Nicolas Poussin stands as a towering figure in the history of Western art, the principal founder and greatest practitioner of 17th-century French Classicism. Born in France but spending most of his productive life in Rome, Poussin forged a unique artistic path defined by intellectual rigor, emotional restraint, and a profound engagement with the classical past. His paintings, often depicting scenes from the Bible, mythology, and ancient history, are celebrated for their clarity of composition, narrative force, and philosophical depth. In an era dominated by the dramatic dynamism of the Baroque, Poussin offered a compelling alternative rooted in reason, order, and harmony, leaving an indelible mark on the trajectory of European art.

Early Life and Formation

Nicolas Poussin was born near Les Andelys in Normandy, France, likely on June 15, 1594. While details of his earliest years are scarce, it's clear he displayed an aptitude for drawing early on. Local painter Quentin Varin is credited with giving Poussin some initial instruction around 1612, perhaps inspiring the young artist to pursue his vocation more seriously. Shortly thereafter, against his family's wishes, Poussin left Normandy for Paris, eager to immerse himself in a more vibrant artistic environment.

In Paris, Poussin's education was somewhat fragmented. He spent brief periods in the studios of minor masters, including the Flemish portraitist Ferdinand Elle and possibly Georges Lallemand. More significant, perhaps, was his access to the royal collections and his study of engravings after Italian Renaissance masters, particularly Raphael and Titian. He also likely encountered works by the School of Fontainebleau. During this formative period, he honed his drawing skills and absorbed lessons in perspective and anatomy, possibly through connections with the court mathematician Alexandre Courtois. He also befriended Philippe de Champaigne, another artist who would become a major figure in French painting.

Poussin's ambition from early on was to travel to Rome, the undisputed center of the art world and the living repository of the classical tradition he increasingly admired. An initial attempt to reach Italy ended prematurely in Florence. Financial constraints and perhaps a lack of significant commissions hampered his progress. A crucial connection proved to be the Italian poet Giambattista Marini, who was residing in Paris. Marini recognized Poussin's talent, employed him to create a series of drawings illustrating Ovid's Metamorphoses, and encouraged his move to Rome.

Arrival and Ascent in Rome

Finally, in 1624, at the age of thirty, Poussin arrived in Rome. This move marked the true beginning of his mature career. He arrived during the pontificate of Urban VIII (Maffeo Barberini), a period of extraordinary artistic activity. Rome was dominated by the High Baroque, exemplified by the dramatic sculptures of Gian Lorenzo Bernini and the exuberant ceiling frescoes of Pietro da Cortona. Poussin absorbed the energy of the city but charted his own course.

Initially, he faced hardship. His patron Marini soon departed for Naples (where he died shortly after), leaving Poussin without his primary support. He reportedly struggled, possibly selling paintings for meager sums. However, his talent gradually gained recognition. He studied antique sculpture intensely, frequented the city's churches and collections, and absorbed the lessons of Renaissance masters like Raphael and Titian, as well as contemporary classicizing Bolognese painters such as Domenichino and Guido Reni. While he learned from the dramatic lighting of Caravaggio, he ultimately rejected the raw naturalism and intense emotionalism characteristic of Caravaggism.

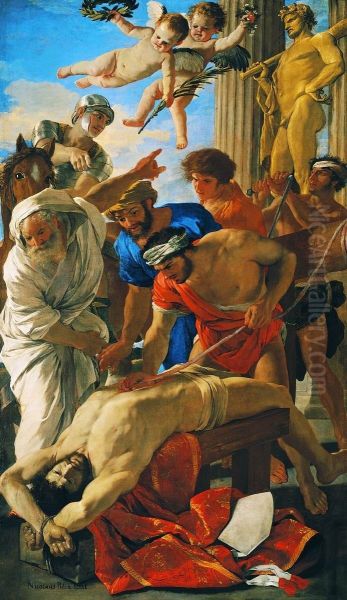

A significant early commission came through the Barberini circle: The Death of Germanicus (1627-1628), painted for Cardinal Francesco Barberini, the Pope's nephew. This work, depicting a stoic scene from Roman history with clarity and gravitas, established Poussin's reputation as a serious history painter. Another major, though less personally satisfying, commission was The Martyrdom of St. Erasmus (1628-1629) for St. Peter's Basilica. While demonstrating his ability to work on a grand scale, the painting's somewhat overt drama hinted at Baroque tendencies he would later temper.

During these years, Poussin found a crucial intellectual and social circle around Cassiano dal Pozzo, a scholar, antiquarian, and secretary to Cardinal Barberini. Dal Pozzo became a loyal patron and friend, sharing Poussin's deep interest in classical antiquity. His vast collection of drawings documenting Roman artifacts, known as the "Paper Museum," was an invaluable resource for the artist. Through dal Pozzo, Poussin deepened his understanding of ancient history, mythology, and philosophy, which became central to his art.

The Development of Poussin's Classicism

By the late 1620s and early 1630s, Poussin had fully developed his distinctive classical style. This style prioritized disegno (design, drawing, and the intellectual conception of the work) over colore (color and painterly handling, often associated with Venetian art). His compositions became meticulously planned, often based on geometric principles, creating a sense of stability and order. Figures were arranged clearly across the picture plane, often resembling classical relief sculpture.

His goal was not simply to imitate antiquity but to emulate its underlying principles: rationality, clarity, harmony, and moral seriousness. He believed painting should appeal to the mind as much as to the eye, conveying significant narratives with decorum and intellectual weight. Emotion was present but controlled, expressed through gesture and pose (what he termed the "modes" or affections) rather than through overt melodrama. His subjects were drawn primarily from the Bible, Ovid's Metamorphoses, and Roman history, chosen for their potential to convey universal human themes and moral lessons.

Key works from this period exemplify his mature classicism. The Plague at Ashdod (1630-1631) depicts a biblical catastrophe with harrowing detail but within a rigorously structured composition. The Rape of the Sabine Women (two versions, c. 1634-1635 and c. 1637-1638) transforms a chaotic historical event into a complex, frozen ballet of conflicting movements. Perhaps his most famous work from this era is Et in Arcadia Ego (also known as The Arcadian Shepherds, c. 1637-1638, Louvre version), a meditative scene where shepherds contemplate a tomb inscription, evoking themes of mortality, memory, and the passage of time within an idealized pastoral landscape. This painting, with its balanced composition and elegiac mood, became an emblem of the classical ideal.

Poussin developed a meticulous working method. He created numerous preparatory drawings, working out the composition and individual figures. Famously, he also constructed small wax figures that he arranged on a miniature stage, allowing him to study the effects of light and the relationships between figures in three dimensions before committing the scene to canvas. This deliberate, almost scientific approach underscores the intellectual foundation of his art.

Poussin and His Contemporaries

Poussin's classicism set him apart from many contemporaries in Rome. While he respected artists like Domenichino and Andrea Sacchi, who shared a more classical orientation, he stood in contrast to the dominant High Baroque style of Pietro da Cortona and Bernini, whose works emphasized dynamism, illusionism, and overwhelming emotional impact. Poussin’s measured, intellectual approach offered a distinct alternative.

His relationship with fellow French painter Simon Vouet, who had arrived in Rome shortly before him and achieved considerable success, was complex. Initially, they moved in similar circles, but as Poussin's reputation grew, rivalry emerged. Vouet, who returned to Paris in 1627 to become the leading painter at the French court, represented a more decorative, Italianate Baroque style that differed significantly from Poussin's developing classicism. This rivalry would resurface during Poussin's later, brief return to Paris.

Poussin maintained a friendship with Claude Lorrain, another French painter who settled permanently in Rome. Both artists revolutionized landscape painting, elevating it from mere background to a primary subject imbued with poetic feeling. However, their approaches differed: Claude specialized in idealized, atmospheric landscapes bathed in golden light, often with mythological or biblical figures playing a secondary role. Poussin's landscapes, while equally idealized, were more structured, often serving as carefully constructed settings for significant human actions, reflecting his belief in nature's underlying order.

Poussin generally avoided direct comparison or competition with the Flemish master Peter Paul Rubens, the titan of Northern Baroque painting. Rubens's exuberant color, dynamic compositions, and sensual energy were antithetical to Poussin's restrained classicism. While both drew inspiration from Titian and antiquity, their interpretations diverged dramatically, representing two poles of 17th-century art. Poussin's emphasis on line and form contrasted sharply with Rubens's painterly bravura.

Poussin also attracted followers and assistants, most notably his brother-in-law Gaspard Dughet, who became a successful landscape painter in his own right, specializing in scenes of the Roman Campagna, often reflecting a Poussin-esque structure but with a more romantic sensibility. Charles Le Brun, who would later dominate French art under Louis XIV, spent time with Poussin in Rome and absorbed key elements of his classical doctrine.

The Parisian Interlude

By the late 1630s, Poussin's fame had reached the highest levels in France. King Louis XIII and his powerful chief minister, Cardinal Richelieu, were determined to lure the celebrated artist back to Paris to work on prestigious royal projects, particularly the decoration of the Grande Galerie of the Louvre Palace. Despite his deep attachment to Rome and reluctance to leave his established life and intellectual circle, Poussin felt compelled to obey the royal summons.

He arrived in Paris in December 1640 and was received with great honor, appointed First Painter to the King. However, the Parisian sojourn (1640-1642) proved deeply unhappy for him. He disliked the pressures of the court, the demands for large-scale decorative works (including altarpieces and designs for tapestries), and the intrigues of rival artists, particularly the circle around his old competitor, Simon Vouet. He felt his artistic integrity was compromised by projects that did not suit his temperament or his meticulous working methods.

His work on the Grande Galerie decorations did not proceed smoothly, and he complained bitterly about the conditions and the lack of understanding for his art. Although he produced some significant works during this period, including the altarpiece The Institution of the Eucharist for the royal chapel at Saint-Germain-en-Laye, his letters reveal profound dissatisfaction. Using the pretext of needing to fetch his wife, Anne-Marie Dughet (whom he had married in Rome in 1630), Poussin obtained leave to return to Rome in September 1642. He never went back to France. The deaths of Richelieu later that year and Louis XIII in 1643 removed the main sources of pressure for his return.

Late Works and Philosophical Depth

Back in the familiar and supportive environment of Rome, Poussin entered the final, highly productive phase of his career. Freed from the demands of the French court, he concentrated on easel paintings for a select group of discerning patrons, including Cassiano dal Pozzo and French collectors like Paul Fréart de Chantelou. His late works are characterized by an increasing austerity, profound philosophical depth, and a masterful integration of figures and landscape.

During the 1640s, he painted the second series of The Seven Sacraments for Chantelou (1644-1648), considered by many to be among his greatest achievements. Compared to the first series (painted for dal Pozzo in the late 1630s), these later versions are more severe, compositionally rigorous, and emotionally restrained, embodying a stoic gravity. Works like The Holy Family on the Steps (1648) showcase his mastery of stable, geometric composition and serene, contemplative mood.

Landscape gained increasing prominence in his late works, evolving from a backdrop into a primary carrier of meaning. Paintings like Landscape with Diogenes (c. 1647) and Landscape with Polyphemus (1649) depict nature as a powerful, ordered force, a grand stage for philosophical reflection or mythological enactment. These landscapes are not direct transcriptions of reality but carefully composed idealizations, reflecting Stoic ideas about harmony between humanity and the natural world.

His final masterpieces were the four canvases depicting The Four Seasons (1660-1664), painted for the Duc de Richelieu (nephew of the Cardinal). Each season is represented by a biblical scene set within a specific landscape, evoking the cyclical nature of life, death, and redemption: Spring (Adam and Eve in the Garden of Eden), Summer (Ruth and Boaz), Autumn (The Spies with the Grapes of the Promised Land), and Winter (The Deluge). These works are imbued with a powerful sense of cosmic drama and profound melancholy, particularly the stark and terrifying Winter.

In his later years, Poussin suffered from a tremor in his hands, which gradually made painting more difficult. His last, unfinished painting was Apollo and Daphne (1664). He painted two remarkable self-portraits (1649 and 1650), presenting himself as a stern, intellectual figure, a painter-philosopher dedicated to the highest ideals of his art. Nicolas Poussin died in Rome on November 19, 1665, and was buried in the church of San Lorenzo in Lucina, his parish church for over forty years.

Artistic Methods and Theories

Poussin was one of the most intellectual painters of his time, deeply read in classical literature, history, and philosophy, particularly Stoicism. He believed that painting, like poetry, should instruct and elevate the viewer. His art was grounded in theory, most famously his concept of the "modes." Borrowing from ancient Greek musical theory, Poussin argued that a painting's style should be adapted to its subject matter. A grave subject required a severe mode, while a joyous subject demanded a lighter one. This involved careful choices regarding composition, drawing, color, and the expression of figures' emotions ("affections").

His meticulous preparation, involving extensive reading, numerous drawings, and the use of his model stage or "boîte optique," ensured that every element of the final painting contributed to its overall meaning and effect. He sought clarity above all, aiming to make the narrative legible and the underlying message clear to the attentive viewer. While admired for his compositional harmony and intellectual depth, his deliberate approach and emotional restraint sometimes led critics, particularly those favoring Baroque exuberance, to find his work cold or overly academic.

Legacy and Influence

Nicolas Poussin's influence on the course of art, particularly in France, was immense and enduring. Although he spent most of his life in Rome, he became the cornerstone of the French academic tradition. His principles of clarity, order, and intellectual seriousness were codified by Charles Le Brun and dominated the teachings of the French Royal Academy of Painting and Sculpture for generations. The famous debates within the Academy between the "Poussinistes" (who championed line and design) and the "Rubénistes" (who favored color and painterly freedom) demonstrated his central position in French art theory.

He was a crucial model for the Neoclassical painters of the late 18th century, most notably Jacques-Louis David, whose Oath of the Horatii clearly echoes Poussin's compositional rigor and moral gravity. Artists like Jean-Auguste-Dominique Ingres also looked to Poussin as a master of line and classical form. Even much later, modern artists found inspiration in his work; Paul Cézanne famously declared his desire to "redo Poussin after nature," seeking to combine the structural logic of the old master with the immediacy of Impressionist observation. Poussin remains the archetypal "painter-philosopher," an artist whose work continues to reward close looking and intellectual engagement.

Major Collections

Nicolas Poussin's works are held in major museums around the world, reflecting his international stature. The most significant collection resides in the Musée du Louvre in Paris, which holds masterpieces such as Et in Arcadia Ego, The Four Seasons, The Rape of the Sabine Women, The Plague at Ashdod, and one of his self-portraits.

The National Gallery in London also possesses a strong collection, including The Adoration of the Golden Calf, Landscape with a Man Killed by a Snake, and The Triumph of Pan. The Museo del Prado in Madrid houses important works like The Triumph of David and Parnassus.

In the United States, major paintings can be found at the National Gallery of Art in Washington, D.C. (The Assumption of the Virgin, The Holy Family on the Steps from the Kress Collection), the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York (The Abduction of the Sabine Women), the Getty Center in Los Angeles, and the Kimbell Art Museum in Fort Worth (housing much of the first Seven Sacraments series). Other notable holdings are in the Gemäldegalerie in Berlin (Realm of Flora), the National Gallery of Ireland (Lamentation over the Dead Christ), the Ashmolean Museum in Oxford, and the Fitzwilliam Museum in Cambridge (Extreme Unction from the second Sacraments series). The Musée Condé in Chantilly holds The Massacre of the Innocents.

Conclusion

Nicolas Poussin carved a unique and enduring path through the complex artistic landscape of the 17th century. By synthesizing his deep study of classical antiquity and Renaissance masters with his own intellectual rigor and artistic vision, he created a form of classicism that was both timeless and profoundly personal. His paintings, characterized by their clarity, order, and philosophical depth, offered a powerful counterpoint to the prevailing Baroque aesthetic. As the foundational figure of French Classicism and an inspiration to generations of artists from David to Cézanne, Poussin's legacy remains central to the understanding of European art history. His work continues to speak to viewers through its harmonious compositions, compelling narratives, and the enduring power of reason and reflection in art.