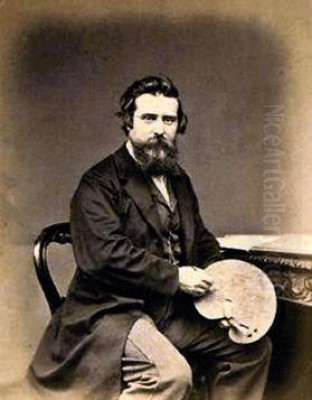

Edward Angelo Goodall (1819-1908) stands as a significant, if sometimes overlooked, figure in the rich tapestry of 19th-century British art. A prolific watercolourist and intrepid traveller, Goodall dedicated his long career to capturing the landscapes, architecture, and peoples of diverse and often remote regions. His work, characterized by its meticulous detail, subtle colouring, and atmospheric sensitivity, provides not only aesthetic pleasure but also invaluable historical and ethnographic records of a world undergoing rapid change. Born into an artistic dynasty, Goodall's life was one of constant exploration, both geographically and artistically, leaving behind a legacy that continues to inform and inspire.

Early Life and Artistic Lineage

Edward Angelo Goodall was born in London on June 8, 1819. He was the eldest son of Edward Goodall (1795-1870), a highly respected line engraver renowned for his skillful interpretations of works by leading artists of the day, most notably J.M.W. Turner. The Goodall household was steeped in art; Edward Angelo's younger brothers, Frederick Goodall (1822-1904), Walter Goodall (1830-1889), and his sisters, Eliza Goodall (1827-1916) and Frances Goodall (later known as Frances Todd, dates vary), also pursued artistic careers. Frederick, in particular, would achieve considerable fame as a painter, especially for his Orientalist scenes, becoming a Royal Academician.

This familial environment provided Edward Angelo with an early and immersive artistic education. He initially trained in his father's engraving studio, mastering the precision and discipline inherent in that craft. This foundational training undoubtedly contributed to the meticulous detail and fine draughtsmanship that would later characterize his watercolours. Alongside this practical instruction, he received a formal education at the University School, London.

From a young age, Goodall displayed a remarkable aptitude for drawing and painting. He was particularly drawn to the medium of watercolour, which was then enjoying a golden age in Britain, championed by artists like J.M.W. Turner himself, David Cox, and Peter De Wint. By his teenage years, Goodall was already producing accomplished works, demonstrating a keen eye for observation and a burgeoning talent for capturing the nuances of light and atmosphere. His early subjects were often local landscapes and architectural studies, honing the skills that would serve him so well in his later travels.

The Guiana Expedition: A Formative Journey

A pivotal moment in Goodall's early career came in 1841. At the young age of twenty-two, he was appointed as the official artist to the British government's expedition to Guiana (now Guyana). This expedition, led by the Prussian-born explorer and naturalist Sir Robert Hermann Schomburgk, aimed to survey and define the boundaries of British Guiana. For Goodall, this was an extraordinary opportunity to venture far beyond the familiar landscapes of Britain and immerse himself in the exotic flora, fauna, and indigenous cultures of South America.

Over the course of nearly four years, from 1841 to 1844 (some sources state 1842-1845), Goodall diligently documented the expedition's findings. He produced a vast number of watercolours depicting the lush tropical rainforests, majestic rivers, unique wildlife, and the various Amerindian tribes encountered, such as the Macushi, Wapisiana, and Arecuna peoples. His works from this period are remarkable for their scientific accuracy and ethnographic sensitivity. He captured not only the physical appearance of the plants and animals but also the daily lives, customs, and dwellings of the indigenous communities with a respectful and observant eye.

These Guiana watercolours were more than mere illustrations; they were sophisticated artistic creations that conveyed the vibrant colours and unique atmosphere of the region. Many of these works, including detailed studies of palm trees and other botanical specimens, are now housed in prestigious collections such as the British Library and the Wellcome Collection in London, serving as vital historical and botanical records. The experience profoundly influenced Goodall, broadening his artistic horizons and instilling in him a lifelong passion for travel and the depiction of foreign lands. His sketches of indigenous peoples were later exhibited in Paris and India, highlighting their international significance.

Artistic Style and Preferred Media

Edward Angelo Goodall was pre-eminently a watercolourist, although he also worked in oils. His style is often described as delicate, restrained, and meticulous, with a strong emphasis on accurate draughtsmanship and a subtle, harmonious palette. He possessed a remarkable ability to render complex architectural details and the varied textures of landscapes with precision, yet his works rarely feel stiff or overworked. Instead, they often convey a sense of calm and an appreciation for the play of light and shadow.

His early training as an engraver likely contributed to his careful handling and attention to detail. Unlike some of his more flamboyantly Romantic contemporaries, Goodall's approach was generally more topographical and descriptive, yet imbued with a quiet poetry. He particularly excelled at capturing the quality of light in different climates, from the humid haze of the tropics to the clear, bright light of the Mediterranean and the more diffuse light of Northern Europe.

While his brother Frederick Goodall became known for grander, often more narrative-driven Orientalist oil paintings, Edward Angelo's strength lay in the immediacy and intimacy of watercolour. He was a master of traditional watercolour techniques, using transparent washes to build up form and atmosphere. His depictions of architecture, whether ancient Egyptian temples, Venetian palaces, or Moroccan mosques, were rendered with an understanding of their structure and historical context, often populated with small figures that added scale and a sense of daily life. His landscapes, too, were carefully composed, drawing the viewer into the scene through well-judged perspectives and a balanced distribution of elements.

The Crimean War: Artist as Correspondent

The mid-1850s saw Goodall embark on another significant venture, this time as a war artist. In 1854-1855, he was commissioned by the Illustrated London News, a pioneering publication that brought visual reportage to a wide audience, to cover the Crimean War. This was a challenging and often dangerous assignment, requiring him to work under difficult conditions close to the front lines.

Goodall's role was to provide sketches and watercolours that could be translated into wood engravings for publication in the newspaper. He witnessed and documented key events of the conflict, including the aftermath of the Battle of Balaclava, the Battle of the Alma, and the lengthy Siege of Sevastopol. His drawings provided the British public with vivid, firsthand impressions of the war, depicting not only the battles and military operations but also the conditions of the soldiers, the landscapes of the Crimea, and the devastating impact of the conflict.

This experience further honed his skills in rapid sketching and capturing the essence of a scene under pressure. His Crimean works, like those of other artists such as William Simpson (known as "Crimean Simpson"), played an important role in shaping public perception of the war and demonstrated the growing power of visual journalism. These works stand as a testament to his courage and his ability to adapt his artistic talents to demanding circumstances.

Travels in Egypt and the Lure of the Orient

Following the Crimean War, Goodall's artistic focus increasingly turned towards the Middle East and North Africa, a region that held a powerful allure for many Victorian artists and writers, part of the broader cultural phenomenon known as Orientalism. His interest in Egypt may have been further stimulated by his father's own engagement with Egyptology.

Goodall made several extended trips to Egypt, beginning in the late 1850s and continuing into the 1870s. He was captivated by the monumental ancient ruins, the vibrant street life of Cairo, and the timeless landscapes of the Nile. He produced a significant body of work depicting the temples of Karnak and Luxor, the pyramids and Sphinx at Giza, and scenes of daily life along the river. Works such as Sphinx, near Sakkara and Interior of Mosque of Sultan Hassan, Cairo are representative of his Egyptian oeuvre. The former often combined archaeological accuracy with a sense of mystery, sometimes incorporating biblical or historical narratives, while the latter showcased his skill in rendering complex Islamic architecture and the interplay of light within grand interiors.

His Egyptian watercolours were highly sought after, appealing to a public fascinated by the "Orient." He shared this interest with contemporaries like David Roberts, whose lithographs of Egypt and the Holy Land had been immensely popular, and John Frederick Lewis, who lived in Cairo for many years and whose detailed depictions of Egyptian life were highly influential. Goodall's approach, while sharing the thematic concerns of these artists, often retained his characteristic subtlety and focus on atmospheric effect. He was less inclined towards the overtly romanticized or exoticized portrayals of some Orientalist painters, often presenting a more direct, though still picturesque, vision. Other artists exploring similar themes included Carl Haag, a German-born painter who also spent considerable time in Egypt.

Other Travels and Later Career

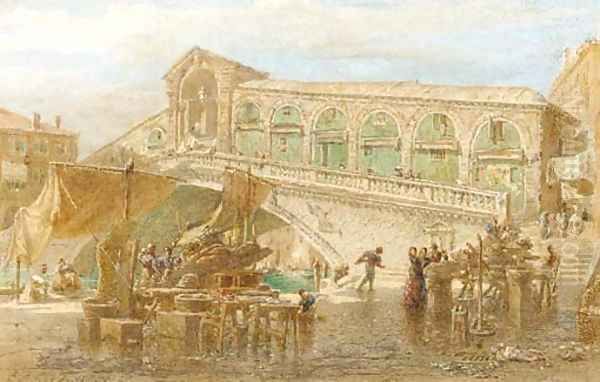

Beyond Guiana, the Crimea, and Egypt, Edward Angelo Goodall's wanderlust took him to many other parts of the world. He travelled extensively throughout Europe, visiting Italy (especially Venice, a perennially popular subject for British artists since Canaletto and later Turner), Spain, Portugal, and France. He also ventured into Morocco, capturing the distinctive architecture and vibrant culture of cities like Tangier and Fez.

Each new location provided fresh inspiration for his brush. His watercolours of Venice, for example, skillfully depict the city's unique interplay of water, light, and architecture, echoing the traditions of artists like Samuel Prout and James Holland, yet with his own distinct touch. His Moroccan scenes, like those of Egypt, contributed to the Victorian fascination with North African subjects, a field also explored by artists such as Frank Dillon.

Throughout his career, Goodall was an active participant in the London art world. He began exhibiting at major venues early on, including the Royal Academy, the British Institution, and the Society of British Artists. He was elected an Associate of the Royal Society of Painters in Water Colours (RWS) in 1856 and became a full Member in 1864, a testament to his standing among his peers. The RWS was the premier institution for watercolourists, and its exhibitions were important showcases for artists like William Henry Hunt, known for his meticulous still lifes and rustic figures, and Myles Birket Foster, celebrated for his idyllic rural scenes. Goodall exhibited regularly at the RWS for many decades.

His work was recognized with accolades, including a silver medal from the Society of Arts for a watercolour of the Lambeth Palace fire as early as 1836, when he was just seventeen. His interactions with prominent figures like J.M.W. Turner, David Roberts, and Clarkson Stanfield (a renowned marine and landscape painter) further indicate his integration within the artistic circles of his time.

Representative Works and Their Characteristics

While it is difficult to single out a few works from such a prolific career, certain pieces and themes are particularly representative of Goodall's talent.

His Guiana watercolours, such as View on the River Essequibo or his detailed botanical studies like The Victoria Regia Water Lily, are notable for their blend of scientific observation and artistic sensitivity. They capture the exoticism of the region without sacrificing accuracy.

His Egyptian scenes, like The Great Sphinx, Pyramids of Gizeh, often convey a sense of monumental scale and timelessness. Interior of the Mosque of Sultan Hassan, Cairo showcases his mastery of architectural perspective and his ability to depict the intricate details of Islamic design, often with figures that animate the space and provide a sense of contemporary life within historic settings.

Watercolours from his European travels, such as The Rialto Bridge, Venice or views of the Alhambra in Spain, demonstrate his consistent ability to capture the unique character and atmosphere of diverse locales. These works are characterized by their clarity, well-balanced compositions, and often a luminous quality of light.

Throughout his oeuvre, a common thread is his commitment to verisimilitude, combined with a refined aesthetic sense. His figures, though often small in scale within his landscapes and architectural views, are typically well-observed and add a human element to the scenes. His palette, while capable of capturing the vibrant colours of the tropics or the rich hues of Oriental textiles, often favoured subtle gradations and harmonious combinations.

Relationships with Contemporaries and Artistic Milieu

Edward Angelo Goodall operated within a vibrant and competitive artistic milieu. His closest artistic connection was undoubtedly with his own family, particularly his father, Edward Goodall, and his brother, Frederick Goodall. While Frederick achieved greater public fame and focused more on large-scale oil paintings, often with dramatic or sentimental themes, Edward Angelo carved out his own distinct niche as a travelling watercolourist.

He was certainly aware of, and likely influenced by, the leading figures in British watercolour painting. The legacy of J.M.W. Turner, who had elevated watercolour to an expressive power rivalling oil painting, loomed large. The detailed architectural and topographical work of Samuel Prout and the picturesque landscapes of David Cox were also part of the artistic landscape.

In the realm of Orientalist art, David Roberts and John Frederick Lewis were key contemporaries. Roberts' grand, lithographed views of Egypt and the Holy Land set a benchmark for topographical accuracy and romantic appeal. Lewis, with his incredibly detailed and luminous depictions of Cairene life, offered a different, more intimate vision of the East. Goodall's work can be seen as occupying a space between these approaches, combining topographical interest with a keen eye for cultural detail.

His role as an artist for the Illustrated London News placed him at the forefront of a new kind of visual journalism, alongside other "special artists" who travelled the globe to document current events. This work required adaptability and a focus on clear, informative imagery.

The Royal Society of Painters in Water Colours provided a crucial network and exhibition venue. Here, he would have interacted with a wide range of watercolour specialists, from the meticulous still-life painter William Henry Hunt to landscape artists like Alfred William Hunt (no direct relation to William Henry, but a notable landscapist influenced by Ruskin) and Thomas Miles Richardson Jr., known for his evocative landscapes of Britain and the continent. The critical writings of John Ruskin, a powerful advocate for truth to nature and the importance of watercolour, also shaped the artistic climate in which Goodall worked.

Exhibitions, Recognition, and Legacy

Edward Angelo Goodall was a consistent exhibitor throughout his long career. He showed works at the Royal Academy from 1838 to 1884, the British Institution, and Suffolk Street. His primary allegiance, however, was to the Royal Society of Painters in Water Colours, where he exhibited hundreds of works from his election as an Associate in 1856 until shortly before his death.

His Guiana drawings were exhibited at the Colonial Office in London, and later in Berlin (where he also produced botanical watercolours for the Berlin Museum) and Paris, highlighting their scientific and ethnographic importance. His Egyptian sketches were shown at Burlington House.

While he may not have achieved the same level of widespread fame as his brother Frederick, or some of the titans of Victorian art, Edward Angelo Goodall was a respected and successful artist in his own right. His works were collected by private individuals and public institutions. The enduring value of his art lies in its dual capacity: as aesthetically pleasing depictions of diverse landscapes and cultures, and as important historical documents. His meticulous records of Guiana's flora and indigenous peoples, his firsthand views of the Crimean War, and his detailed renderings of Egyptian monuments and life provide invaluable insights into the 19th-century world.

Many of his works are now held in public collections, including the Victoria and Albert Museum, the British Museum, the National Portrait Gallery (which holds portraits of him), the Wellcome Collection in London, and various regional galleries in the UK. His contributions to botanical illustration and ethnographic documentation are particularly prized.

Edward Angelo Goodall died in London on April 16, 1908, at the venerable age of 88. He was buried in Highgate Cemetery, a resting place for many notable Victorians. His life spanned a period of immense change, from the height of British colonial expansion and exploration to the dawn of the modern era. Through his art, he provided a unique window onto that world, rendered with skill, dedication, and a quiet, observant eye. His legacy is that of an artist who not only saw the world but also meticulously and beautifully recorded it for posterity.