Emmanuel Gondouin stands as a notable, if sometimes overlooked, figure in the vibrant tapestry of early 20th-century French art. Born in Paris in 1883 and passing away in 1934, his relatively short life coincided with a period of radical artistic experimentation. Gondouin navigated these currents, initially engaging with Cubism before forging a path that, while informed by modernist principles, retained a strong connection to figurative representation, particularly in his landscapes and still lifes. His career, marked by both artistic exploration and personal hardship, offers a compelling glimpse into the challenges and triumphs of an artist working in one of art history's most dynamic eras.

Early Artistic Inclinations and Self-Directed Learning

Born into the bustling artistic heart of Paris, Emmanuel Gondouin's path to becoming a painter was not one paved through traditional academic institutions. Unlike many of his contemporaries who might have sought formal training at the prestigious École des Beaux-Arts, Gondouin appears to have cultivated his artistic talents through a more independent, self-directed approach. This avoidance of established art academies was not uncommon among artists seeking new modes of expression, who often found the conservative teachings of such institutions stifling to their innovative ambitions.

His decision to dedicate himself fully to painting crystallized around 1921. This was a significant year for him, marking not only a commitment to his vocation but also his first major public appearance within the avant-garde circles of Paris. It suggests a period of intense private development leading up to this point, where he honed his skills and artistic vision largely outside the formal structures of art education. This reliance on personal study and immersion in the artistic environment of Paris likely fostered a unique perspective, allowing him to absorb diverse influences and synthesize them in his own distinct manner.

Immersion in the Cubist Milieu

The year 1921 was a watershed moment for Emmanuel Gondouin, as it marked his formal entry into the Parisian art scene through his participation in a significant Cubist exhibition. In this show, he presented an impressive collection of over fifty works, a testament to his prolific output and his engagement with the principles of Cubism. This movement, pioneered by Pablo Picasso and Georges Braque around 1907, had revolutionized European painting by rejecting traditional notions of perspective and representation, instead opting for fragmented forms, multiple viewpoints, and a flattened picture plane.

By the early 1920s, Cubism had evolved and diversified. Key figures like Juan Gris had brought a more systematic and colorful approach, while artists such as Albert Gleizes and Jean Metzinger, authors of the influential treatise Du "Cubisme" (1912), were central to a broader group of Cubists, often referred to as the Salon Cubists or Section d'Or group. This group also included artists like Fernand Léger, with his distinctive "Tubist" style, and Robert Delaunay, who, with his wife Sonia Delaunay, developed Orphism, a more abstract and colorful offshoot of Cubism. Gondouin's involvement in a Cubist exhibition placed him directly within this dynamic and evolving avant-garde landscape. His exploration of Cubist tenets, even if it later gave way to other stylistic concerns, was a crucial phase in his artistic development, equipping him with a modern understanding of form, space, and composition.

Stylistic Evolution: From Cubist Exploration to Figuration

While Gondouin's early career saw a significant engagement with Cubism, his artistic trajectory did not remain fixed within its more radical expressions. He explored various stylistic avenues, sometimes approaching the analytical or synthetic phases of Cubism, but ultimately, his oeuvre demonstrates a strong inclination towards more figurative representation, particularly in his landscapes and still life paintings. This evolution suggests an artist who absorbed the lessons of modernism but sought to integrate them with a more personal and perhaps traditional appreciation for the observable world.

An influential figure in this regard appears to have been André Lhote, a painter and theorist who himself navigated a path between Cubism and a more ordered, classical figuration. Lhote's teachings and example encouraged a structured, geometric approach to composition while retaining recognizable subject matter. Gondouin’s tendency towards more representational landscapes, likely imbued with a Cubist-informed sense of structure and simplification, aligns with Lhote's influence. Despite his explorations of abstraction, Gondouin maintained a certain "loyalty to realism," as some observations suggest, indicating a desire to ground his artistic vision in tangible reality, albeit filtered through a modernist lens. His diverse output, therefore, reflects a nuanced dialogue between avant-garde innovation and a persistent connection to the representational traditions of painting.

Representative Works: A Glimpse into Gondouin's Artistry

Emmanuel Gondouin's body of work, though perhaps not as widely known as some of his more famous contemporaries, includes a variety of subjects and styles that highlight his artistic concerns. Among his notable pieces are still lifes, portraits, and landscapes, each reflecting different facets of his engagement with early 20th-century artistic currents.

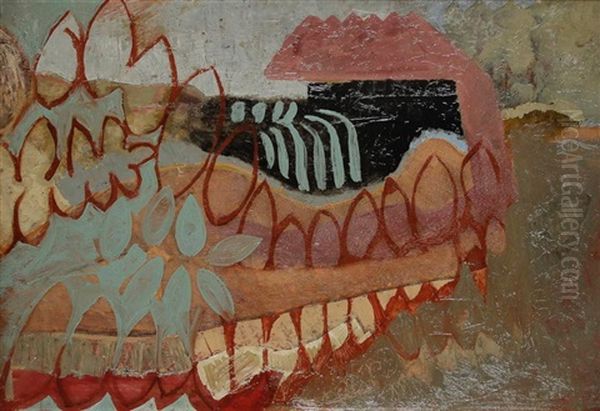

Nature morte à la table (Still Life on the Table), sometimes referred to as Table of Natural Death and dated between 1927-1930, exemplifies his work in the still life genre. Such compositions would have allowed him to explore formal arrangements, the interplay of objects, and the application of Cubist-derived principles to everyday items. The very act of painting a still life connects him to a long tradition, from Dutch Golden Age masters to Post-Impressionists like Paul Cézanne, whose structural approach to still life was a profound influence on Cubism itself.

His portraiture, such as Portrait de femme (Woman's Portrait) from 1918 and Femme à la collier de perle (Woman with a Pearl Necklace), suggests an interest in capturing human likeness, potentially filtered through a modern sensibility. The work titled Portrait cubisant (Cubist Portrait) explicitly points to his experiments with the Cubist idiom in depicting the human form, likely involving faceted planes and a departure from traditional anatomical rendering, akin to early portraits by Picasso or Braque. Another piece, Nu cubiste (Cubist Nude), further underscores this exploration.

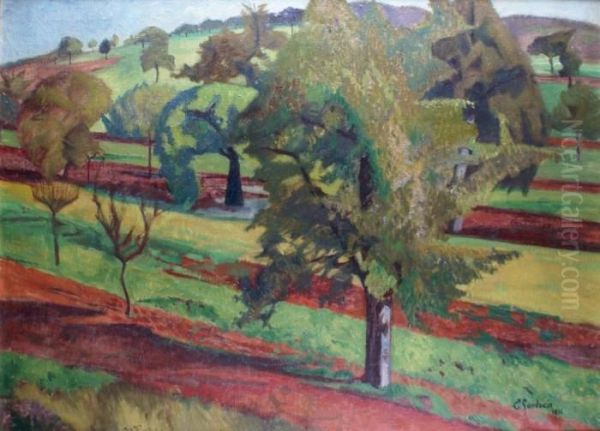

Landscapes formed a significant part of his output. Works like Paysage campagnard arboré (Wooded Country Landscape), Le Verger (The Orchard), and Étude de feuillages (Study of Foliage) indicate a deep engagement with nature. These pieces likely combined observational detail with a structured, perhaps geometrically simplified, approach to form, reflecting the influence of artists like Cézanne and the more figurative tendencies within the broader Cubist movement. Other works, such as Bouquet de fleurs (Bouquet of Flowers), showcase his handling of color and form in a more decorative context, often executed in watercolor and crayon, demonstrating his versatility across different media.

Connections and Collaborations in the Parisian Art World

Emmanuel Gondouin was not an isolated figure; he was part of the vibrant and interconnected art world of Paris. His interactions with fellow artists and participation in collective projects provide insight into his place within this community. A significant connection was with Albert Gleizes, one of the leading theorists and practitioners of Cubism. Gondouin is documented as having assisted Gleizes with plans for his house in Cavaire, suggesting a working relationship that extended beyond purely artistic discussions into practical, perhaps even decorative or architectural, applications of artistic principles. This collaboration indicates a level of trust and mutual respect between the two artists.

Furthermore, Gondouin was involved in the ambitious "Ideal Artists' Village" project initiated by Robert Delaunay in 1929. This visionary project aimed to create a dedicated community for artists, complete with studios, residences, and other facilities, fostering a collaborative and supportive environment. Gondouin's participation alongside other prominent artists such as Jean Arp, a key figure in Dada and Surrealism, and Marc Chagall, known for his uniquely poetic and dreamlike imagery, places him within a circle of forward-thinking individuals. The project also reportedly involved René d'Harnoncourt, who would later become an influential museum director. Such initiatives highlight the utopian and communal aspirations prevalent among certain avant-garde circles of the time.

His name also appears in contexts alongside other major figures of the era. Mentions of his work in relation to that of Georges Braque and Pablo Picasso, the titans of Cubism, or Juan Gris, underscore his association with this pivotal movement. The Parisian art scene was a melting pot, and artists often knew each other, exhibited together, or were discussed in relation to one another by critics and collectors. This network of relationships, exhibitions, and shared artistic dialogues was crucial for the development and dissemination of new artistic ideas.

The Parisian Art Scene: A Crucible of Modernism

To fully appreciate Emmanuel Gondouin's career, it is essential to consider the extraordinary artistic environment of Paris in the early 20th century. The city was an unparalleled magnet for artists from across Europe and beyond, a crucible where traditional artistic conventions were being challenged and overthrown with breathtaking speed. Movements like Fauvism, with its explosive use of color championed by artists such as Henri Matisse and André Derain, had already shocked the establishment before Cubism emerged.

The atmosphere was one of constant debate, experimentation, and the formation of new artistic groups and manifestos. Salons, galleries, and cafés buzzed with discussions about the future of art. Artists like Amedeo Modigliani, with his distinctive elongated portraits and nudes, and Chaim Soutine, whose expressive and turbulent works captured a raw emotional intensity, were also part of this milieu, each forging unique paths. The city's landscape itself was a subject for artists like Maurice Utrillo, who depicted the streets of Montmartre with a melancholic poetry.

Gondouin's decision to pursue art in this environment meant immersing himself in a world of intense competition but also immense creative stimulus. His participation in Cubist exhibitions and his collaborations with figures like Gleizes and Delaunay demonstrate his active engagement with the avant-garde. However, the economic realities for artists, especially those not achieving widespread fame or consistent patronage, could be harsh. The bohemian lifestyle, while often romanticized, frequently involved financial precarity.

Later Years, Economic Hardship, and Posthumous Recognition

The later period of Emmanuel Gondouin's life was marked by significant personal challenges, most notably severe economic hardship. Despite his talent and active participation in the art world, he faced the grim reality of poverty, a plight shared by many artists of his time who struggled for recognition and financial stability. Tragically, it is reported that Gondouin died from starvation in 1934, a stark testament to the difficulties he endured. This occurred before his work began to be more widely exhibited by galleries, suggesting that broader recognition came too late to alleviate his personal suffering.

However, his artistic contributions did not go entirely unnoticed. A year after his death, in 1935, a retrospective exhibition of his work was held at the prestigious Galerie Druet in Paris. Such posthumous exhibitions often serve to re-evaluate an artist's oeuvre and secure their place in art historical narratives. The fact that a gallery of Druet's standing organized this show indicates a recognition of his merit within artistic circles.

In the decades that followed, Gondouin's works have continued to surface, appearing in auctions and finding their way into private collections. For instance, his paintings have been noted in sales at Drouot-Richelieu and the Boisgirard Auction House. The inclusion of his art in esteemed private collections, such as that of Marella Agnelli at the Villar Perosa estate in Italy, where one of his paintings adorned the library designed in the 1950s, and in the home of Madame Catroux, further attests to a lasting appreciation for his work among discerning collectors. These instances of posthumous recognition, while unable to change the tragic circumstances of his life, ensure that Emmanuel Gondouin's artistic voice continues to be heard.

Legacy and Artistic Contribution

Emmanuel Gondouin's legacy is that of an artist who earnestly engaged with the transformative currents of early 20th-century modernism, particularly Cubism, while ultimately charting a course that retained a strong connection to figurative art. He represents a cohort of artists who, while not achieving the household-name status of figures like Picasso or Matisse, contributed significantly to the richness and diversity of the Parisian art scene. His willingness to explore different styles, from the analytical rigor of Cubism to the more lyrical representation of landscapes and still lifes, speaks to a versatile and searching artistic temperament.

His association with key Cubist figures like Albert Gleizes and his participation in avant-garde projects like Robert Delaunay's "Ideal Artists' Village" highlight his active role within the artistic community. The influence of André Lhote, steering him towards a more structured yet representational approach, is also a key aspect of his development, placing him within a lineage of artists seeking to reconcile modernist innovations with enduring pictorial traditions.

The tragic circumstances of his death in poverty underscore the precarious existence of many artists, even those of considerable talent. However, the posthumous exhibitions and the continued presence of his works in auctions and private collections demonstrate a sustained, if modest, recognition of his artistic merit. He serves as a reminder that the art historical narrative is composed not only of its most celebrated protagonists but also of many other dedicated individuals whose work contributes to the broader understanding of an era. Gondouin's art, bridging Cubist experimentation and a lasting affinity for the visible world, offers a valuable perspective on the complex artistic dialogues of his time.

Conclusion: An Enduring Artistic Voice

Emmanuel Gondouin's life and career offer a compelling narrative of artistic dedication in the face of adversity. Active during a period of profound artistic upheaval in Paris, he absorbed the revolutionary principles of Cubism and engaged with its leading proponents. Yet, he also forged a personal style that, while modern, remained rooted in the observation of reality, particularly evident in his landscapes and still lifes. His collaborations with artists like Albert Gleizes and his involvement in visionary projects reflect his integration within the avant-garde community.

Though his life was cut short by hardship, the posthumous recognition of his work, through exhibitions and its inclusion in notable collections, affirms his contribution to French art. Emmanuel Gondouin may not be among the most widely celebrated names of his generation, but his art provides a nuanced insight into the diverse responses to modernism, embodying a thoughtful synthesis of innovation and tradition. His story is a poignant reminder of the passion, struggle, and enduring creativity that characterize the artistic endeavor.