Pietro Berrettini, universally known by the name of his Tuscan hometown as Pietro da Cortona, stands as one of the towering figures of the Italian Baroque. Born in Cortona on November 1, 1596, and dying in Rome on May 16, 1669, his long and prolific career fundamentally shaped the visual language of his era. Primarily celebrated as a painter of breathtaking fresco cycles, Cortona was also a highly original and influential architect and decorator. Alongside his contemporaries Gian Lorenzo Bernini and Francesco Borromini, he defined the exuberant, dynamic, and theatrical style that characterized High Baroque art in Rome, the vibrant center of the Catholic world.

Cortona's impact extended far beyond the execution of individual masterpieces; he synthesized existing artistic currents and forged a powerful new aesthetic that emphasized movement, color, illusionism, and emotional intensity. His work, particularly his monumental ceiling frescoes, became a benchmark for grand-scale decoration throughout Europe for generations to come. Understanding Cortona is essential to grasping the spirit and ambition of 17th-century Italian art.

Early Life and Artistic Formation

Pietro Berrettini was born into a family of artisans in Cortona, Tuscany. His father, Giovanni Berrettini, was a stonemason, providing Pietro with an early, albeit indirect, exposure to the building arts. His initial artistic training, however, was in painting. Around 1609, he entered the workshop of the Florentine painter Andrea Commodi. When Commodi was summoned to Rome around 1612 or 1613, the young Pietro followed his master to the papal city, which would become the main stage for his artistic triumphs.

In Rome, Cortona's training continued under Baccio Ciarpi, a painter of modest talent but one well-connected within the Roman art scene. Perhaps more important than formal instruction was Cortona's immersion in the artistic riches of Rome itself. He diligently studied the masterpieces of antiquity, particularly Roman sculpture, absorbing its forms and narrative power. He also deeply admired the giants of the High Renaissance, including Raphael and Michelangelo, whose works provided models of compositional harmony and figural grandeur.

Furthermore, Cortona absorbed the lessons of more recent predecessors. The vibrant color and dynamic compositions of Venetian masters like Titian and Veronese left a lasting impression. He also studied the revolutionary work of Annibale Carracci, whose frescoes in the Farnese Gallery offered a powerful example of integrating painted narratives within complex architectural frameworks, blending mythological subjects with a sense of naturalism and classical learning. These diverse influences coalesced in Cortona's developing style.

The Sacchetti Patronage: A Springboard to Success

Cortona's career gained significant momentum through the patronage of the Sacchetti family, prominent Florentines residing in Rome. Marcello Sacchetti, treasurer to Pope Urban VIII, and his brother Cardinal Giulio Sacchetti became early and enthusiastic supporters. Around 1620, they commissioned Cortona to paint frescoes depicting scenes from the life of Solomon in their villa at Castel Fusano, near Ostia. Although these early works are now lost, they evidently impressed his patrons.

More significantly, the Sacchetti commissioned several large-scale mythological canvases from Cortona during the 1620s. Among the most important was the Triumph of Bacchus (c. 1624), now in Rome's Capitoline Museums. This work already reveals key elements of Cortona's emerging style: a dynamic, swirling composition filled with numerous figures, rich, warm coloring reminiscent of Titian, and a palpable sense of joyous energy. It demonstrated his ability to handle complex narratives on a grand scale.

During this period, Cortona also undertook commissions to copy works by Raphael and Titian for the Sacchetti, further honing his skills and deepening his understanding of the masters. His association with the Sacchetti family was crucial not only for the commissions themselves but also because it brought him into the orbit of the most powerful patrons in Rome, including the Barberini family, to which Pope Urban VIII belonged. This connection would prove decisive for his career.

The Barberini Ceiling: A High Baroque Masterpiece

The election of Cardinal Maffeo Barberini as Pope Urban VIII in 1623 inaugurated a period of lavish artistic patronage in Rome. The Barberini family sought to express their power and prestige through art and architecture, transforming Rome into a showcase of Baroque splendor. Pietro da Cortona became one of the primary artists entrusted with realizing this vision. His most famous commission, and arguably the defining statement of High Baroque ceiling painting, was the decoration of the Gran Salone of the Palazzo Barberini, the family's magnificent urban palace.

Working primarily between 1633 and 1639, Cortona covered the vast vault with an epic fresco known as the Allegory of Divine Providence and Barberini Power. This complex allegorical work celebrates the glories of the Barberini family and the pontificate of Urban VIII. At the center, Divine Providence, depicted as a majestic female figure, commands Immortality to bestow eternal life, symbolized by a crown of stars, upon the Barberini family emblem (three bees within a laurel wreath).

The fresco is a triumph of illusionism and dynamic composition. Cortona employed a technique known as quadratura, creating painted architectural frameworks that seem to extend the real architecture of the hall into the heavens. Within this framework, scores of figures – allegorical personifications, mythological beings, putti – swirl and soar with incredible energy. The boundaries between the painted architecture and the open sky are blurred, creating a breathtaking sense of depth and movement. This technique, often involving foreshortening known as di sotto in sù (seen from below), draws the viewer into the celestial drama unfolding above.

The Barberini ceiling broke decisively with the more contained, compartmentalized ceiling decorations of the Renaissance and early Baroque, such as Annibale Carracci's Farnese Gallery ceiling, which largely employed quadri riportati (simulated framed easel paintings). Cortona unified the entire vault into a single, overwhelming visual field, a vortex of color, light, and motion. The work's sheer scale, complexity, iconographic richness, and painterly bravura established a new standard for monumental decoration and cemented Cortona's reputation as a leading master. It became a model studied and emulated by artists across Europe.

Cortona as Architect: Innovation in Stone

While primarily known as a painter, Pietro da Cortona was also a highly accomplished and innovative architect. His architectural designs possess the same dynamism, plasticity, and theatricality found in his paintings. He often treated building facades as sculptural entities, using curves, projections, and rich ornamentation to create dramatic effects of light and shadow.

His first major independent architectural commission was the church of Santi Luca e Martina, located near the Roman Forum (rebuilt 1634-1664). As the church of the Accademia di San Luca (the artists' academy of Rome, of which Cortona himself served as Principe or head from 1634-38), it was a particularly prestigious project. Cortona designed both the interior, based on a Greek cross plan, and the exterior. The façade is particularly noteworthy for its elegant convex curve, which seems to gently swell outwards, engaging the surrounding space. This use of curved forms, contrasting with recessed elements, creates a sense of movement and organic unity.

Perhaps Cortona's most celebrated architectural work is the façade and piazza arrangement for Santa Maria della Pace (1656-1657). Here, he demolished some existing structures to create a small, intimate piazza in front of the church. He then designed a striking façade featuring a convex, semi-circular portico supported by paired Tuscan columns. This projecting portico contrasts dramatically with the concave wings flanking it, creating a powerful interplay of forms. The entire composition functions like a stage set, transforming the urban space and drawing the viewer towards the church entrance. It exemplifies the Baroque integration of architecture, urban planning, and theatrical effect.

Cortona also designed the façade of Santa Maria in Via Lata (begun 1658), notable for its sophisticated two-story loggia structure. Earlier, he had designed the Villa Pigneto for the Sacchetti family (c. 1625-1630), an influential suburban villa design known primarily through engravings, as the building itself is now largely ruined. Its complex plan and integration with gardens showcased Cortona's inventive approach to villa architecture. These projects demonstrate Cortona's significant contribution to Baroque architecture, characterized by spatial ingenuity and sculptural dynamism.

Florentine Interlude: The Pitti Palace Frescoes

Cortona's fame extended beyond Rome. In 1637, and then more substantially between 1640 and 1647, he worked in Florence for the Grand Duke Ferdinando II de' Medici. His major commission there was the decoration of a suite of state rooms in the Palazzo Pitti, the Medici's grand ducal residence. These rooms, known as the Planetary Rooms, represent another high point in Cortona's fresco painting.

He decorated the ceilings of the Sala di Venere (Venus), Sala di Giove (Jupiter), Sala di Marte (Mars), and Sala di Apollo. The overall theme was an allegory of Medici virtue and princely education, guided by the virtues associated with each planet and deity. For example, the Sala di Venere depicts the young Medici prince being guided away from the temptations of Venus towards the wisdom of Minerva. The Sala di Giove shows Jupiter crowning the victorious prince, symbolizing just rule.

In these frescoes, Cortona continued to develop the dynamic, illusionistic style of the Barberini ceiling, but adapted it to the different scale and context of the Pitti Palace. He masterfully integrated the painted scenes with elaborate stucco work, executed by his assistants based on his designs. The result is a dazzling ensemble of painting and sculpture, creating an opulent and immersive environment. The rich colors, swirling compositions, and idealized figures contribute to the overall effect of princely magnificence. Cortona left Florence before completing the final room, the Sala di Saturno, which was finished by his most faithful pupil, Ciro Ferri, according to Cortona's designs.

Later Roman Works and Religious Paintings

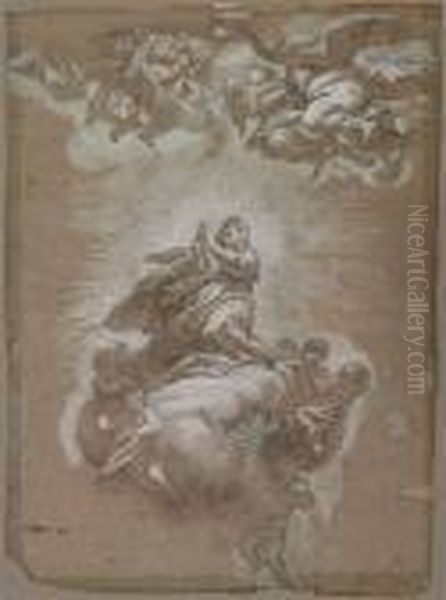

Upon his return to Rome, Cortona remained highly active, undertaking numerous commissions for churches and palaces. One of his most significant later projects was the decoration of the Chiesa Nuova (Santa Maria in Vallicella), the mother church of the Oratorian order. Between 1647 and 1665 (with interruptions), he painted frescoes in the apse (Trinity in Glory), the dome (Assumption of the Virgin), and the nave vault (Miracle of the Madonna della Vallicella). These works demonstrate his continued mastery of large-scale fresco, filled with light, color, and celestial figures in dynamic movement.

Throughout his career, Cortona also produced numerous altarpieces and easel paintings on religious and mythological themes. Notable examples include the Martyrdom of St. Lawrence for San Lorenzo fuori le Mura, Ananias Restoring St. Paul's Sight for Santa Maria della Concezione dei Cappuccini, and The Finding of Romulus and Remus (c. 1643). These works showcase his skill in dramatic narrative, powerful figure drawing, and rich color palettes, often influenced by Venetian painting and the Bolognese school of artists like Guido Reni and Domenichino, though always infused with his characteristic energy.

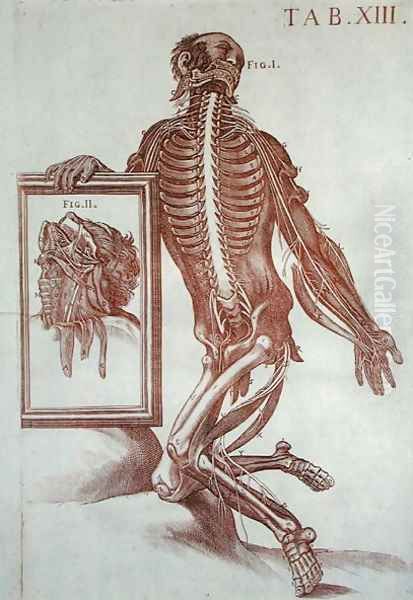

Another fascinating aspect of his output is the series of anatomical drawings he produced around 1618, likely in collaboration with physicians or surgeons. These detailed studies, known as the Tabulae anatomicae, were remarkable for their artistic quality and scientific observation. Although not published until 1741, long after his death, they stand as a testament to the intersection of art and science during the period and Cortona's keen powers of observation.

Artistic Style, Technique, and Debates

Pietro da Cortona's style is the epitome of the High Baroque. It is characterized by:

Dynamism and Movement: His compositions are rarely static. Figures swirl, draperies billow, and architectural elements curve and project, creating a sense of constant energy and flux.

Rich Color and Light: Influenced by Venetian painters like Titian, Cortona employed a warm, vibrant color palette. He used dramatic contrasts of light and shadow (chiaroscuro) to model forms and enhance the emotional impact of his scenes.

Illusionism: Particularly in his ceiling frescoes, Cortona excelled at creating convincing illusions of depth and space, blurring the lines between the real and the painted world using techniques like quadratura and di sotto in sù.

Abundance (Copia): Cortona typically filled his compositions with numerous figures, elaborate details, and complex narratives, creating a sense of richness and grandeur.

Emotional Intensity: His figures often display heightened emotions, contributing to the dramatic power of his religious and mythological scenes.

Cortona's preference for complex, multi-figured compositions placed him at the center of a significant artistic debate in Rome during the 1630s. At meetings of the Accademia di San Luca, a dispute arose between Cortona and the painter Andrea Sacchi, a proponent of a more restrained, classical style influenced by Raphael and Bolognese classicists like Domenichino. Sacchi argued that paintings, like tragedies, should have few figures and a clear, focused narrative to maintain dignity and clarity. Cortona, conversely, argued that large-scale paintings, like epic poems, could and should accommodate many figures and episodes to achieve grandeur and visual richness. This debate highlighted the two main currents within Roman Baroque painting: Cortona's dynamic, decorative High Baroque and Sacchi's more sober classicism, which looked towards artists like Nicolas Poussin.

While Cortona, Bernini, and Borromini are often grouped as the leading triumvirate of the Roman Baroque, their relationships were complex. Cortona collaborated with Bernini on early projects like the Santa Bibiana renovation, and their careers often ran in parallel, sometimes competing for the same patrons. Borromini represented a more idiosyncratic architectural path, though both he and Cortona explored dynamic spatial concepts. Cortona's primary rivals in painting included Sacchi, the classicizing Poussin (a French artist working in Rome), and earlier masters of illusionistic ceiling painting like Giovanni Lanfranco, whose dome fresco in Sant'Andrea della Valle predated Cortona's Barberini ceiling. Other prominent artists active in Rome during Cortona's time included the sculptor Alessandro Algardi and the landscape painter Claude Lorrain.

Workshop, Influence, and Legacy

Like most successful artists of his time, Pietro da Cortona maintained a large and active workshop to help him execute his numerous large-scale commissions. His most important pupil and collaborator was Ciro Ferri (1634-1689), who absorbed Cortona's style so thoroughly that their works can sometimes be difficult to distinguish. Ferri completed several projects left unfinished by Cortona, including the Pitti Palace frescoes and decorations in Santa Maria in Vallicella.

Another significant follower was Giovanni Francesco Romanelli (1610-1662), who also assisted Cortona and later developed his own successful career, working in Rome and Paris. Other pupils included Giacinto Gimignani and Lazzaro Baldi. Through his students and the widespread admiration for his major works, Cortona's style exerted a profound influence on the subsequent development of Baroque painting, not only in Rome but also in Florence, Naples (influencing artists like Luca Giordano), Genoa, and beyond.

His approach to monumental ceiling decoration, blending illusionistic architecture with dynamic figural compositions, became a dominant model for palace and church decoration throughout Europe in the late 17th and 18th centuries. Aspects of his energetic style and decorative sensibility can be seen feeding into the Rococo period, particularly in the grand ceiling frescoes of artists like Giovanni Battista Tiepolo in Venice and Würzburg.

In his later years, Cortona dedicated more time to architecture and also collaborated with the Jesuit theologian G. Domenico Ottonelli on a treatise, Trattato della pittura e scultura, uso et abuso loro (Treatise on Painting and Sculpture, their Use and Abuse), published in 1652. This work defended the role of religious art against potential criticisms, reflecting the Counter-Reformation climate. Pietro da Cortona died in Rome in 1669, recognized as one of the defining artists of his age.

Conclusion: A Defining Force of the Baroque

Pietro da Cortona's contribution to the arts of 17th-century Italy was immense and multifaceted. As a painter, he revolutionized monumental fresco decoration, creating immersive, dynamic, and emotionally charged environments that perfectly expressed the grandeur and religious fervor of the Baroque era. His Barberini ceiling remains one of the undisputed masterpieces of European painting. As an architect, he brought a painter's eye for plasticity and theatricality to his building designs, creating innovative facades and spatial arrangements that engaged the viewer and shaped the urban landscape of Rome.

Working alongside Bernini and Borromini, Cortona helped forge the visual language of the High Baroque, a style characterized by energy, illusion, and ornate splendor. His ability to synthesize influences from the Renaissance, Venetian colorists, and contemporary innovators, combined with his own innate talent for dynamic composition and grand narrative, resulted in a powerful and enduring artistic legacy. From the soaring vaults of Roman palaces and churches to the elegant curves of his architectural facades, the work of Pietro da Cortona continues to impress viewers with its technical brilliance, imaginative power, and sheer exuberant vitality, embodying the very spirit of the Baroque age.