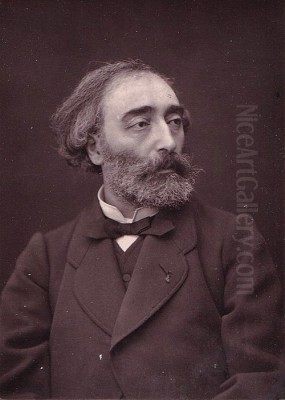

Émile Lévy (1826-1890) stands as a significant, if sometimes overlooked, figure in the landscape of 19th-century French art. A product of the rigorous academic tradition, Lévy carved out a distinguished career, excelling in genre scenes, historical narratives, and particularly, portraiture. His life and work offer a valuable window into the artistic currents, institutional structures, and prevailing tastes of an era that witnessed both the zenith of academic art and the burgeoning of revolutionary avant-garde movements. This exploration delves into Lévy's biography, his artistic training, his stylistic evolution, his major works, and his place within the vibrant, competitive art world of Paris.

Early Life and Artistic Formation in Paris

Born in Paris on August 29, 1826, Émile Lévy emerged into a city that was the undisputed cultural capital of Europe. The artistic environment of Paris during his formative years was rich and dynamic, still heavily influenced by the Neoclassical ideals passed down from Jacques-Louis David, yet also stirring with the passions of Romanticism, exemplified by artists like Eugène Delacroix and Théodore Géricault. It was within this stimulating milieu that Lévy's artistic inclinations began to take shape.

Recognizing his talent, Lévy pursued formal artistic training, a prerequisite for any aspiring painter aiming for official recognition and success. He enrolled in the prestigious École des Beaux-Arts in Paris, the cornerstone of academic art education in France. The École's curriculum was famously demanding, emphasizing mastery of drawing, anatomy, perspective, and the study of classical antiquity and Renaissance masters. Students spent countless hours drawing from plaster casts of ancient sculptures before progressing to life drawing.

At the École, Lévy had the privilege of studying under two notable academic painters: François-Édouard Picot (1786-1868) and Abel de Pujol (1785-1861). Both Picot and Pujol were themselves products of the Neoclassical tradition, having been pupils of Jacques-Louis David or his close followers. Picot was known for his historical and mythological paintings, as well as portraits, and was a respected teacher. Abel de Pujol, similarly, specialized in religious and historical subjects, contributing to the decoration of numerous public buildings and churches. Under their tutelage, Lévy would have imbibed the core tenets of academic art: clarity of form, idealized figures, balanced compositions, and often, a didactic or moralizing subject matter. This foundational training was crucial in shaping his technical proficiency and artistic outlook.

The Coveted Prix de Rome and Italian Sojourn

A pivotal moment in the career of any ambitious young artist at the École des Beaux-Arts was the competition for the Prix de Rome. This highly prestigious scholarship, awarded annually, granted the winner a period of study at the French Academy in Rome, housed in the magnificent Villa Medici. For Lévy, this aspiration became a reality in 1854 when he won the Grand Prix de Rome in painting. This achievement was not merely an honor; it was a significant career catalyst, providing him with the opportunity to immerse himself in the art of classical antiquity and the Italian Renaissance masters firsthand.

The years spent in Italy, typically three to five, were transformative for Prix de Rome laureates. They were expected to study and copy the works of Raphael, Michelangelo, Titian, and others, as well as ancient Roman art, and to send back regular dispatches of their work (known as "envois de Rome") to Paris as proof of their progress. This period allowed Lévy to refine his technique, broaden his historical and iconographic knowledge, and absorb the light and atmosphere of Italy, which often subtly influenced the palettes of Northern European artists. His time in Italy, from roughly 1855 to 1857/59, solidified his classical grounding and prepared him for a successful career upon his return to Paris.

Establishing a Career: The Paris Salon and Official Recognition

Upon returning to Paris, Émile Lévy set about establishing himself as a professional artist. The primary avenue for exhibition and recognition was the official Paris Salon, an annual (or biennial) juried exhibition organized by the Académie des Beaux-Arts. Success at the Salon could lead to critical acclaim, state purchases, private commissions, and further honors. Lévy became a regular exhibitor at the Salon, and his works began to attract positive attention.

His painting, Noah Cursing Canaan (also known as The Malediction of Ham or Noé maudissant Canaan), completed in 1855, likely during his early time in Rome or shortly thereafter, was an early example of his engagement with significant biblical themes, a staple of academic history painting. Another important work from this period was The Supper of the Martyrs (or Le Dîner des martyrs) exhibited in 1859, which demonstrated his ability to handle complex multi-figure compositions with dramatic intensity.

Lévy's dedication and skill did not go unrewarded. He received several medals at the Salons, culminating in a first-class medal in 1878, a significant acknowledgment of his standing in the artistic community. Furthermore, in 1867, he was made a Chevalier of the Legion of Honour (Légion d'honneur), one of France's highest civilian decorations, underscoring his official recognition and success. These accolades cemented his reputation as a respected academic painter. He settled permanently in Paris, where he focused increasingly on portraiture alongside his historical and genre subjects.

Artistic Style: Adherence to Academic Principles

Émile Lévy's artistic style remained firmly rooted in the French academic tradition throughout his career. This tradition, often referred to broadly as Academicism, prioritized meticulous draftsmanship, a smooth, polished finish (the "fini"), idealized human forms, and compositions based on classical or Renaissance models. Subject matter was often drawn from history, mythology, religion, or allegory, frequently imbued with a moral or didactic purpose.

Lévy's work embodies these characteristics. His figures are typically well-drawn and gracefully posed, often with a sense of classical poise. His compositions are carefully structured, aiming for balance and clarity. He was praised for his delicate and harmonious use of color and his ability to render textures, particularly fabrics, with convincing realism. While his themes could be dramatic, such as in The Death of Orpheus, the emotional expression was generally restrained and idealized, in keeping with academic decorum.

It is important to note that Lévy's adherence to academic principles meant that he largely eschewed the "radical features" of emerging movements like Realism, championed by Gustave Courbet, which focused on unidealized depictions of contemporary life and ordinary people. Nor did he embrace the Impressionists' revolutionary approach to light, color, and brushwork that began to gain traction in the 1870s with artists like Claude Monet, Camille Pissarro, and Pierre-Auguste Renoir. Lévy remained committed to the established aesthetic values of the Academy, which, while ensuring him official success, also placed him in a category of artists whose reputations would later be overshadowed by the avant-garde.

Masterpieces and Major Works

Several key works define Émile Lévy's oeuvre and showcase his talents across different genres.

The Death of Orpheus (1866): Perhaps his most famous painting, La Mort d'Orphée is now housed in the Musée d'Orsay (though often cited as Louvre, it was transferred). This dramatic work depicts the mythological poet Orpheus being torn apart by the enraged Maenads (Bacchantes). The composition is dynamic, with the frenzied, semi-nude figures of the Maenads contrasting with the tragic figure of Orpheus. Lévy's skill in rendering the human form, both male and female, is evident, as is his ability to create a scene of high drama while maintaining a degree of classical restraint. The painting was exhibited at the Salon of 1866 and was acquired by the state, a mark of its success. It is a quintessential example of academic history painting drawing on classical mythology.

Noah Cursing Canaan (1855): This early work tackles a powerful Old Testament subject. The scene typically depicts a venerable Noah, angered by his son Ham's disrespect, pronouncing a curse upon Ham's son Canaan. Such subjects allowed artists to explore themes of patriarchal authority, divine justice, and human failing, all within a grand historical framework. Lévy's treatment would have emphasized clear narrative and expressive, yet dignified, figures.

The Supper of the Martyrs (1859): This painting likely depicted early Christians sharing a meal, possibly the Eucharist, under threat of persecution. Religious themes were highly valued in academic art, and this subject would have allowed Lévy to explore piety, courage, and communal faith, often with an emphasis on serene devotion in the face of adversity, a common trope in 19th-century religious painting.

Love and Folly (L'Amour et la Folie, 1874): Allegorical subjects were also popular, allowing for imaginative compositions and the personification of abstract concepts. Love and Folly likely depicted Cupid (Love) interacting with Folly, a theme that had been explored by artists since the Renaissance, often with playful or moralizing undertones. Lévy's interpretation would have featured graceful, idealized figures in a harmonious composition.

Infancy (L'Enfance, 1885): This title suggests a genre scene, perhaps an idealized depiction of childhood, or a more allegorical representation of the early stages of life. Such works often appealed to sentimental tastes prevalent in the 19th century.

The Assumption (1885): A major religious commission or Salon piece, The Assumption would depict the Virgin Mary being taken up into heaven. This was a traditional and highly revered subject, offering scope for a grand, uplifting composition with celestial figures and a sense of spiritual transcendence. Its exhibition in the French government's cabinet salon indicates its importance.

Lévy as a Portraitist

While accomplished in historical and mythological subjects, Émile Lévy also gained considerable renown as a portrait painter. In the 19th century, portraiture was a lucrative and highly sought-after genre, with artists like Léon Bonnat and Carolus-Duran achieving great fame and fortune. Lévy's portraits were characterized by their elegance, refined execution, and often, a sensitive psychological insight into the sitter.

A notable example is his Portrait of Madame José-Maria de Heredia (1885). José-Maria de Heredia was a prominent Parnassian poet, and his wife would have been a figure in Parisian literary and social circles. Lévy's portrait of her, reportedly executed in pastels, showcased his versatility in different media. Pastel allowed for a softness and luminosity that could be particularly flattering for female sitters. Academic portraiture aimed not just for a likeness, but also to convey the social standing and character of the individual, often through pose, attire, and setting. Lévy excelled in this, creating portraits that were both accurate representations and aesthetically pleasing works of art. His skill in this area ensured a steady stream of commissions from the Parisian elite.

The Context of the French Academic System and Contemporaries

To fully appreciate Émile Lévy's career, it is essential to understand the French academic system that shaped it. The École des Beaux-Arts, the Prix de Rome, and the Paris Salon formed an interconnected structure that dominated the art world for much of the 19th century. This system, while providing rigorous training and opportunities for recognition, was also criticized for its conservatism and resistance to innovation.

Lévy was a contemporary of many other highly successful academic painters who navigated this system, including:

Jean-Léon Gérôme (1824-1904): Famous for his highly detailed Orientalist scenes and historical subjects.

Alexandre Cabanel (1823-1889): Known for mythological and historical paintings like The Birth of Venus, a quintessential Salon success.

William-Adolphe Bouguereau (1825-1905): Immensely popular for his idealized depictions of mythological figures, peasants, and nudes, characterized by flawless technique.

Ernest Meissonier (1815-1891): Renowned for his meticulously detailed small-scale historical and military scenes.

Paul Baudry (1828-1886): Celebrated for his decorative cycles, most notably for the Paris Opéra.

Léon Bonnat (1833-1922): A leading portrait painter and influential teacher.

Jean-Auguste-Dominique Ingres (1780-1867): While of an earlier generation, Ingres was a towering figure whose Neoclassical ideals and emphasis on line profoundly influenced the Academy throughout Lévy's lifetime. His rivalry with the Romantic Delacroix defined much of the artistic debate in the first half of the century.

These artists, like Lévy, generally adhered to the hierarchy of genres, which placed history painting (including mythological, religious, and allegorical subjects) at the apex, followed by portraiture, genre painting, landscape, and still life. Lévy's focus on history painting and portraiture aligned perfectly with these established values.

However, this was also an era of significant artistic ferment. The Barbizon School painters, such as Jean-François Millet and Théodore Rousseau, had already challenged academic conventions with their realistic and poetic depictions of rural life and landscape. Gustave Courbet's Realist movement directly confronted academic idealism. And from the 1860s and 1870s onwards, Édouard Manet, followed by the Impressionists (Claude Monet, Edgar Degas, Camille Pissarro, Berthe Morisot, Alfred Sisley, Pierre-Auguste Renoir), launched a more radical assault on academic norms, leading to the Salon des Refusés in 1863 and their own independent exhibitions.

Lévy and his academic colleagues represented the established order, often serving on Salon juries or teaching at the École, and their work was generally favored by state patronage and the bourgeois public. While their art was later denigrated by proponents of modernism, recent art historical scholarship has sought a more balanced view, recognizing the technical skill and cultural significance of academic painting.

Challenges, Critical Reception, and Later Career

While Émile Lévy achieved considerable success within the academic system, his career was not without the challenges inherent in the competitive Parisian art world. Gaining entry to the Salon, securing good placement for one's works, and attracting favorable critical reviews were ongoing concerns for all artists. The rise of avant-garde movements also began to shift critical attention and, eventually, public taste, although academic art retained its prestige for many decades.

The provided information hints at potential challenges, such as his works not always receiving "wide recognition" despite awards, or a possible decline in output in his later years. This is not uncommon; artistic careers can have ebbs and flows, and critical fortunes can change. However, his consistent Salon presence, the awards he received, and his prestigious Legion of Honour medal indicate a career that was, by most measures, highly successful within his chosen field.

His works were generally well-received by conservative critics who valued technical skill, adherence to classical principles, and elevated subject matter. Critics like Théophile Gautier, a champion of "art for art's sake" but also an admirer of polished technique, might have appreciated aspects of Lévy's work. Conversely, critics more aligned with the avant-garde, such as Émile Zola (a defender of Manet and the early Impressionists) or later, Félix Fénéon (a champion of Neo-Impressionism), would likely have found Lévy's art conventional.

Lévy continued to paint and exhibit throughout his life. He passed away in Paris on August 4, 1890. By the time of his death, the art world was already undergoing profound transformations, with Post-Impressionist artists like Vincent van Gogh, Paul Gauguin, and Georges Seurat pushing the boundaries of artistic expression even further.

Legacy and Conclusion

Émile Lévy's legacy is primarily that of a skilled and respected representative of 19th-century French Academicism. His paintings, particularly works like The Death of Orpheus, remain important examples of the mythological and historical subjects favored by the Academy. His portraits captured the likenesses and status of Parisian society figures with elegance and technical finesse.

While his name may not be as widely recognized today as those of his Impressionist contemporaries or even some of the more flamboyant academic figures like Gérôme or Bouguereau, Lévy's contributions are significant for understanding the mainstream artistic production of his time. His career illustrates the path to success within the established institutional framework of the École des Beaux-Arts and the Paris Salon. His adherence to Neoclassical norms, his refined technique, and his choice of elevated themes place him firmly within the tradition of artists who sought to uphold the grand ideals of beauty, order, and moral instruction in art.

In recent decades, art history has moved towards a more inclusive understanding of the 19th century, re-evaluating academic artists who were long overshadowed by the modernist narrative. In this context, Émile Lévy's work merits continued study, not only for its intrinsic artistic qualities – the delicacy of his color, the grace of his figures, and the drama of his compositions – but also for what it reveals about the complex, multifaceted art world of 19th-century Paris, an era of both enduring tradition and radical change. His paintings serve as a testament to a particular vision of art that, for a significant period, defined official taste and artistic aspiration in France and beyond.