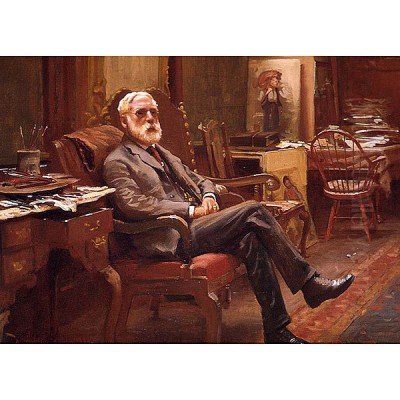

Gilbert Gaul stands as a significant figure in American art history, an artist whose canvases captured the dramatic intensity of military conflict and the evolving narrative of the American West during the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. Born in Jersey City, New Jersey, in 1855, Gaul's life spanned a period of profound transformation in the United States, and his work reflects the nation's grappling with its recent past and its expansionist present. Trained in the established academies of New York City, he quickly rose to prominence, yet his legacy is primarily tied to his powerful, realistic depictions of soldiers, Native Americans, and frontier life. This exploration delves into the life, career, artistic style, and enduring impact of Gilbert Gaul, an artist dedicated to chronicling the American experience.

Early Life and Artistic Formation

William Gilbert Gaul entered the world on March 31, 1855. His artistic inclinations led him to New York City, the burgeoning center of the American art world. There, he sought formal training, enrolling first at the prestigious National Academy of Design (NAD). The NAD, founded decades earlier by figures like Samuel F.B. Morse and Thomas Cole, represented the established tradition of American art, emphasizing drawing skills and academic principles. Gaul studied under Lemuel E. Wilmarth, a respected painter and influential teacher who served as the Director of the Academy school for many years. Wilmarth's instruction would have provided Gaul with a solid foundation in academic technique.

Following his time at the NAD, Gaul continued his studies at the Art Students League of New York (ASL). The ASL offered a more progressive and artist-run alternative to the Academy, often attracting students seeking different approaches. Here, Gaul came under the tutelage of John George Brown. Brown, an English-born painter who achieved immense popularity for his sentimental depictions of New York City street urchins, particularly bootblacks and newsboys, had a discernible impact on Gaul's early work. While Gaul would eventually move towards more dramatic and historical subjects, the narrative quality and focus on everyday figures seen in Brown's work likely resonated with the young artist, perhaps influencing his later attention to the individual experiences within larger historical events. This combination of rigorous academic training and exposure to popular genre painting equipped Gaul with both the technical skill and the narrative sensibility that would define his career.

Ascending the Ranks: Recognition and Illustration

Gaul's talent was recognized relatively early in his career. He began exhibiting at the National Academy of Design in the late 1870s. His skill and dedication earned him election as an Associate of the NAD (ANA) in 1879. Just three years later, in 1882, at the remarkably young age of twenty-seven, Gilbert Gaul was elected a full Academician (NA). This was a significant honor, making him one of the youngest artists ever to achieve this status at the Academy, a testament to the high regard in which his peers held his work. This early success placed him firmly within the mainstream of the American art establishment.

Beyond the world of gallery exhibitions, Gaul, like many artists of his time, found a powerful outlet and source of income in illustration. The late nineteenth century was a golden age for illustrated magazines in America. Publications like Harper's Weekly and The Century Magazine (formerly Scribner's Monthly) reached vast audiences, shaping public opinion and visual culture. Gaul became a regular contributor, translating his paintings and creating original drawings for reproduction. This work not only provided financial stability but also brought his depictions of military life and Western scenes into countless American homes, significantly broadening his fame and influence beyond the confines of the art world. His ability to create compelling, narrative images made him a sought-after illustrator, placing his work alongside that of other prominent illustrators of the era, such as Howard Pyle and Winslow Homer, who also frequently contributed to these major periodicals.

Chronicler of the Civil War

While his early work included genre scenes potentially influenced by John George Brown, Gilbert Gaul soon found his most enduring subject matter: the American Civil War. Though too young to have experienced the conflict firsthand, he dedicated himself to recreating its scenes with remarkable fidelity and emotional depth. The decades following the war saw a surge of interest in commemorating and understanding the conflict, creating a receptive audience for Gaul's meticulously researched paintings. His work resonated with veterans and the public alike, offering vivid glimpses into the experiences of the common soldier.

To ensure the accuracy that became a hallmark of his military art, Gaul went to great lengths. He established a studio for a time in McMinnville, Tennessee, placing himself in the heart of a region that had seen significant Civil War action. More importantly, he became an avid collector of military artifacts – uniforms, weapons, and equipment from the period. This hands-on research allowed him to depict the details of camp life, marches, and battles with a high degree of authenticity, lending credibility and power to his historical reconstructions. This dedication to research set him apart and contributed significantly to the respect his work commanded.

Gaul's Civil War paintings covered a range of experiences. Works like Charging the Battery captured the terrifying dynamism and chaos of battle, depicting soldiers advancing under fire. Others, such as Wounded to the Rear, focused on the human cost of conflict, showing the suffering and camaraderie of injured soldiers being helped away from the front lines. The Stragglers depicted the exhaustion and hardship of soldiers falling behind on a march, while Those Dreary Days likely evoked the monotony and difficult conditions of camp life or prolonged campaigns. These paintings were not merely illustrations of events; they aimed to convey the atmosphere, the psychological toll, and the lived reality of the war for the ordinary men who fought it.

His commitment to the subject and his skill in rendering it brought continued recognition. One of his most celebrated Civil War paintings, The Firing Line, earned him a gold medal at the Appalachian Exposition held in Knoxville, Tennessee, in 1910. This award, coming decades after the war itself, underscored the lasting power of his depictions. He also received accolades at major international exhibitions, including a gold medal at the prestigious World's Columbian Exposition in Chicago in 1893, further cementing his reputation. While other artists like Winslow Homer also addressed the Civil War, Homer's work often carried a more profound psychological weight or focused on the war's aftermath. Eastman Johnson depicted detailed scenes of camp life. Gaul's particular strength lay in his combination of detailed realism, narrative clarity, and focus on the collective experience of soldiers in action or enduring hardship.

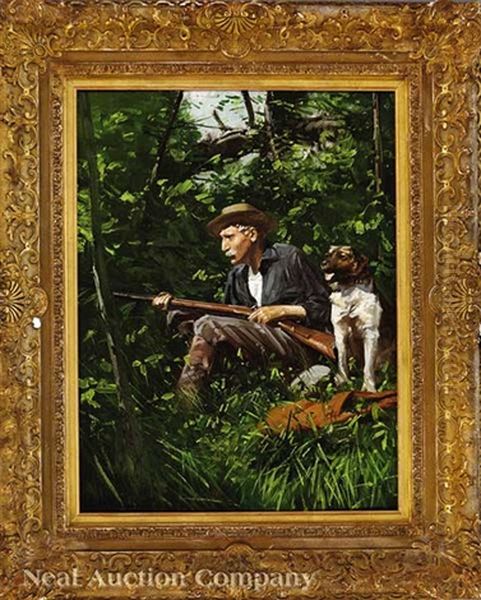

Picturing the American West

Parallel to his interest in military history, Gilbert Gaul developed a deep fascination with the American West. Like many artists of his generation, he was drawn to the landscapes, peoples, and unfolding drama of the frontier. He undertook several trips westward, venturing into territories inhabited by Native American tribes and observing the life of cowboys and settlers. These journeys provided him with firsthand material for a significant body of work that documented a region undergoing rapid change. His Western paintings, like his military scenes, were characterized by a commitment to observation and realistic detail.

Gaul's depictions of Native Americans are particularly noteworthy. He traveled to reservations and observed daily life, capturing scenes of camps, hunts, and ceremonies. Significantly, he was commissioned by the federal government as part of a project for the Eleventh U.S. Census in 1890. His role involved creating illustrations for a planned visual catalog of Native American tribes. This project, though perhaps never fully realized in its intended published form, involved documenting various aspects of Native life, including dwellings. Gaul recorded the visual evidence of cultural transition, noting, for instance, the shift from traditional animal-hide tipis to those made of canvas issued by the government. This attention to ethnographic detail provides valuable historical insight, distinguishing his work from purely romanticized portrayals of Native Americans. While artists like George Catlin and Karl Bodmer had documented Plains Indian cultures earlier in the century, and contemporaries like Frederic Remington and Charles Schreyvogel were becoming famous for their action-packed Western scenes, Gaul offered a quieter, more observational perspective focused on the realities of reservation life and cultural adaptation.

Beyond Native American subjects, Gaul also painted scenes of cowboy life, settlers, and the Western landscape itself. While perhaps less focused on the dramatic action often associated with Remington, Gaul's work captured the atmosphere of the plains and the character of its inhabitants. His Western landscapes, though perhaps secondary to his figurative work, depicted the vastness and specific quality of light found in the region. Unlike the often monumental and sublime landscapes of Albert Bierstadt or Thomas Moran, Gaul's Western settings usually served as backdrops for human activity, consistent with his primary interest in narrative and the human figure within their environment. His Western work, taken as a whole, contributes significantly to the visual record of the American West in the late nineteenth century.

Beyond the Battlefield and Frontier: Genre and Landscape

While best known for his military and Western themes, Gilbert Gaul's artistic output was more diverse. He continued to produce genre scenes throughout his career, depicting moments of everyday life, often with a narrative or sentimental quality that perhaps echoed the influence of his former teacher, John George Brown. Works like Waiting (an early piece) or Girl with Flowers suggest an interest in capturing quieter, more personal moments. These paintings often focused on rural or working-class figures, reflecting a broader trend in American art of the period, seen also in the work of artists like Eastman Johnson. Gaul's genre paintings demonstrate his versatility and his ability to find compelling subjects beyond the high drama of war and the frontier.

His travels also provided inspiration for landscapes and scenes set outside the continental United States. He journeyed to Mexico, Panama, and the West Indies, sketching and painting the local scenery and inhabitants. These works broadened his geographical scope and likely introduced different palettes and light effects into his art. His landscapes, whether depicting the rolling hills of Tennessee, such as in Tennessee Road or Rafting on the Cumberland River, or the more exotic locales of his travels, were generally rendered in his characteristic realistic style. While not primarily known as a landscape painter in the vein of the Hudson River School masters or later Impressionists like Childe Hassam or William Merritt Chase, his landscape work forms an integral part of his oeuvre, showcasing his observational skills and his ability to capture a sense of place.

Artistic Method and Signature Style

Gilbert Gaul's art is firmly rooted in the tradition of American Realism. His primary goal was to depict his subjects – whether soldiers, Native Americans, or rural folk – with accuracy and convincing detail. This commitment stemmed from his academic training and was reinforced by his meticulous research methods, particularly his collection of artifacts for his Civil War paintings and his direct observation during travels West. He possessed strong draftsmanship skills, allowing him to render figures, animals, and environments with clarity and precision.

His compositions are typically narrative, designed to tell a story or convey a specific moment in time. He arranged figures and elements carefully to create focal points and guide the viewer's eye through the scene. Whether depicting the chaos of battle or the quietude of a camp, his paintings have a sense of immediacy, drawing the viewer into the depicted event. His use of color was generally naturalistic, aiming to reproduce the effects of light and atmosphere accurately. While not an Impressionist concerned with capturing fleeting moments of light, he was skilled at rendering textures, the play of sunlight and shadow, and the overall mood of a scene.

Beyond technical accuracy, Gaul imbued his work with a strong emotional component. His soldiers often display fatigue, determination, or suffering. His depictions of Native Americans, while observational, could also convey dignity or a sense of cultural persistence amidst change. He sought to capture the human element within historical events and everyday life. This combination of detailed realism, narrative clarity, and emotional resonance defines the signature style of Gilbert Gaul's work, making his paintings accessible and compelling records of American life during his era. He stood somewhat apart from the more painterly realism of Thomas Eakins or the burgeoning Impressionist movement championed by artists like Julian Alden Weir, adhering instead to a more illustrative and narrative form of realism.

Later Career, Challenges, and Enduring Legacy

Despite his early success and continued productivity, Gilbert Gaul's reputation faced challenges in the later part of his career. By the early twentieth century, artistic tastes began to shift. The rise of Modernism in Europe and its gradual influence in America led to a decreased interest in the kind of historical and narrative realism that Gaul practiced. The heroic themes of the Civil War, once a subject of intense national interest, gradually lost their appeal to newer generations and collectors more attuned to contemporary life or avant-garde styles.

Furthermore, the nature of warfare itself was changing dramatically. While Gaul had documented the American West and had some experience observing military maneuvers, he did not achieve significant artistic commissions or recognition related to the Spanish-American War or, later, World War I. The scale and industrialized nature of twentieth-century conflict perhaps lay outside the scope of his established artistic approach, which excelled at depicting the more personal, human scale of nineteenth-century warfare. Consequently, his prominence in the art world began to fade somewhat in his later years.

Gilbert Gaul spent his final years living in Ridgefield, New Jersey, not far from his birthplace, and later moved to New York City before passing away in 1919. While his fame may have diminished during his lifetime compared to his peak years, his contribution to American art remains significant. He stands as one of the foremost painters of the American Civil War, creating a body of work valued for its historical accuracy and its empathetic portrayal of the common soldier. His Western paintings provide an important visual record of Native American life and the frontier during a critical period of transition. Through his numerous illustrations, he reached a vast public audience, helping to shape the popular visual understanding of American history and identity. Though perhaps overshadowed in art historical narratives by innovators like Winslow Homer or the Western mythmakers like Frederic Remington, Gilbert Gaul's dedicated realism and narrative skill carved out a unique and valuable place in the story of American art. His paintings continue to be studied and appreciated for their artistry and as historical documents chronicling a nation's defining conflicts and transformations.

Conclusion

Gilbert Gaul navigated the American art world of the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries with considerable skill and dedication. From his academic training under notable figures like Lemuel Wilmarth and John G. Brown to his rapid ascent within the National Academy of Design, he established himself as a talented and respected artist. His true legacy, however, lies in his chosen subject matter. As a meticulous chronicler of the American Civil War and an observant painter of the American West, Gaul created a powerful and enduring visual record of pivotal aspects of the nation's experience. His commitment to realism, his narrative clarity, and his ability to convey the human dimension of historical events ensure his continued relevance. While artistic fashions changed during his lifetime, the body of work left by Gilbert Gaul remains a significant contribution, offering invaluable insights into the soldiers, landscapes, and peoples that shaped America during a transformative era.