Jean-Victor Bertin stands as a pivotal figure in the evolution of French landscape painting. Born in Paris in 1767 and passing away in the same city in 1842, his life spanned a period of immense social and artistic transformation in France. Bertin carved a distinct niche for himself as a leading exponent of the Neoclassical landscape, a genre he helped to define and elevate during his long and productive career.

Primarily known as a painter, Bertin was also proficient in lithography, using the medium to disseminate studies of nature. His artistic journey began within the established academic system, but his vision extended beyond mere imitation, seeking to blend the idealized traditions of the past with a fresh, albeit controlled, observation of the natural world. He became not only a celebrated artist in his own right but also an influential teacher whose legacy shaped the course of landscape painting in the 19th century.

Early Life and Artistic Formation

Jean-Victor Bertin's formal artistic education commenced in 1785 when he entered the prestigious Académie Royale de Peinture et de Sculpture in Paris. His initial training was under the guidance of Gabriel-François Doyen, a respected history painter. This grounding in history painting, the most esteemed genre within the academic hierarchy, likely provided Bertin with a strong foundation in composition and figural representation, elements that would subtly inform his later landscape work.

However, a decisive shift in his artistic direction occurred around 1788 when he began studying under Pierre-Henri de Valenciennes. Valenciennes was a crucial figure in the development of Neoclassical landscape painting in France. He championed a return to the principles of classical order and idealized beauty, drawing inspiration from 17th-century masters, while simultaneously advocating for the importance of direct study from nature through outdoor sketching.

Under Valenciennes' tutelage, Bertin absorbed the tenets of the idealized landscape. This approach sought not a literal transcription of a specific view, but rather a harmonious composition evoking classical serenity and grandeur. Valenciennes' emphasis on structure, clarity, and the integration of classical elements profoundly shaped Bertin's developing style and set the course for his future specialization in landscape.

The Neoclassical Landscape Ideal

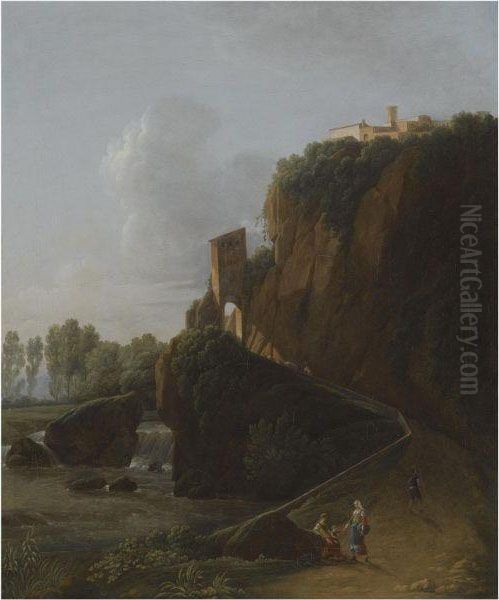

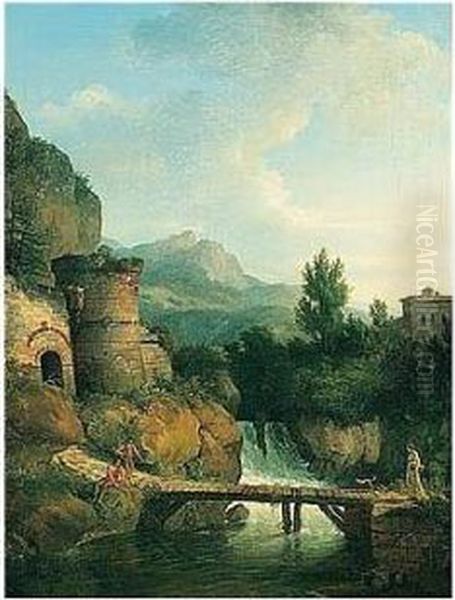

Bertin's art is synonymous with the Neoclassical landscape. This style, flourishing in the late 18th and early 19th centuries, reacted against the perceived frivolity of the preceding Rococo period, seeking inspiration in the art and values of classical antiquity. In landscape painting, this translated into ordered, balanced compositions, clear delineation of forms, and a preference for serene, often Italianate, scenery.

Deeply influenced by the 17th-century masters Nicolas Poussin and Claude Lorrain, Bertin adopted their structured approach and idealized vision. From Poussin, he inherited a sense of rigorous composition, often incorporating architectural elements or mythological figures that lent historical or allegorical weight to the scene. From Claude, he learned to master atmospheric effects and the depiction of golden, tranquil light bathing idealized pastoral settings.

Bertin's landscapes are rarely wild or untamed. Instead, they present a vision of nature perfected and harmonized by classical principles. Trees are often carefully arranged to frame vistas, rivers flow gently, and skies are typically calm. Small figures, sometimes drawn from mythology or ancient history, might populate the scene, reinforcing the classical mood and adding narrative interest. This approach aligned perfectly with the Neoclassical emphasis on reason, order, and timeless beauty.

The Concept of Historical Landscape

Bertin, alongside his mentor Valenciennes, was instrumental in promoting the genre known as "paysage historique" or historical landscape. This was a specific type of idealized landscape painting that aimed to elevate the genre's status within the rigid academic hierarchy, which traditionally placed history painting at the apex.

Historical landscapes were not merely depictions of scenery; they were intended to serve as appropriate settings for significant historical, mythological, or biblical narratives. The landscape itself, while idealized and classically composed, needed to possess a certain nobility and grandeur suitable for these elevated themes. The careful arrangement of natural elements, the inclusion of classical architecture (often ruins), and the overall sense of timelessness were key characteristics.

Bertin's dedication to this genre reflected a desire to prove that landscape painting could possess the same intellectual and moral weight as history painting. His works often featured titles explicitly referencing classical myths, such as Forest with Apollo and Daphne, demonstrating this ambition. The success of Bertin and Valenciennes in advocating for this genre contributed significantly to the growing appreciation and eventual academic recognition of landscape painting in France.

Direct Observation and Studio Practice

While deeply rooted in the classical tradition, Bertin's approach was not solely based on imitating past masters or adhering to rigid formulas. Following the precepts of his teacher Valenciennes, Bertin understood the importance of studying nature directly. He engaged in the practice of creating études – small-scale studies, often painted in oil on paper outdoors (en plein air) – to capture specific effects of light, topography, and foliage.

These outdoor studies, however, were generally not considered finished works in themselves during this period. They served as source material, a visual library of naturalistic details and atmospheric effects that Bertin would later synthesize and incorporate into his larger, more formally composed studio paintings. The final canvases were carefully constructed, balancing the information gathered from direct observation with the idealized principles of Neoclassical composition.

This blend of direct study and idealized composition was characteristic of the Valenciennes school. It allowed artists like Bertin to imbue their classical landscapes with a greater sense of naturalism and atmospheric truth than might be found in purely formulaic works, while still maintaining the overall harmony and order demanded by Neoclassical taste. This practice laid groundwork, albeit indirectly, for later movements like the Barbizon School that would place even greater emphasis on direct observation.

Career at the Salon and Official Recognition

Jean-Victor Bertin enjoyed a long and successful public career, marked by consistent participation in the prestigious Paris Salon. He first exhibited his work at the Salon in 1793, during the tumultuous period of the French Revolution, and continued to show his paintings there almost annually until his death in 1842. This regular presence ensured his visibility and cemented his reputation among critics, collectors, and fellow artists.

His meticulously crafted Neoclassical landscapes found favour with the juries and the public. Bertin received numerous accolades throughout his career, reflecting his standing within the artistic establishment. A significant honour came in 1822 when he was awarded the Cross of the Legion of Honour (Chevalier de la Légion d'honneur), a prestigious order established by Napoleon Bonaparte, recognizing his significant contributions to French art.

Beyond his personal success, Bertin played an active role in advocating for the landscape genre. He and Valenciennes lobbied the Institut de France for the creation of a specific Prix de Rome category for historical landscape painting. Their efforts bore fruit in 1817 with the establishment of this prize, a landmark achievement that officially recognized historical landscape as a discipline worthy of the highest academic distinction and provided crucial support for young artists specializing in the genre.

A Prolific Teacher: Shaping the Next Generation

Bertin's influence extended far beyond his own canvases; he was a highly respected and sought-after teacher. He held a professorship at the prestigious École des Beaux-Arts in Paris, the successor institution to the Académie Royale. His studio attracted numerous aspiring artists eager to learn the principles of Neoclassical landscape painting from one of its acknowledged masters.

His teaching methods emphasized the foundational importance of drawing, rigorous composition, and the careful study of light and form, reflecting the academic tradition. He passed on the techniques learned from Valenciennes, including the practice of outdoor sketching combined with idealized studio finishing. He encouraged his students to study the works of Poussin and Claude Lorrain, instilling in them an appreciation for classical structure and harmony.

Bertin's dedication to teaching ensured the continuation and evolution of the Neoclassical landscape tradition. He provided a crucial link between the established masters of the 17th century and the emerging talents of the 19th century, equipping them with the technical skills and aesthetic principles necessary to navigate the changing artistic landscape of their time. His pedagogical influence was profound and long-lasting.

Key Students: Corot and Michallon

Among Bertin's many students, two stand out for their subsequent fame and contributions to landscape painting: Achille-Etna Michallon and Jean-Baptiste-Camille Corot.

Achille-Etna Michallon (1796-1822) was a prodigious talent who, fittingly, became the very first winner of the Prix de Rome for historical landscape in 1817, the prize his teacher Bertin had helped establish. Michallon fully embraced the Neoclassical ideals taught by Bertin and Valenciennes, producing highly finished, classically inspired landscapes during his tragically short career. His early death cut short a promising future, but his success validated the importance of the new prize and the genre itself.

Jean-Baptiste-Camille Corot (1796-1875) studied with Bertin from 1822. Corot initially absorbed Bertin's Neoclassical discipline, evident in the clear structure and precise drawing of his early works, particularly those painted during his first trip to Italy. Corot learned the importance of compositional structure and tonal values from Bertin, foundations that would underpin his entire oeuvre.

However, Corot eventually moved beyond the stricter Neoclassicism of his teacher. While always retaining a sense of underlying structure, he developed a more personal, poetic, and atmospheric style, characterized by softer brushwork and a greater sensitivity to the nuances of light and mood. Corot became a pivotal figure himself, bridging the gap between Neoclassicism and the Barbizon School, and ultimately influencing the Impressionists. His journey exemplifies how Bertin's teaching provided a solid base from which students could launch their own distinct artistic explorations. Other artists who may have passed through his circle or were contemporaries developing landscape include figures like Léon Cogniet or Jules Coignet, though Corot and Michallon remain his most significant pupils.

Representative Works and Themes

Bertin's oeuvre is characterized by a consistent adherence to the Neoclassical landscape ideal. His paintings often depict serene, sunlit scenes inspired by the Italian countryside, even if painted in his Paris studio. These landscapes frequently feature classical architecture, such as temples, aqueducts, or villas, sometimes in ruins, evoking a sense of timelessness and connection to antiquity.

Specific representative works illustrate his style effectively:

Entrance to the Park of Saint-Cloud, 1800 (versions in MFA Boston and Getty): This work showcases his ability to render specific locations with clarity and order, albeit filtered through a Neoclassical lens. The careful arrangement of trees and the balanced composition are typical.

An Italian Villa (Cleveland Museum of Art): This painting exemplifies his idealized Italianate scenes, featuring picturesque architecture nestled within a harmonious natural setting, bathed in gentle light.

Forest with Apollo and Daphne (Cleveland Museum of Art): This work directly engages with classical mythology, placing the figures within a meticulously rendered, idealized forest landscape, demonstrating the principles of historical landscape.

Aqueduct near a Fortress (Cleveland Museum of Art): Here, the focus is on classical architectural elements integrated into the landscape, highlighting the Neoclassical interest in antiquity and structured composition.

Beyond his paintings, Bertin also produced lithographs. He published collections such as Recueil d'études d'arbres (Collection of Tree Studies) and Recueil d'essais de paysage (Collection of Landscape Essays/Sketches). These publications likely served both as pedagogical tools and as a way to disseminate his approach to rendering natural forms within a classical framework, further solidifying his influence.

Bertin's Place in Art History

Jean-Victor Bertin occupies a crucial, if sometimes overlooked, position in the history of French art. He was a master of the Neoclassical landscape, perfecting a style that blended the idealized traditions of Poussin and Claude Lorrain with the burgeoning interest in direct observation championed by his teacher, Valenciennes. His work represents the culmination of this specific approach to landscape painting.

He served as an important transitional figure. While firmly rooted in Neoclassicism, his emphasis on structure and his role as a teacher provided a foundation for artists like Corot who would move towards the greater naturalism of the Barbizon School and, eventually, Impressionism. Though Bertin himself did not embrace the Romantic emotionalism seen in contemporaries like Théodore Géricault or Eugène Delacroix, his dedication to landscape helped elevate the genre's status, paving the way for its dominance later in the century.

His influence can be seen primarily through his students, especially Corot, who adapted Bertin's lessons on structure and tonal harmony into a more lyrical and personal vision. While later 19th-century tastes shifted towards more overtly naturalistic or impressionistic styles, Bertin's contribution lies in his mastery of the Neoclassical form and his vital role in transmitting artistic knowledge and advocating for landscape painting within the powerful French academic system, standing alongside figures like Jacques-Louis David and Jean-Auguste-Dominique Ingres who dominated other Neoclassical genres.

Legacy and Collections

Jean-Victor Bertin's legacy endures primarily through his beautifully crafted paintings and his significant impact as an educator. He solidified the Neoclassical landscape style in France and played a key role in gaining academic respect for the genre through his advocacy for the Prix de Rome. His work provides a vital insight into the artistic tastes and academic priorities of the late 18th and early 19th centuries.

His paintings are held in the collections of major museums across the world, attesting to their historical importance and aesthetic quality. Notable institutions housing works by Bertin include:

The Louvre Museum, Paris

The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York (e.g., Deer in a Wood)

The J. Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles (e.g., Entrance to the Park of Saint-Cloud, 1800)

The Cleveland Museum of Art (holding several key examples)

The Museum of Fine Arts, Boston (e.g., Entrance to the Park of Saint-Cloud, 1800)

The National Gallery, London

Indianapolis Museum of Art (Paysage, 1804)

Palais des Beaux-Arts de Lille (Italian Landscape with Figures)

Musée des Beaux-Arts de Rouen (Italian Landscape: Monastery with Religious Figures)

The presence of his works in these prestigious collections ensures that his contribution to the history of landscape painting continues to be studied and appreciated. While perhaps less famous today than his student Corot or the later Impressionists like Claude Monet or Pierre-Auguste Renoir, Bertin remains a foundational figure whose art exemplifies the elegance and order of the Neoclassical vision of nature. His influence, transmitted through his teaching, resonated through subsequent generations of French landscape painters.

Conclusion

Jean-Victor Bertin was more than just a painter of idealized landscapes; he was a dedicated artist, an influential teacher, and a successful advocate for his chosen genre. In his meticulously composed and finely executed works, he captured the essence of the Neoclassical ideal, creating visions of nature characterized by harmony, order, and timeless beauty. Drawing inspiration from Poussin, Claude Lorrain, and his mentor Valenciennes, he perfected a style that defined landscape painting in France during his era.

Through his long career at the Salon and his role at the École des Beaux-Arts, where he taught future luminaries like Corot and Michallon, Bertin left an indelible mark on French art. He helped elevate landscape painting within the academic system and provided a crucial link between the classical tradition and the emerging naturalistic movements of the 19th century. Jean-Victor Bertin remains an essential figure for understanding the rich and complex evolution of landscape art in France.