Antonio Allegri, known to the world as Correggio after his birthplace, stands as one of the most significant painters of the Italian High Renaissance. Though often associated with the Parma school, his unique style transcended regional boundaries, creating works renowned for their sensuous charm, masterful handling of light and shadow, and dynamic compositions that anticipated the drama of the Baroque era. Working somewhat outside the main artistic currents of Rome, Florence, and Venice, Correggio developed a deeply personal and influential artistic language.

His full name was Antonio Allegri, and he was born in the small town of Correggio, located in the Emilia-Romagna region of Northern Italy, not far from the city of Parma. This geographical origin would define his moniker and shape his career, as Parma became the primary center for his most ambitious works.

The Question of Dates

Pinpointing Correggio's exact birth and death dates requires careful consideration of historical records. While some minor debate has existed, the consensus among art historians points to his birth occurring in August 1489. Earlier suggestions, such as 1494, lack substantial supporting evidence compared to the documentation favouring 1489.

His life, marked by intense artistic production, came to a close relatively early. Historical records confirm that Antonio Allegri da Correggio died in his hometown on March 5, 1534. This places his lifespan firmly within the vibrant period of the High Renaissance, making him a contemporary, albeit slightly younger or geographically distinct, of giants like Leonardo da Vinci, Raphael, and Michelangelo.

Early Life and Artistic Formation

Details about Correggio's earliest training remain somewhat scarce, a common issue for artists of this period outside major metropolitan centers. It is believed his uncle, Lorenzo Allegri, may have provided some initial instruction. More concrete evidence suggests a period of study in Modena, possibly under Francesco Bianchi Ferrara.

This formative period exposed the young Correggio to influential artistic currents. The works of Andrea Mantegna, a master of perspective and sculptural form active in nearby Mantua, undoubtedly left a mark. Similarly, the softer, more atmospheric qualities found in the paintings of Lorenzo Costa, active in Bologna and Mantua, likely contributed to Correggio's developing style. Crucially, the pervasive influence of Leonardo da Vinci, particularly his pioneering use of sfumato (soft, hazy transitions between colours and tones), seems evident in Correggio's later handling of light and emotion.

Correggio's Distinctive Style: Light and Shadow

One of the defining characteristics of Correggio's art is his extraordinary mastery of light and shadow, or chiaroscuro. He moved beyond the starker contrasts sometimes employed by earlier artists, developing a technique characterized by soft, luminous transitions. Light in his paintings often appears to emanate from within the figures or from a divine source, bathing scenes in a warm, ethereal glow.

This sophisticated handling of light serves multiple purposes. It creates a powerful sense of volume and three-dimensionality, making his figures feel tangible and present. More importantly, it enhances the emotional resonance of his work. Gentle light can convey tenderness and intimacy, while dramatic contrasts can heighten spiritual ecstasy or poignant sorrow. His chiaroscuro is less about sharp lines and more about a pervasive, unifying atmosphere, contributing significantly to the sensuous appeal of his art.

Compositional Innovation and Illusionism

Correggio was a bold innovator in composition and perspective. He broke free from the often static, symmetrical arrangements favoured by some High Renaissance classicists. His compositions are frequently dynamic, employing diagonal lines and swirling movements that guide the viewer's eye through the scene. Figures are arranged in complex, overlapping groups, creating a sense of depth and energy.

His most revolutionary contribution in this area was his pioneering use of illusionistic ceiling painting, particularly the technique known as sotto in sù (meaning "from below, upward"). In his dome frescoes, he painted figures as if seen from directly below, creating the breathtaking illusion that the ceiling has opened up to the heavens. This radical approach to perspective creates a powerful sense of verticality and spiritual uplift, directly paving the way for the spectacular ceiling decorations of the Baroque period.

Emotional Depth and Sensuous Appeal

Correggio's art is imbued with a unique blend of emotional depth and sensuous beauty. His figures, whether divine or mythological, possess a remarkable tenderness and grace. Madonnas gaze upon the Christ child with palpable maternal love, saints experience moments of spiritual rapture that feel both human and transcendent, and mythological figures express passion and vulnerability.

This emotional accessibility is coupled with a distinct sensuousness. Correggio rendered flesh tones with a soft, pearly quality (morbidezza) that feels almost palpable. His figures often have gentle smiles, slightly parted lips, and languid poses that contribute to an atmosphere of sweetness and charm. This quality, while rooted in Renaissance humanism, anticipates the lighter, more overtly decorative sensibilities of the later Rococo period.

Masterworks in Parma: The Camera di San Paolo

Correggio's arrival in Parma marked the beginning of his mature period and led to the creation of his most celebrated works. One of his earliest major commissions in the city (around 1519) was the decoration of the abbess's private dining room in the Benedictine convent of San Paolo.

Known as the Camera di San Paolo, the ceiling fresco is a delightful display of Correggio's burgeoning skill in illusionism and his charming interpretation of classical themes. He transformed the umbrella-vaulted ceiling into an illusionistic trellis or arbour, seemingly open to the sky. Playful putti (cherubs) peek through oval openings, framed by lush garlands of fruit and foliage. Below, lunettes feature monochrome depictions of mythological subjects, possibly alluding to the virtues or intellectual pursuits of the abbess, Giovanna Piacenza. The overall effect is one of sophisticated whimsy and masterful spatial deception.

Masterworks in Parma: San Giovanni Evangelista

Following the success at San Paolo, Correggio received commissions for the church of San Giovanni Evangelista in Parma. Here, he undertook even more ambitious fresco projects between approximately 1520 and 1524.

His most stunning achievement in this church is the fresco decorating the interior of the main dome: the Vision of St. John on Patmos. This work represents a significant leap forward in his use of sotto in sù. Christ is depicted ascending into heaven, surrounded by a swirling vortex of apostles seated on clouds. The figures are dramatically foreshortened, creating a powerful illusion of looking directly up into the heavens. The dynamic energy and overwhelming scale of the composition were revolutionary for their time.

Correggio also painted other significant works for San Giovanni Evangelista, including frescoes in the apse (later damaged) and powerful panel paintings like the Lamentation (or Deposition), notable for its intense emotional portrayal of grief and its sophisticated use of light to focus the drama.

The Pinnacle: Parma Cathedral's Dome

Correggio's ultimate masterpiece of illusionistic ceiling painting is the Assumption of the Virgin in the dome of Parma Cathedral, executed between roughly 1526 and 1530. This vast fresco represents the culmination of his experiments with perspective and dynamic composition.

The Virgin Mary is carried aloft on swirling clouds, surrounded by an ecstatic multitude of angels, saints, and biblical figures. The entire dome becomes a celestial vortex, drawing the viewer upwards into the divine event. Correggio masterfully organizes the immense number of figures into a coherent, spiraling composition, using light, colour, and dramatic foreshortening to create an unparalleled sense of movement and spiritual transport. The sheer audacity and technical brilliance of the Assumption cemented Correggio's reputation and served as a foundational work for Baroque ceiling painters like Giovanni Lanfranco and Pietro da Cortona.

Notable Panel Paintings

Beyond his monumental fresco cycles, Correggio was a prolific painter of panel paintings, creating altarpieces and private devotional works, as well as mythological scenes. These works further showcase his stylistic hallmarks.

The Adoration of the Shepherds (La Notte): Painted around 1529-1530 and now in Dresden, this work is famed for its innovative depiction of night. The divine light emanates powerfully from the Christ child, illuminating the Virgin's face and casting dramatic shadows on the surrounding figures. It's a masterful study in nocturnal chiaroscuro.

Madonna and Child with St. Jerome (Il Giorno): A counterpoint to La Notte, this painting (c. 1528, Parma) is bathed in bright daylight. It features a complex, dynamic composition and showcases Correggio's ability to render rich textures and convey tender interactions between the figures, including Mary Magdalene affectionately leaning against the Christ child.

Madonna della Scodella: This work (c. 1528-1530, Parma) depicts the Rest on the Flight into Egypt. It is noted for its gentle intimacy, harmonious composition, and the characteristic sweetness of the figures.

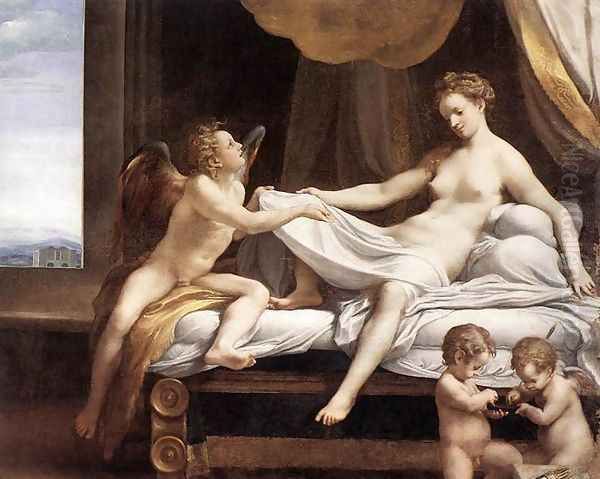

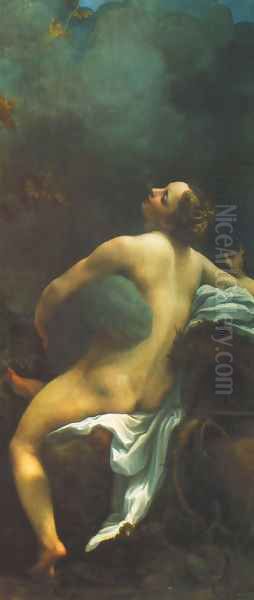

Mythological Series for Federico II Gonzaga: In the early 1530s, Correggio painted a series of sensuous mythological subjects, likely commissioned by the Duke of Mantua. These include Danaë (Rome), Leda and the Swan (Berlin), Jupiter and Io (Vienna), and The Abduction of Ganymede (Vienna). These works are celebrated for their erotic charge, graceful figures, and masterful rendering of flesh and atmosphere.

Other Important Works: Other significant panel paintings include the early Madonna and Child with the Young Saint John (c. 1515, Rome), the moving Noli me Tangere (c. 1525, Madrid), and the dramatic Martyrdom of Four Saints (c. 1524, Parma).

Connections with Contemporaries

While Correggio was undoubtedly aware of the work of the great masters of his time, documented evidence of direct personal interaction, particularly with figures like Raphael or Titian, is scarce. His career unfolded primarily in Parma and surrounding areas, somewhat removed from the central hubs of Rome and Venice where Raphael (until his death in 1520) and Titian were dominant figures.

However, the influence of Leonardo da Vinci, Andrea Mantegna, and Michelangelo is clearly discernible in his work. He absorbed Leonardo's sfumato and psychological depth, Mantegna's mastery of perspective and classical form, and Michelangelo's powerful figure drawing, particularly evident in the muscular apostles of the San Giovanni Evangelista dome. While some scholars note stylistic contrasts, such as the difference in feeling between Correggio's Madonnas and those of Raphael, this reflects Correggio's unique artistic personality rather than documented collaboration or direct rivalry. His most direct artistic heir in Parma was Parmigianino, who absorbed and further developed aspects of Correggio's elegant style.

Later Years and Death

After completing his major works in Parma, including the Cathedral dome around 1530, Correggio eventually returned to his hometown. Sources suggest he lived a relatively modest and pious life in Correggio during his final years, continuing to paint but perhaps on a less monumental scale.

He died there on March 5, 1534, at the age of about 44 or 45. The art historian Giorgio Vasari later recounted a story that Correggio died from exhaustion after carrying a large payment in copper coins over a long distance in hot weather, but this anecdote is generally considered apocryphal and likely intended to portray the artist as poorly treated or overly concerned with money. His relatively early death cut short a career that was still evolving.

Legacy and Enduring Influence

Correggio's influence on the course of European art was profound, even if his full recognition was somewhat delayed compared to the Florentine and Roman masters. His innovations directly paved the way for the Baroque style that would dominate the 17th century.

Baroque Illusionism: His dome frescoes in Parma were revolutionary. The sotto in sù perspective and the creation of dynamic, heavenly visions became standard practice for Baroque ceiling painters like Giovanni Lanfranco, Pietro da Cortona, and Andrea Pozzo.

Light and Emotion: His masterful use of chiaroscuro and his ability to convey intense emotion – from tender intimacy to spiritual ecstasy – deeply influenced Baroque artists who sought heightened drama and psychological depth. Figures like Caravaggio, with his dramatic tenebrism, and Rembrandt, with his empathetic use of light, owe a debt to Correggio's explorations. The sculptors of the Baroque, notably Gian Lorenzo Bernini, also captured a similar intensity of emotion and movement that resonates with Correggio's painted figures.

Sensuousness and Movement: The grace, softness, and dynamic movement in Correggio's figures found echoes in the works of Peter Paul Rubens, whose canvases pulse with similar energy and sensuous appeal. The Carracci family (Annibale, Agostino, and Ludovico), founders of the Bolognese academy that aimed to synthesize High Renaissance ideals, studied Correggio closely, particularly admiring his grace and naturalism. Even El Greco's elongated, ecstatic figures share a certain spiritual intensity found in Correggio.

Proto-Rococo: The sweetness, charm, and delicate sensuality of Correggio's style, especially in his mythological works, anticipated the aesthetics of the 18th-century Rococo period. Artists like François Boucher and Jean-Honoré Fragonard explored similar themes of love and mythology with a comparable lightness and decorative elegance.

Later Appreciation: Although somewhat overshadowed during Mannerism, Correggio's reputation soared from the 17th century onwards. He was highly esteemed by Baroque artists and collectors. In the 19th century, Romantic writers like Stendhal praised the poetic and emotional qualities of his work, contributing to his enduring fame.

Unfinished Works and Interpretations

Like many artists, Correggio left behind works whose status remains debated. The An Allegory of Virtue (now in the Louvre, Paris), along with its companion piece An Allegory of Vice, is sometimes considered unfinished or subject to questions about its exact dating within his career, possibly belonging to his earlier period around 1514-1517 or slightly later.

Additionally, surviving drawings and sketches sometimes show revisions or damage, offering glimpses into his working process but also presenting challenges for interpretation. Some preparatory sketches for larger projects exist, revealing his method of developing complex compositions.

In modern times, the pronounced sensuality and sometimes ambiguous rendering of gender in Correggio's mythological and even religious works have attracted attention, particularly within discussions of queer art history. While there is no historical evidence regarding Correggio's personal life in this regard, the undeniable eroticism and emotional fluidity of his figures continue to provoke discussion and interpretation, highlighting the rich, multi-layered nature of his art.

Conclusion

Antonio Allegri da Correggio remains a pivotal figure in Italian art history. He was a master synthesizer, absorbing lessons from Leonardo, Mantegna, and others, yet forging a style entirely his own. His unparalleled handling of light and shadow created atmosphere and emotional depth, while his daring experiments with perspective revolutionized ceiling painting. His ability to convey both tender human feeling and ecstatic spiritual transport, often imbued with a characteristic sweetness and sensuous grace, marks him as unique. Though working primarily in Parma, his innovations resonated across Europe, profoundly influencing the development of Baroque and Rococo art and securing his place as one of the great masters of the Renaissance. His legacy lies in the beauty, emotion, and technical brilliance that continue to captivate viewers centuries later.