Grace Carpenter Hudson stands as a significant figure in American art history, particularly noted for her sensitive and detailed portrayals of the Pomo Native American people of Northern California. An American artist by nationality, her life (1865-1937) was largely dedicated to documenting the lives, culture, and quiet dignity of the Pomo community residing near her home in Mendocino County. Her extensive body of work, numbering over 680 pieces, provides an invaluable ethnographic and artistic record of a people undergoing profound cultural change at the turn of the 20th century. Hudson achieved considerable recognition during her lifetime, distinguishing herself not only through her unique subject matter but also through her technical skill and empathetic approach.

Early Life and Artistic Formation

Grace Carpenter was born on February 21, 1865, in Potter Valley, California. She hailed from a family deeply connected to the region and possessing artistic inclinations. Her mother, Helen McCowen Carpenter, was a notable figure in her own right, serving as one of the area's first white school teachers, while her father, Aurelius Ormando Carpenter, worked as a skilled landscape and panoramic photographer and journalist. This environment undoubtedly fostered Grace's early interest in observation and visual representation. Her parents documented the developing landscape and the local Pomo people through photography, providing an early exposure to the subjects that would later define her career.

Recognizing her burgeoning talent, her family supported her formal art education. At the young age of fourteen, in 1879, Grace moved to San Francisco to attend the California School of Design (now the San Francisco Art Institute). This institution emphasized drawing from life rather than mere copying, a principle that profoundly shaped her artistic methodology. During her time there, she studied under respected artists such as Oscar Kunath and Raymond Dabb Yelland, the latter being a well-regarded landscape painter. Virgil Williams served as the director during part of her tenure. Her precocious skill was evident when, at sixteen, she created a full-length self-portrait in crayon that won her an award, showcasing her technical proficiency early on.

However, her formal studies were abruptly interrupted. A youthful romance led to her elopement with a man named William Davis, who was fifteen years her senior. This act, undertaken against her parents' wishes, resulted in the cessation of her studies at the School of Design. Though this marriage was relatively short-lived, this period marked a departure from formal training and a turn towards self-directed artistic development, perhaps instilling a sense of independence that would characterize her later career.

Return to Ukiah and a Fateful Partnership

Following the end of her first marriage, Grace returned to Mendocino County, settling in Ukiah around 1885. She initially put her artistic skills to use by teaching painting and assisting in her parents' photography studio. This period allowed her to reconnect with the local landscape and the Pomo community she had known since childhood. In 1889, she established her own small art studio, signaling her commitment to pursuing a professional career as a painter.

A pivotal moment in her life and career occurred in 1890 when she married Dr. John Wilz Napier Hudson. John Hudson was an physician with a burgeoning interest in anthropology and linguistics. Their union proved to be a deeply synergistic partnership, both personally and professionally. Influenced perhaps by Grace's deep connection to the Pomo people and her burgeoning artistic focus on them, John eventually abandoned his medical practice to dedicate himself fully to the study of Pomo ethnography and archaeology, as well as broader studies of Native American cultures. His scholarly pursuits provided invaluable context and information for Grace's artwork, while her paintings offered a visual dimension to his research.

The Pomo People: A Life's Work

Grace Carpenter Hudson's artistic legacy is inextricably linked to her depictions of the Pomo people. Beginning in earnest shortly after her marriage to John, she embarked on what would become her life's primary artistic mission: documenting the Pomo individuals and their way of life. She produced an extensive series of numbered oil paintings, ultimately exceeding 680 works, almost exclusively focused on Pomo subjects, particularly children.

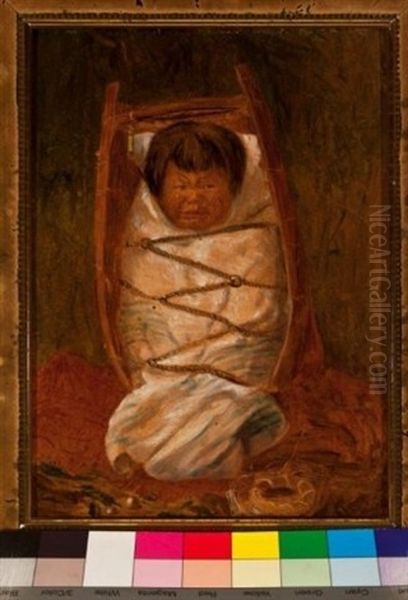

Her approach was marked by sensitivity and a desire to portray her subjects with dignity and individuality, countering the often stereotypical or romanticized images of Native Americans prevalent at the time. Her paintings captured the nuances of daily existence: children playing, mothers caring for infants, elders reflecting, individuals engaged in traditional activities like basket weaving (a Pomo specialty), hunting, fishing, and participating in ceremonies. She depicted moments of quiet domesticity, gentle interactions, and the resilience of a people facing immense pressure from encroaching white settlement and governmental policies aimed at assimilation.

A breakthrough came in 1891 with her painting titled National Thorn. This work depicted a Pomo baby sleeping soundly in a traditional cradleboard. Its poignant charm and technical skill garnered significant attention and marked the beginning of her focused series. Another key early work, Little Mendocino (1893), also featuring a Pomo infant, further cemented her reputation and was exhibited prominently, bringing her wider acclaim. These paintings, often featuring solitary children with expressive eyes, became her trademark, resonating with audiences for their perceived innocence and pathos, though they also subtly documented cultural details in clothing, cradleboards, and adornments.

Achieving National Recognition

The quality and unique subject matter of Hudson's work soon brought her national attention. A major milestone was the World's Columbian Exposition held in Chicago in 1893. This massive international fair was a crucial venue for artists seeking recognition. Hudson exhibited several paintings there, including Little Mendocino, and received honorable mentions or awards (sources vary on the exact accolade), significantly boosting her profile. Her work was praised for its technical merit and its sensitive portrayal of indigenous subjects.

Following the Chicago exposition, demand for her paintings grew substantially. She became one of the most commercially successful female artists in the United States at the time. Her work was frequently reproduced as illustrations in popular national magazines, including Overland Monthly, Cosmopolitan, and Sunset Magazine, bringing her images into homes across the country. This widespread exposure further solidified her reputation as a painter specializing in Native American subjects, particularly children. She carefully cataloged her numbered oil paintings, maintaining meticulous records of subjects, dates, and often the prices paid, reflecting her professional approach to her burgeoning career.

Broadening Artistic Horizons

While the Pomo remained her central focus, Hudson occasionally turned her attention to other indigenous groups, often in collaboration with her husband's ethnographic work. In 1901, she spent approximately nine months in the Territory of Hawaii. There, she undertook a commission to paint portraits of Native Hawaiian children, applying her characteristic style and sensitivity to a different cultural context. This trip represented a significant geographical and thematic expansion of her work.

A few years later, in 1904, Grace and John Hudson were commissioned by the Field Columbian Museum (now the Field Museum of Natural History) in Chicago. Their task was to travel to Oklahoma Territory to document the Pawnee people. John collected artifacts and conducted ethnographic research, while Grace created a series of paintings depicting Pawnee individuals and scenes. This commission underscored her growing reputation as an artist whose work possessed ethnographic value, aligning her with institutions dedicated to the study and preservation of Native American cultures. These excursions demonstrated her willingness to apply her skills beyond her familiar Mendocino County setting.

Artistic Style, Technique, and Mediums

Grace Carpenter Hudson's artistic style is best characterized as a form of gentle realism infused with considerable empathy. She possessed a keen eye for detail, meticulously rendering textures of clothing, basketry, and the expressive features of her subjects. Her palette was often warm and rich, contributing to the intimate and approachable quality of her work. While adhering to realistic representation, her paintings often evoked a sense of quietude and sometimes melancholy, perhaps reflecting the precarious situation of the Pomo people during that era.

Her work stood in contrast to much of the prevailing "Western art" of the time. While artists like Frederic Remington and Charles M. Russell often focused on dramatic scenes of cowboys, conflict on the plains, or romanticized visions of Native American warriors, Hudson concentrated on the domestic sphere, the lives of women and children, and the continuity of cultural practices within the Pomo community. Her focus was less on action and more on character and cultural documentation through portraiture and genre scenes.

Although best known for her oil paintings, Hudson was proficient in various mediums. Her early award-winning self-portrait was a crayon drawing, and she also worked in watercolor, pen and ink, and charcoal throughout her career. Her drawings and sketches often served as studies for larger oil paintings but also stand as accomplished works in their own right. Representative later works, such as Woodpecker (Ka-Tocht) (1915) and The Betrothed (Ta-Le-A), continued to showcase her skill in capturing individual personality and cultural attire with precision and sensitivity. Her style remained consistent throughout her career, marked by its clarity, warmth, and focus on the human element.

A Collaborative Spirit: The Hudsons' Partnership

The marriage of Grace Carpenter and John Hudson was a remarkable example of a collaborative partnership that blended art and science. John's transition from medicine to ethnography was deeply intertwined with Grace's artistic focus. He became a dedicated student of Pomo language, customs, and material culture, amassing extensive field notes and a significant collection of Pomo artifacts (baskets, tools, regalia). Much of this collection eventually went to major institutions like the Field Museum and, later, formed the core of the Grace Hudson Museum's ethnographic holdings.

Their collaboration was direct and mutually beneficial. John's research provided Grace with accurate cultural context, details about traditional practices, and introductions to potential subjects within the Pomo community. Grace's paintings, in turn, offered compelling visual documentation that complemented John's written records and artifact collections. They often traveled together on research trips, including their expeditions to Hawaii and Oklahoma. Their home, which they designed and built in Ukiah in 1911 and named "The Sun House," became a hub for their joint work—a place where art was created, research was conducted, and Pomo culture was studied and respected.

Context in American Art

Grace Carpenter Hudson occupied a unique niche within the landscape of American art at the turn of the 20th century. As a female artist achieving significant professional success, she navigated a field still largely dominated by men. While contemporaries like Mary Cassatt and Cecilia Beaux achieved fame painting impressionistic scenes or formal portraits often set in East Coast or European society, Hudson focused her gaze on a marginalized indigenous community in rural California, developing a distinct regional and thematic specialty.

Her work can be situated within the broader tradition of artists depicting Native American life. She followed earlier figures like George Catlin and Karl Bodmer, who documented various tribes in the first half of the 19th century, often with a more overtly ethnographic or exploratory purpose. However, Hudson's approach was generally more intimate and less focused on the "exotic" than some of her predecessors. Compared to the Taos Society of Artists founders like E. Irving Couse or Joseph Henry Sharp, who often painted Southwestern Pueblo peoples slightly later, Hudson's work maintained a consistent focus on a single tribal group (the Pomo) and often emphasized the portrayal of children. Her realism and focus on daily life differed significantly from the dramatic, action-oriented Western scenes of Frederic Remington or Charles M. Russell.

Within California, her work stands apart from the dominant landscape tradition represented by figures like William Keith, Thomas Hill, and Albert Bierstadt, whose grand canvases celebrated the state's natural scenery. While sharing a California context, her focus remained steadfastly on its original inhabitants. Later artists like Maynard Dixon would also depict Native Americans, often with a more modernist sensibility and a focus on the vastness of the Western landscape surrounding them, contrasting with Hudson's more intimate, figure-focused compositions. Her teachers, Oscar Kunath and Raymond Dabb Yelland, represented the academic and landscape traditions she initially trained in but ultimately diverged from in her specialized career path.

Challenges and Perseverance

Despite her professional success, Grace Carpenter Hudson's life was not without challenges. She reportedly suffered from periods of ill health, sometimes necessitating breaks from her demanding painting schedule. Like many artists with connections to San Francisco, she likely faced losses related to the devastating 1906 earthquake and fire, which destroyed galleries, studios, and storage facilities where artworks might have been held.

Furthermore, the very nature of her work involved navigating complex relationships between the white community and the Pomo people. While she developed close ties with many Pomo families who allowed her to paint them and their children, her work was also consumed by an audience whose understanding of Native American life was often limited or stereotypical. Balancing artistic integrity, ethnographic accuracy (as understood then), and commercial appeal was an ongoing aspect of her career. Nevertheless, she persevered, continuing to paint prolifically for over four decades, driven by a clear dedication to her chosen subject. She largely ceased painting around 1935, just two years before her death.

Legacy: The Sun House and Enduring Significance

Grace Carpenter Hudson died in Ukiah on March 24, 1937. Her husband, John Hudson, had passed away the previous year. In her will, Grace bequeathed their home, The Sun House, and its contents—including remaining paintings, John's vast collection of Pomo artifacts, his extensive field notes, and photographs—to the City of Ukiah with the intention of creating a museum.

Today, the Grace Hudson Museum & Sun House stands as her most tangible legacy. The Sun House itself, a beautiful Craftsman-style bungalow they designed, is a California Historical Landmark and open to the public. The adjacent museum preserves and exhibits her extensive body of work alongside John Hudson's ethnographic collections, providing a rich resource for understanding both Pomo culture and the Hudsons' unique collaborative life. Her paintings continue to be appreciated for their artistic merit, their historical value as documents of Pomo life during a period of intense cultural transition, and their sensitive portrayal of individual humanity. Grace Carpenter Hudson remains a vital figure in the history of American Western art and ethnographic representation, a dedicated chronicler who used her considerable artistic skill to preserve the world of the Pomo people she knew so well.

Conclusion

Grace Carpenter Hudson carved a unique and enduring path in American art. Through decades of dedicated work, she created an unparalleled visual record of the Pomo people of Northern California, capturing their culture, traditions, and individual lives with remarkable sensitivity and skill. Working in close partnership with her ethnographer husband, John Hudson, she achieved national recognition, bringing the quiet dignity of her Pomo subjects into the public eye. Her realistic style, focused on intimate portraits and scenes of daily life, offered a distinct perspective within Western American art. Today, her legacy is preserved not only in museums and private collections but most significantly at the Grace Hudson Museum & Sun House in Ukiah, which stands as a testament to her artistic vision and her profound connection to the Pomo community.