Introduction: A Classical Voice in Baroque Rome

Andrea Sacchi (1599/1600–1661) stands as a pivotal figure in the landscape of seventeenth-century Italian art. Active primarily in Rome, he emerged as a leading proponent of the classical strand within the exuberant Baroque era. While contemporaries like Gian Lorenzo Bernini and Pietro da Cortona pushed the boundaries of dynamic movement and dramatic intensity, Sacchi championed a more restrained, ordered, and intellectually grounded approach to painting. Deeply influenced by the High Renaissance master Raphael, Sacchi forged a style characterized by clarity, compositional harmony, and psychological depth. He was not only a highly respected painter, sought after by prominent patrons including the powerful Barberini family, but also an influential theorist whose ideas sparked significant debate within the Roman artistic community. His legacy, carried forward by his pupils, most notably Carlo Maratti, ensured the continuation of the classical tradition well into the later Baroque period.

Early Life and Artistic Formation

Born in Nettuno, a coastal town near Rome, around 1599 or 1600, Andrea Sacchi's initial artistic exposure came through his father, Benedetto Sacchi. However, Benedetto was reportedly a painter of modest abilities, and the young Andrea's formal training took place elsewhere. Crucially, he entered the workshop of Francesco Albani, a prominent painter who had himself trained under the Carracci in Bologna before establishing a successful career in Rome. Albani was a key figure in transmitting the ideals of Bolognese classicism, which emphasized drawing, idealized forms, and compositional clarity derived from Renaissance models, particularly Raphael.

Working under Albani provided Sacchi with a solid foundation in drawing and composition, and instilled in him an appreciation for the classical tradition. Albani's own work, often featuring mythological or religious scenes set in idyllic landscapes, showcased a lyrical and graceful style that left an imprint on his pupil. During his formative years, Sacchi would have absorbed the artistic currents swirling through Rome, a city brimming with the legacy of Renaissance masters and the burgeoning energy of the early Baroque, including the dramatic naturalism of Caravaggio and his followers. However, it was the lineage of Raphael and the Bolognese classicists that would prove most decisive for Sacchi's artistic trajectory. He became recognized early on as one of the most skilled colourists emerging from Albani's studio.

The Emergence of a High Baroque Classicist

As Sacchi matured as an independent artist, he increasingly aligned himself with the classical trend in Roman art. This movement sought a balance between the dynamism of the Baroque and the order, grace, and idealized beauty associated with Raphael and antiquity. Sacchi found kindred spirits in the sculptor Alessandro Algardi and the Flemish sculptor François Duquesnoy, both active in Rome. Together, these artists formed a significant counterpoint to the more flamboyant High Baroque style epitomized by Bernini and Pietro da Cortona. Sacchi's classicism was not a mere imitation of the past but a reinterpretation of its principles for a new age.

His style became characterized by a deliberate and thoughtful approach. He favoured compositions with a limited number of figures, allowing each to be clearly delineated and psychologically expressive. This contrasted sharply with the teeming, complex narratives often found in the work of Cortona. Sacchi emphasized clarity of design, elegant contours, and a harmonious balance of forms. His use of colour was refined and subtle, contributing to the overall sense of calm, dignity, and restrained emotion that permeates his major works. He drew profound inspiration from Raphael, seeking to emulate the Renaissance master's compositional harmony, idealized figures, and narrative lucidity. This dedication to classical principles positioned him as a leading figure of what art historians term "High Baroque Classicism."

Major Commissions and Masterpieces

Sacchi's talent and his adherence to classical ideals attracted significant patronage from the Church and powerful Roman families. His reputation grew steadily, leading to several major commissions that cemented his status as one of Rome's foremost painters.

The Vision of St. Romuald

Created around 1631 for the church of San Romualdo in Rome (now housed in the Pinacoteca Vaticana), The Vision of St. Romuald is widely regarded as one of Sacchi's defining masterpieces and a cornerstone of Baroque classicism. The painting depicts the founder of the Camaldolese order recounting his vision to fellow monks – a vision where deceased members of the order ascend a ladder to heaven, clad in white robes. Sacchi masterfully conveys the scene's quiet intensity and spiritual gravity.

The composition is remarkably stable and clear. St. Romuald, seated slightly off-center, gestures towards the sky, while five monks, arranged in a semi-circle, listen intently. Their white habits create large, simple masses of form, contributing to the painting's monumental calm. Sacchi avoids dramatic foreshortening or violent movement, instead focusing on the subtle variations in posture and expression to convey the monks' rapt attention and the saint's profound experience. The restrained palette, dominated by whites, greys, and earthy tones, and the soft, unifying light further enhance the atmosphere of serene contemplation. This work perfectly embodies Sacchi's principle of using few figures to achieve maximum expressive impact. It stood in stark contrast to the more agitated altarpieces common in the period and was highly influential.

The Miracle of St. Gregory the Great

Another significant commission was the large altarpiece for the Altar of St. Gregory the Great in St. Peter's Basilica, painted between 1625 and 1630 (the original is now in the Pinacoteca Vaticana, replaced by a mosaic copy in the basilica). The subject depicts a Eucharistic miracle associated with Pope Gregory I: during Mass, a woman doubted the real presence of Christ in the consecrated bread, whereupon the host visibly transformed into flesh and blood. Sacchi presents the event with solemnity and clarity.

St. Gregory stands at the altar, displaying the miraculous host, while figures around him react with awe and reverence. The composition is carefully structured, guiding the viewer's eye towards the central miracle. While demonstrating Sacchi's ability to handle a large-scale, multi-figure composition for a prestigious location, the work maintains a sense of order and decorum consistent with his classical leanings. The choice of this specific miracle, rather than perhaps a more commonly depicted event from the saint's life, might reflect the Counter-Reformation emphasis on the doctrine of Transubstantiation, and Sacchi's interpretation presents it with theological clarity and artistic dignity.

Divine Wisdom at Palazzo Barberini

Perhaps Sacchi's most ambitious undertaking was the ceiling fresco Allegory of Divine Wisdom (1629–1633) in the Palazzo Barberini, the opulent residence of Pope Urban VIII's family. This commission placed Sacchi in direct comparison—and potential rivalry—with Pietro da Cortona, who was simultaneously decorating the vast ceiling of the palace's main salone with his Allegory of Divine Providence and Barberini Power. Sacchi's work occupies a smaller room but is no less significant in demonstrating his artistic principles.

The fresco depicts Divine Wisdom enthroned among allegorical figures representing attributes like Purity, Justice, Strength, and Beauty, all set against a simulated architectural framework that opens to a celestial sky. The composition is centralized and relatively static compared to Cortona's dynamic vortex of figures. Sacchi uses a clear, geometric structure, possibly influenced by his understanding of architecture and perspective, to organize the scene. The figures are statuesque and idealized, recalling Raphael's frescoes in the Vatican Stanze. The colour scheme is luminous and harmonious. While Cortona's ceiling overwhelms with its sheer energy and illusionistic bravura, Sacchi's Divine Wisdom offers a more measured, intellectually conceived allegory, embodying order, stability, and the eternal nature of divine knowledge. It is a quintessential statement of High Baroque Classicism applied to ceiling decoration.

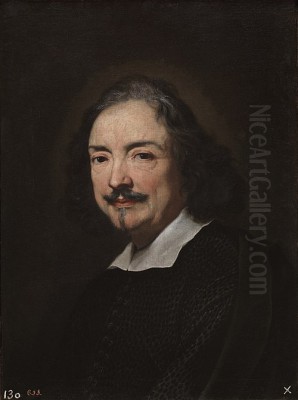

Other Works and Portraiture

Beyond these major public commissions, Sacchi was also a skilled portraitist, capturing the likenesses of patrons and clergymen with sensitivity and dignity, often employing a restrained palette and focusing on the sitter's character. He continued to produce altarpieces and easel paintings on religious and mythological themes throughout his career, consistently applying his principles of clarity, balance, and refined execution. His works were sought after by discerning collectors who appreciated his departure from the more theatrical excesses of the mainstream Baroque. He also undertook decorative projects, such as frescoes for the Barberini's private chapel, further demonstrating his versatility.

The Sacchi-Cortona Debate: Classicism vs. High Baroque

One of the most famous episodes in Sacchi's career, and a key moment in Baroque art theory, was his public debate with Pietro da Cortona at the Accademia di San Luca, Rome's academy of artists. Taking place likely around 1636, the debate centered on the appropriate number of figures in a history painting. Sacchi, representing the classical viewpoint, argued for compositional simplicity and restraint. He contended that paintings, like classical tragedies, should focus on a few essential figures to maintain clarity, unity, and emotional impact. Too many figures, he believed, would distract the viewer and dilute the central narrative, creating confusion rather than grandeur. He advocated for quality over quantity, emphasizing the distinct expression and role of each figure.

Pietro da Cortona, whose own work exemplified the dynamic, multi-figured compositions of the High Baroque, argued the opposing view. He compared history painting to epic poetry, suggesting that a large number of figures and complex subplots could enrich the narrative and enhance the sense of grandeur and spectacle. For Cortona, abundance and complexity were virtues that demonstrated the artist's invention and skill (copia).

This debate was more than just a technical disagreement; it reflected fundamental differences in aesthetic philosophy. Sacchi championed the values of order, clarity, decorum, and intellectual contemplation derived from Renaissance ideals and classical antiquity. Cortona represented the Baroque fascination with movement, drama, emotional intensity, and overwhelming visual effect. While Sacchi's arguments resonated with artists who favoured a more measured approach, like the French painter Nicolas Poussin (who was working in Rome at the time and likely aware of, if not present at, the debates), Cortona's visually spectacular style arguably had a more immediate and widespread impact on the prevailing taste of the era. Nevertheless, the debate solidified Sacchi's position as the leading intellectual voice of Roman classicism and highlighted the stylistic plurality within the Baroque period.

Sacchi as Theorist and Teacher

Although Andrea Sacchi did not leave behind extensive written treatises like some earlier art theorists, his ideas were influential and widely disseminated through his work, his teaching, and his participation in academic discussions like the debate with Cortona. His theoretical stance consistently emphasized the principles of classicism adapted to the seventeenth-century context. He believed in the importance of decorum—the appropriateness of style and representation to the subject matter. Noble themes, drawn from the Bible, mythology, or ancient history, required a grand, idealized style, distinct from the low or vulgar subjects.

Sacchi stressed the importance of clarity (chiarezza) in narrative and composition. He advocated for a rational structure, often employing stable, geometric arrangements and avoiding excessive complexity. His emphasis on psychological expression, achieved through subtle gesture and physiognomy rather than overt theatricality, also aligned with classical ideals. Furthermore, his technical mastery, particularly his refined use of colour and his understanding of light and perspective, underpinned his theoretical positions, demonstrating that classical restraint did not preclude painterly skill or visual appeal.

Sacchi's influence extended significantly through his role as a teacher. His studio attracted talented pupils who were drawn to his classical approach. By far the most important of these was Carlo Maratti (or Maratta). Maratti absorbed Sacchi's principles of composition, idealized figures, and refined technique, becoming the leading painter in Rome in the later seventeenth century. Maratti skillfully blended Sacchi's classicism with a richer colour palette and a slightly softer, more graceful style, effectively creating a synthesis that dominated Roman painting for decades. Through Maratti, Sacchi's classical legacy was transmitted to subsequent generations of artists, ensuring its persistence alongside the more exuberant Baroque trends. Other artists associated with Sacchi's circle or influenced by him further propagated this classical current.

Later Life, Personal Hardships, and Legacy

Andrea Sacchi's later years were marked by personal sorrow and declining health. The premature death of his son, Giuseppe, was a significant blow. Sources also suggest that he suffered from illness in his final years, which may have impacted his artistic production, although he remained a respected figure in the Roman art world. Despite these challenges, he continued to work, maintaining his commitment to the classical principles he had championed throughout his life.

He died in Rome on June 21, 1661, and was buried in the church of San Giovanni in Laterano. At the time of his death, his reputation as a master of the classical style was firmly established. While the more dynamic Baroque of artists like Bernini and Cortona might have captured the popular imagination more forcefully during the mid-seventeenth century, Sacchi's quieter, more intellectual art offered a compelling alternative that appealed to discerning patrons and fellow artists.

His legacy proved enduring. Through his own masterpieces, such as The Vision of St. Romuald and Divine Wisdom, he provided powerful exemplars of High Baroque Classicism. His theoretical arguments, particularly those articulated in the debate with Cortona, framed key aesthetic questions for his generation. Most importantly, through his pupil Carlo Maratti, Sacchi's style and principles were adapted and perpetuated, becoming the dominant force in Roman painting in the late Baroque and influencing the transition towards Neoclassicism in the eighteenth century. Artists like Nicolas Poussin, though developing his own distinct form of classicism, shared intellectual affinities with Sacchi and operated within the same Roman milieu that valued classical ideals. Sacchi's influence can also be seen in the context of the broader Bolognese tradition, connecting back through his teacher Albani to the Carracci, and looking forward to later classicizing trends. He remains a crucial figure for understanding the complex artistic landscape of Baroque Rome, representing the powerful and persistent appeal of classical order, clarity, and idealized beauty amidst the era's characteristic dynamism and drama.

Conclusion: The Enduring Appeal of Order

Andrea Sacchi carved a distinct and influential path through the vibrant and often tumultuous world of Roman Baroque art. As both a painter and a theorist, he stood as a steadfast advocate for the principles of classicism, drawing inspiration from Raphael and antiquity while engaging critically with the artistic innovations of his time. His major works, characterized by compositional clarity, psychological depth, refined colour, and a sense of monumental calm, offered a compelling alternative to the exuberant dynamism favoured by contemporaries like Pietro da Cortona. The famous debate between these two artists crystallized the central aesthetic tensions of the era. Through his influential teaching, particularly of Carlo Maratti, Sacchi ensured that the classical tradition not only survived but flourished, shaping the course of Roman painting for generations. He remains a testament to the enduring power of order, harmony, and intellectual rigor in art, even within the heart of the Baroque.