Elioth Lauritz Leganyer Gruner stands as one of Australia's most celebrated landscape painters of the early twentieth century. Born not in Australia but in Gisborne, New Zealand, on December 16, 1882, his destiny was nonetheless intertwined with the sun-drenched landscapes of his adopted homeland. His family, comprising his Norwegian father, Elliott Grüner, a bailiff, and his Irish mother, Mary Ann Brennan, relocated to Sydney, Australia, in 1883, when Elioth was merely an infant. This move set the stage for a life dedicated to capturing the unique essence and luminous quality of the Australian environment.

Gruner's artistic inclinations surfaced early in his life. Recognizing his potential, his mother encouraged his talent. From the tender age of 12, around 1894, he began receiving formal art instruction under Julian Ashton at the Art Society of New South Wales (later the Julian Ashton Art School). Ashton, a pivotal figure in the Sydney art scene and a champion of plein-air painting, became a crucial mentor, shaping Gruner's early development and instilling in him the importance of direct observation from nature. Ashton's school was a hub for aspiring artists, placing Gruner within a stimulating environment that included figures associated with Ashton like Norman Lindsay.

Early Life and Artistic Beginnings

The path to becoming a full-time artist was not immediate for Gruner. Family circumstances required him to contribute financially from a young age. At 14, he began working long hours in a draper's shop, initially as an assistant and later in a department store. This demanding work continued for many years, forcing him to pursue his passion for painting primarily during evenings and weekends. Despite these constraints, his dedication did not waver. He continued his studies with Julian Ashton whenever possible, absorbing the principles of tonal realism and the importance of capturing light effects accurately.

His persistence began to bear fruit. In 1901, Gruner achieved his first public recognition when his painting "Violets" was exhibited with the Society of Artists, Sydney. This marked a significant milestone, encouraging him to persevere. Around 1903, he made the decisive step to leave the drapery trade and dedicate more time to his art, though financial independence remained a challenge. For a period, he managed Julian Ashton's gallery and even attempted to run his own small art school to support himself, demonstrating his commitment to remaining within the art world.

The early years of the twentieth century saw Gruner steadily building his skills and reputation. He was deeply influenced by the ethos of painting outdoors, directly from the subject, a practice championed by his teacher Ashton and earlier exemplified by the Heidelberg School artists like Arthur Streeton, Tom Roberts, and Charles Conder. Gruner, however, developed his own distinct approach, less focused on narrative or nationalistic sentiment, and more intensely concentrated on the subtle interplay of light, atmosphere, and form within the landscape.

Developing a Style: The Pursuit of Light

Gruner's artistic identity became synonymous with his extraordinary ability to render the effects of light, particularly the soft, diffused light of early morning or late afternoon. He was fascinated by how light transformed the landscape, revealing textures, defining forms, and creating specific moods. His technique involved careful observation and a meticulous application of paint, often using subtle tonal gradations to convey atmospheric perspective and the delicate nuances of colour temperature. This focus distinguished him from some of the bolder, more decorative approaches emerging elsewhere in Australian art.

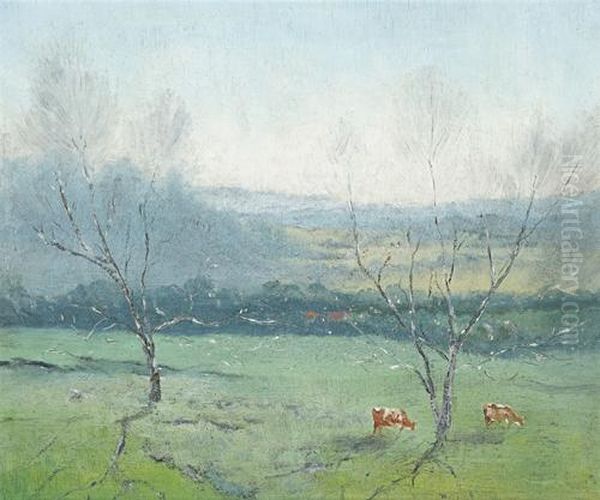

A pivotal moment in his career development occurred around 1915 when he began spending significant time painting in the Emu Plains region, west of Sydney, at the foot of the Blue Mountains. This area provided him with ample subject matter perfectly suited to his sensibilities – pastoral scenes, rolling hills, and farmland bathed in the characteristic hazy light of the region. It was here that he produced some of his most iconic early works, demonstrating a maturing vision and technical mastery.

His painting "Morning Light," created during this period and exhibited in 1916, exemplifies his focus. It captures the gentle radiance of the early sun illuminating a rural scene, showcasing his skill in handling subtle tonal shifts and creating a palpable sense of atmosphere. This work not only marked a significant artistic achievement but also brought him major public recognition when it was awarded the prestigious Wynne Prize for landscape painting by the Art Gallery of New South Wales in 1916. This was the first of an unprecedented seven Wynne Prizes he would win throughout his career.

Another significant work from this Emu Plains period was "Frosty Sunrise" (1917), which continued his exploration of atmospheric effects under specific light conditions. These early successes solidified his reputation as a leading landscape painter, one deeply attuned to the particular qualities of the Australian environment. His dedication to plein-air work was absolute; he would often rise before dawn to capture the fleeting effects of the morning light, enduring physical discomfort in his quest for authenticity.

Recognition and Acclaim: The Wynne Prize Dominance

Winning the Wynne Prize in 1916 was a turning point, elevating Gruner's status within the Australian art world. This prize, established in 1897, was (and remains) one of Australia's most important awards for landscape painting or figure sculpture, and winning it conferred significant prestige. Gruner's subsequent dominance of the award was remarkable and cemented his position as the preeminent landscape painter of his generation in the eyes of the art establishment and the public.

He won the Wynne Prize again in 1919 with arguably his most famous painting, "Spring Frost." This masterpiece, depicting a crisp, sunlit morning in the Emu Plains with frost lingering in the shadows, is celebrated for its exquisite rendering of light, its delicate colour harmonies, and its evocative atmosphere. The painting became immensely popular and is widely regarded as one of the icons of Australian art. It perfectly encapsulates Gruner's ability to combine meticulous observation with a poetic sensibility.

Gruner's Wynne Prize victories continued throughout the following decades: he won again in 1921 with "Valley of the Tweed," in 1929 with "On the Murrumbidgee," and secured further wins in 1934 ("Murrumbidgee Ranges, Canberra"), 1936 ("An Australian Landscape"), and 1937 ("Weetangera, Canberra"). This extraordinary record of seven wins remains unmatched by any other landscape painter. These awards provided not only critical validation but also crucial financial support, allowing him greater freedom to travel and paint. His success placed him alongside other respected landscape painters of the era, such as Hans Heysen, who also frequently depicted the unique qualities of Australian light and land, albeit often in different regions and with a different focus.

His consistent success at the Wynne Prize exhibitions ensured his work was regularly seen by a wide audience and acquired for major public collections, including the Art Gallery of New South Wales. Critics lauded his technical skill, his sensitivity to nature, and his ability to capture the soul of the Australian landscape. He became a benchmark against which other landscape painters were often measured during the 1920s and 1930s.

Masterworks and Signature Themes

Beyond his Wynne Prize winners, Gruner produced a significant body of work characterized by recurring themes and a consistent stylistic focus. "Spring Frost" (1919) remains perhaps his most recognized work, embodying his fascination with the transformative effects of morning light on a familiar rural scene. The painting's high viewpoint, meticulous detail in the foreground contrasted with the atmospheric haze in the distance, and the delicate balance of warm sunlight and cool shadows showcase his technical brilliance and poetic vision.

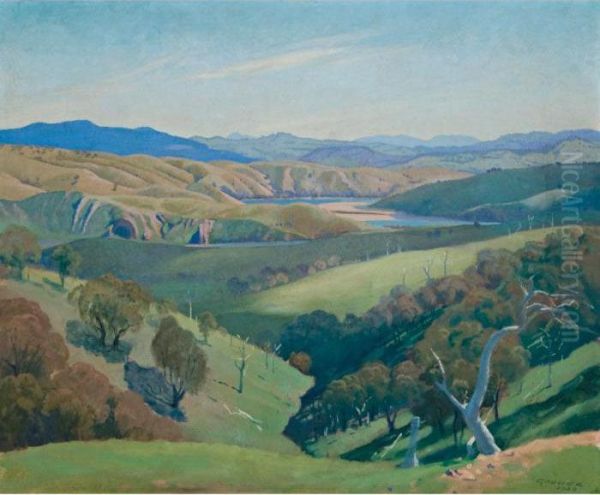

"The Valley of the Tweed" (1921), another Wynne winner, depicts a panoramic view of the lush Tweed Valley in northern New South Wales. This work demonstrates his ability to handle broader vistas, capturing the grandeur of the landscape while retaining his characteristic sensitivity to light and atmosphere. The painting conveys a sense of tranquility and timelessness, celebrating the beauty of the Australian countryside.

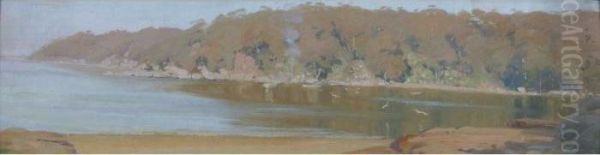

"Taylor's Bay" (c. 1913) is an earlier, more intimate coastal scene, showcasing his skill in rendering water and reflections under soft, ambient light. It possesses a quiet charm and demonstrates his versatility in tackling different types of landscapes. His coastal scenes often share the same preoccupation with light effects as his rural paintings, capturing the shimmer of sunlight on water or the subtle colours of the shoreline at different times of day.

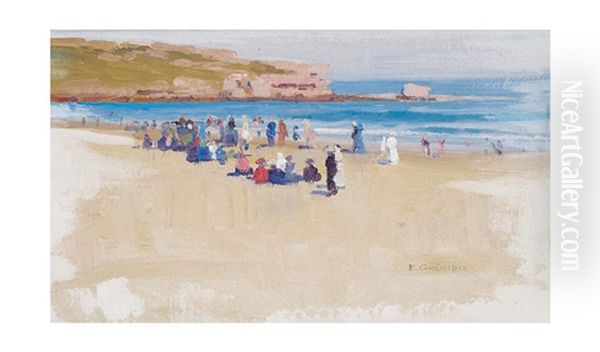

While primarily known for landscapes, Gruner also occasionally painted figure subjects. Works like "The Manly" and "Bondi Beach" depict figures within a landscape setting, often focusing on decorative qualities and colour arrangements. However, these remain secondary to his main achievement in pure landscape painting. He also experimented briefly with printmaking, producing a small number of drypoints, but oil painting remained his primary medium. His dedication to landscape, particularly the pastoral landscapes of New South Wales, defined his artistic output.

European Interlude and Broadening Horizons

In 1923, supported by funds from the Society of Artists and appreciative patrons like the collector R.D. Elliott, Gruner embarked on a significant trip to Europe, remaining abroad for two years. This was a crucial period for broadening his artistic horizons and exposing him directly to the masterpieces of European art, both historical and contemporary. He spent time in London, Paris, and likely travelled elsewhere, visiting major galleries and observing the European landscape firsthand.

In London, he exhibited at the Royal Academy, and in Paris, at the Société des Artistes Français (the Salon). This exposure to the European art scene allowed him to see works by the Impressionists and Post-Impressionists whose principles regarding light and colour had indirectly influenced his own development through teachers like Ashton. Seeing works by artists such as Claude Monet, Camille Pissarro, or Alfred Sisley in person likely reinforced his own commitment to capturing transient light effects, although his style retained its distinctly Australian character and meticulous finish. He may also have studied the light effects in the works of earlier masters like J.M.W. Turner.

While the trip provided valuable experience and exposure, it did not fundamentally alter Gruner's core artistic vision. Upon his return to Australia in 1925, he resumed painting the landscapes he knew best, perhaps with a refreshed perspective but still deeply committed to his established methods and themes. The European interlude confirmed his path rather than diverting it, solidifying his focus on the unique light and atmosphere of his adopted country. Some critics noted a potential broadening of his palette or technique upon his return, but his fundamental approach remained consistent.

Later Career and Evolving Vision

Returning to Australia in 1925, Gruner continued to be a dominant force in landscape painting. He travelled more widely within Australia, seeking new subjects. He painted in the Canberra region, capturing the distinctive landscapes around the developing national capital, as seen in his later Wynne-winning works like "Murrumbidgee Ranges, Canberra" (1934) and "Weetangera, Canberra" (1937). He also undertook painting trips to Victoria and Western Australia, expanding his repertoire of Australian scenes.

However, the Australian art world was beginning to change. The late 1920s and 1930s saw the rise of Modernism, with artists like Margaret Preston, Grace Cossington Smith, and Roy de Maistre exploring new approaches to form, colour, and subject matter, often influenced by Post-Impressionism, Fauvism, and Cubism. In this context, Gruner's meticulous realism and focus on traditional landscape subjects began to appear more conservative to some critics and younger artists.

Despite the shifting artistic tides, Gruner remained committed to his own vision. He continued to refine his technique, seeking ever greater subtlety in his depiction of light and atmosphere. His later works often possess a quiet intensity and a deep connection to the land. While perhaps less groundbreaking than the emerging modernist styles, his paintings retained their popularity with the public and many critics, who valued his technical mastery and his evocative portrayal of familiar Australian scenes. He was sometimes referred to, perhaps slightly critically by modernists but admiringly by others, as "the last of the Australian Impressionists," acknowledging his lineage while hinting at his position relative to newer trends.

His dedication to his craft remained unwavering, even as he began to face personal challenges. He continued to exhibit regularly, and his work was sought after by collectors and public institutions. His influence extended through his teaching, although he did not maintain a formal school for long periods, his example and mentorship were significant for artists who valued traditional skills and sensitivity to nature.

Mentorship and Connections

Elioth Gruner's artistic journey was significantly shaped by his mentors, particularly Julian Ashton and George W. Lambert. Ashton provided his foundational training and early encouragement, instilling the importance of drawing and plein-air painting. Lambert, a highly respected figure painter and portraitist who returned to Australia in 1921 after years abroad, also became an influential teacher and advisor to Gruner, particularly regarding composition and form. Lambert's emphasis on strong draughtsmanship likely resonated with Gruner's own meticulous approach.

Gruner, in turn, became a respected figure within the Sydney art community. He maintained connections with fellow artists and patrons. His relationship with collectors like R.D. Elliott and figures associated with the art establishment, such as the architect and trustee B.J. Waterhouse, indicates his standing. While perhaps not known for forming close collaborative partnerships in the manner of some earlier artists, he was part of the fabric of the Sydney Society of Artists and exhibited alongside contemporaries.

His contemporaries included not only the established figures like Ashton and Lambert, or landscape painters like Hans Heysen, but also artists exploring different paths. Figures like Sydney Long, known for his Art Nouveau-influenced decorative landscapes, or the watercolourist J.J. Hilder, represented different facets of the art scene during Gruner's active years. While Gruner pursued his own distinct path focused on light and realism, he operated within this broader artistic milieu, participating in exhibitions and contributing to the artistic discourse of the time through his work and his consistent presence.

His influence can be seen less in direct stylistic imitation by later artists and more in the enduring benchmark he set for technical excellence and sensitivity in Australian landscape painting. His dedication to capturing the specific qualities of Australian light provided a touchstone for subsequent generations, even those who moved in different stylistic directions.

Challenges and Final Years

Despite his immense professional success, Elioth Gruner's later life was marked by significant personal struggles. He suffered from chronic health problems, including nephritis. More debilitatingly, he battled severe depression and alcoholism, particularly in his final years. These issues undoubtedly impacted his well-being and potentially his artistic output, although he continued to paint and exhibit.

His intense self-criticism, noted even earlier in his career, perhaps intensified with his personal difficulties. There are accounts, mentioned in biographical sources, of Gruner destroying works that he felt did not meet his own exacting standards. This act speaks volumes about his perfectionism and perhaps the inner turmoil he experienced. It suggests an artist constantly striving for an ideal representation, deeply sensitive to perceived flaws in his own creations.

His health continued to decline, and on October 17, 1939, Elioth Gruner died in his home in Waverley, Sydney, at the relatively young age of 56. His death marked the end of a significant chapter in Australian art. He left behind a legacy defined by luminous landscapes and an unwavering dedication to capturing the beauty he observed in nature.

Legacy and Historical Position

Elioth Gruner occupies a secure and respected place in the history of Australian art. He is remembered primarily as a master of landscape painting, renowned for his unparalleled ability to capture the subtle effects of Australian light and atmosphere. His work bridges the gap between the nationalistic narratives of the late Heidelberg School and the emerging modernism of the mid-twentieth century. While stylistically rooted in tonal realism and influenced by Impressionist principles of light, his meticulous technique and poetic sensibility were uniquely his own.

His seven Wynne Prize wins remain a testament to his dominance and critical acclaim during his lifetime. Works like "Spring Frost" and "Morning Light" are considered iconic images in Australian art history, beloved by the public and studied by art students. His paintings are held in all major Australian public collections, including the National Gallery of Australia, the Art Gallery of New South Wales, the National Gallery of Victoria, and numerous regional galleries, ensuring his work remains accessible.

While later overshadowed by the rise of Modernism, Gruner's contribution remains significant. He represented the culmination of a particular tradition of landscape painting focused on naturalistic representation, technical refinement, and sensitivity to place. His dedication to plein-air painting and his profound understanding of light continue to inspire admiration. He captured a specific vision of the Australian landscape – often pastoral, serene, and bathed in a gentle, lyrical light – that resonated deeply with the sensibilities of his time and continues to evoke a sense of timeless beauty. Elioth Gruner's legacy is that of an artist who saw and rendered the light of Australia with exceptional clarity and devotion.