushwork and brighter palettes. Jacquet, however, remained steadfastly committed to the Academic ideals of finish, detail, and traditional subject matter, catering to a different, though substantial, segment of the art market.

The Parisian Art World Context

To fully appreciate Jacquet's position, it's essential to view him within the vibrant and competitive art world of late 19th-century Paris. The Academy and the Salon system, though increasingly challenged, still held considerable sway. Jacquet navigated this system successfully, aligning himself with its aesthetic values. His work found favor alongside that of other popular Academic and juste milieu painters who blended academic technique with appealing subject matter.

His focus on elegant women in contemporary or historical settings resonates with the work of artists like the Belgian Alfred Stevens, who specialized in depicting fashionable Parisian women in luxurious interiors, or James Tissot, whose detailed paintings chronicled the social life of the upper classes in Paris and London. While Jacquet often leaned more towards historical costume, the underlying appeal of elegance and refined femininity was a shared characteristic. He can also be seen in dialogue with Jean Béraud, who captured the bustling social life of Parisian boulevards and salons, though Béraud's style was often sketchier and more focused on contemporary narrative.

Even the Realist movement, spearheaded earlier by Gustave Courbet and Jean-François Millet, provides a contrasting backdrop. While Jacquet employed realistic techniques, his subject matter was far removed from the depictions of rural labor or unvarnished social commentary favored by the Realists. Jacquet's realism was polished, idealized, and aimed at charm and beauty rather than gritty truth.

Later Career and Enduring Themes

Jacquet continued to paint prolifically throughout his later career, largely maintaining the style and themes that had brought him success. He remained a regular exhibitor at the Salon and other venues. His technical skill did not diminish, and he continued to produce exquisite portraits and charming historical genre scenes until his death. He also worked in watercolor, bringing a similar delicacy and precision to that medium.

His dedication to his specific niche – the elegant female figure, often in historical dress, rendered with meticulous detail and vibrant color – meant that his style did not undergo radical transformations in the manner of artists exploring Impressionism or Post-Impressionism. He found a successful formula early on and refined it throughout his life, satisfying a consistent demand from patrons who admired his particular brand of beauty and craftsmanship.

His studio, located in Paris, was undoubtedly a place of diligent work, producing the highly finished canvases that collectors expected. The consistency of his output speaks to a disciplined work ethic and a clear artistic vision, albeit one firmly rooted in the traditions he had mastered.

Legacy and Reappraisal

Gustave Jean Jacquet passed away in Paris on July 12, 1909, at the age of 63. Following his death, the contents of his studio were auctioned, a common practice at the time. For much of the 20th century, as Modernism came to dominate art historical narratives, Jacquet and many of his Academic contemporaries fell somewhat out of favor. Their emphasis on technical finish and traditional subject matter was often dismissed as conservative or merely decorative compared to the innovations of the avant-garde movements.

However, the late 20th and early 21st centuries have witnessed a significant reappraisal of 19th-century Academic art. Art historians and collectors have begun to appreciate anew the extraordinary technical skill, aesthetic appeal, and cultural significance of artists like Jacquet. His works are now recognized for their intrinsic quality and as important documents of the tastes and aspirations of their time.

Today, Jacquet's paintings can be found in numerous museum collections, including the Musée d'Orsay in Paris, various regional French museums, and institutions internationally, such as the Chi Mei Museum in Taiwan, which holds a notable example. His works also command strong prices at auction, indicating a renewed appreciation among private collectors. Furthermore, his detailed and accurate rendering of historical costume has been noted for its influence, providing inspiration for fashion and costume designers seeking to evoke past eras.

Conclusion

Gustave Jean Jacquet was a quintessential painter of elegance and charm in late 19th-century France. Trained by the great William-Adolphe Bouguereau, he mastered the techniques of the Academic tradition but applied them with his own distinct sensibility, focusing on captivating depictions of women, both in contemporary portraits and romanticized historical genre scenes. His work is characterized by meticulous detail, particularly in the rendering of luxurious fabrics, a vibrant color palette, and a refined, polished finish.

While working during the tumultuous rise of Impressionism, Jacquet remained committed to Academic ideals, achieving significant success and official recognition, including the prestigious Legion of Honour. Though his reputation waned during the dominance of Modernism, recent decades have seen a renewed appreciation for his technical brilliance and the undeniable appeal of his art. As a master of depicting historical elegance and feminine grace, Gustave Jean Jacquet holds a secure and respected place in the rich tapestry of 19th-century French painting. His art continues to delight viewers with its beauty, craftsmanship, and evocative charm.