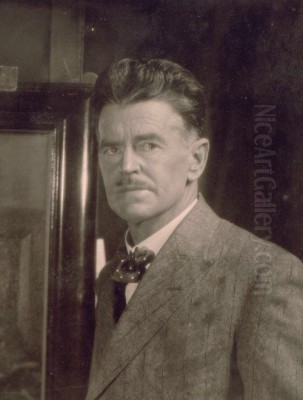

William Beckwith McInnes stands as a pivotal figure in the narrative of early twentieth-century Australian art. Renowned primarily as a portraitist of exceptional skill and sensitivity, he also produced evocative landscapes that captured the unique Australian light. His seven victories in the prestigious Archibald Prize remain a record, underscoring his dominance in the field of portraiture during his era. Beyond his prolific output, McInnes played a crucial role as an educator, shaping a generation of artists as the Head of the National Gallery of Victoria Art School. His career, though relatively short, left an indelible mark on the nation's artistic landscape, balancing traditional academicism with an openness to modern currents.

Early Life and Artistic Awakening

Born in St Kilda, a suburb of Melbourne, in 1889, William Beckwith McInnes, often known as W.B. McInnes, demonstrated an early proclivity for art. This nascent talent was nurtured, and by the tender age of 14, he was enrolled at the National Gallery of Victoria Art School. This institution was the crucible of Australian art at the time, and McInnes was fortunate to study under two of its most influential figures: Frederick McCubbin and Lindsay Bernard Hall.

McCubbin, a leading member of the Heidelberg School, which included luminaries like Tom Roberts and Arthur Streeton, would have instilled in McInnes a deep appreciation for the Australian landscape and the impressionistic rendering of light and atmosphere. Bernard Hall, on the other hand, was a more academically inclined painter and a long-serving director of the National Gallery of Victoria. From Hall, McInnes would have received rigorous training in draftsmanship, composition, and the classical traditions of European art. This dual influence—the nationalistic focus of the Heidelberg School and the academic discipline of Hall—would prove foundational to McInnes's artistic development. His academic abilities were quickly recognized, setting him apart even in a talented cohort.

Formative Years and Early Challenges

During his time at the National Gallery School, McInnes honed his skills, particularly in figure drawing and portraiture. He absorbed the lessons of his mentors, developing a keen eye for likeness and character. However, the path of an aspiring artist is seldom without its hurdles. A notable incident occurred in 1907 when McInnes submitted a portrait for assessment. While the work was considered by many to be of high quality, the judging panel failed to accord it the recognition he, and others, felt it deserved. Such experiences, while disheartening, often serve to strengthen an artist's resolve, and McInnes continued to pursue his craft with dedication.

The artistic environment in Melbourne at this time was vibrant, with ongoing discussions about the direction of Australian art. Artists like John Longstaff, another accomplished portraitist and multiple Archibald Prize winner, were established figures, while a new generation was beginning to make its mark. McInnes was part of this emerging wave, eager to absorb influences both local and international.

The European Sojourn: Broadening Horizons

In 1911, like many ambitious Australian artists of his generation, McInnes embarked on a journey to Europe to further his studies and immerse himself in the masterpieces of Western art. This was a self-funded endeavor, indicating his commitment to his artistic growth. His travels between 1911 and 1913 took him through France, Spain, Morocco, and Great Britain. This period was crucial for McInnes, exposing him to a wider range of artistic styles and techniques.

In the great galleries of Europe, he studied the works of Old Masters who would profoundly influence his portraiture, including the psychological depth of Rembrandt, the regal elegance of Velázquez, the dynamic compositions of Peter Paul Rubens, and the sophisticated character studies of Scottish portraitist Sir Henry Raeburn. He also engaged with contemporary art movements and interacted with fellow artists, including figures noted as Ramsden and Reynolds (likely referring to contemporary British artists rather than solely the historical Sir Joshua Reynolds, though the latter's influence on academic portraiture was pervasive). During his time abroad, McInnes was not merely a student; he was also a practicing artist, creating numerous landscape paintings that reflected his experiences in diverse locales. His European sojourn culminated in the exhibition of his work at the prestigious Royal Academy in London in 1913, and he also held a solo exhibition at the Athenaeum Gallery, signaling his growing reputation.

Return to Australia and Ascendancy in the Art World

McInnes returned to Australia in 1913, his artistic vision enriched and his technical skills further refined. He quickly began to establish himself as a significant presence in the Australian art scene. His European experiences had equipped him with a sophisticated understanding of painterly traditions, which he adeptly applied to Australian subjects.

In 1916, a significant year for McInnes, he was appointed acting principal of the National Gallery of Victoria Art School, stepping into a teaching role at his alma mater. Later that same year, following the death of his former mentor Frederick McCubbin, McInnes was appointed the permanent Head of the School, a position he would hold with distinction until 1934. This appointment was a testament to his recognized skill and his standing within the artistic community. Also in 1916, McInnes won the Wynne Prize for landscape painting, an award that further solidified his reputation. He was increasingly seen by some as an heir to the landscape tradition of Arthur Streeton, particularly admired for his ability to capture the brilliant effects of Australian sunlight.

Master of Portraiture: The Archibald Dominance

While a capable landscape painter, it was in portraiture that William Beckwith McInnes truly excelled and achieved lasting fame. He became one of Australia's most sought-after portraitists, known for his ability to capture not only a physical likeness but also the character and presence of his sitters. His style was often described as academic and tonally realist, demonstrating a masterful command of traditional techniques.

His preeminence in this field was most visibly demonstrated by his remarkable success in the Archibald Prize, Australia's foremost award for portraiture. McInnes won the prize an unprecedented seven times: in 1921 (for his portrait of architect Desbrowe Annear), 1922 (H. Desbrowe Annear, Esq.), 1923 (Portrait of a Lady), 1924 (Miss Collins), 1926 (Silk and Lace – Miss Esther Paterson), 1930 (Drum-Major Harry McClelland), and 1936 (Dr. Julian Smith). This record remains unbroken and highlights the consistent quality and appeal of his work to the trustees of the Art Gallery of New South Wales, who award the prize. His sitters often included prominent figures from various walks of life, from fellow artists and society figures to leaders in business and politics. His competitors for the Archibald often included distinguished artists such as John Longstaff and George Washington Lambert, making his repeated victories all the more impressive.

Official Commissions and Notable Portraits

McInnes's reputation as a leading portraitist led to numerous official commissions. He was entrusted with painting portraits of war heroes, prime ministers, governors, and even British royalty. These commissions were not merely artistic endeavors but also important historical records, capturing the likenesses of individuals who shaped the nation.

In 1927, he was commissioned to paint a depiction of the opening of the provisional Parliament House in Canberra by the Duke of York (later King George VI). This was a significant national event, and McInnes's selection for this task underscored his status. Later, in 1933, he travelled to London specifically to paint a portrait of the Duke of York. Another notable work is his sensitive portrait of the beloved stage actress Nellie Stewart, which was acquired by the National Gallery of Victoria, further cementing his place in public collections. These official portraits required a blend of technical skill, an ability to convey dignity and authority, and a sensitivity to the sitter's personality, qualities McInnes possessed in abundance. His approach often drew comparisons to the grand manner of British portraitists like Sir Thomas Lawrence, though adapted to a more modern sensibility.

Landscapes: Capturing the Australian Light and Atmosphere

Alongside his prolific portraiture practice, McInnes continued to paint landscapes throughout his career. His early training under McCubbin had instilled a love for the Australian bush, and his European travels had broadened his understanding of landscape painting techniques. His landscapes are characterized by their subtle tonal harmonies, their adept rendering of light and shadow, and their ability to evoke a distinct sense of place.

His Wynne Prize-winning work of 1916 was a landscape, and he produced many other fine examples throughout his career. One notable landscape, "Moonrise" (1915), showcases his skill in capturing the ethereal effects of light in the Australian environment. While perhaps not as overtly impressionistic as some of his Heidelberg School predecessors like Charles Conder or Tom Roberts, McInnes's landscapes possess a quiet lyricism and a deep appreciation for the nuances of the natural world. He often painted en plein air, directly observing his subjects, but brought a studio painter's discipline to the final composition and finish. His landscapes were exhibited regularly and found favor with collectors and critics alike, complementing his reputation as a portraitist.

A Leader in Art Education: The National Gallery School Directorship

McInnes's contribution to Australian art extended significantly beyond his own canvases. As Head of the National Gallery of Victoria Art School from 1916 to 1934, he played a vital role in shaping the next generation of Australian artists. He succeeded his mentor, Frederick McCubbin, and continued the school's tradition of providing rigorous academic training.

During his tenure, McInnes was known for his commitment to teaching the fundamentals of drawing, painting, and composition. He believed in a strong grounding in traditional skills, even as he acknowledged the evolving landscape of modern art. He was reportedly a dedicated and inspiring teacher, encouraging his students while maintaining high standards. Under his leadership, the NGV School continued to be a preeminent institution for art education in Australia. Many artists who would go on to achieve prominence passed through its doors during these years, benefiting from his guidance and the school's curriculum. His educational philosophy aimed to equip students with the technical mastery necessary to express their own artistic visions, whether they pursued traditional or more contemporary paths. Artists like William Dargie, who himself became an eight-time Archibald winner, would have been aware of McInnes's towering presence in the portraiture field and his educational legacy.

Personal Life and Artistic Milieu

In 11915, William Beckwith McInnes married fellow artist Violet Muriel Musgrove. Violet was a talented artist in her own right, and their partnership was one of mutual support within the artistic sphere. The couple had six children, and they established their family home in Alphington, a suburb of Melbourne. Their home was described as having a pastoral quality, and this environment likely provided a supportive backdrop for McInnes's demanding career as both a painter and an educator.

The artistic community in Melbourne during this period was relatively close-knit. McInnes would have interacted with many of the leading artists of the day, including those he taught, those he exhibited alongside, and those whose work he admired or competed against. His life was deeply enmeshed in the rhythms of the art world – the studio, the art school, exhibition openings, and the ongoing discourse about art's role and direction in Australia. His wife, Violet, continued her artistic pursuits, and their shared passion for art undoubtedly enriched their family life.

Style, Modernism, and Artistic Debates

McInnes's artistic style is generally characterized by its academic realism, particularly in his portraiture. He possessed a superb technical command, evident in his draftsmanship, his handling of paint, and his understanding of anatomy and form. His portraits are often imbued with a sense of dignity and psychological insight, rendered with a smooth, refined finish.

While firmly rooted in traditional techniques, McInnes was not entirely immune to the currents of modernism that were beginning to influence Australian art. The provided information suggests he was an advocate for modernism, though this likely referred to a more moderate, evolutionary form rather than the radical avant-garde movements emerging in Europe. In the Australian context of the 1920s and 1930s, "modernism" could encompass a range of departures from strict academicism, including brighter palettes, simplified forms, and a greater emphasis on decorative qualities. Artists like Grace Cossington Smith, Margaret Preston, and Roy de Maistre were exploring more overtly modernist styles. McInnes's modernism might be seen in his willingness to experiment with composition and his fresh, direct approach to capturing light, particularly in his landscapes.

However, the interwar period in Australian art was marked by vigorous debates between traditionalists and modernists. McInnes, with his strong academic grounding and popular success in established genres, sometimes found himself in a position that could be perceived as conservative by more radical modernists. Nevertheless, his role as an educator required him to engage with new ideas, and he aimed to provide students with a solid foundation from which they could explore various artistic paths. His own work, while not revolutionary, represented a high point of academic achievement in Australian art.

Untimely Death and Enduring Influence

William Beckwith McInnes's highly productive and influential career was cut tragically short. He passed away from heart disease in 1939 at the age of just 50. His death was a significant loss to the Australian art world, depriving it of one of its most accomplished portraitists and respected educators.

Despite his relatively brief life, McInnes left an enduring legacy. His portraits hang in major public collections across Australia, including the National Gallery of Victoria, the Art Gallery of New South Wales, and the National Gallery of Australia. They serve as important historical documents and as exemplars of early twentieth-century Australian portraiture. His record seven Archibald Prize wins remain a benchmark, testifying to his mastery of the genre.

His influence also extended through his many students at the National Gallery School, who carried forward aspects of his teaching and contributed to the ongoing development of Australian art. He helped to maintain a high standard of technical proficiency in a period of artistic transition and debate. While artistic styles have evolved considerably since his time, McInnes's dedication to craftsmanship, his sensitive portrayal of character, and his ability to capture the essence of the Australian scene ensure his continued relevance and appreciation. He remains a key figure for understanding the trajectory of Australian art in the first half of the twentieth century, a bridge between the nationalist romanticism of the Heidelberg School and the emerging complexities of modern Australian art. His work continues to be studied and admired for its skill, its integrity, and its contribution to the nation's cultural heritage.