Introduction: A Victorian Visionary

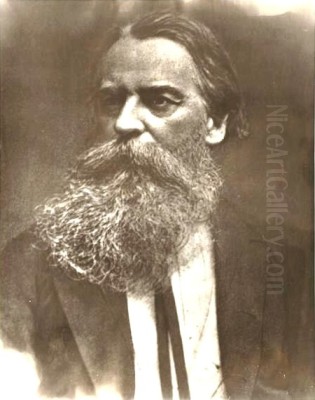

Thomas Baines (1820-1875) stands as a remarkable figure of the Victorian era, a man whose life and work encapsulate the period's fervent spirit of exploration, scientific inquiry, and colonial expansion. More than just an artist, Baines was an intrepid explorer, a keen naturalist, a cartographer, and a diarist. His extensive travels across Southern Africa and Australia provided him with a vast canvas, both literally and figuratively, upon which he documented the landscapes, flora, fauna, and peoples he encountered with a distinctive blend of scientific precision and Romantic sensibility. His legacy is complex, reflecting both the artistic achievements of a dedicated observer and the often problematic colonial ideologies of his time. This article will delve into the multifaceted life and career of Thomas Baines, examining his journeys, his artistic development, his significant works, his relationship with contemporaries, and the enduring, sometimes controversial, impact of his contributions to art and history.

Early Life and Artistic Awakening

John Thomas Baines was born on November 27, 1820, in King's Lynn, Norfolk, England. His father was a master mariner, and it's possible that tales of the sea and distant lands sparked an early interest in adventure in the young Baines. His formal education was modest, but he was apprenticed at the age of 16 to an ornamental painter, William Carr, where he learned the foundational skills of coach painting. This trade, while seemingly humble, would have instilled in him a practical knowledge of pigments, oils, and application techniques, as well as the discipline of detailed work, which would prove invaluable in his later artistic endeavors.

During his apprenticeship, Baines developed a passion for drawing and painting, particularly marine subjects and landscapes, inspired by the bustling port life of King's Lynn. He was largely self-taught as an artist in the finer sense, honing his skills through observation and practice. Even at this early stage, a meticulous attention to detail and a desire to capture the world around him accurately were evident. This period laid the groundwork for his later ability to work quickly and effectively in often challenging field conditions, producing sketches and paintings that were both informative and aesthetically engaging. His early exposure to the practicalities of a trade, combined with his innate artistic talent, shaped him into a versatile and resourceful individual, well-suited for the demanding life of an expeditionary artist.

The Call of Africa: First Sojourn and the Cape Frontier Wars

In 1842, at the age of 21, Thomas Baines made a pivotal decision that would define the course of his life: he emigrated to the Cape Colony in Southern Africa. Arriving in Cape Town, he initially sought to establish himself as a portrait and marine painter. The vibrant colonial port, with its dramatic backdrop of Table Mountain, offered ample subject matter. During this period, he would have been aware of the work of other artists active in the Cape, such as Thomas William Bowler, known for his detailed watercolors and prints of Cape Town and its surroundings, and Frederick Timpson I'Ons, who was documenting life, including military engagements, on the Eastern Frontier.

Baines's adventurous spirit soon drew him away from the relative comfort of Cape Town. He embarked on several journeys into the interior of the Cape Colony. His skills as an artist were increasingly in demand for documenting these less-charted territories. Between 1848 and 1851, his path led him to the Eastern Cape, where he served as an official war artist during the 7th and 8th Cape Frontier Wars (often referred to at the time, and in some of the provided information, as the "Kaffir Wars" – a term now considered offensive but reflecting the colonial lexicon of the era). Attached to the British forces, Baines witnessed and recorded numerous skirmishes and military operations.

His works from this period, such as General Somerset's Division on the March (1854, though depicting earlier events), provide valuable, if partisan, visual records of these conflicts. They often showcase the British military in a heroic light, navigating rugged terrain and engaging with Xhosa warriors. These paintings and sketches demonstrate his developing ability to capture dramatic action and expansive landscapes, often imbued with a sense of imperial confidence. This experience solidified his reputation as an artist capable of working under duress and providing visual intelligence, a role highly valued in an era of colonial expansion. His depictions, while serving an imperial narrative, also offer glimpses into the topography and the nature of frontier warfare, making them important historical documents. The earlier work of Samuel Daniell, who had documented the peoples and wildlife of Southern Africa at the beginning of the 19th century, might have provided a precedent for Baines in terms of expeditionary art.

Australian Interlude: Documenting a New Frontier

Following his experiences in Southern Africa, Baines's thirst for exploration led him further afield. In 1855, he joined Augustus Charles Gregory's North Australian Expedition, sponsored by the Royal Geographical Society, of which Baines had become a fellow in 1842. This ambitious expedition aimed to explore the Victoria River district and assess the region's potential for pastoralism and settlement. Baines served as the official artist and storekeeper for the expedition, which lasted until 1857.

During this arduous journey, Baines meticulously documented the unfamiliar landscapes, the unique flora and fauna of Northern Australia, and the encounters with Indigenous Australian communities. His works from this period, such as A Bend of the Victoria River, North Australia, showcase his skill in capturing the vastness and distinctive character of the Australian outback. He produced a wealth of sketches, watercolors, and oil paintings, many of which were later used to illustrate expedition reports and popular accounts of the journey. His depictions of Aboriginal life, while filtered through a European lens, are valuable for their observational detail.

The Australian environment presented new challenges and inspirations. The quality of light, the colors of the earth, and the forms of the vegetation were distinct from those he had encountered in Africa. Baines adapted his palette and techniques accordingly. His work in Australia can be seen in the context of other colonial artists working on the continent, such as Conrad Martens, who had earlier accompanied Charles Darwin on the Beagle and was known for his Romantic landscapes, and Eugene von Guérard, celebrated for his detailed and majestic depictions of the Australian wilderness. S.T. Gill was another contemporary, known for his lively sketches of colonial life and the goldfields. Baines's contribution was unique in its focus on the remote northern territories, providing some of the earliest European artistic impressions of this region.

The Zambezi Expedition: Triumph and Tribulation

Upon his return to England, Baines's reputation as an experienced expeditionary artist was firmly established. This led to his appointment in 1858 as artist and storekeeper to David Livingstone's Zambezi Expedition. This was a high-profile undertaking, aimed at exploring the navigability of the Zambezi River, assessing its economic potential, and promoting legitimate commerce as an alternative to the slave trade. Other members included the botanist Dr. John Kirk.

Baines diligently recorded the expedition's progress, producing a remarkable series of artworks depicting the river, its landscapes, and its wildlife, including the famed Victoria Falls (Mosi-oa-Tunya). His painting Devil’s Cataract, Victoria Falls (1862) is a powerful example, conveying the immense power and sublime beauty of the falls. He employed an expanded color range and heightened tonality to capture his emotional response to the scene, moving beyond mere topographical accuracy to evoke a sense of awe. This approach reflects the Romantic sensibilities prevalent in 19th-century landscape painting, where artists like J.M.W. Turner in Britain sought to capture the elemental forces of nature.

However, the Zambezi Expedition was fraught with difficulties, including disease, challenging terrain, and interpersonal tensions. In 1859, Baines was controversially dismissed by David Livingstone amidst accusations of theft (specifically, of expedition sugar and canvas, which Baines maintained he used for painting with permission or out of necessity). Baines vehemently denied these charges, and many historians now believe he was unfairly treated, possibly a scapegoat for some of the expedition's broader failings or a victim of personality clashes. The dismissal was a significant blow to Baines's career and reputation at the time, though he continued to defend his name. Despite this unfortunate end, his artistic output from the Zambezi Expedition remains a vital record of this important chapter in African exploration.

Later African Explorations and Artistic Maturity

Undeterred by the Zambezi debacle, Thomas Baines continued his exploratory and artistic work in Southern Africa. From 1861 to 1864, he undertook significant journeys in South-West Africa (present-day Namibia) and Bechuanaland (present-day Botswana) with fellow explorer James Chapman. Their aim was to explore a route from Walvis Bay to Victoria Falls. During these travels, Baines produced a wealth of material, including detailed maps and numerous paintings. His book, Explorations in South-West Africa (1864), chronicled these adventures.

One of his most scientifically important and artistically striking works from this period is Welwitschia mirabilis in situ, in the Hyæna Vley, Damaraland (1867, based on sketches from 1861). This painting meticulously depicts the extraordinary desert plant, Welwitschia mirabilis, in its natural habitat, complete with figures of explorers (including Baines himself) examining it. The artwork beautifully marries scientific accuracy with a sense of discovery and the harsh beauty of the Namib Desert. It exemplifies his ability to function as both a naturalist and an artist, a trait shared with earlier naturalist-artists like François Le Vaillant, whose travels and illustrated accounts of Southern Africa in the late 18th century had captivated Europe.

In the later 1860s and early 1870s, Baines was involved in expeditions to the goldfields of Mashonaland (in present-day Zimbabwe). He secured a concession from Lobengula, king of the Ndebele, to prospect for gold. His paintings from this period document the landscapes, the mining activities, and his interactions with local leaders and peoples. Works like Zulus Dancing beneath a Fig Tree capture ethnographic details, though always within the framework of the colonial encounter. His painting Durban from Mr. Currie's Residence (1873) shows a developing colonial port, reflecting the Victorian era's preoccupation with progress and the transformation of landscapes.

Artistic Style and Thematic Concerns

Thomas Baines's artistic style is a fascinating amalgamation of the prevailing artistic and scientific currents of the 19th century. His work is characterized by a commitment to topographical accuracy and detailed observation, reflecting the scientific empiricism of the era. Yet, it is often infused with a Romantic sensibility, evident in his dramatic compositions, his attention to atmospheric effects, and his ability to convey the sublime grandeur of the natural world.

Romanticism and Scientific Observation: Baines navigated the complex relationship between objective reality and subjective expression. While his training and role as an expeditionary artist demanded a high degree of accuracy in depicting landscapes, geological formations, flora, and fauna, his compositions often transcended mere illustration. He employed panoramic perspectives, as seen in South-West Corner of Lake Ngami (1864), which depicts storm clouds gathering over the lake, evoking a sense of nature's power and the vastness of the African interior. This dual approach – the scientist's eye for detail and the artist's soul for beauty and drama – is a hallmark of his best work. His botanical illustrations, for instance, are precise enough for scientific identification but are also aesthetically pleasing compositions.

The Colonial Gaze: It is impossible to separate Baines's work from the colonial context in which it was created. His expeditions were often intertwined with the agendas of imperial expansion, resource assessment, and the "civilizing mission." His art, consciously or unconsciously, often served these agendas. Landscapes were depicted as territories to be explored, mapped, and potentially exploited. Indigenous peoples were frequently portrayed as exotic "others," or as part of the natural landscape, sometimes in ways that reinforced notions of European cultural superiority. While he often showed a genuine interest in and respect for local cultures, his perspective was inevitably that of a European man of his time. This "colonial gaze" is a critical aspect of understanding his work today and is a theme explored in the work of later South African artists like Jacob Hendrik Pierneef, whose stylized landscapes, while different, also engaged with themes of land and belonging, albeit from a later Afrikaner nationalist perspective. The idea of landscape painting asserting control or sovereignty, as seen in Baines's work, has parallels in the work of other artists depicting newly claimed territories, perhaps even some European landscape traditions where artists like Claude Lorrain structured idealised landscapes.

Versatility in Media: Baines was proficient in a variety of media. He produced rapid pencil and watercolor sketches in the field, which often formed the basis for more finished oil paintings completed later in his studio or back in England. He was also a skilled cartographer, and his maps were valuable contributions to the geographical knowledge of the regions he explored. His journals and published accounts were often illustrated with wood engravings based on his drawings, making his discoveries accessible to a wider public. This versatility allowed him to adapt to different needs and conditions, from quick field notes to elaborate exhibition pieces.

Notable Works: A Closer Look

Several of Baines's works stand out for their artistic merit, historical significance, or scientific importance:

Devil’s Cataract, Victoria Falls (1862): This oil painting captures the raw power and misty grandeur of one section of the Victoria Falls. Baines uses dynamic brushwork and a dramatic play of light and shadow to convey the immense volume of water and the spray rising into the air. The inclusion of small human figures emphasizes the scale and overwhelming force of nature, a common trope in Romantic landscape painting.

South-West Corner of Lake Ngami, with storm-clouds gathering (1864): This panoramic landscape demonstrates Baines's skill in capturing atmospheric effects. The vast, flat expanse of the lake and surrounding land is overshadowed by dramatic, dark storm clouds, creating a sense of impending drama and the untamed wilderness. It reflects both the sublime beauty and the potential dangers of the African interior.

General Somerset's Division on the March, Amatola Mountains in the Distance (1854): This work, stemming from his time as a war artist, depicts a column of British troops and wagons traversing a rugged landscape. It is a detailed portrayal of military logistics and colonial power projection during the Cape Frontier Wars. The composition emphasizes the organized might of the imperial forces against the backdrop of a vast and challenging terrain.

Durban from Mr. Currie's Residence, Natal (1873): This painting offers a view of the burgeoning colonial port of Durban. It shows the development of the town, with buildings, cultivated land, and ships in the harbor. It reflects the Victorian ideal of progress and the transformation of the African landscape through European settlement and commerce.

Welwitschia mirabilis in situ, in the Hyæna Vley, Damaraland (1867): As mentioned earlier, this is a key work combining botanical accuracy with a narrative of scientific discovery. The strange, ancient plant is the clear focus, rendered with meticulous detail, while the figures of Baines and his companions provide scale and context, highlighting the human endeavor of exploration and scientific documentation.

Langalibalele Rebellion Sketch (1873, unpublished): This sketch, depicting a conflict scene at Bushman's River Pass during the Langalibalele Rebellion, is significant for what it reveals about potential self-censorship or external pressures on Baines as an "imperialist artist." The existence of differing versions or the suppression of certain details in official accounts points to the complexities of representing colonial conflict.

Baines and His Contemporaries: A Network of Influence

While Baines often worked in remote locations, he was part of a broader network of artists, explorers, and scientists. His membership in the Royal Geographical Society connected him with leading figures in British exploration.

In Southern Africa, his early contemporaries included Thomas William Bowler, whose picturesque views of Cape Town and its environs were popular, and Frederick Timpson I'Ons, who, like Baines, documented the Eastern Frontier. Charles Davidson Bell, Surveyor-General of the Cape and a versatile artist, also produced important visual records of expeditions and local life. Later, artists like Abraham de Smidt, a contemporary of Baines, also focused on South African landscapes, though often with a more settled, pastoral feel.

During his Australian expedition, Baines's work can be compared to that of Conrad Martens and Eugene von Guérard, who were instrumental in shaping the European vision of the Australian landscape, often emphasizing its grandeur and unique features. S.T. Gill provided a more anecdotal, everyday view of colonial life.

In the wider context of 19th-century expeditionary art, Baines shares kinship with artists who accompanied voyages of discovery globally. The tradition of artists on scientific expeditions was well-established, with figures like Sydney Parkinson (Captain Cook's first voyage) and William Hodges (Cook's second voyage) setting early precedents. Baines's meticulous recording of flora and fauna also aligns him with the great tradition of natural history illustrators, such as John James Audubon in America or John Gould in Britain and Australia, though Baines's scope was broader.

His relationship with David Livingstone is, of course, central to one phase of his career. While their collaboration ended acrimoniously, their initial shared purpose on the Zambezi Expedition highlights the interconnectedness of exploration, science, and art. Dr. John Kirk, the botanist on the same expedition, also produced photographs, representing an emerging technology for documentation.

The provided information also mentions stylistic similarities in expressing control and sovereignty with J.H. Pierneef, Jan Ernst van der Burg, and Pierre Vercollon. Pierneef is a major figure in South African art, whose later work indeed explores themes of land and identity. Van der Burg and Vercollon are less widely known in broader art historical narratives but may represent specific regional or thematic comparisons relevant to Baines's depiction of territory.

The Colonial Lens: Controversy and Context

A critical assessment of Thomas Baines's work necessitates an understanding of its colonial context. He was an agent of empire, whether consciously or not. His art often served to map, document, and, in a sense, visually possess territories for the British Empire. His depictions of indigenous peoples, while often detailed and sometimes sympathetic, were framed by the prevailing racial hierarchies and colonial attitudes of the Victorian era. They were frequently presented as elements of an exotic landscape or as subjects of ethnographic study, rather than as individuals with their own complex societies and agencies.

The idea that his works were "educational" but also "embodied the colonial ideal of European cultural superiority" is a crucial point. His art helped to familiarize the British public with distant lands and peoples, but this familiarization often reinforced imperial narratives of adventure, discovery, and the perceived benefits of colonial rule. The "truthfulness" in his art, as noted in some analyses, could be interpreted as a visual rhetoric supporting the legitimacy of territorial claims and colonial governance.

The controversy surrounding his sketch of the Langalibalele Rebellion (1873) is a case in point. The suggestion that he may have been "forced into artistic censorship" highlights the pressures faced by artists working within the imperial framework. Depicting colonial conflicts in a way that was too graphic or that questioned the actions of colonial forces could be problematic for an artist reliant on patronage and official support. This incident underscores the complex interplay between artistic representation, political power, and historical memory.

Modern art historical scholarship, particularly from postcolonial perspectives, has critically re-examined the work of artists like Baines. While acknowledging their skill and the historical value of their documentation, these perspectives also highlight the power dynamics inherent in the colonial encounter and the ways in which art participated in the construction of imperial ideologies.

Legacy and Re-evaluation

Thomas Baines died in Durban, Natal, on May 8, 1875, at the age of 54, reportedly from dysentery contracted during his travels. He left behind an enormous body of work – thousands of paintings, sketches, maps, and detailed journals.

For many years, Baines was perhaps more celebrated as an explorer and diarist than as a fine artist. He was sometimes categorized primarily as an "illustrator," a label that, while acknowledging his documentary function, could also subtly diminish his artistic achievements. However, there has been a growing recognition of his artistic skill, his unique vision, and the rich historical and cultural information embedded in his work.

His paintings are now held in numerous collections in South Africa, the United Kingdom, Australia, and elsewhere. They are invaluable resources for historians, geographers, botanists, and anthropologists, providing visual data on landscapes that have since changed, wildlife, and cultural practices. The Royal Geographical Society in London holds a significant collection of his work, a testament to his contributions to exploration.

The re-evaluation of Baines's work in recent decades has also involved a more critical engagement with its colonial dimensions. While his art provides a window into the 19th-century world, it is a window framed by the perspectives and prejudices of his time. Understanding this context does not negate the value of his work but allows for a more nuanced appreciation of its complexities. He remains a key figure in the study of colonial art and the history of European engagement with Africa and Australia. His influence on subsequent South African art may be indirect, but his role in establishing a tradition of landscape painting and documentary art in the region is undeniable.

Conclusion: An Enduring Chronicle

Thomas Baines was a man of extraordinary energy, talent, and resilience. His life was one of constant movement, observation, and creation. He navigated the challenges of arduous expeditions, political intrigues, and personal setbacks, all while producing a prolific and diverse body of artistic and written work. His paintings and drawings offer an unparalleled visual record of the regions he explored, capturing moments of discovery, encounters with diverse cultures, and the transformative impact of colonial expansion.

While his work is inextricably linked to the imperial project of the 19th century, and must be viewed through that critical lens, its value extends beyond its colonial origins. Baines's meticulous attention to detail, his ability to convey the character of a landscape, and his moments of genuine artistic insight ensure his enduring importance. He was a chronicler of worlds in transition, and his art continues to speak to us today, offering rich material for understanding not only the history of exploration and empire but also the enduring human impulse to observe, record, and interpret the world around us. His legacy is a testament to a life lived at the intersection of art, science, and adventure, leaving an indelible mark on the visual and historical record of the 19th century.