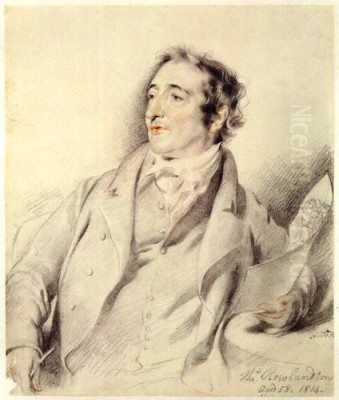

Thomas Rowlandson stands as one of the most significant and prolific figures in British art during the late Georgian period. Born in London in 1756 and living until 1827, his career spanned a transformative era in British society, politics, and culture. Primarily celebrated as a caricaturist and printmaker, Rowlandson was also a highly skilled watercolourist and draughtsman. His vast body of work provides an unparalleled visual commentary on the manners, morals, fashions, and follies of his time, capturing the vibrant, often chaotic, energy of life from the highest echelons of society to the bustling streets and taverns frequented by ordinary Londoners. His keen eye for detail, combined with a robust sense of humour and a fluid, expressive line, made him a master of social observation and satire.

Early Life and Artistic Formation

Thomas Rowlandson was born in July 1756 in the City of London's Old Jewry district. His father was involved in trade, sometimes described as a textile merchant or weaver, but faced financial difficulties, eventually leading to bankruptcy around 1759. This downturn in family fortunes meant young Thomas was largely supported and raised by a relative, often identified as a wealthy aunt or uncle, possibly a Madame Chatelier. This support allowed him access to a good education, initially at Dr. Barvis's academy in Soho Square, an institution known for nurturing artistic talent.

His artistic promise was evident early on, leading him to enroll at the Royal Academy Schools perhaps as young as 16. The Royal Academy, founded under the patronage of King George III and led by Sir Joshua Reynolds, was the premier institution for artistic training in Britain. Here, Rowlandson honed his skills in drawing and composition. Crucially, his education was broadened by travels to Paris, possibly funded by his aunt. He is said to have studied there, perhaps intermittently, potentially even under the sculptor Jean-Baptiste Pigalle, although details remain somewhat unclear. These trips exposed him to contemporary French art, particularly the lingering elegance and fluidity of the Rococo style, associated with artists like Jean-Antoine Watteau and François Boucher, which would subtly inform his own developing aesthetic.

The Shift to Satire and Caricature

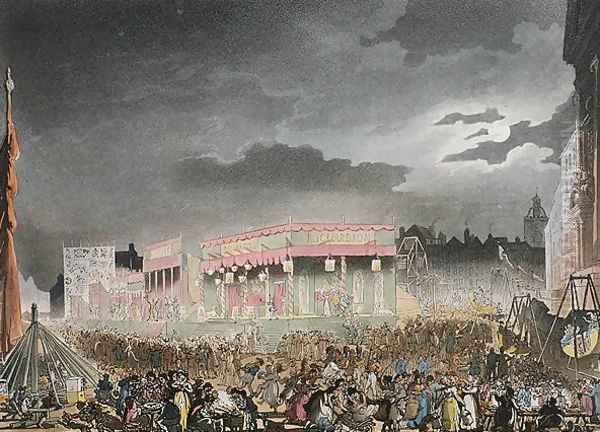

Rowlandson initially pursued a career path more typical for an academically trained artist, focusing on portraiture and historical or mythological subjects. He exhibited works at the Royal Academy exhibitions, including figure compositions and portraits. Some early works, like his ambitious drawing Vauxhall Gardens (1784), showcased his ability to handle complex multi-figure scenes with elegance and observational skill, hinting at his future direction but still operating within a more conventional artistic framework.

However, the burgeoning market for satirical prints and caricatures in Georgian London offered a more lucrative and perhaps more temperamentally suited avenue. The late 18th century was a golden age for British graphic satire, with artists like William Hogarth having paved the way decades earlier. Rowlandson found his true calling in observing and humorously exaggerating the life around him. While he continued to produce watercolours and drawings appreciated for their artistic merit, his fame and income increasingly derived from designs for etchings, often hand-coloured, that lampooned social types, political events, and human weaknesses. This shift allowed him to combine his considerable artistic skill with a sharp wit and an unblinking eye for the absurdities of contemporary life.

Artistic Style and Techniques

Rowlandson developed a distinctive and highly recognizable style characterized by its energy, fluidity, and calligraphic line. He typically worked with pen and ink, often over a light pencil sketch, applying watercolour washes with remarkable dexterity and transparency. His line is dynamic and expressive, capable of capturing movement and character with seemingly effortless grace. While influenced by the elegance of the French Rococo, particularly in his compositional arrangements and sometimes delicate colour palettes, Rowlandson's work possesses a fundamentally English robustness and earthiness.

His figures are often rounded and fleshy, rendered with a certain gusto that can range from gentle humour to outright bawdiness. Unlike the biting, often savage political invective of his great contemporary, James Gillray, Rowlandson's satire tended to be more generalized, focusing on social types and universal human failings like gluttony, lechery, vanity, and pomposity. His approach was often more observational and amused than overtly condemnatory.

He was a master of etching, translating his lively drawings into prints that could be widely disseminated. Working frequently with the publisher Rudolph Ackermann, Rowlandson's designs were etched onto copper plates, printed, and then often hand-coloured by teams of colourists, making the final prints vibrant and appealing. This combination of skilled draughtsmanship, watercolour technique, and printmaking expertise allowed him to be incredibly prolific, producing thousands of images throughout his career.

Chronicling London Life: High and Low

London, in all its teeming diversity, was one of Rowlandson's greatest subjects. He captured the fashionable world of the West End, depicting elegant gatherings, assemblies, and promenades in places like Hyde Park or the aforementioned Vauxhall Gardens. These scenes often gently satirize the pretensions and interactions of the beau monde, showcasing the latest fashions and social rituals. His famous depiction of Vauxhall Gardens is a masterpiece of social panorama, filled with recognizable figures and capturing the unique atmosphere of this popular pleasure garden.

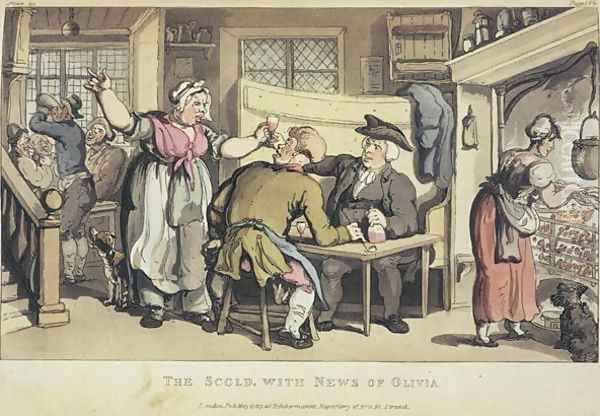

Simultaneously, Rowlandson turned his gaze to the less glamorous aspects of city life. He depicted bustling street scenes, crowded markets, rowdy taverns, coaching inns, and even the grim realities of prisons and hospitals. His work provides invaluable visual documentation of the everyday life of ordinary Londoners – shopkeepers, artisans, soldiers, sailors, street vendors, beggars, and prostitutes. These scenes are rendered with the same energy and attention to detail as his depictions of high society, often highlighting the humour and resilience found in less privileged circumstances, though sometimes employing stereotypes common to the era. Series like London Street Life exemplify this aspect of his work.

Social Satire: Types and Follies

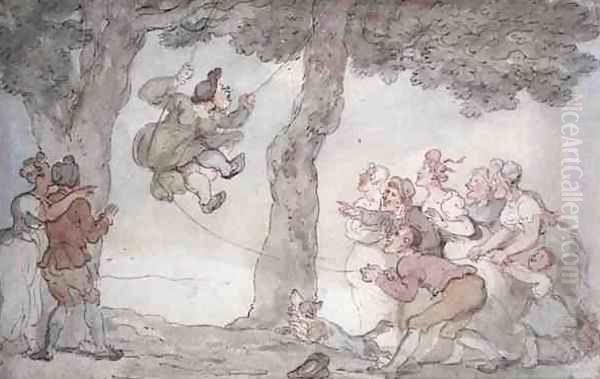

Rowlandson excelled at creating memorable social types, often exaggerated for comic effect. His prints frequently targeted the professions: pompous doctors with dubious remedies (as seen in works sometimes titled The Swing or featuring characters like Doctor Botherum), grasping lawyers entangled in arcane procedures, and worldly clergymen more interested in earthly pleasures than spiritual matters. Antiquarians obsessed with trivial artifacts, ageing dandies desperately clinging to youth, corpulent aldermen indulging in feasts, and naive country folk bewildered by the city were all recurring figures in his satirical repertoire.

He also humorously depicted common human experiences and failings – the discomforts of travel, the perils of gambling (a subject Rowlandson knew firsthand), the awkwardness of courtship, the chaos of domestic life, and the effects of excessive drinking. While often critical, his satire usually contains an element of affectionate amusement, suggesting a certain tolerance for human imperfection. He observed the social comedy around him and invited his audience to share in the laughter, rather than delivering harsh moral judgments in the vein of Hogarth. Works like Money Lenders capture the predatory nature of certain financial dealings with characteristic wit.

Political Commentary

While James Gillray is generally considered the foremost political caricaturist of the era, Rowlandson also produced a significant number of prints commenting on political events and figures. His political satire, however, tended to be less specific and less venomous than Gillray's. He addressed major events like the Napoleonic Wars, often depicting the hardships faced by soldiers or satirizing figures like Napoleon Bonaparte himself, sometimes in allegorical prints like the suggested Puss in Boots reference.

He also touched upon domestic politics, including elections, parliamentary debates, and the actions of prominent politicians. However, his interest often seemed to lie more in the general human comedy surrounding political life – the pomposity of officials, the chaos of crowds, the absurdity of certain situations – rather than detailed partisan attacks. His collaboration with Ackermann on The Microcosm of London included views of significant political and civic institutions, though the primary focus there was topographical and descriptive, albeit enlivened by Rowlandson's figures.

The Picturesque and Landscape

Beyond the confines of London and social satire, Rowlandson possessed a genuine talent for landscape and the picturesque. He undertook numerous sketching tours throughout Britain, visiting regions like Devon, Cornwall, Wales, and the Lake District, as well as travelling on the Continent to France, Flanders, Holland, and Germany. These journeys resulted in a large number of watercolours and drawings depicting scenic views, rural life, coastal scenes, and the incidents of travel.

Works like Valley of Stones, Lynton, Devon or The arrival of the coach at Bodmin, Cornwall showcase his ability to capture the atmosphere of a place with fluid lines and delicate washes. While often incorporating figures and narrative elements – coaches arriving, travellers resting, locals going about their business – these works demonstrate a sensitivity to natural beauty and architectural detail. His landscape style contrasts with the more formal topographical tradition represented by artists like Paul Sandby, offering a looser, more anecdotal approach. These picturesque views were popular and formed a significant part of his output, often sold as individual watercolours or used as designs for prints.

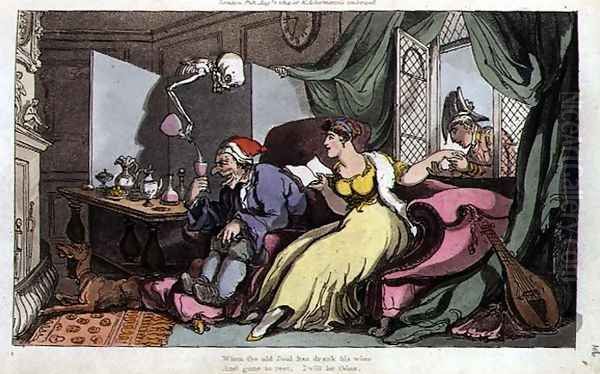

The Macabre and Mortality: The Dance of Death

A notable, darker strand in Rowlandson's work is his engagement with themes of mortality, most famously in the series The English Dance of Death (published 1815-16 with verses by William Combe). Reviving a medieval allegorical tradition, these prints depict Death, personified as a skeleton, intruding upon scenes from all walks of life, claiming victims regardless of age, rank, or wealth.

Rowlandson's treatment of the theme is characteristically robust and often darkly humorous. Death appears unexpectedly at feasts, balls, gambling dens, sickbeds, and battlefields. While the underlying message is serious – the universality and inevitability of death – the depictions are often energetic and even grotesque, blending the macabre with social satire. This series, along with related works, shows Rowlandson exploring the grimmer realities beneath the surface of Georgian society's pursuit of pleasure and status.

Major Works and Series

Rowlandson's fame rests significantly on several major series and publications, often produced in collaboration with writers and publishers.

The Three Tours of Doctor Syntax: Perhaps his most famous collaboration, this series featured the adventures of a pedantic and eccentric clergyman-schoolmaster, Doctor Syntax, as he travelled in search of the picturesque. The humorous verses were provided by William Combe, and Rowlandson's illustrations (published by Ackermann between 1812 and 1821) proved immensely popular. The character of Doctor Syntax became a household name, and the series perfectly blended Rowlandson's talent for landscape, social observation, and gentle character satire.

The Microcosm of London: Published by Ackermann (1808-1810), this ambitious project featured architectural renderings of London's famous buildings and landmarks by Augustus Charles Pugin, with Rowlandson adding the lively human figures that populated these scenes. This collaboration combined topographical accuracy with Rowlandson's characteristic animation, creating a vivid portrait of the city's public spaces and institutions.

The English Dance of Death: As mentioned earlier, this series (1815-16), again with Combe providing verses and Ackermann publishing, was a significant exploration of mortality through satirical vignettes.

Vauxhall Gardens (1784): Although an earlier, standalone work, this large and detailed drawing (later engraved) remains one of his most celebrated depictions of London social life, showcasing his skill in composition and observation before he fully dedicated himself to caricature.

Illustrations for Literary Works: Rowlandson provided illustrations for editions of classic novels by authors such as Tobias Smollett (Roderick Random, Peregrine Pickle), Oliver Goldsmith (The Vicar of Wakefield), and Laurence Sterne (A Sentimental Journey). He also illustrated humorous works and periodicals like The Poetical Magazine, where Doctor Syntax first appeared.

Rowlandson the Man: Personality and Lifestyle

Contemporary accounts and biographical anecdotes paint a picture of Rowlandson as a convivial, if somewhat improvident, character. He inherited a significant sum (£7,000) from his Parisian aunt but reportedly gambled it away quickly. His fondness for gambling, drinking, and lively company seems to have been well-known. He was a regular figure in London's taverns and gaming houses, experiences that undoubtedly fuelled his art.

Despite his sometimes dissolute lifestyle, he was capable of sustained hard work, producing an enormous volume of drawings and prints over his long career. He remained a lifelong bachelor but was known for his appreciation of female beauty, a frequent subject in his art, often depicted with a sensual frankness. He maintained friendships with fellow artists, notably the painter of rural scenes, George Morland, with whom he sometimes sketched and caroused. This blend of artistic dedication and personal indulgence seems characteristic of the man and is reflected in the energetic, sometimes Rabelaisian, quality of his work.

Contemporaries and Context: The Golden Age of Caricature

Rowlandson worked during what is often called the "Golden Age of English Caricature," roughly from the 1770s to the 1820s. He shared the stage with other notable talents:

James Gillray (1756-1815): Rowlandson's main rival, known for his fierce, complex, and often savage political satires. While Rowlandson's focus was broader and often gentler, Gillray excelled at biting political commentary.

William Hogarth (1697-1764): Though preceding Rowlandson, Hogarth's "modern moral subjects" and pioneering use of narrative prints laid the groundwork for the entire school of English satire.

Isaac Cruikshank (1764-1811) and his son George Cruikshank (1792-1878): Part of a dynasty of caricaturists, their work often overlapped with Rowlandson's in subject matter, though George later developed a more distinct Victorian style.

Henry William Bunbury (1750-1811): An amateur artist whose humorous social caricatures were highly popular and influenced Rowlandson's gentler, less political style.

Richard Newton (1777-1798): A precocious talent who produced bold and often radical satires before his early death.

Augustus Charles Pugin (1762-1832): The architect with whom Rowlandson collaborated on The Microcosm of London.

George Morland (1763-1804): Rowlandson's friend, known for his sentimental paintings of rural life and animals, offering a contrast to Rowlandson's satirical focus.

John Raphael Smith (1751-1812): A leading mezzotint engraver who sometimes reproduced works by Rowlandson and others.

Paul Sandby (1731-1809): A key figure in English watercolour painting, known for his topographical landscapes, representing a different, more formal approach compared to Rowlandson's picturesque style.

Francisco Goya (1746-1828): A Spanish contemporary whose satirical prints (Los Caprichos) offered a darker, more psychologically probing critique of society, providing an interesting international comparison.

Honoré Daumier (1808-1879): A later French artist who carried the tradition of social and political caricature into the mid-19th century, often compared to the English masters.

Rowlandson's unique contribution within this context was his combination of high artistic skill (particularly in drawing and watercolour) with broad social observation and a generally good-humoured, if sometimes coarse, satirical eye.

Legacy and Influence

Thomas Rowlandson enjoyed considerable popularity during his lifetime, his prints eagerly consumed by a public fascinated by social commentary and humour. However, his reputation suffered a decline during the more prudish Victorian era, when the perceived vulgarity and frankness of his work fell out of favour. A reassessment began in the late 19th and early 20th centuries, recognizing his artistic merits and his invaluable role as a visual historian of the Georgian age.

Today, Rowlandson is acknowledged as a major figure in British art. His drawings and watercolours are prized for their technical brilliance and vitality, while his prints are studied for their rich depiction of social customs, class interactions, and the sheer energy of the period. He influenced subsequent generations of illustrators and caricaturists. His work provides an essential visual counterpoint to the literature and official histories of the time, offering intimate, often irreverent glimpses into the lives of people from all social strata.

His works are held in major public collections worldwide, including the British Museum, the Victoria and Albert Museum, the Tate Britain, the National Gallery of Art (Washington D.C.), the Metropolitan Museum of Art (New York), the Yale Center for British Art, and the Hood Museum of Art at Dartmouth College, among many others. They continue to be exhibited, studied, and enjoyed for their artistic skill and enduring satirical humour.

Conclusion

Thomas Rowlandson was far more than just a caricaturist. He was a versatile and highly accomplished artist whose work captured the spirit of Georgian England with unparalleled verve and insight. Through thousands of drawings, watercolours, and prints, he documented the social landscape of his time, from elegant drawing rooms to boisterous taverns, from picturesque countryside to the bustling streets of London. His fluid line, keen observation, and robust humour created a vivid, enduring panorama of human life in all its complexity, absurdity, and vitality. As both an artist and a social commentator, Rowlandson remains a key figure for understanding the visual culture and social history of the late 18th and early 19th centuries.