Edward Lamson Henry, often known as E.L. Henry, stands as a significant figure in American art history. Born in Charleston, South Carolina, in 1841, he passed away in Ellenville, New York, in 1919. An American painter of considerable renown, Henry dedicated much of his career to capturing the essence of American life, particularly focusing on colonial times, the early republic, and the rural landscapes and activities of the 19th century. His work provides a detailed and often nostalgic window into a bygone era, rendered with meticulous attention to detail and a strong commitment to historical accuracy. His primary period of artistic activity spanned from the mid-19th century until his death in the early 20th century.

Early Life and Artistic Formation

Though born in the South, Henry's formative years and professional life were largely centered in the North, particularly New York City, where he eventually settled and established his studio. His artistic inclinations emerged early, leading him to pursue formal training. He began his studies at the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts (PAFA) in Philadelphia, one of America's oldest and most prestigious art institutions. During his time there, he studied under instructors like Walter M. Opper, absorbing the foundational principles of drawing and painting.

Seeking to broaden his artistic horizons, Henry, like many ambitious American artists of his generation, traveled to Europe in 1860. He settled in Paris, the epicenter of the art world at the time. There, he immersed himself in further study, working under the guidance of prominent artists Charles Gleyre and Gustave Courbet. Gleyre, known for his academic precision and classical themes, and Courbet, a leading figure of the Realist movement known for his unvarnished depictions of contemporary life, offered Henry exposure to differing but influential artistic philosophies. This European experience undoubtedly refined his technique and shaped his commitment to realism.

The Civil War and its Influence

Henry's artistic development was briefly interrupted by the American Civil War. In 1864, he served the Union cause, not as a combat soldier, but as a captain's clerk aboard transport and supply vessels. This role placed him in a unique position to observe the logistics and atmosphere of the war effort firsthand. During his service, he continued to sketch, capturing scenes related to military life and the landscapes affected by the conflict.

While not primarily known as a painter of battle scenes in the same vein as some contemporaries, this wartime experience provided Henry with invaluable insights and subject matter. It deepened his connection to American history and likely reinforced his interest in documenting pivotal moments and everyday life during significant periods of national transformation. The sketches and memories from this time informed his understanding of the era he so often depicted.

Establishing a Career in New York

Following the conclusion of the Civil War, Edward Lamson Henry returned to New York City, ready to establish himself as a professional artist. In 1868, he took a significant step by opening a studio in the famed Tenth Street Studio Building. This building was a vital hub for the New York art world, housing the studios of many prominent artists of the day, including figures like Albert Bierstadt, Frederic Edwin Church, and Winslow Homer. Working in such proximity to other leading painters provided opportunities for interaction, critique, and participation in the city's vibrant artistic community.

Henry's talent and dedication quickly gained recognition. He became actively involved with the National Academy of Design (NAD), a central institution for American artists. He was elected an Associate Member (ANA) and subsequently achieved the status of full Academician (NA) in 1869. Membership in the NAD was a mark of professional achievement and allowed him to exhibit his work regularly, further solidifying his reputation among peers, critics, and collectors.

Artistic Style and Genre

Edward Lamson Henry's artistic style is firmly rooted in American Realism. His paintings are characterized by their clarity, precision, and remarkable attention to detail. He possessed a keen eye for observation and a patient hand, meticulously rendering textures, fabrics, architectural elements, and the nuances of human expression and posture. While realistic, his work often carries a distinct narrative quality, telling stories of everyday life, social interactions, or historical moments.

Often described as a "genre painter," Henry specialized in scenes of ordinary life, both contemporary and historical. However, his historical scenes are particularly notable, often imbued with a sense of nostalgia for earlier periods of American history, especially the colonial and post-Revolutionary eras. His European training, particularly his exposure to Courbet's realism and potentially Gleyre's emphasis on careful execution, provided a technical foundation for his detailed approach. Yet, his subject matter remained distinctly American, focusing on the nation's past and its evolving present during his lifetime.

Themes and Subjects

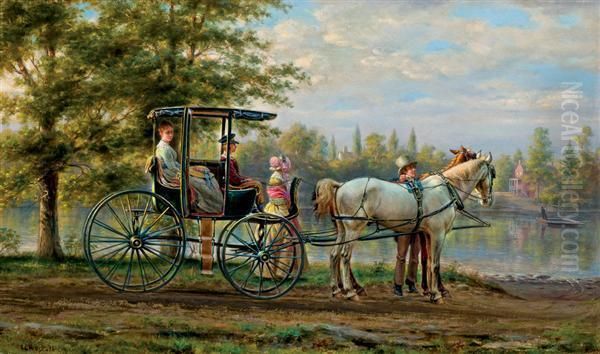

Henry's choice of subject matter was consistent throughout his career, centering on depictions of American life, particularly from the late 18th and 19th centuries. He held a deep fascination with the past, especially the era of stagecoaches, canals, and the dawn of the railroad age. Transportation became a recurring motif in his work, reflecting the significant changes occurring in American society and landscape during the 19th century.

His canvases often feature scenes set in rural villages, country stores, along canals, or featuring early modes of transport. He depicted stagecoaches arriving at inns, families traveling by carriage, canal boats navigating waterways, and some of the very first railroad trains. Beyond transportation, Henry captured intimate moments of social life: conversations on porches, gatherings in parlors, moments of quiet contemplation, and scenes hinting at village gossip or community events. Architecture also played a significant role, with careful renderings of colonial homes, taverns, and public buildings, often based on specific historical structures.

Methodology: The Historian's Eye

What truly set E.L. Henry apart was his rigorous approach to historical accuracy, which bordered on the methods of a historian or archaeologist. He was an avid collector of antiques and historical artifacts from a young age, a passion that directly fueled his art. His studio was reportedly filled with period furniture, costumes, tools, horse-drawn vehicles, architectural fragments, and ephemera. He didn't just imagine the past; he reconstructed it using tangible evidence.

Henry meticulously researched the periods he depicted. He collected photographs, prints, and documents related to historical events, architecture, and modes of transportation. When painting a scene involving a specific building or vehicle, he would often work from detailed sketches, photographs, or even salvaged pieces of the original structure if it had been demolished. This dedication to authenticity gives his paintings a documentary value, preserving visual details of American life that might otherwise have been lost. He wasn't just painting history; he was actively engaged in preserving its material culture through his research and collections.

Key Representative Works

Edward Lamson Henry's extensive body of work includes many paintings that exemplify his style and thematic interests. Among his most celebrated and representative pieces is The First Railroad Train on the Mohawk and Hudson Road (painted 1892-1893, depicting the 1831 event). This work captures the excitement and novelty of early rail travel, meticulously detailing the unique design of the DeWitt Clinton engine and its stagecoach-like carriages, set against a carefully rendered landscape. It showcases his interest in transportation history and his ability to recreate a specific historical moment with convincing detail.

Other notable works explore rural and village life. The Latest Village Scandal (1885) and Stopping for a Chat at the Gate (1887-1891) are excellent examples of his genre scenes, capturing moments of social interaction with nuanced character depiction and detailed settings. Waiting for the Ferry, Shelter Island, New York (1895) presents a tranquil scene of coastal life, highlighting his skill in rendering atmosphere and specific locales.

His interest in historical architecture is evident in paintings like The Hancock House (1863), which documented a famous Boston landmark before its demolition. Works such as The Conversation (1882), Testing His Age (1883), A Moment of Peril (1889), A Summer Day (1890), An Informal Call (c. 1894), and The Country Store (19th Century) further illustrate his focus on everyday life, transportation, and social customs of the past, all rendered with his characteristic precision and historical sensitivity.

Exhibitions and Recognition

Throughout his long career, E.L. Henry achieved considerable recognition and exhibited his work widely. Starting in 1861, he became a regular exhibitor at the annual exhibitions of the National Academy of Design in New York, a primary venue for American artists to showcase their work. He also frequently showed paintings at the Brooklyn Art Association between 1863 and 1884, and his work appeared at other prestigious venues like the Boston Athenaeum.

Henry's reputation extended beyond national borders. He participated in major international expositions, including the Paris Exposition Universelle in 1878 and 1889. His work was also featured prominently in significant American fairs, where he often received awards and accolades. These included the World's Columbian Exposition in Chicago (1893), the Pan-American Exposition in Buffalo (1901), the South Carolina Inter-State and West Indian Exposition in Charleston (1902), and the Louisiana Purchase Exposition in St. Louis (1904). This consistent presence at major exhibitions cemented his status as a leading painter of American life. Even after his death, his work continued to be celebrated, with retrospective exhibitions such as one held at the Century Association in New York in 1947 and another focusing on his work at the Yale University Art Gallery in 2005.

Contemporaries and Connections

Edward Lamson Henry operated within a rich network of artists during a dynamic period in American art. His teachers, Walter M. Opper in Philadelphia, and Charles Gleyre and Gustave Courbet in Paris, provided foundational influences. In New York, his studio in the Tenth Street Studio Building placed him in the company of major figures like the landscape painter Albert Bierstadt. While known for his grand Western scenes, Bierstadt was also reportedly a collector of Henry's work, indicating mutual respect within the artistic community.

Henry's success also attracted prominent patrons, including members of the influential Astor family, such as William Astor, who were significant collectors and supporters of the arts in New York. Other notable artists active during Henry's career, and with whom he likely had professional or social connections through institutions like the NAD or shared exhibition venues, include John La Farge, known for his murals and stained glass; William Merritt Chase, a leading Impressionist and influential teacher; Frederick Dielman, an illustrator and painter; Lockwood de Forest, known for his design work and association with Louis Comfort Tiffany; the genre painter Thomas Waterman Wood (though the provided source mentions a Thomas Waterman Moss, Wood is a more prominent contemporary genre painter); and the financier and collector James W. Drexel. Henry was thus an active participant in the artistic life of his time, respected by peers and patrons alike.

Anecdotes and Personal Life

Beyond his formal artistic career, certain anecdotes highlight E.L. Henry's personality and passions. His lifelong fascination with antiques was more than just a research method; it was a deep-seated personal interest that shaped his life and environment. His dedication to historical accuracy extended to actively preserving physical remnants of the past. He was known to collect architectural fragments from buildings slated for demolition, incorporating these tangible pieces of history into his personal collection and sometimes referencing them in his art, demonstrating a commitment to preservation that complemented his painted depictions.

His Civil War service, though non-combatant, left a lasting impression and provided a direct link to a pivotal period he would later depict. Even in death, his connection to his life's work was symbolized. Edward Lamson Henry passed away from pneumonia in 1919. His tombstone was reportedly designed in the shape of an artist's palette, a fitting final tribute to a life devoted to the art of painting and the meticulous chronicling of American history.

Legacy and Conclusion

Edward Lamson Henry occupies a unique and enduring place in American art. He was more than just a skilled painter executing realistic scenes; he was a visual historian, driven by a profound interest in the American past and a desire to capture it with fidelity before it faded from memory. His works offer invaluable glimpses into the social customs, architecture, transportation, and atmosphere of 18th and 19th-century America.

His meticulous research methods and reliance on historical artifacts lend his paintings a distinct authenticity. While some later art movements moved away from his detailed realism, Henry's work has retained its appeal for its narrative charm, technical skill, and historical significance. He successfully documented aspects of American life and technological change – the transition from stagecoach to railroad, the character of rural communities, the look and feel of colonial times – preserving them for future generations. Edward Lamson Henry remains celebrated as a dedicated chronicler of bygone America, whose canvases continue to educate and enchant viewers with their detailed and heartfelt depictions of the nation's heritage.