Samuel Halpert stands as a significant, if sometimes underappreciated, figure in the narrative of early American modernism. A painter whose career bridged the vibrant art scenes of Paris and New York, Halpert was instrumental in absorbing and translating European avant-garde ideas for an American context. His life and work reflect the dynamic cultural exchanges of the early twentieth century, a period of radical artistic innovation. Through his canvases, his teaching, and his association with key institutions and personalities, Halpert contributed to the burgeoning modernist movement in the United States, leaving behind a body of work that captures the spirit of his time with sensitivity and a distinctive stylistic flair.

Early Life and Artistic Awakening

Born in 1884 in Białystok, a city then part of the Russian Empire and now located in northeastern Poland, Samuel Halpert's journey into the art world began in an environment far removed from the cultural capitals he would later inhabit. At the tender age of five, his family emigrated to the United States, settling in New York City. This immigrant experience, shared by many artists and intellectuals of his generation, undoubtedly shaped his perspective and resilience. New York, a burgeoning metropolis, offered a stark contrast to his birthplace and provided the initial backdrop for his artistic inclinations.

His formal artistic training commenced in New York. He initially enrolled at the National Academy of Design, a bastion of academic tradition. It was here he encountered Leon Kroll, an influential painter and instructor. However, this early educational experience was not entirely smooth; Kroll, perhaps failing to see the nascent modernist spark in Halpert, reportedly advised him that he lacked talent and should consider a different path. Such discouragement, however, did not deter Halpert. Instead, it may have fueled his determination to seek out more progressive avenues for artistic development. He also spent time at the Ferrer Center (Francisco Ferrer y Guardia Association), a more radical, anarchist-influenced educational institution in New York that attracted many avant-garde artists and thinkers, including Robert Henri and George Bellows, and provided a more liberal environment for artistic exploration.

The Parisian Crucible: Immersion in the Avant-Garde

Recognizing the limitations of the American art scene for an aspiring modernist, Halpert, like many of his ambitious contemporaries, set his sights on Paris, the undisputed epicenter of the art world in the early 1900s. He arrived in the French capital around 1902, embarking on a period of intense study and immersion that would profoundly shape his artistic vision. Paris was a melting pot of revolutionary ideas, with artists challenging established norms and forging new visual languages.

During his time in Paris, which extended for nearly a decade with intermittent returns to New York, Halpert absorbed the influences of various modern movements. He was particularly drawn to the work of Post-Impressionists, most notably Paul Cézanne. Cézanne's emphasis on underlying geometric structure, his method of building form through color, and his departure from traditional perspective had a lasting impact on Halpert's approach to composition and representation. The vibrant, non-naturalistic colors and expressive brushwork of the Fauvists, led by Henri Matisse, André Derain, and Maurice de Vlaminck, also captivated him. This exposure to Fauvism encouraged Halpert to experiment with bold color palettes and simplified forms, moving away from the more subdued tones of academic painting.

Halpert's linguistic abilities, being fluent in both French and English, facilitated his integration into the Parisian art community. He frequented the studios and salons where artists and intellectuals congregated, engaging in discussions and forging valuable connections. He became acquainted with prominent figures such as the sculptor Jacob Epstein, with whom he developed a close friendship. He also formed friendships with Henri Rousseau, whose "naïve" style was admired by the avant-garde, and reportedly with Matisse himself. He would have been aware of the groundbreaking work of Pablo Picasso and Georges Braque as they developed Cubism, even if his own work did not fully embrace its analytical fragmentation. The artistic ferment of Paris, with its constant experimentation and intellectual exchange, provided an unparalleled education for Halpert. He also studied at various French academies, further honing his skills while steeping himself in the modernist ethos.

Return to America and the Armory Show

Halpert returned to the United States equipped with a modernist sensibility forged in Paris. He brought back not only new techniques and aesthetic principles but also a cosmopolitan perspective. His re-entry into the American art scene coincided with a period of growing interest in modern art, albeit one met with considerable public and critical resistance.

A pivotal moment in the introduction of modern art to America was the International Exhibition of Modern Art, famously known as the Armory Show, held in New York City in 1913. This landmark exhibition, organized by artists like Arthur B. Davies, Walt Kuhn, and Walter Pach, showcased a vast array of European avant-garde art alongside works by progressive American artists. Samuel Halpert was among the American artists whose work was included in this transformative event. His participation, though perhaps not as sensational as that of European artists like Marcel Duchamp, whose Nude Descending a Staircase, No. 2 caused a scandal, nonetheless positioned him firmly within the modernist camp in America. The Armory Show was a watershed, shocking and educating the American public and galvanizing American artists to engage more directly with international modernism.

Artistic Style and Major Themes

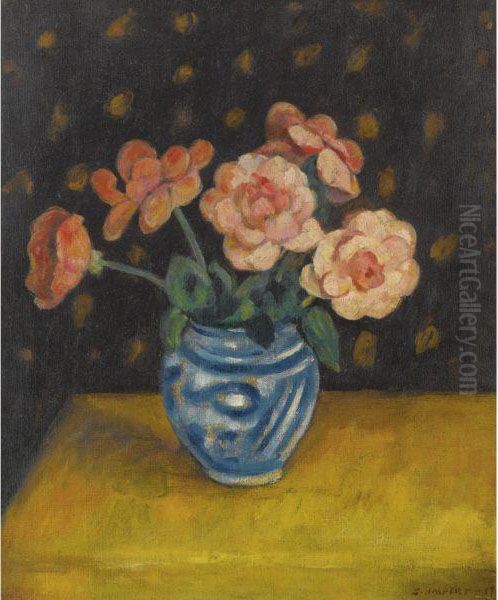

Samuel Halpert's artistic style is characterized by its synthesis of European modernist influences, particularly Post-Impressionism and Fauvism, adapted to an American sensibility. He is often described as an Impressionist, but his work extends beyond the fleeting light effects of traditional Impressionism, incorporating a more structured approach to form and a bolder use of color.

A hallmark of Halpert's style is his use of large, distinct blocks of color and strong, often dark, outlines. This technique, reminiscent of Cézanne's constructive brushstrokes and the decorative patterning of the Fauves, allowed him to create compositions that were both visually striking and formally coherent. He skillfully balanced representation with a modernist concern for the picture plane, emphasizing the two-dimensional nature of the canvas while still conveying a sense of depth and space.

His subject matter was diverse, encompassing landscapes, cityscapes, interiors, and still lifes. He was particularly adept at capturing the character of his surroundings, whether the bustling energy of New York City or the tranquil beauty of rural landscapes, such as those he painted in Ogunquit, Maine, a popular artists' colony. His cityscapes often focused on iconic structures, rendered with a modernist appreciation for their geometric forms and dynamic presence. In his landscapes and interiors, he explored the interplay of light and color, creating scenes that were both evocative and carefully composed. He sought to convey the essence of his subjects rather than a literal transcription, using color and form to express mood and atmosphere.

Key Works: A Closer Look

Several of Samuel Halpert's paintings stand out as representative of his artistic achievements and stylistic concerns.

Brooklyn Bridge (1913): Created in the same year as the Armory Show, this painting, now in the collection of the Whitney Museum of American Art, is one of Halpert's most iconic works. It depicts the famous New York landmark with a modernist sensibility, emphasizing its monumental structure and the dynamic interplay of its architectural elements. Halpert uses bold outlines and simplified forms, with a palette that, while not overtly Fauvist, demonstrates a confident use of color to define mass and space. The painting captures the bridge not just as an engineering marvel but as a symbol of modern urban life, a theme explored by many artists of the period, including John Marin and Joseph Stella.

Summer: While specific details of a single work titled Summer are less consistently documented than Brooklyn Bridge, Halpert frequently painted scenes evoking the warmth and vibrancy of the season. These works typically feature lush landscapes or leisurely outdoor scenes, rendered with his characteristic use of strong color and defined forms. They reflect his ability to capture the sensory experience of nature, filtered through a modernist lens.

Cottage Interior, Ogunquit (1929): This painting, housed in the Metropolitan Museum of Art, showcases Halpert's skill in depicting intimate interior spaces. Created towards the end of his life, it reflects a mature handling of color and composition. The scene is likely from his time in Ogunquit, Maine, a haven for artists. The work demonstrates his interest in the interplay of light and shadow within an enclosed space, and the arrangement of objects to create a harmonious and visually engaging composition. Artists like Édouard Vuillard and Pierre Bonnard of the Nabis group had earlier explored similar intimate interior themes with a focus on pattern and color, and echoes of their concerns can be seen.

The Flatiron Building: Another of Halpert's New York cityscapes, this work captures the distinctive triangular form of one of the city's early skyscrapers. Like his Brooklyn Bridge, it shows his fascination with modern urban architecture. He employs loose brushwork and a vibrant palette to convey the energy of the city and the building's imposing presence, demonstrating a fusion of Impressionistic light effects with a more structured, Post-Impressionist approach.

Farm Interior (c. 1924): This painting, in the collection of the Smithsonian American Art Museum, offers a glimpse into a rustic interior. It showcases Halpert's ability to find beauty and interest in everyday scenes. The composition is carefully structured, with attention to the geometric shapes of the furniture and architectural elements, and the colors are rich and evocative, typical of his mature style.

After the Siesta (1925): This work, currently in a private collection, likely depicts a figure in a relaxed, intimate setting. It would exemplify Halpert's interest in genre scenes and his ability to convey mood through color and composition. The title itself suggests a quiet, contemplative moment, a recurring theme in modernist art that sought to capture subjective experience.

These works, among others, demonstrate Halpert's consistent engagement with modernist principles, his skillful use of color and form, and his ability to imbue diverse subjects with a distinct personal vision.

Marriage to Edith Gregor Halpert and the Downtown Gallery

Samuel Halpert's personal life was significantly intertwined with his artistic career, particularly through his marriage to Edith Gregor Fein (later Edith Gregor Halpert). They married in 1918. Edith was a formidable figure in her own right, who would become one of America's most influential art dealers. Their relationship, however, was complex and reportedly fraught with tension. Sources indicate that financial pressures, personality differences, and Halpert's struggles with tinnitus (a ringing in the ears, later attributed to childhood meningitis) contributed to marital strain. There were also suggestions of Halpert's jealousy regarding Edith's burgeoning success and earning capacity. The couple made several trips to France, partly in an attempt to salvage their relationship, before eventually returning to New York.

Despite these personal difficulties, their partnership had a profound impact on the American art world. In 1926, Edith Gregor Halpert opened the Downtown Gallery in Greenwich Village, New York. It was one of the first commercial galleries dedicated to promoting contemporary American art and American folk art. Samuel Halpert was supportive of this venture, and his connections and artistic knowledge likely played a role in its early stages.

The Downtown Gallery became a crucial platform for many leading American modernists, including Stuart Davis, Charles Sheeler, Yasuo Kuniyoshi, Ben Shahn, and later, Jacob Lawrence and Horace Pippin. Edith Halpert had a keen eye for talent and a progressive vision, championing artists who were often overlooked by more established institutions. She was also a pioneer in exhibiting American folk art alongside contemporary art, recognizing its aesthetic value and its importance to the American cultural identity. While Samuel Halpert's direct involvement in the day-to-day operations of the gallery may have lessened over time, especially as his own career took him to Detroit, the gallery's ethos and success were undoubtedly shaped by their shared immersion in the modernist art world.

Later Career, Detroit, and Artistic Community

In the later part of his career, Samuel Halpert's focus shifted somewhat towards teaching and institutional involvement. In 1927, he was appointed head of the painting department at the art school of the Detroit Society of Arts and Crafts (now the College for Creative Studies). This position was reportedly secured through a recommendation from John Sloan, a prominent artist associated with the Ashcan School and a key figure in American modernism.

His move to Detroit placed him in a different artistic milieu than New York or Paris, but he continued to paint and contribute to the local art scene. He fostered connections with important collectors in Detroit, such as Robert Tannahill, who was a significant patron of modern art. In this teaching role, Halpert would have had the opportunity to impart his knowledge and modernist principles to a new generation of artists, extending his influence beyond his own studio practice.

Throughout his career, Halpert remained an active participant in the broader artistic community. He was a member of the Society of Independent Artists, an organization founded in 1916 (with figures like Walter Arensberg, Katherine Sophie Dreier, and Marcel Duchamp involved) to provide exhibition opportunities for artists outside the traditional jury system, reflecting the spirit of the Parisian Salon des Indépendants. He was also involved with the Whitney Studio Club, a precursor to the Whitney Museum of American Art, founded by Gertrude Vanderbilt Whitney to support progressive American artists. These affiliations underscore his commitment to the modernist cause and his engagement with its key institutions.

He maintained friendships and professional relationships with a wide range of artists. His early camaraderie with Jacob Epstein in Paris continued to be significant. His mentorship of a young Man Ray, even though Halpert himself did not embrace Dadaism, speaks to his open-mindedness and his respected position among younger artists. Man Ray, who would become a leading figure in Dada and Surrealism, valued Halpert's guidance during his formative years.

Legacy and Critical Reception

Samuel Halpert's career was relatively short; he passed away in Detroit in 1930 at the age of 45. Despite his significant contributions as an early adopter and disseminator of modernist ideas in America, his reputation has sometimes been overshadowed by more flamboyant or radically innovative contemporaries. However, a closer examination of his work and career reveals an artist of considerable talent and importance.

Academic and critical assessment acknowledges Halpert as a key pioneer of American modernism. His ability to absorb the lessons of Cézanne and the Fauves and to translate them into a personal style that resonated with American subjects was a significant achievement. He was part of a crucial generation of artists who helped to shift the center of the art world from Paris to New York, a process that would culminate in the rise of Abstract Expressionism after World War II with artists like Jackson Pollock, Willem de Kooning, and Mark Rothko.

His paintings are held in the collections of major American museums, including the Whitney Museum of American Art, the Metropolitan Museum of Art, and the Smithsonian American Art Museum, attesting to their enduring quality and historical significance. While he may not have achieved the same level of fame as some of his peers, his work is valued for its lyrical color, strong composition, and its sensitive depiction of early 20th-century American life through a modernist lens.

The influence of the Downtown Gallery, co-founded in spirit if not in daily management with Edith Halpert, also forms part of his indirect legacy. The gallery's groundbreaking promotion of American modern and folk art had a lasting impact on the development of American art collecting and museum acquisitions. Edith Halpert's inclusive and diverse vision, which Samuel undoubtedly shared to some extent, helped to broaden the definition of American art and to champion artists from various backgrounds.

Conclusion: An Enduring Contribution

Samuel Halpert was more than just a painter; he was a vital conduit for modernist ideas, a dedicated teacher, and an active participant in the artistic communities of his time. From the vibrant streets of Białystok to the bohemian studios of Paris and the burgeoning art scenes of New York and Detroit, his life was a testament to the transformative power of art and the relentless pursuit of a modern vision.

His paintings, with their harmonious colors, bold forms, and thoughtful compositions, offer a unique window into the early decades of the twentieth century. They reflect an artist grappling with the new visual languages of modernism while remaining grounded in a deep appreciation for the world around him. While his career was cut short, Samuel Halpert's legacy endures through his art and his role in shaping the course of American modernism, securing his place as a pivotal figure in the rich tapestry of American art history. His work continues to engage viewers with its quiet strength and its eloquent expression of a world undergoing profound artistic and cultural change.