Jean Béraud stands as one of the most perceptive and detailed visual chroniclers of Parisian life during the vibrant era known as the Belle Époque. Born on January 12, 1849, and passing away on October 4, 1935, this French painter captured the spirit, energy, and social nuances of his time with remarkable acuity. Though often associated with Impressionism due to his subject matter, Béraud forged a unique path, blending the meticulous finish of academic tradition with a keen observation of modern urban existence. His canvases offer an unparalleled window into the bustling boulevards, chic cafés, intimate salons, and everyday moments that defined Paris in the late 19th and early 20th centuries.

Early Life and Artistic Formation

Jean Béraud's life began not in Paris, but in St. Petersburg, Russia. His father, also named Jean Béraud, was a sculptor working on the St. Isaac's Cathedral. Tragically, his father passed away when Jean was only four years old. Following this loss, his mother, Geneviève Eugénie Jacquin, moved the family, including Jean and his twin sister Mélanie, back to Paris. This return to the French capital would prove definitive for Béraud's future artistic focus.

He received his education at the prestigious Lycée Bonaparte (now Lycée Condorcet). Initially, Béraud pursued studies in law, a common path for young men of his social standing. However, the call of art proved stronger. His formal artistic training commenced around 1871-1872, following the disruptions of the Franco-Prussian War and the Paris Commune. He enrolled at the renowned École des Beaux-Arts, the bastion of French academic art.

Crucially, Béraud entered the studio of Léon Bonnat. Bonnat was a highly respected painter, known for his portraiture and historical scenes, executed with a sober realism and strong draftsmanship influenced by Spanish masters like Velázquez. Studying under Bonnat provided Béraud with a rigorous foundation in drawing, composition, and the traditional techniques valued by the Academy. This training instilled in him a commitment to careful rendering and detail that would remain a hallmark of his style throughout his career, setting him apart from many of his Impressionist contemporaries.

Emergence as a Parisian Chronicler

Béraud made his debut at the official Paris Salon in 1872. The Salon was the primary venue for artists to gain recognition and patronage in France at the time. His early submissions primarily consisted of portraits, reflecting the influence of his teacher, Bonnat, and the conventional path for aspiring artists. While competent, these initial works did not immediately catapult him to fame.

The turning point came in 1876 with his painting Le Retour de l'enterrement (often translated as On the Way Back from the Funeral or Return from the Funeral). Exhibited at the Salon, this work garnered significant attention and marked Béraud's shift towards the subject matter that would define his career: contemporary Parisian life. The painting depicts mourners dispersing after a funeral, capturing a specific social ritual with sharp observation and a hint of narrative. It showcased his ability to render figures and settings realistically while subtly commenting on social customs and individual reactions within a crowd.

This success encouraged Béraud to further explore the multifaceted life of Paris. He abandoned historical and mythological subjects almost entirely, dedicating himself to capturing the city's streets, public spaces, and social gatherings. He became a familiar figure sketching outdoors and observing the flow of urban life, translating his observations into detailed, engaging paintings that resonated with the public and critics alike.

Artistic Style: Bridging Traditions

Jean Béraud's artistic style occupies a fascinating space between the established academic tradition and the burgeoning Impressionist movement. He never fully embraced the broken brushwork, dissolution of form, or primary focus on fleeting light effects that characterized painters like Claude Monet or Camille Pissarro. Instead, he retained the precise draftsmanship and smooth finish learned under Bonnat. His figures are clearly defined, clothing and architectural details are rendered with meticulous care, and his compositions often have a strong narrative or anecdotal quality.

However, Béraud was undeniably influenced by Impressionism, particularly in his choice of subject matter. Like Edgar Degas or Gustave Caillebotte, he was drawn to modern life: the dynamism of the boulevards, the social interactions in cafés and theaters, the leisure activities of the bourgeoisie. He shared the Impressionists' interest in capturing the specific atmosphere of a place and moment. While his technique remained more traditional, his sensitivity to light, particularly the artificial light of interiors and gaslit streets, reflects contemporary concerns.

A distinctive element of Béraud's work is its subtle wit and observational humor. He often included small details or character types that offered a gentle commentary on social manners, vanities, and the bustling energy of Parisian society. His paintings are not just records; they are character studies and social vignettes, delivered with a sophisticated, worldly eye. This blend of academic skill, modern subject matter, and insightful observation created a style that was both accessible and highly distinctive.

Iconic Parisian Scenes

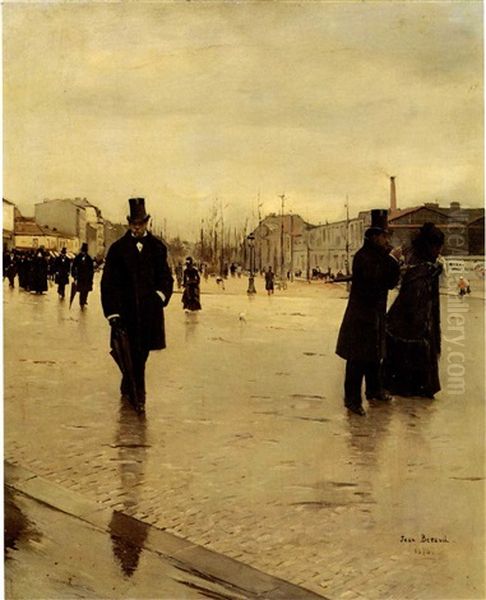

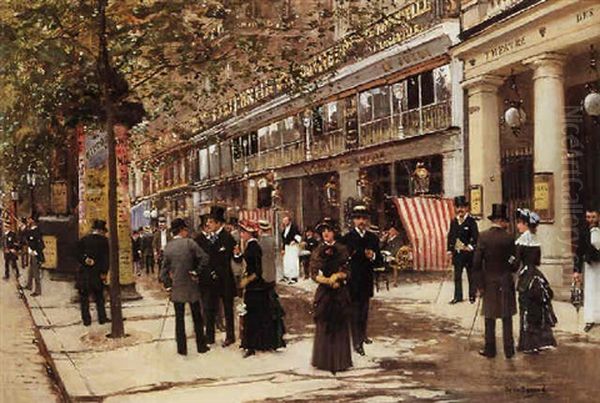

Béraud became synonymous with depictions of specific Parisian locales and activities. His canvases teem with the life of the grand boulevards, particularly the Champs-Élysées and the Boulevard des Italiens. He captured the endless parade of pedestrians, horse-drawn carriages (and later, the occasional early automobile), fashionable strollers, street vendors, and uniformed officials. These street scenes are remarkable for their detail, conveying the energy and social mix of these vital urban arteries.

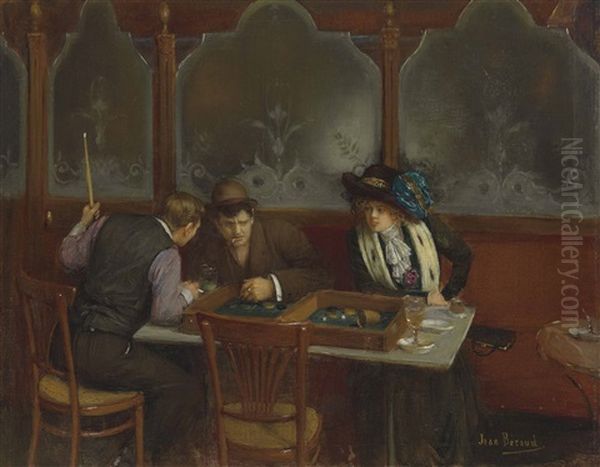

Café society was another favorite subject. Béraud depicted patrons inside famous establishments like the Café de Paris or Tortoni, as well as those seated at outdoor terraces, observing the world go by. These paintings capture the importance of the café as a social hub, a place for conversation, business, and simply being seen. He masterfully rendered the interplay of natural and artificial light within these spaces, highlighting the textures of wood paneling, marble tabletops, and mirrored walls.

The world of entertainment also drew his attention. Béraud painted scenes set in theaters, capturing the elegance of audiences during intermissions, the crowded foyers, and sometimes glimpses of the stage. Works like La Loge (The Theater Box) or Sortie de l'Opéra (Leaving the Opera) depict the fashionable crowds and social rituals associated with Parisian nightlife. He also painted scenes of balls, soirées, and private gatherings, offering insights into the social life of the upper and middle classes.

Key Representative Works

Several paintings stand out as quintessential examples of Béraud's oeuvre. Le Retour de l'enterrement (1876) remains significant as his breakthrough piece, noted for its realistic depiction of a contemporary social scene and its subtle emotional undertones.

La Pâtisserie Gloppe (circa 1889) is another celebrated work, depicting the interior of a fashionable pastry shop on the Champs-Élysées. It exemplifies Béraud's skill in rendering elegant interiors, fashionable attire, and social interactions. The painting captures a moment of bourgeois leisure, showcasing the delights and social customs of the era with meticulous detail and charm.

His numerous depictions of the Champs-Élysées, often simply titled Les Champs-Élysées, capture the grandeur and activity of this iconic avenue in various weather conditions and times of day. These works are filled with anecdotal details, showcasing the diverse mix of people promenading and socializing. Similarly, paintings titled Le Boulevard des Capucines or Boulevard Montmartre bring other famous Parisian thoroughfares to life.

Le Café or specific scenes like Au Café show his mastery of interior scenes, capturing the ambiance of these establishments. La Salle de Rédaction du Journal des Débats (The Editorial Room at the Journal des Débats, 1889) offers a fascinating glimpse into the world of journalism, depicting prominent figures of the time in a specific, detailed setting. These works demonstrate his ability to function almost as a photojournalist, documenting specific places and people.

The Belle Époque Through Béraud's Eyes

Jean Béraud's work provides an invaluable visual document of the Belle Époque (roughly 1871-1914). This period in French history was characterized by relative peace, economic prosperity, technological innovation, and a flourishing arts scene. Béraud captured the optimism and dynamism of this era, but also its underlying social structures and complexities.

His paintings illustrate the rise and consolidation of the bourgeoisie, showcasing their fashions, leisure activities, and social rituals. From elegant afternoons at the patisserie to evenings at the opera, Béraud depicted the comfortable lifestyle enjoyed by the middle and upper classes. He meticulously recorded the details of dress, décor, and transportation, offering historians rich visual information about the material culture of the time.

While generally celebratory of Parisian life, his work sometimes contains subtle social commentary. The juxtaposition of different social types within a single scene, or the occasional focus on less glamorous aspects of the city (though less frequent than his depictions of high life), hints at the social diversity and occasional tensions beneath the glittering surface of the Belle Époque. He captured the city in transformation, documenting a world poised between tradition and modernity.

Contemporaries and the Art World

Béraud navigated the complex Parisian art world of his time, interacting with artists from various circles. While distinct from the core Impressionists, he shared their interest in modern life and frequented similar social spaces. He was known to socialize with figures like Edgar Degas, whose depictions of dancers, cafés, and racetracks paralleled some of Béraud's own interests, albeit with a different stylistic approach and psychological depth. He likely knew Auguste Renoir, though Renoir's focus shifted more towards portraiture and idyllic scenes later in his career.

Béraud's detailed realism and focus on fashionable society align him somewhat with other painters popular during the Belle Époque, such as James Tissot and Alfred Stevens, who also depicted elegant social scenes, though often with a different sensibility. He can also be compared to Gustave Caillebotte, who shared an interest in depicting the modern city and its inhabitants with a degree of realism, but often employed more daring perspectives influenced by photography.

His contemporaries also included artists focused on different aspects of Parisian life or employing different styles. Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec famously captured the gritty, vibrant nightlife of Montmartre cabarets and brothels with a bold, linear style very different from Béraud's polished finish. The foundational Impressionists like Claude Monet and Camille Pissarro were primarily focused on landscape and the effects of light outdoors. Édouard Manet, a key precursor to Impressionism, had pioneered modern life subjects earlier, influencing many artists, including Béraud. Other society painters like Giovanni Boldini offered flamboyant portraits of the era's elite. Béraud also knew writers, famously serving as a second for his friend Marcel Proust in a duel in 1897. He was clearly an active participant in the cultural life of Paris.

Involvement in Art Movements and Societies

While not strictly adhering to a single movement, Béraud's work touches upon several artistic currents of his time. His detailed observation and focus on contemporary social reality connect him to the broader movement of Realism and Naturalism, particularly evident in works depicting specific social types or environments, such as Les Fous (The Madmen) or La Salle des filles au dépôt (The Girls' Room at the Depot).

His relationship with Impressionism was one of proximity and influence rather than full participation. He absorbed the Impressionist interest in modern subjects and capturing the atmosphere of the moment but maintained his academic technique. He exhibited regularly at the official Paris Salon (Salon des Artistes Français), where he achieved considerable success, winning medals in 1882 and 1883. This contrasted with the Impressionists who largely rejected the Salon and organized their own independent exhibitions.

However, Béraud was also involved in efforts to reform the art establishment. He became a founding member and later Vice President of the Société Nationale des Beaux-Arts (SNBA) in 1890. This society was formed as a more liberal alternative to the traditional Salon, aiming to showcase a wider range of contemporary art. Béraud exhibited with the SNBA from its inception until 1929. His participation highlights his position within the art world – respected enough to be part of official structures but also open to newer currents. He also achieved official recognition, winning a gold medal at the Exposition Universelle (World's Fair) in Paris in 1889 and being awarded the Légion d'honneur in 1894.

The Turn to Religious Themes

Around the 1890s, Béraud surprised the Parisian art world by turning his attention to religious subjects. However, he approached these themes in a highly unconventional manner, often placing biblical figures and events in contemporary Parisian settings. This approach was controversial and generated considerable debate.

Works like La Madeleine chez le Pharisien (Mary Magdalene in the House of the Pharisee, 1891) depicted Christ and his followers dressed in modern attire, interacting within a contemporary Parisian interior. Similarly, his Descente de Croix (Descent from the Cross, 1892) and Le Chemin de la Croix (The Way of the Cross) transposed sacred events into modern urban contexts.

This modernization of religious iconography was seen by some as innovative and relevant, bringing timeless stories into the present day. Others found it shocking, irreverent, or even blasphemous. The juxtaposition of sacred figures with recognizable contemporary Parisians and settings challenged traditional notions of religious art. Despite the controversy, these works demonstrated Béraud's willingness to experiment and engage with complex themes, even late in his established career.

Later Life and Legacy

In the later decades of his career, particularly after the turn of the century, Jean Béraud's artistic production gradually decreased. He became increasingly involved in the administrative side of the art world, serving on committees and juries for exhibitions, including those of the Société Nationale des Beaux-Arts. His reputation as a quintessential painter of Parisian life was firmly established.

He continued to live and work in Paris, witnessing the profound changes brought by the new century, including the advent of the automobile (which began to appear in his later street scenes) and the trauma of World War I, which effectively ended the Belle Époque era he had so vividly documented.

Jean Béraud died in Paris on October 4, 1935, at the age of 86. He was buried in the Montmartre Cemetery, a fitting final resting place in the city he had spent his life observing and painting.

His legacy endures primarily through his captivating depictions of Belle Époque Paris. While perhaps not a radical innovator on the scale of the leading Impressionists or Post-Impressionists, Béraud holds a unique and important place in French art history. His paintings offer an unparalleled visual record of a specific time and place, rendered with technical skill, charm, and keen observation. They continue to delight viewers with their intricate details, lively atmosphere, and evocative portrayal of Parisian society during one of its most celebrated periods. He remains the ultimate painter-chronicler of the Parisian Belle Époque.

Conclusion

Jean Béraud masterfully captured the pulse of Paris during the Belle Époque. His unique blend of academic precision and modern sensibility allowed him to create vivid, detailed tableaus of urban life. From the bustling energy of the grand boulevards and the intimate ambiance of cafés to the elegance of society gatherings, his work provides an enduring and enchanting window onto a bygone era. More than just a painter, Béraud was a historian in oils, preserving the look, feel, and social fabric of late 19th and early 20th-century Paris for generations to come. His paintings remain beloved for their charm, detail, and invaluable documentation of the City of Light during a time of vibrant transformation.