Domenico Maria Canuti stands as a significant, if sometimes underappreciated, figure in the vibrant landscape of Italian Baroque painting. Born in Bologna, a city renowned for its rich artistic heritage, Canuti carved out a distinguished career, primarily as a painter of large-scale frescoes that adorned the ceilings and walls of palaces and churches. His life, spanning from approximately 1620 to 1683, saw him navigate the complex artistic currents of his time, absorbing influences from Bolognese classicism and Roman High Baroque dynamism to forge a powerful and expressive personal style. While the exact dates of his birth and death have been subject to some scholarly debate, with alternative suggestions of 1626 for his birth and 1684 for his death, the consensus leans towards the earlier timeframe.

Early Life and Artistic Formation in Bologna

Domenico Maria Canuti’s artistic journey began in Bologna, a city that, since the late 16th century, had been a crucible of artistic innovation, largely thanks to the reforms initiated by the Carracci family – Ludovico, Agostino, and Annibale Carracci. Their Accademia degli Incamminati had established a new direction for art, emphasizing drawing from life, a return to High Renaissance principles, and a clear, direct narrative style. By the time Canuti was embarking on his training, Bologna was home to a new generation of masters who had built upon the Carracci legacy.

Canuti was fortunate to receive instruction from some of the leading painters of the Bolognese school. His formative years were spent in the workshops of Guido Reni, one of the most celebrated Italian painters of the era, known for his elegant classicism, refined figures, and delicate palette. From Reni, Canuti would have absorbed a strong sense of composition, a grace in figural representation, and a commitment to idealized beauty.

He also trained with Giovanni Francesco Barbieri, famously known as Guercino. Guercino’s style, particularly in his earlier period, was characterized by robust naturalism, dramatic chiaroscuro, and a profound emotional intensity. This exposure would have provided Canuti with a contrasting, yet equally vital, artistic vocabulary, emphasizing dynamism and painterly richness.

A third significant master in Canuti's early development was Giovanni Andrea Sirani. A faithful pupil of Guido Reni, Sirani was a respected painter in his own right and would have reinforced the classical tenets of Reni's studio. Sirani was also the father of the gifted painter Elisabetta Sirani, a contemporary of Canuti who achieved considerable fame before her untimely death. The artistic environment in Bologna was thus rich and varied, offering young artists like Canuti a broad spectrum of stylistic approaches.

First Roman Sojourn and Developing Style

In the 1640s, like many ambitious artists of his generation, Canuti made his way to Rome. The papal city was the undisputed center of the art world, a place where artists could study classical antiquities, marvel at the masterpieces of the High Renaissance, and engage with the latest developments in Baroque art. During this period, Rome was dominated by figures such as Gian Lorenzo Bernini in sculpture and architecture, and Pietro da Cortona and Andrea Sacchi in painting.

Pietro da Cortona, in particular, was revolutionizing ceiling fresco painting with his exuberant, illusionistic, and overwhelmingly grand compositions, such as the ceiling of the Gran Salone in the Palazzo Barberini. The influence of Cortona's dynamic figures, swirling compositions, and vibrant colorism is discernible in Canuti's subsequent work. He also would have studied the more classically inclined Baroque style of Annibale Carracci, whose Farnese Gallery frescoes remained a benchmark for monumental decorative schemes. The influence of Francesco Gessi, another Bolognese painter active in Rome and Naples, is also noted during this formative Roman stay.

One of Canuti's notable early works from this Roman period, or shortly thereafter, reflecting these burgeoning influences, is The Essay of Saint Cecilia (or The Trial of Saint Cecilia), a subject he would revisit. This work likely demonstrated his growing confidence in handling complex multi-figure compositions and his assimilation of Roman grandeur.

Return to Bologna and the Paduan Interlude

After his initial Roman experience, Canuti returned to his native Bologna, where his career began to flourish. He received significant commissions for both easel paintings and, increasingly, large-scale frescoes. His reputation as a skilled decorator grew, particularly for his ability to create expansive, illusionistic ceiling paintings that seemed to open up the architecture to the heavens.

During the 1660s, Canuti spent a period working in Padua. While details of his Paduan activities are somewhat less documented, it is known that he undertook commissions there. One notable, though perhaps problematic, project mentioned in some sources involves frescoes for a Palazzo Pepoli in Padua, which were reportedly left unfinished. This highlights the complexities and sometimes uncertain outcomes of large-scale artistic undertakings in the period.

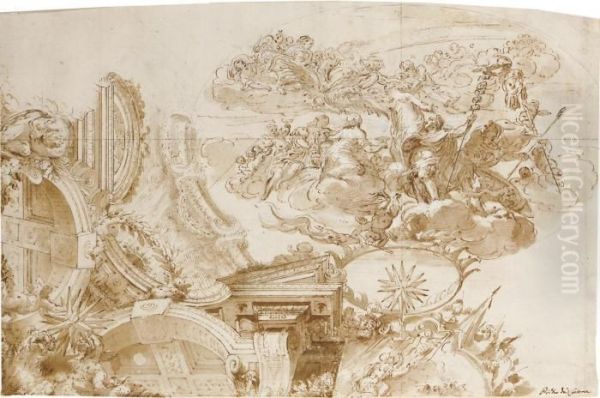

His primary base, however, remained Bologna. It was here that he executed one of his most celebrated works: the ceiling frescoes in the Palazzo Pepoli Campogrande. The main salon features the spectacular Apotheosis of Hercules, a tour-de-force of Baroque illusionism. In this work, Canuti masterfully employed sotto in sù (seen from below) perspective, creating a dizzying vision of Hercules being welcomed into the Olympian pantheon. The figures are muscular and dynamic, swirling amidst clouds and architectural vistas. Such works often involved collaboration with quadratura specialists, painters who excelled in creating illusionistic architectural frameworks. Figures like Domenico Santi, known as Mengazzino, or members of the Haffner family, such as Enrico Haffner, were renowned for this specialized skill in Bologna and often worked alongside figure painters like Canuti.

Another significant Bolognese commission was the altarpiece of The Ecstasy of Saint Cecilia for the church of Santa Cecilia in Imola, a town near Bologna. This work showcases his ability to convey intense religious emotion through dynamic composition and rich color.

Second Roman Period and Major Fresco Cycles

The 1670s saw Canuti return to Rome for a second extended stay. By this time, he was an established master, and he secured prestigious commissions that further solidified his reputation. One of the most important was the decoration of the ceiling of the church of Santi Domenico e Sisto. Here, he painted the Apotheosis of Saint Dominic, another vast and complex celestial vision. This work placed him in direct comparison with other leading fresco painters active in Rome, such as Baciccio (Giovanni Battista Gaulli), who was concurrently working on the spectacular ceiling of the Gesù.

Canuti's work at Santi Domenico e Sisto demonstrated his full command of the High Baroque idiom, characterized by its dramatic energy, illusionistic depth, and vibrant palette. He skillfully managed the vast surface, populating it with a multitude of figures that spiral upwards towards a divine light, creating a powerful sense of movement and spiritual transcendence.

During this Roman period, he also contributed to the decoration of the Palazzo Altieri, a prominent Roman palace. For the Altieri family, whose member Emilio Altieri had become Pope Clement X in 1670, Canuti painted the Apotheosis of Romulus. This subject, drawn from Roman mythology, was a fitting theme for a powerful Roman family and allowed Canuti to display his erudition and his skill in depicting heroic, classical narratives within a dynamic Baroque framework. His work at Palazzo Altieri placed him alongside other notable artists commissioned by the family, including Carlo Maratta, who was a dominant figure in Roman painting at the time, championing a more classical and restrained version of the Baroque.

Canuti's activity in Rome also led to his membership in the prestigious Accademia di San Luca, the official artists' academy in Rome. This was a mark of recognition from his peers and confirmed his standing within the Roman artistic establishment.

Later Bolognese Works and Continued Activity

Following his successful second period in Rome, Canuti returned once more to Bologna, where he remained a leading artistic figure until his death. He continued to receive important commissions for churches and private patrons.

Among his significant later works in Bologna are the frescoes in the library of the monastery of San Michele in Bosco. Here, he painted an Allegory of Divine and Human Wisdom, a complex allegorical program suited to the intellectual environment of a monastic library. These frescoes demonstrate his continued mastery of large-scale decorative schemes and his ability to translate abstract concepts into compelling visual narratives.

Another major late project was the decoration of the Certosa di San Girolamo in Bologna. For the Carthusian monastery, he painted a powerful Final Judgment. This work is particularly interesting as it is associated with an anecdote regarding its later condition. It was reported in the 18th century that the colors of the Final Judgment had darkened considerably over time, a change attributed by some to Canuti's alleged carelessness in the preparation of the canvas or wall surface. Whether this was due to specific technical choices, the inherent instability of certain pigments, or later environmental factors, it points to the material challenges faced by artists and the subsequent transformations their works could undergo.

Throughout his career, Canuti also produced numerous easel paintings, including religious subjects, mythological scenes, and portraits, though he is primarily celebrated for his monumental fresco cycles.

Artistic Style, Techniques, and Influences

Domenico Maria Canuti’s artistic style is a compelling synthesis of various influences, forged into a distinctive personal idiom. At its core, his art is rooted in the Bolognese tradition, with its emphasis on strong drawing, clear composition, and often, a certain classical restraint inherited from the Carracci and Guido Reni.

However, Canuti infused this Bolognese foundation with the dynamism and grandeur of the Roman High Baroque, particularly the style of Pietro da Cortona. This is evident in his swirling compositions, his use of dramatic foreshortening (sotto in sù), and the sheer energy that animates his figures. He excelled in creating illusionistic spaces that seem to extend beyond the confines of the actual architecture, drawing the viewer into the painted scene.

His use of color was rich and vibrant, sometimes showing a Venetian sensibility, but always controlled and used to enhance the narrative and emotional impact of his work. He was a master of chiaroscuro, employing strong contrasts of light and shadow to model his figures, create dramatic effects, and guide the viewer's eye through complex compositions. This skill was likely honed through his study of Guercino.

Canuti developed a distinctive "painterly language," especially evident in his ceiling frescoes. He was adept at organizing vast numbers of figures into coherent and dynamic groups, creating a sense of awe-inspiring spectacle. While influenced by Annibale Carracci and Pietro da Cortona, he was not merely an imitator but adapted their innovations to his own expressive ends. His figures are often robust and muscular, conveying a sense of power and vitality.

His technical proficiency in the demanding medium of fresco was considerable. Buon fresco, painting on fresh, wet plaster, required speed, confidence, and meticulous planning, as mistakes were difficult to correct. Canuti's large-scale works attest to his mastery of this technique.

Relationships with Contemporaries: Teachers, Students, and Collaborators

Canuti’s career was interwoven with the lives and works of many other artists. His training under Guido Reni, Guercino, and Giovanni Andrea Sirani provided him with a foundational network and diverse stylistic impulses.

He, in turn, became a teacher, passing on his knowledge and skills to a new generation. Among his most notable pupils was Giuseppe Maria Crespi, one of the most original and important Bolognese painters of the late Baroque and early Rococo. Crespi, known for his genre scenes, religious paintings, and portraits, developed a highly individual style characterized by its expressive brushwork and dramatic lighting, but his early training with Canuti would have provided him with a solid grounding in Baroque composition and technique. Another student mentioned is Giuseppe Maria Rolli, who also became a respected painter.

Canuti also engaged in collaborations. As mentioned, large-scale fresco projects often involved specialists in quadratura. He is also documented as having collaborated or had professional interactions with Carlo Cignani, a leading Bolognese painter of the same generation. Cignani, whose style was generally more classical and graceful, was a dominant figure in Bologna, and their careers often ran parallel. One account mentions Canuti and Cignani participating in life drawing sessions at the Favi family workshop, indicating a shared commitment to academic practice.

In Rome, Canuti would have been aware of, and in some ways competed with, prominent artists like Carlo Maratta and Baciccio. Maratta, in particular, represented a more classicizing trend in Roman Baroque painting, and his influence was immense. Canuti’s more exuberant and painterly style offered an alternative, aligning more closely with the High Baroque tradition of Cortona.

The artistic landscape of Bologna during Canuti's lifetime also included other notable figures such as Lorenzo Pasinelli, another significant painter and teacher, and the aforementioned Elisabetta Sirani, whose talent shone brightly. These interactions, whether as teacher, student, collaborator, or competitor, shaped Canuti's career and his place within the artistic ecosystem of his time.

Legacy and Art Historical Position

Domenico Maria Canuti holds a secure place as a major exponent of Baroque ceiling decoration, particularly within the Bolognese school. His ability to synthesize the classical traditions of Bologna with the dynamic energy of Roman High Baroque resulted in works of considerable power and visual impact. He was a key figure in continuing Bologna's reputation as a center for monumental fresco painting.

Despite his achievements, Canuti's fame has, at times, been somewhat overshadowed by his more celebrated teachers like Reni and Guercino, or by Roman contemporaries like Cortona or Maratta. This is not uncommon for artists who, while highly successful and respected in their own time, may not have achieved the same level of posthumous canonical status as a select few.

His works were considered competitive in the demanding Roman art market, yet some critics, then and later, may have perceived his style as retaining a distinctly "Bolognese" character, perhaps seen as less aligned with the prevailing Roman taste at certain moments. However, this very "Bolognese-ness," with its emphasis on solid draughtsmanship and narrative clarity, combined with his adopted Roman grandeur, is what defines his unique contribution.

He played an important role in the transmission of artistic knowledge through his teaching, most notably influencing Giuseppe Maria Crespi, who would go on to become a highly innovative artist. Canuti's frescoes, particularly those in Bologna like the Palazzo Pepoli Campogrande and San Michele in Bosco, remain important testaments to the vitality of the Bolognese school in the latter half of the 17th century.

Anecdotes and Unresolved Aspects

Several intriguing details and minor mysteries surround Canuti's life and work, adding layers to his biography. The aforementioned color change in his Final Judgment at the Certosa, attributed to his preparatory methods, raises questions about his specific techniques and material choices. Such stories, common in the biographies of artists, often blend fact with later interpretation.

His stylistic evolution, showing a capacity to absorb and adapt contemporary Roman trends while retaining his Bolognese roots, is a fascinating aspect of his career. This adaptability was crucial for an artist seeking major commissions in different artistic centers.

The report of his involvement with Carlo Cignani in nude drawing classes at the Favi studio suggests a commitment to the academic foundations of art, even for an established master. It also hints at the collaborative and collegial, as well as competitive, nature of the art world.

The unfinished frescoes in Padua, if accurately attributed and reported, point to the practical challenges of artistic patronage and execution. Large commissions could be subject to changes in funding, patronal whim, or other unforeseen circumstances.

His choice of patrons and commissions, sometimes in less prominent venues or for patrons outside the absolute apex of fashion, might also be considered. While he worked for major families like the Altieri and Pepoli, and for important religious orders, the trajectory of his patronage offers insights into the career strategies available to artists of his caliber.

The extent of his technical innovations, particularly in the use of chiaroscuro and vibrant color in fresco, and their direct influence on subsequent artists beyond his immediate pupils, remains a subject for nuanced art historical assessment.

Conclusion

Domenico Maria Canuti was a highly skilled and productive painter who made significant contributions to Italian Baroque art, especially in the realm of monumental fresco decoration. Born and trained in the rich artistic milieu of Bologna, he absorbed the lessons of masters like Guido Reni and Guercino. His subsequent experiences in Rome exposed him to the grandeur of High Baroque painters like Pietro da Cortona, enabling him to forge a powerful style that combined Bolognese solidity with Roman dynamism.

His ceiling frescoes in palaces and churches, such as the Apotheosis of Hercules in Bologna's Palazzo Pepoli Campogrande and the Apotheosis of Saint Dominic in Rome's Santi Domenico e Sisto, are characterized by their energetic figures, illusionistic depth, and vibrant color. He was a master of creating breathtaking celestial visions that transformed architectural spaces.

While perhaps not as universally recognized today as some of his contemporaries, Canuti was a respected artist in his time, a member of the Accademia di San Luca, and a teacher who influenced important painters like Giuseppe Maria Crespi. His work stands as a testament to the enduring vitality of the Bolognese school and its significant role in the broader narrative of Italian Baroque art. His legacy endures in the magnificent frescoes that continue to adorn the buildings for which they were created, offering a vivid glimpse into the artistic ambitions and achievements of 17th-century Italy.