William Michael Harnett stands as a pivotal figure in late nineteenth-century American art. An immigrant who achieved remarkable fame, he became the foremost practitioner of a highly realistic style of still life painting known as trompe-l'oeil, or "fool the eye." His meticulously rendered depictions of everyday objects captivated the public and continue to fascinate viewers today, blurring the lines between painting and reality. Though his critical standing fluctuated during his life and after, his technical brilliance and unique vision have secured his place as a significant contributor to the history of American realism.

From Ireland to Philadelphia: Early Life and Artistic Beginnings

William Michael Harnett was born in Clonakilty, County Cork, Ireland, on August 10, 1848. His childhood coincided with the devastating Great Famine, a period of mass starvation, disease, and emigration. Like countless others seeking refuge and opportunity, the Harnett family emigrated to the United States, settling in the bustling city of Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. This city, with its rich artistic and cultural heritage, would become the crucible for Harnett's early development.

Showing an early aptitude for detailed work, Harnett initially pursued a trade rather than fine art. He began his professional life as an engraver, specifically working on silverware designs. This craft demanded precision, a keen eye for detail, and a steady hand – skills that would prove foundational to his later painting technique. Engraving intricate patterns onto metal surfaces honed his ability to render texture and form with exacting accuracy.

Despite his work as an artisan, Harnett harbored ambitions for a career in fine art. He sought formal training to develop his talents, enrolling in evening classes at the prestigious Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts (PAFA). Founded in 1805, PAFA was a cornerstone of American art education, providing students with access to casts of classical sculptures and opportunities for life drawing. Harnett diligently pursued his studies while supporting himself through engraving.

Seeking further instruction and exposure to different artistic environments, Harnett later moved to New York City. There, he continued his artistic education, studying at the Cooper Union for the Advancement of Science and Art and subsequently at the National Academy of Design. Both institutions were vital centers for artistic training in the city. His time in New York broadened his horizons and likely exposed him to a wider range of contemporary art and artists, further shaping his artistic direction. By 1868, he had formalized his connection to his adopted country by becoming a United States citizen.

The Emergence of a Trompe-l'oeil Painter

During the 1870s, Harnett made the decisive shift from engraving to painting full-time. He focused his energies on still life, a genre with a long history but one that he would approach with a distinctive, illusionistic intensity. His early training as an engraver clearly informed his meticulous painting style, characterized by sharp focus, precise rendering of textures, and a careful handling of light and shadow.

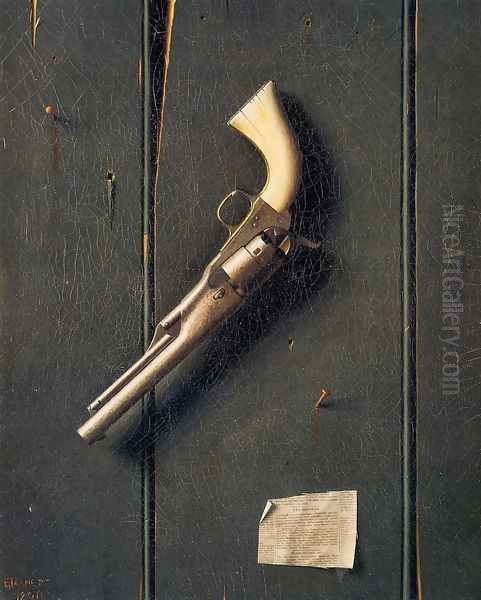

His chosen subjects were often humble, everyday objects drawn from the masculine world of the late nineteenth century: well-thumbed books, musical instruments (especially violins and flutes), smoking pipes, beer mugs, horseshoes, firearms, hunting gear, and even currency. He arranged these items in carefully considered compositions, typically against shallow, neutral backgrounds like wooden tabletops or doors, enhancing the sense of tangible reality.

Harnett quickly gained recognition for his astonishing ability to mimic reality. His paintings were not merely realistic; they aimed to deceive the viewer into believing the depicted objects were physically present. This trompe-l'oeil approach, while having roots in Greco-Roman antiquity and flourishing in 17th-century Dutch art, found a particularly receptive audience in Gilded Age America, a society fascinated by materialism, technical ingenuity, and visual spectacle.

His works began to sell well, providing him with a degree of financial independence. The public was enthralled by the sheer verisimilitude of his paintings. Anecdotes abound of viewers attempting to grasp the objects depicted, a testament to the success of his illusionistic technique. This popular acclaim, however, was not always matched by critical approval from the established art world, which sometimes dismissed trompe-l'oeil as mere technical trickery lacking deeper artistic merit.

Masterworks of Illusion: Signature Paintings

Throughout his relatively short but productive career, Harnett created several works that have become icons of American still life painting. These paintings exemplify his mature style and his mastery of the trompe-l'oeil technique.

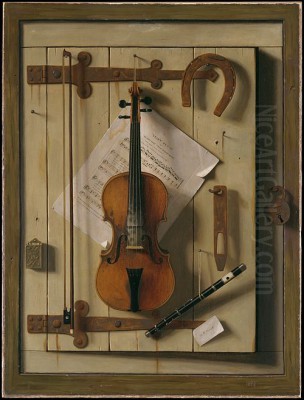

The Old Violin (1886): Perhaps Harnett's most famous painting, The Old Violin depicts a weathered violin and bow hanging vertically against a hinged wooden door. A small newspaper clipping and a blue envelope are tucked behind the strings. The realism is breathtaking: the grain of the wood, the rosin dust on the strings, the worn varnish of the instrument, the texture of the paper, even the shadows cast by the objects, are rendered with uncanny precision. Its exhibition reportedly caused crowds to gather, debating whether the violin was real or painted, cementing Harnett's reputation as a master illusionist.

After the Hunt (Series, notably 1883, 1885): This theme, which Harnett revisited in several large-scale versions, represents the pinnacle of his complex compositional arrangements. The paintings typically depict an assemblage of hunting equipment – rifles, a powder horn, a hunting cap, a canteen, a game bird or rabbit – hanging from hooks against a rustic wooden door. The intricate interplay of textures (metal, wood, feather, fur, leather), the complex overlapping of forms, and the convincing depiction of three-dimensional space make these works tour-de-forces of realistic painting. The versions painted during his time in Munich were particularly celebrated.

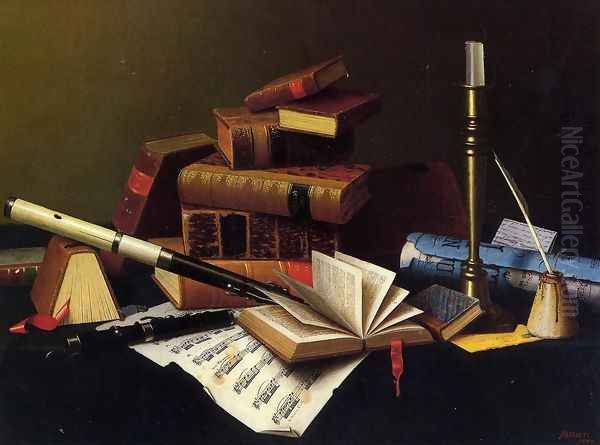

My Gems (1888): In contrast to the masculine themes of hunting, My Gems focuses on objects associated with culture and leisure. It features a collection of well-loved books stacked horizontally, a flute resting atop them, a small ceramic pitcher, and a sheet of music. The title suggests a personal connection to these items. The painting showcases Harnett's ability to render diverse textures – the brittle pages of books, the smooth wood of the flute, the glazed surface of the pitcher – with equal fidelity. The composition is tight and balanced, drawing the viewer into an intimate space.

Music and Literature (various versions): Similar to My Gems, this theme explores cultural pursuits. Harnett often combined musical instruments like violins or flutes with books, sheet music, and sometimes inkwells or pipes. These compositions highlight the textures of aged paper, worn leather bindings, and polished wood, often evoking a sense of quiet contemplation or the passage of time through the depiction of well-used objects.

Still Life - Violin and Music (1888): Another variation on a favorite theme, this work, now in the Metropolitan Museum of Art, again features a violin, bow, and sheet music, arranged on a tabletop. The meticulous detail extends to the printed notes on the music sheet and the subtle reflections on the violin's varnish. It demonstrates his consistent ability to create convincing illusions through careful observation and painstaking execution.

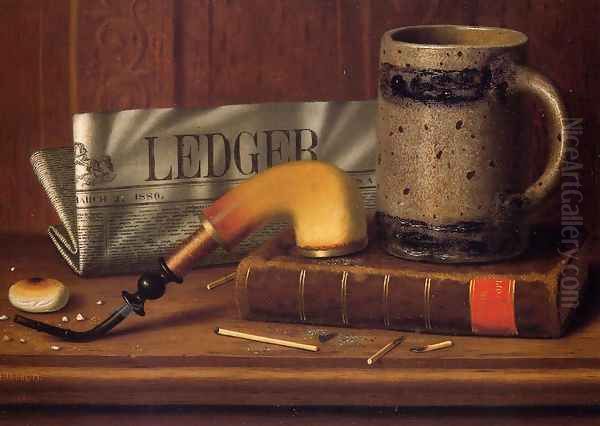

Philadelphia Public Ledger (1880): An earlier work, this painting demonstrates his skill with depicting paper currency and printed materials. It features a copy of the newspaper, coins, and other ephemera arranged on a surface. Paintings involving currency were popular but sometimes drew scrutiny from authorities concerned about counterfeiting, highlighting the provocative nature of extreme realism.

These representative works showcase the core elements of Harnett's style: an obsessive attention to detail, a mastery of light and shadow to create volume, a preference for shallow space to enhance the illusion, and a focus on the textures and surfaces of the material world.

Themes and Subjects: More Than Meets the Eye

While the immediate impact of Harnett's work lies in its astonishing realism, his paintings often contain deeper layers of meaning and explore recurring themes. His choice of objects was deliberate, reflecting the interests and values of his time, particularly those associated with middle-class American masculinity.

Material Possessions and Daily Life: Harnett's paintings are inventories of the objects that populated the studies, parlors, and offices of his contemporaries. Books, pipes, mugs, musical instruments, and hunting gear were markers of leisure, culture, and social standing. By rendering these items with such care, Harnett elevated the commonplace to the realm of art, inviting viewers to contemplate the significance of the material world.

The Passage of Time: Many of the objects Harnett depicted show signs of wear and tear – dog-eared books, chipped mugs, scratched violin varnish, rusted horseshoes. This emphasis on imperfection and use imbues the paintings with a sense of nostalgia and melancholy, hinting at the transience of material things and the lives of their owners. The objects become silent witnesses to history and human activity.

Masculinity and Leisure: The prevalence of hunting gear, smoking paraphernalia, and musical instruments often associated with male pastimes reflects the gendered social norms of the era. Works like After the Hunt can be seen as celebrations of masculine pursuits and the spoils of outdoor activity, presented almost as trophies.

Culture and Intellect: The frequent inclusion of books, sheet music, and musical instruments points to an appreciation for cultural and intellectual life. These objects symbolize learning, creativity, and refined taste. Paintings like My Gems or Music and Literature create intimate portraits of a cultured existence.

Illusion versus Reality: At its core, Harnett's trompe-l'oeil art is a playful yet profound exploration of the nature of perception and representation. By challenging the viewer's ability to distinguish between the painted and the real, Harnett raises questions about the reliability of sight and the power of art to mimic life. His work engages in a dialogue about artifice and authenticity that remains relevant.

European Sojourn and Later Years

Seeking to broaden his artistic experience and perhaps gain greater recognition, Harnett traveled to Europe in 1880. He spent a significant period, from 1880 to 1884, in Munich, a major European art center known for its strong academic tradition and interest in realism. It was during his time in Munich that he painted some of the most ambitious versions of his After the Hunt theme, which were exhibited to acclaim. He also spent time in London and possibly Paris before returning to the United States in 1886.

Upon his return, Harnett settled back in New York City. He continued to paint, producing some of his most refined works, including The Old Violin. However, his later years were increasingly hampered by ill health. He suffered from debilitating rheumatism and kidney disease, which often forced him to stop working for periods. In 1887, seeking relief, he traveled to Hot Springs, Arkansas, known for its therapeutic waters, but found little lasting improvement.

Despite his physical ailments, he continued to paint when he could, maintaining his meticulous technique. His reputation among the public remained high, and his works commanded respectable prices. However, the physical toll of his illness was significant. William Michael Harnett died relatively young, at the age of 44, in New York City on October 29, 1892.

Harnett in Context: Influences and Contemporaries

Harnett did not work in isolation. His art was informed by historical precedents and resonated with the work of several contemporaries, both influencing and being influenced by the artistic currents of his time.

Artistic Influences: Harnett's meticulous realism and choice of subject matter show a clear affinity with 17th-century Dutch and Flemish still life painters. Masters like Pieter Claesz, Willem Claesz. Heda, and Willem Kalf excelled in depicting arrangements of tableware, food, and symbolic objects with remarkable detail and textural accuracy. Harnett adapted their precision and focus on the tangible world to an American context. He was also likely aware of the work of earlier American still life painters, particularly the Peale family of Philadelphia. Raphaelle Peale and James Peale, working earlier in the 19th century, had established a tradition of American still life known for its clarity and directness, which provided a foundation for later artists like Harnett. The detailed realism of Charles Bird King's still lifes may also have been an influence. The French master Jean-Baptiste-Siméon Chardin, known for his quiet, intimate still lifes of humble objects, represents another potential, though less direct, point of reference in the broader history of the genre.

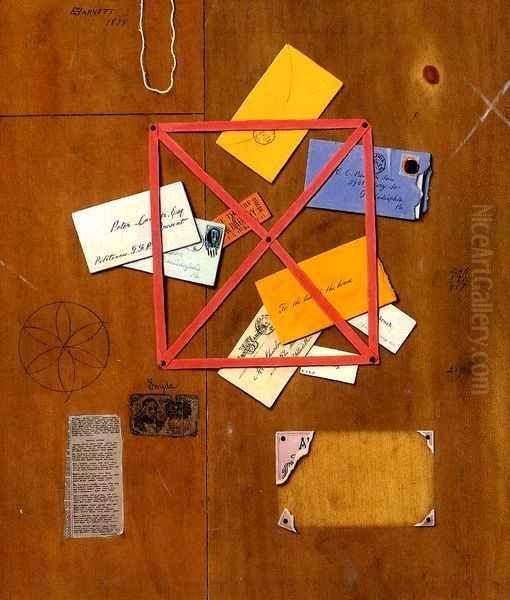

Friendship with Henry Tatnall: Harnett maintained friendships within the artistic community. One documented friendship was with the Wilmington-based painter Henry Harry Lea Tatnall. As a gesture of thanks for Tatnall's hospitality during a stay in the 1870s, Harnett painted a still life for him, cleverly incorporating a realistically painted envelope addressed to Tatnall within the composition, blending personal connection with his signature illusionism.

Relationship with John F. Peto: Harnett's most significant relationship with a contemporary artist was arguably with John Frederick Peto. Peto met Harnett while studying at the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts (where Peto was enrolled intermittently between 1878 and 1889). The two became friends, and Harnett's established success with trompe-l'oeil profoundly influenced Peto's artistic direction. While Peto developed his own distinct style – often characterized by softer light, more worn and discarded objects, and a more melancholic mood – the foundational impact of Harnett is undeniable. Their styles were similar enough that, after Peto's death (and during a period when Harnett's fame eclipsed Peto's), unscrupulous dealers sometimes forged Harnett's signature onto Peto's paintings to increase their market value. This unfortunate practice underscores the close association, both stylistic and personal, between the two artists.

The Trompe-l'oeil School: Harnett was the leading figure in a flourishing school of American trompe-l'oeil painters active in the late 19th century. Other notable practitioners included John Haberle, known for his incredibly detailed depictions of currency and stamps, often pushing the boundaries of illusionism with playful and complex compositions. Jefferson David Chalfant also worked in a highly realistic vein, sometimes creating trompe-l'oeil still lifes alongside genre scenes. Other artists associated with this trend include George Cope, Alexander Pope, De Scott Evans, and Victor Dubreuil, each contributing to the popularity of illusionistic still life during this period. Harnett's work set a high standard and served as a major inspiration for these artists.

Critical Reception: From Dismissal to Rediscovery

The critical assessment of William Michael Harnett's work has undergone a significant transformation over time. During his lifetime, he achieved considerable popular success and financial reward. The public marveled at his technical skill and the uncanny realism of his paintings. His works were widely exhibited and eagerly collected.

However, mainstream art critics and the academic art establishment often held a more reserved, sometimes dismissive, view. In an era increasingly influenced by European trends like Impressionism and movements emphasizing painterly brushwork and subjective expression, Harnett's tight, meticulous style was sometimes seen as overly literal and lacking in artistic imagination. Critics occasionally derided trompe-l'oeil as mere craftsmanship or visual trickery, devoid of the higher aesthetic or emotional qualities they valued in fine art. His work was sometimes labeled as simple imitation rather than creative interpretation.

Following his death in 1892, Harnett's reputation, along with that of the trompe-l'oeil school in general, gradually faded. The rise of modernism in the early 20th century, with its emphasis on abstraction, expressionism, and formal innovation, pushed realistic traditions like Harnett's further into the background. For several decades, he was largely overlooked by art historians and major museums.

The tide began to turn around the mid-20th century. A pivotal moment came with a retrospective exhibition organized by the Downtown Gallery in New York in 1939, curated by Edith Gregor Halpert, which reintroduced Harnett and his contemporary John F. Peto to a new generation. This exhibition sparked renewed interest among critics, collectors, and scholars.

Art historians began to re-evaluate Harnett's work, looking beyond the surface illusionism. They recognized his sophisticated compositional skills, his mastery of form and texture, and the psychological resonance of his chosen objects. Critics like Alfred Frankenstein undertook extensive research, distinguishing Harnett's work from that of his followers (like Peto, whose works had often been misattributed to Harnett) and highlighting Harnett's unique contributions. His paintings came to be appreciated not just for their technical virtuosity but also for their abstract qualities of design and their poignant reflection of American life in the Gilded Age. He was increasingly recognized as a major figure in the history of American realism.

Legacy and Enduring Appeal

Today, William Michael Harnett is firmly established as one of the most important American still life painters of the 19th century. His work is held in major museums across the United States, including the Metropolitan Museum of Art, the National Gallery of Art, the Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco, and the Art Institute of Chicago.

His legacy lies primarily in his mastery of the trompe-l'oeil technique, which he practiced with unparalleled skill and dedication. He demonstrated that meticulous realism could be a powerful vehicle for artistic expression, capable of engaging viewers on both intellectual and visceral levels. His paintings continue to captivate audiences with their astonishing illusionism and their evocative portrayal of everyday objects.

Harnett's influence extended to his contemporaries within the trompe-l'oeil school and arguably resonated with later artists interested in realism and illusion, perhaps even finding echoes in aspects of Surrealism's fascination with the uncanny juxtaposition of objects and the blurring of reality. He elevated American still life painting, bringing to it a level of technical brilliance and popular appeal that was unprecedented.

William Michael Harnett's art remains a compelling window into the material culture and aesthetic sensibilities of late 19th-century America. His paintings are more than just visual tricks; they are carefully constructed meditations on objects, time, and the very nature of artistic representation. As a master of illusion, he secured a unique and enduring place in the annals of American art history.