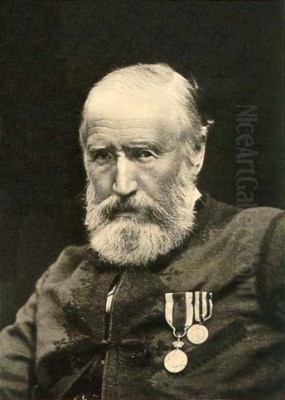

William Simpson stands as a pivotal figure in 19th-century British art, renowned not only for his artistic skill but also for his pioneering role as one of the world's first dedicated war artists. Born in Glasgow, Scotland, on October 28, 1823, his life journey took him from the humble beginnings of a lithographer's apprentice to the battlefields of the Crimea and the far-flung corners of the British Empire and beyond. His prolific output, primarily in watercolour and lithography, provides an invaluable visual record of a transformative era, capturing conflict, culture, and landscapes with remarkable detail and empathy. Simpson's work bridged the gap between direct reportage and fine art, influencing visual journalism and leaving a legacy that continues to inform our understanding of Victorian history and global encounters.

Early Life and Artistic Foundations in Glasgow

William Simpson's early life in Glasgow was marked by hardship. He experienced poverty firsthand, compounded by a difficult family situation with an alcoholic and abusive father. His mother, however, provided a source of kindness and support. His only period of formal schooling occurred during a stay with his grandmother in Perth. Despite these challenging circumstances, his artistic inclinations found an outlet when he was apprenticed to the Glasgow lithographic firm of Macfarlane. Lithography, a relatively new printmaking technique at the time, was becoming increasingly important for commercial illustration and reproduction.

This apprenticeship provided Simpson with a rigorous technical grounding. He honed his skills in drawing directly onto stone, mastering the nuances of tonal variation and precise linework essential for high-quality prints. He later continued his training with another Glasgow firm, Allan & Ferguson. This expertise in lithography would prove foundational to his later career, enabling him to translate his field sketches into widely distributable images for publications and print sellers, long before photographic reproduction became commonplace in newspapers. His Glasgow years instilled in him a strong work ethic and a mastery of graphic representation.

London and the Rise Through Lithography

In 1851, seeking greater opportunities, William Simpson moved to London, the bustling heart of the British Empire and its publishing industry. He secured a position with Day & Son, arguably the most prominent lithographic printing firm in the country at that time. Working at Day & Son placed Simpson at the forefront of print technology and visual culture. The firm was renowned for its high-quality colour lithographs, often used for prestigious publications, including illustrated books and portfolios.

His skills were quickly recognized, and he became a key artist within the company. This period allowed him to refine his craft further and gain exposure to a wider range of subjects and artistic styles. His work for Day & Son demonstrated his versatility and technical prowess, establishing his reputation within the London art and publishing world even before his defining experiences as a war artist. This position provided the crucial stepping stone towards the commission that would catapult him to international fame.

The Crimean War: Forging a Reputation

The outbreak of the Crimean War (1853-1856) presented a unique opportunity. Public interest in the conflict was immense, fueled by patriotic fervor but also growing concern about the war's management, reported vividly by correspondents like William Howard Russell of The Times. The Illustrated London News (ILN), a hugely popular publication that pioneered the use of wood engravings to depict current events, sought artists to provide visuals from the front. While photography, practiced in Crimea by figures like Roger Fenton and James Robertson, was emerging, its technical limitations made it slow and unsuitable for capturing action. Drawings remained essential.

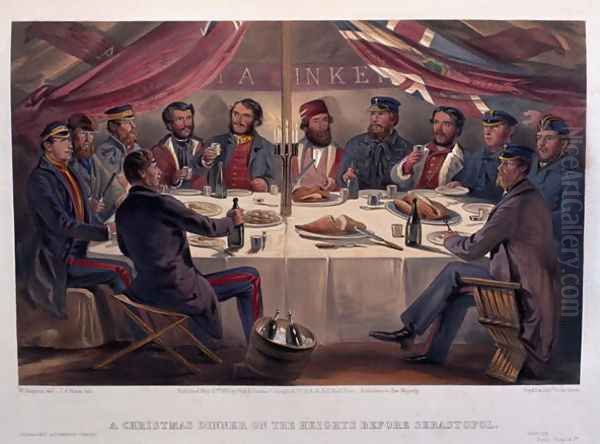

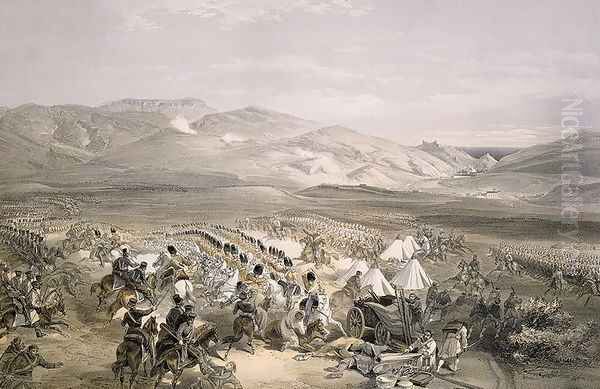

Initially, the publishers P&D Colnaghi & Co. commissioned Simpson to create sketches based on descriptions and drawings by officers returning from the front. However, recognizing the need for firsthand accounts, Colnaghi decided to send Simpson directly to the Crimea in 1854. He arrived shortly after the Battle of Inkerman and spent over a year documenting the harsh realities of the campaign: the battles, the sieges (particularly of Sevastopol), the conditions in the camps, and the landscapes of the conflict zone.

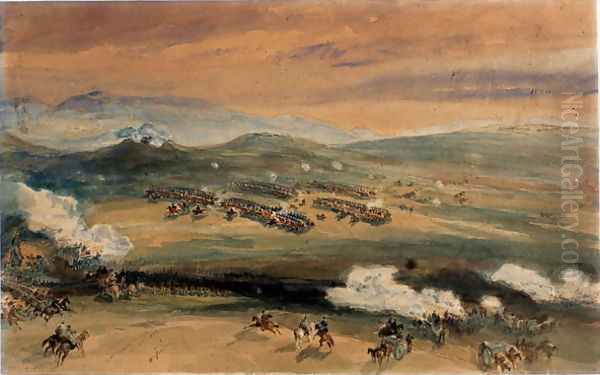

Simpson worked tirelessly, often under dangerous conditions, producing hundreds of sketches. These were sent back to London, where they were translated into lithographs by Day & Son for Colnaghi's publication and also used as the basis for wood engravings in the Illustrated London News. His detailed and dramatic watercolours captured the public imagination, offering a more immediate and often grittier view of the war than the often-stilted official accounts or posed photographs.

His work was noted for its accuracy and attention to detail, providing valuable insights into military life, technology, and the human cost of the war. He didn't shy away from depicting the hardships and logistical failures that plagued the campaign. This commitment to visual truth earned him immense respect and the enduring nickname "Crimean Simpson." His efforts significantly shaped public perception of the war in Britain.

The Seat of War in the East

The culmination of Simpson's Crimean work was the monumental publication The Seat of War in the East, published by Colnaghi in two series between 1855 and 1856. Comprising 81 tinted lithographs produced by Day & Son based on Simpson's original watercolours, this portfolio was a landmark achievement in war reportage and printmaking. The prints covered all major aspects of the campaign, from grand battle panoramas and depictions of key fortifications to intimate scenes of camp life and portraits of military figures.

The series was a critical and commercial success. Queen Victoria herself became an admirer of Simpson's work, summoning him to show his sketches and purchasing copies of the portfolio. This royal patronage significantly boosted his reputation. The Seat of War in the East set a new standard for illustrated war reporting, demonstrating the power of the artist-correspondent to convey the atmosphere and reality of conflict to a distant public. It remains one of the most important visual documents of the Crimean War and a testament to Simpson's skill and bravery. The success of this publication solidified his career and opened doors for future assignments across the globe.

Expanding Horizons: India

Following his Crimean success, Simpson's thirst for travel and documentation grew. In 1859, he embarked on a major journey to India, initially commissioned to depict scenes related to the aftermath of the Indian Mutiny (also known as the Sepoy Rebellion or First War of Independence) of 1857. This conflict had deeply shaken the British establishment, and there was intense interest in the subcontinent. Simpson spent nearly three years travelling extensively across India, from the Himalayas in the north to Ceylon (modern Sri Lanka) in the south.

His focus extended far beyond the immediate aftermath of the Mutiny. He became deeply fascinated by India's rich history, diverse cultures, stunning architecture, and religious practices. He sketched temples, mosques, palaces, landscapes, and scenes of daily life with meticulous care. His training as a lithographer gave him an eye for architectural detail, while his growing skill with watercolour allowed him to capture the vibrant colours and atmosphere of the country. He documented archaeological sites, providing valuable records of monuments, some of which have since changed or deteriorated.

During his time in India, he produced a vast portfolio of sketches and watercolours. These formed the basis for a planned, lavishly illustrated book titled India Ancient and Modern. Although the full project ultimately proved too expensive to publish in its intended form, many of the images were later reproduced in other publications or exhibited. Some of the original watercolours, such as the depiction of the magnificent Kailasanath Temple at Ellora, are now held in major collections like the British Museum. His Indian work showcases a shift towards a more ethnographic and archaeological focus, alongside his topographical skills. His experiences also deepened his interest in comparative religion, particularly Hinduism and Buddhism. He even had another audience with Queen Victoria upon his return to show his Indian sketches.

Journeys Further East: China, Tibet, and Beyond

Simpson's wanderlust was far from quenched. The Illustrated London News, recognizing his talent and reliability, employed him as a 'special artist' for decades, sending him to cover significant events worldwide. In 1866, he accompanied an expedition to Russia to sketch the marriage of the Tsarevitch (later Tsar Alexander III). Two years later, he was in Abyssinia (modern Ethiopia) covering the British expedition led by Sir Robert Napier.

A particularly significant journey occurred in 1872-73 when he accompanied the Prince of Wales (later King Edward VII) on a tour that included China. This provided him access to places and events not easily reachable by ordinary travellers. He documented the landscapes, cities like Peking (Beijing), and ceremonial occasions. His sketches of the Great Wall of China captured its monumental scale and rugged setting. This trip further exposed him to East Asian cultures and art forms.

His travels also took him to regions then considered remote and exotic by Europeans, including Tibet and Nepal, although his access might have been limited to border areas or specific routes. He continued to document architecture, religious sites (like Buddhist monasteries), and local customs. These journeys cemented his reputation as not just a war artist but a comprehensive visual chronicler of the wider world during a period of intense global exploration and colonial expansion. His work provided British audiences with glimpses into cultures vastly different from their own, filtered through his skilled and observant eye.

Archaeology, Ethnography, and the Holy Land

Simpson's travels fostered a deep and abiding interest in archaeology and ethnography. He wasn't merely sketching picturesque views; he was actively engaged in understanding the history and significance of the places he visited. He attended archaeological digs and documented findings, sometimes producing illustrations for archaeological reports. His meticulous drawings of ancient sites, inscriptions, and artifacts were valued by scholars.

In 1869, he travelled to the Middle East, spending considerable time in Jerusalem. This visit coincided with significant archaeological work being undertaken by the Palestine Exploration Fund, particularly the excavations around the Temple Mount led by Charles Warren. Simpson documented these explorations, producing works like Underground Jerusalem, which depicted the subterranean tunnels and structures being revealed. His interest went beyond the purely topographical; he was fascinated by the religious history and symbolism embedded in the landscape and architecture of the Holy Land.

His ethnographic interests are evident in his detailed depictions of people, their clothing, customs, and religious practices across the many cultures he encountered. He approached these subjects with curiosity and a degree of empathy unusual for the era. This interest culminated in several publications where he explored comparative religion and symbolism, such as his work on the Swastika symbol and the aforementioned The Buddhist Praying-Wheel (1896). While some of his theories might be viewed critically today, they reflect a genuine attempt to understand non-European belief systems.

Later Travels and Conflicts

Simpson's career as a special artist for the Illustrated London News continued into his later years. He covered the Franco-Prussian War in 1870, witnessing the Siege of Paris. His experience in warfare made him a valuable asset for depicting these contemporary conflicts. He was present at the opening of the Suez Canal in 1869, a major geopolitical event.

One of his last major assignments was to Afghanistan during the Second Anglo-Afghan War (1878-1880). He accompanied the British forces, sketching the challenging terrain, military engagements, and interactions with local peoples. This journey, undertaken when he was in his late fifties, demonstrated his enduring stamina and commitment to his profession. The Afghan landscapes and campaign scenes added another chapter to his extensive visual record of Victorian military engagements.

These later assignments reinforced his reputation as Britain's foremost graphic correspondent. His ability to quickly capture the essence of a scene and convey it effectively for reproduction in the ILN was unparalleled. He worked alongside other ILN artists over the years, such as Melton Prior and Frank Vizetelly, who also covered numerous conflicts, but Simpson's breadth of experience and early fame gave him a unique status. His work consistently provided the British public with visual access to the frontiers of empire and the theatres of European conflict.

Artistic Style and Technique

William Simpson's artistic style evolved throughout his long career, yet certain characteristics remained constant. His foundation in lithography instilled a strong sense of line and tonal control. His early work, including the Crimean lithographs, is marked by clarity, detail, and a focus on accurate representation. He excelled at rendering complex scenes, whether battlefields crowded with soldiers or intricate architectural facades.

As he increasingly worked in watercolour during his travels, his style gained fluency and expressiveness. While maintaining topographical accuracy, his Indian and later works often show a greater sensitivity to light, colour, and atmosphere. He developed a remarkable ability to capture the specific quality of light in different climates, from the haze of the Indian plains to the clear air of the Himalayas. His compositions remained carefully constructed, often employing dramatic perspectives or focusing on telling details to convey the narrative or mood of a scene.

Compared to the high romanticism of artists like J.M.W. Turner, Simpson's work was generally more descriptive and reportorial. Yet, it was not devoid of artistic sensibility. He had a talent for creating visually engaging images that were both informative and aesthetically pleasing. His primary medium for fieldwork was watercolour over pencil sketches, often annotated with notes. These field studies possess an immediacy and freshness that is sometimes lost in the final lithographs or wood engravings produced back in London, though the prints made his work accessible to a vast audience. His dedication to on-the-spot sketching links him to a tradition of British topographical watercolourists like David Roberts, but his role as a press artist gave his work a unique urgency and context.

Simpson the Writer and Ethnographer

Beyond his visual art, William Simpson was also a prolific writer. His extensive travels and observations provided rich material for articles and books. His autobiography, published posthumously in 1903 and edited by George Eyre-Todd, offers invaluable insights into his life, working methods, and the historical events he witnessed. It remains a key source for understanding his career and the world of 19th-century journalism and exploration.

His fascination with comparative religion and symbolism led to several scholarly, if sometimes speculative, publications. The Buddhist Praying-Wheel (1896) explored the origins and symbolism of this ritual object across different cultures. He also wrote extensively on topics such as the origin of the Swastika symbol (which had not yet acquired its toxic 20th-century associations), serpent worship, and aspects of Christian symbolism. These writings demonstrate the intellectual curiosity that underpinned his artistic practice. He saw himself not just as an illustrator but as an investigator of human culture and history.

An anecdote mentioned in the provided text highlights his unconventional engagement with other cultures: apparently, he once joined a Hindu monk (sadhu) in selling paintings on the streets of Paris. While perhaps apocryphal or embellished, such a story reflects his known interest in Eastern philosophies and his somewhat bohemian willingness to cross cultural boundaries, setting him apart from more conventional Victorian gentlemen-travellers. His writings and his art together reveal a man deeply engaged with the diversity of the world he documented.

Collaborations and Contemporaries

Simpson's career was deeply intertwined with the publishing and art world of his time. His long association with the Illustrated London News meant he was part of a team of artists providing visuals for the paper. While direct collaborations on single images might have been rare for 'special artists' working abroad, his work appeared alongside that of other prominent illustrators like Constantin Guys (who also covered Crimea briefly), Melton Prior, Frank Vizetelly, and later artists who followed in the tradition of the 'special'. The ILN itself was a collaborative enterprise, involving sketch artists, engravers, writers, and editors.

His work for publishers P&D Colnaghi and printers Day & Son on The Seat of War in the East was a major collaborative project, involving the translation of his watercolours into high-quality lithographs by skilled artisans at Day & Son. In the context of the Crimean War, his drawings complemented the pioneering, though static, photographic work of Roger Fenton and James Robertson.

In India, his documentation of architecture and landscapes invites comparison with earlier artists like Thomas Daniell and William Daniell, whose aquatints shaped British perceptions of India, and contemporaries or near-contemporaries like the travelling artist Edward Lear, who also visited India, though with a different artistic focus. Simpson's work also paralleled the efforts of early photographers in India, such as Samuel Bourne and Lala Deen Dayal, who were also documenting the country's monuments and people.

Within the broader Victorian art scene, Simpson occupied a distinct niche. He was not a Royal Academician focused on large oil paintings like many contemporaries, nor aligned with movements like the Pre-Raphaelites. His focus on reportage and watercolour places him closer to the tradition of topographical artists like David Roberts (famous for his Near Eastern views) but updated for the age of mass media. His commitment to observed detail aligns with the principles advocated by the influential critic John Ruskin, though Simpson's subjects were often more journalistic than the natural landscapes Ruskin typically championed. He also worked in an era where dramatic illustration, exemplified by figures like Gustave Doré in France, was highly popular, and Simpson's own work often contained dramatic elements suited to popular taste.

Legacy and Collections

William Simpson died in Willesden, London, on August 17, 1899. He left behind an immense body of work that serves as a crucial visual archive of the Victorian era. His contributions as a war artist were foundational, establishing a model for graphic reportage that persisted until photography could fully take over the role in the 20th century. His detailed observations provide historians with invaluable information about military campaigns, technology, uniforms, and the conditions faced by soldiers.

His travel watercolours and sketches are equally significant, offering a panoramic view of the world during a period of intense global change and interaction. They document architecture, archaeological sites, cultural practices, and landscapes across Europe, Africa, and Asia. His work reflects both the imperial context of his time and his own genuine curiosity about other cultures.

Major institutions hold significant collections of Simpson's work. The Victoria and Albert Museum (V&A) in London houses a large number of his watercolours and sketches, particularly from his travels. The British Museum holds important works, including watercolours intended for India Ancient and Modern. The Mitchell Library (part of Glasgow Libraries) in his native city also holds relevant material, reflecting his Scottish origins. His works continue to appear at auction, with pieces like his Crimean watercolours and lithographs from The Seat of War in the East commanding collector interest, indicating the enduring appreciation for his artistic skill and historical significance. For example, works from The Seat of War were estimated at £1000-£1500 in 2015, while individual watercolours like Bombardment of Sebastopol have reached estimates of £1500-£2000, reflecting their market value.

Conclusion: Chronicler of an Empire

William Simpson's life spanned a period of dramatic transformation, and his art provides a unique window onto that world. From the smoke-filled battlefields of the Crimea to the ancient temples of India and the bustling cities of China, he documented his era with unparalleled dedication and skill. As one of the very first 'special artists', he pioneered the field of visual journalism, bringing distant events and foreign lands vividly to life for the British public through publications like the Illustrated London News.

His technical mastery, honed through years as a lithographer, combined with his keen eye for detail and his adventurous spirit, made him the ideal chronicler for an age of exploration, conflict, and empire. While inevitably viewed through a Victorian lens, his work often displays a remarkable degree of accuracy and empathy. More than just an illustrator, Simpson was an observer, an ethnographer, an amateur archaeologist, and a tireless traveller. His legacy resides not only in the aesthetic quality of his watercolours and prints but also in the rich historical and cultural record they constitute, preserving moments in time from across the 19th-century globe.