Earl Horter stands as a significant, if sometimes overlooked, figure in the narrative of early 20th-century American art. A largely self-taught artist, he excelled as a printmaker, particularly in etching, and as a watercolorist, capturing the burgeoning urban landscapes of his time. Beyond his own artistic contributions, Horter was an avid and insightful collector of modern art, amassing an important collection that included works by European avant-garde masters. His life and career offer a fascinating glimpse into the artistic ferment of cities like Philadelphia and New York, and his passion for modernism played a crucial role in its dissemination and appreciation in America.

Early Life and Artistic Awakenings

Born in 1881 in Germantown, Pennsylvania, a historic neighborhood of Philadelphia, Earl Horter's upbringing was in a working-class environment. This background perhaps instilled in him a practical resourcefulness that would define his early artistic endeavors. Unlike many of his contemporaries who benefited from formal academic training in Europe or established American art academies, Horter's initial foray into the art world was through commercial application. As a teenager, he began his career by engraving stock certificates for the prominent John Wanamaker department store, a meticulous craft that undoubtedly honed his precision and control of line.

This early experience with engraving laid a foundational skill set for his later work in etching. While largely self-taught, Horter did seek some formal instruction. He studied etching under James Fincken at the Philadelphia Sketch Club, one of the oldest artists' clubs in America. This period was crucial for Horter, allowing him to refine his technique and connect with a community of artists, which was vital for an aspiring talent in the pre-modernist era of Philadelphia's art scene.

New York and the Development of a Professional Artist

In 1903, seeking broader opportunities and a more dynamic artistic environment, Horter moved to New York City. The city was rapidly transforming into a global metropolis, its towering skyscrapers and bustling energy providing rich subject matter for artists. Horter immersed himself in this milieu, initially working as a commercial illustrator for advertising agencies, including a notable stint at Calkins and Holden. His skill and professionalism soon led him to a significant role as an art director for N.W. Ayer & Son, one of the leading advertising firms, where he worked for six years. This commercial work, while demanding, provided him with financial stability and kept him engaged with visual communication, albeit in a commercial context.

Despite the demands of his commercial career, Horter continued to develop his personal artistic practice. His etchings and watercolors from this period began to gain recognition. He was particularly drawn to the urban environment, capturing the architectural forms, atmospheric conditions, and industrial character of New York and, later, Philadelphia. His approach was rooted in realism, but an evolving sensibility towards modern compositional strategies began to emerge.

A significant milestone in his career as a fine artist came in 1916 with his first solo exhibition at the prestigious Frederick Keppel & Company gallery in New York. This gallery was renowned for its specialization in prints. The exhibition was curated by Carl Zigrosser, a highly influential figure in the print world who would later become the first curator of prints and drawings at the Philadelphia Museum of Art and subsequently at the Museum of Modern Art, New York. Zigrosser's early championing of Horter's work underscores the quality and originality of his prints.

The Printmaker's Eye: Capturing the Urban Landscape

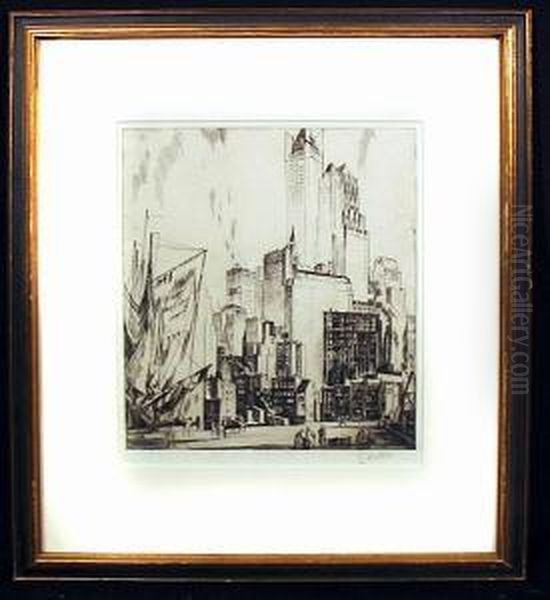

Earl Horter's reputation as an artist is significantly built upon his mastery of etching. He possessed a remarkable ability to translate the gritty reality and emerging monumentality of the American city onto the copper plate. His urban scenes were not merely topographical records; they were imbued with a sense of atmosphere and a keen eye for compositional drama. He explored the play of light and shadow on stone and steel, the intricate patterns of industrial structures, and the often-overlooked corners of the urban fabric.

His etchings often depicted iconic New York landmarks, industrial sites, and street scenes. Works like "Dark House," an etching now in the collection of the Detroit Institute of Arts, exemplify his skill in creating mood and texture through intricate line work and tonal variation. Another notable piece, "Church in the Snow" (circa 1920-1930), an etching with watercolor, showcases his ability to combine the precision of etching with the expressive potential of color, capturing a quiet, atmospheric moment within the city.

Horter's style, while fundamentally realist, began to show the subtle influences of modernism. His compositions often employed strong diagonals, cropped views, and an emphasis on geometric forms, hinting at an awareness of movements like Cubism and Precisionism, even if his work did not fully embrace their abstract tendencies. Artists like John Sloan and Joseph Pennell were also active printmakers of urban scenes, though Pennell's style was more traditionally picturesque, while Sloan, part of the Ashcan School, focused more on the human element within the city. Horter carved his own niche, focusing on the architectural and industrial character of the modernizing American city.

Embracing Modernism: The Collector's Passion

Parallel to his own artistic development, Earl Horter cultivated an extraordinary passion for modern art. This was perhaps the most defining aspect of his contribution to American art history. Beginning around 1909, and with increasing intensity through the 1910s and 1920s, Horter began to acquire works by the leading figures of the European avant-garde. His collection became one of the most important private holdings of modern art in America at the time, particularly remarkable given that he was not a man of immense wealth but rather used his earnings as a commercial artist and illustrator to fund his acquisitions.

His collection was particularly strong in Cubist works. He owned seminal pieces by Pablo Picasso and Georges Braque, the co-founders of Cubism. His holdings included paintings and works on paper that traced the development of Analytical and Synthetic Cubism. He also acquired significant works by Juan Gris, another key figure in the Cubist movement, and Fernand Léger, whose distinctive "Tubist" style was a variation of Cubism.

Beyond Cubism, Horter's collection demonstrated a broad and sophisticated understanding of modern art. He owned works by Marcel Duchamp, including studies related to Duchamp's groundbreaking "Nude Descending a Staircase, No. 2," which had caused a sensation at the Armory Show. The collection also featured pieces by Constantin Brâncuși, the Romanian sculptor whose radically simplified forms revolutionized modern sculpture. American modernists were also represented, including works by John Graham, a Russian émigré artist who became an influential figure in the New York art scene.

Horter's interest extended to non-Western art forms, which were increasingly recognized by modern artists for their formal power and spiritual depth. He collected African sculpture and Native American artifacts. His interest in these areas was likely influenced by figures like the Parisian dealer Paul Guillaume, who was a major promoter of African art and modern painting, and Alfred Stieglitz, the photographer and gallerist who championed American modernists like Marsden Hartley, John Marin, Arthur Dove, and Georgia O'Keeffe, and who also exhibited African art at his gallery "291."

The Armory Show and Its Impact

The International Exhibition of Modern Art, famously known as the Armory Show, held in New York in 1913 (and subsequently traveling to Chicago and Boston), was a watershed moment for American art. It introduced a broad American audience to the radical developments in European art, including Fauvism, Cubism, and Futurism. Earl Horter was among the American artists whose work was included in this landmark exhibition. His participation, though perhaps overshadowed by the controversial European entries, placed him firmly within the currents of modernism that were beginning to reshape American artistic consciousness.

The Armory Show undoubtedly fueled Horter's passion for collecting. It provided a concentrated exposure to the very art he was beginning to acquire, and it legitimized, for some, the avant-garde movements that had previously been known only to a small circle of artists, critics, and collectors. For Horter, seeing these works and understanding their context likely reinforced his conviction in their importance.

A Champion of the Avant-Garde in Philadelphia

After his years in New York, Horter eventually resettled in Philadelphia. He brought with him not only his artistic practice but also his remarkable collection and his fervent belief in modern art. In a city that was often perceived as more conservative in its artistic tastes compared to New York, Horter became an important, if somewhat quiet, catalyst for modernism.

He shared his collection generously. In 1934, selections from his collection were exhibited at the Pennsylvania Museum of Art (now the Philadelphia Museum of Art) and the Arts Club of Chicago. These exhibitions provided a rare opportunity for the public and fellow artists in these cities to see firsthand major works of European modernism. Such exposure was invaluable in fostering a greater understanding and appreciation of these new artistic languages.

Horter also began to teach art in the 1930s. He held positions at the Philadelphia Museum School of Industrial Art (now the University of the Arts) and the Stella Elkins Tyler School of Fine Arts at Temple University. As an educator, he was able to directly influence a new generation of artists, sharing his technical knowledge as a printmaker and painter, and, importantly, exposing his students to the principles of modern art through the lens of his own collection and experience. His home, part of which he converted into a studio and gallery space, became a hub for artists and students interested in the avant-garde.

His role as a collector and educator in Philadelphia can be seen in parallel to other significant figures in the city, such as Albert C. Barnes, whose collection of modern and post-impressionist art, though assembled with a different philosophy and accessibility, also profoundly impacted the city's cultural landscape. Horter's approach was perhaps more artist-centric, driven by a fellow practitioner's understanding and admiration for the innovations of his peers.

The Great Depression and Its Toll

The Great Depression, which began in 1929 and extended through the 1930s, had a devastating impact on the American economy and, consequently, on the art world. Commercial art assignments, which had provided Horter with a steady income, dwindled. The financial strain forced him to make difficult decisions regarding his cherished art collection.

Beginning in the early 1930s, Horter was compelled to sell off significant portions of his collection to make ends meet. This was undoubtedly a painful process for a man who had poured so much passion and resources into assembling it. Works by Picasso, Braque, Duchamp, and others gradually left his possession, many finding their way into other private collections or, eventually, public museums. While he attempted to keep parts of the collection intact through loans and exhibitions, the economic realities were harsh.

Despite these financial hardships, Horter continued to create his own art and to teach. His commitment to art remained unwavering, even as he had to part with treasures that had defined a significant part of his life and identity as a connoisseur. The dispersal of his collection, while a personal loss, ultimately contributed to the broader dissemination of modern art, as these works became accessible to new audiences in different contexts.

Later Years and Continued Artistic Practice

Throughout the 1930s, even amidst financial difficulties and the sale of his collection, Earl Horter remained an active artist. His focus on urban landscapes continued, and his style evolved, absorbing more overtly modernist influences, likely deepened by his intimate, long-term engagement with the masterworks he had owned. His watercolors from this period are particularly noteworthy, displaying a fluidity and an expressive use of color that complemented his precise draftsmanship.

His teaching activities provided not only a source of income but also a means to stay engaged with the artistic community and to share his knowledge. He was respected by his students for his technical skill and his deep understanding of art history, particularly modern movements. His influence extended to artists like Arthur B. Carles, a Philadelphia modernist painter who was also a friend, and whose circle would have been aware of Horter's collection and artistic views. Other Philadelphia artists, such as Charles Demuth and Charles Sheeler, who became associated with the Precisionist movement, shared Horter's interest in industrial and urban subject matter, though their stylistic approaches diverged. Horter's engagement with the city's forms resonated with the broader American Scene painting and Precisionist trends of the era.

Earl Horter passed away on March 29, 1940, in Philadelphia, at the age of 59, due to a heart condition. He left behind a body of work that captured the spirit of his time and a legacy as one of America's pioneering collectors of modern art.

Legacy and Reappraisal

For many years after his death, Earl Horter's significance, particularly as a collector, was not widely recognized outside of specialized circles. However, scholarship in the late 20th century began to shed more light on his contributions. The culmination of this reappraisal was the landmark exhibition "Mad for Modernism: Earl Horter and His Collection," organized by the Philadelphia Museum of Art in 1999. Curated by Innis Howe Shoemaker, this exhibition brought together many of the key works that had once constituted Horter's remarkable collection, alongside examples of his own art.

The exhibition and its accompanying catalog provided a comprehensive overview of Horter's dual role as artist and collector. It revealed the extraordinary quality and range of his acquisitions, underscoring his prescient eye and his deep commitment to the avant-garde. Seeing masterpieces by Picasso, Braque, Duchamp, Gris, and Léger reunited under the umbrella of Horter's vision was a powerful testament to his impact. The exhibition also highlighted how Horter's own artwork was in dialogue with the modernism he so admired, showing an artist who was both a creator and a profound student of the art of his time.

Today, Earl Horter's own etchings and watercolors are held in the collections of major American museums, including the Philadelphia Museum of Art, the Detroit Institute of Arts, the Whitney Museum of American Art, and the Princeton University Art Museum. His works are appreciated for their technical finesse and their evocative portrayal of early 20th-century American urbanism.

His legacy as a collector is perhaps even more profound. By acquiring and exhibiting challenging modern art at a time when it was little understood in America, he played a vital role in educating public taste and influencing fellow artists. He was part of a small but crucial group of early American collectors, alongside figures like John Quinn, Walter Arensberg (another important Duchamp collector), and Lillie P. Bliss, whose efforts helped to establish the foundations for America's great museum collections of modern art.

Conclusion

Earl Horter's life was one of dedicated engagement with art, both as a creator and a connoisseur. From his beginnings as a self-taught engraver to his achievements as a respected printmaker and watercolorist, he consistently demonstrated a high level of skill and a keen observational eye. His depictions of the urban landscapes of Philadelphia and New York offer valuable artistic records of a transformative period in American history.

Yet, it is his role as a pioneering collector of modern art that arguably constitutes his most enduring legacy. With limited means but an unerring eye, he assembled a collection of avant-garde masterpieces that was among the finest in America. His willingness to share this collection through exhibitions and his teaching helped to foster an appreciation for modernism in Philadelphia and beyond. Earl Horter's story is a compelling reminder that passion, vision, and dedication can enable individuals to make significant contributions to the cultural landscape, shaping the course of art history in ways that continue to resonate. His dual identity as an artist and a collector provides a rich lens through which to understand the complex and exciting art world of the early twentieth century.