Eugène François Deshayes (1862-1939) stands as a significant, if sometimes overlooked, figure within the rich tapestry of French Orientalist painting. Born in the vibrant colonial city of Algiers, his life and art were inextricably linked to the landscapes, cultures, and peoples of North Africa. His work, characterized by a sensitive rendering of light and atmosphere, captured the allure of the Mediterranean and the stark beauty of the desert, contributing to the European visual understanding—and construction—of the "Orient" during the late 19th and early 20th centuries. This exploration will delve into his biography, artistic development, key works, and his position within the broader context of Orientalist art and his contemporaries.

Early Life and Artistic Awakening in Algiers

Eugène François Deshayes was born on May 26, 1862, in Algiers, the capital of French Algeria. His connection to this North African territory was deep-rooted; his father, Adolphe Deshayes, had been a soldier who participated in the siege of Constantine in 1837. Wounded during this military campaign, Adolphe was subsequently assigned to an administrative role within the colonial government in Algiers, where he later married. Eugène was born at the Mustapha hospital, a common birthplace for many Europeans in the city. Tragically, young Eugène experienced the loss of his parents at an early age and was subsequently raised by his older brother. This early immersion in the sights, sounds, and unique cultural blend of Algiers undoubtedly shaped his nascent artistic sensibilities.

Despite a childhood marked by personal loss, Deshayes exhibited a keen interest in drawing and painting from a young age. He pursued formal artistic training at the École Nationale des Beaux-Arts d'Alger (Algiers National School of Fine Arts). While his performance there was initially described as somewhat unremarkable, his passion remained undeterred. He received guidance from artists such as Emile Charles Labbé, a painter and professor at the school, who would have introduced him to academic principles and techniques. The artistic environment of Algiers, though perhaps not as central as Paris, was nonetheless active, with local artists and visiting European painters contributing to a burgeoning colonial art scene.

A pivotal encounter during his formative years in Algiers was with the acclaimed French painter Jules Bastien-Lepage. Bastien-Lepage, known for his contributions to Naturalism and his sensitive rural scenes, was visiting Algiers for health reasons. The two met, possibly through shared artistic circles or at Deshayes' family residence, and a friendship developed. Bastien-Lepage, recognizing the young man's potential, offered encouragement and guidance. This mentorship proved crucial, as it was through Bastien-Lepage's support and influence that Deshayes secured a scholarship in 1885. This scholarship was his passport to Paris, the undisputed art capital of the Western world, and the next significant phase of his artistic development.

The Parisian Crucible: Mentorship and Development

Arriving in Paris around 1885, Eugène Deshayes was thrust into the heart of a dynamic and competitive art world. The city was a melting pot of artistic styles, from the established academic tradition to the revolutionary stirrings of Impressionism and Post-Impressionism. For a young artist from Algiers, it must have been both exhilarating and daunting. He enrolled at the prestigious École des Beaux-Arts in Paris, the bastion of academic art training in France.

Crucially, Deshayes gained entry into the atelier (studio) of Jean-Léon Gérôme, one of the most famous and influential academic painters of the era. Gérôme was a master of historical painting, sculpture, and, significantly for Deshayes, a leading figure in the Orientalist movement. His works were renowned for their meticulous detail, polished finish, and often dramatic or anecdotal depictions of scenes from North Africa, the Middle East, and the classical world. Studying under Gérôme would have provided Deshayes with rigorous training in drawing, composition, and the techniques of oil painting, all within an environment that valued precision and historical accuracy, albeit often filtered through a romanticized lens when it came to Orientalist subjects. Gérôme reportedly held his young student in high regard, recognizing his talent and dedication.

During his time in Paris, Deshayes also formed connections with other artists. He is known to have shared lodgings on the Rue de Seine with a fellow Algerian painter named Bertrand. This cohabitation would have provided mutual support and a continued link to his North African roots, even amidst the Parisian art scene. The Rue de Seine, located in the heart of the Left Bank, was historically an area frequented by artists, writers, and intellectuals, placing Deshayes in a stimulating environment. He would have been exposed to the annual Salons, the grand public exhibitions that could make or break an artist's career, and to the diverse artistic currents flowing through the city. Artists like Pascal Dagnan-Bouveret, another prominent pupil of Gérôme and a friend of Bastien-Lepage, would have been part of this wider artistic milieu, championing a form of naturalistic academicism.

The combined influence of his early life in Algiers, the mentorship of Bastien-Lepage with his emphasis on natural observation, and the rigorous academic and Orientalist training under Gérôme, forged the foundations of Deshayes' artistic identity. He was equipped with technical skill and a profound, personal connection to the subjects that would come to define his oeuvre.

The Emergence of an Orientalist Painter

By 1890, Eugène Deshayes was ready to launch his professional career. He held his first significant exhibition at the Dru Gallery in Algiers, a fitting return to his hometown to showcase his matured artistic vision. This was soon followed by his debut at the highly influential Salon des Artistes Français in Paris. Exhibiting at the Paris Salon was a critical step for any ambitious artist, providing visibility and the opportunity for critical recognition and sales. Deshayes would continue to exhibit regularly at the Salon throughout his career, a testament to his consistent output and acceptance within the established art system.

His chosen specialty was Orientalism, a genre that had captivated European audiences since the early 19th century with pioneers like Eugène Delacroix, whose journey to Morocco in 1832 had a profound impact on his art and on the movement itself. Orientalism, in its broadest sense, referred to the depiction of subjects drawn from North Africa, the Middle East (the "Levant"), and sometimes Asia, by Western artists. It encompassed a wide range of themes: bustling souks, serene mosque interiors, nomadic encampments, desert caravans, portraits of local inhabitants, and, more controversially, imagined harem scenes. Artists like Jean-Auguste-Dominique Ingres, though he never traveled to the East, famously painted odalisques that became iconic Orientalist images.

Deshayes' Orientalism, however, was rooted in direct experience. Having grown up in Algiers, he possessed an intimacy with the North African environment that distinguished his work from that of artists who made only fleeting visits. His paintings focused primarily on the landscapes of the Mediterranean coast and the arid expanses of the Arabian desert. He was particularly drawn to the quality of light in North Africa – the brilliant sunshine, the subtle hues of dawn and dusk, and the way light interacted with the architecture and the natural environment. His works often conveyed a sense of tranquility and timelessness, inviting the viewer to contemplate the serene beauty of these locales.

He was not alone in this pursuit. The late 19th century saw a flourishing of Orientalist painting. Artists such as Gustave Guillaumet had already dedicated much of their careers to depicting Algerian scenes with a remarkable degree of empathy and realism. Eugène Fromentin, both a painter and a writer, had earlier captured the landscapes and equestrian scenes of Algeria in works like "Falconry in Algeria." Later, artists like Étienne Dinet (who eventually converted to Islam and took the name Nasr'Eddine Dinet) would immerse themselves even more deeply in Algerian culture, producing works of striking authenticity. Deshayes' contribution lay in his consistent focus on landscape and atmospheric effects, often with a poetic sensibility.

Artistic Style and Thematic Concerns

Eugène François Deshayes' artistic style can be described as a harmonious blend of Realism and Romanticism, filtered through the specific lens of Orientalism. His academic training under Gérôme instilled in him a respect for accurate drawing and careful composition, hallmarks of Realism. However, his choice of subject matter and his evocative portrayal of atmosphere often leaned towards a Romantic sensibility, emphasizing the beauty, exoticism, and sometimes the melancholic grandeur of the North African landscape.

He worked proficiently in both oil and watercolor. His oil paintings often possess a rich texture and depth of color, allowing him to capture the intense Mediterranean light and the subtle gradations of color in the desert. His watercolors, on the other hand, demonstrate a lighter touch, ideal for capturing fleeting atmospheric effects and the translucent quality of light. Regardless of the medium, his brushwork was generally controlled yet expressive, avoiding the highly polished, almost photographic finish of some academic Orientalists like Ludwig Deutsch or Rudolf Ernst, yet more detailed than the looser style of the Impressionists.

Deshayes' thematic concerns were deeply rooted in his North African experience. He painted the bustling ports along the Mediterranean coast, capturing the interplay of boats, water, and coastal architecture. The vibrant colors of fishing vessels, the shimmering reflections on the sea, and the characteristic forms of North African towns provided rich visual material. He also ventured into the interior, depicting the vastness of the Sahara, the nomadic life of Bedouin tribes with their tent encampments, and the oases that offered respite from the desert's harshness. These scenes often included figures, but they were typically integrated into the landscape, serving to animate the scene rather than being the primary focus of a narrative.

A significant portion of his work was dedicated to the pure landscape, exploring the unique flora and fauna of Southern Europe and North Africa. He meticulously observed and rendered the characteristic vegetation of the Mediterranean scrubland and the desert, as well as the quality of the light at different times of day. Sunsets over the sea or the desert were a recurring motif, allowing him to explore a rich palette of colors and dramatic lighting effects. His deep understanding of these environments enabled him to convey not just their visual appearance but also their palpable atmosphere. His approach can be compared to that of other landscape-focused Orientalists like Alexis Delahogue and his twin brother Eugène Jules Delahogue, or Henri Carnier, who also specialized in North African scenes.

Key Works and Signature Motifs

While a comprehensive catalogue raisonné of Deshayes' work might be elusive, several titles and descriptions give us insight into his signature motifs and artistic achievements. His paintings often carried descriptive titles that clearly indicated their subject matter.

One of his noted works is "Casablanca," which is described as depicting a Mediterranean sunset. This subject would have allowed Deshayes to showcase his skill in rendering dramatic light and color, with the warm hues of the setting sun reflecting on the water and illuminating the coastal city. Such scenes were popular with audiences, evoking a sense of romantic escapism.

"Mediterranean landscape" is a broader title that likely encompasses many of his coastal scenes. These could range from views of specific ports like Algiers or Tunis to more generalized depictions of the rugged coastline, dotted with white-washed buildings and lush vegetation. The clarity of the Mediterranean light and the deep blue of the sea would have been central elements.

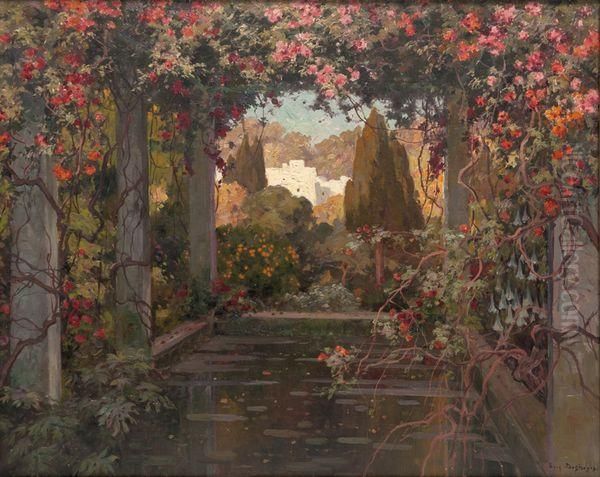

A work titled "Jardin fleuri en Afrique du Nord" (Flowering Garden in North Africa), or a similar subject described as "Calanque près de Bougie, Algérie" (Calanque near Bougie, Algeria), points to his interest in the more intimate aspects of the North African landscape. Bougie (now Béjaïa) is a coastal city in Algeria known for its picturesque bays (calanques) and verdant surroundings. A painting of a flowering garden would highlight the vibrant colors of local flora against the backdrop of traditional architecture or the natural landscape, showcasing the surprising fertility found in parts of this predominantly arid region.

Another representative theme is captured in titles like "Bateau sur la grève" (Boat on the Shore) or the description "Boats sailing near a rocky coast." These marine subjects were a significant part of his output, reflecting his appointment as an official painter for the French Navy. He would have depicted various types of local watercraft, from fishing boats to larger sailing vessels, often set against dramatic coastlines or within busy harbors. The textures of weathered wood, billowing sails, and the dynamic movement of water would have been key elements.

His desert landscapes, though perhaps less specifically titled in the provided information, were a cornerstone of his Orientalist work. These would have featured sweeping vistas of sand dunes, rugged mountains, and the occasional oasis or Bedouin encampment, often under the vast expanse of the North African sky. The challenge in these works lay in capturing the subtle variations in color and texture of the sand, the intense heat, and the profound sense of solitude and immensity. Artists like Jean Discart, an Austro-French Orientalist, also excelled in depicting desert scenes with remarkable detail.

Recognition, Accolades, and Official Appointments

Eugène François Deshayes achieved considerable success and recognition during his lifetime. His regular participation in the Paris Salon des Artistes Français was a mark of his established position in the art world. These Salons were juried exhibitions, and acceptance was a significant achievement. He didn't just exhibit; he also received accolades for his work, including medals that acknowledged his artistic merit.

One of the most prestigious honors bestowed upon him was his appointment as an official Peintre de la Marine (Painter of the French Navy). This official title was granted to artists whose work demonstrated a particular excellence in depicting maritime subjects. It often came with opportunities to travel with the navy and access to naval installations, further enriching his repertoire of coastal and sea scenes. This appointment underscores his skill in capturing the essence of the Mediterranean world, both its landscapes and its maritime life. Other notable artists who held this title, though from different periods, include Claude Joseph Vernet in the 18th century and Marin-Marie in the 20th century, highlighting the prestige of the role.

Further testament to his standing was the award of a gold medal at a World's Fair (Exposition Universelle). These international expositions were grand showcases of industrial, scientific, and artistic achievement, and receiving a medal was a significant international honor. He was also made a Chevalier de la Légion d'Honneur (Knight of the Legion of Honour), France's highest order of merit, a recognition of his distinguished contributions to French art and culture.

His reputation extended beyond France. His paintings were sought after by collectors and found their way into collections in other European countries such as Great Britain, Germany, and Spain, as well as across the Atlantic in the United States. Naturally, his work was also popular in North Africa itself, particularly in Algeria, Tunisia, and Morocco, where European colonists and discerning locals appreciated his depictions of their environment. He also undertook decorative commissions, such as creating decorative panels for the Algerian pavilion at an exposition and painting a dining table for the summer palace, likely the governor's residence in Algiers. These commissions indicate a high level of trust in his artistic abilities and his suitability for official and prestigious projects.

Deshayes and His Contemporaries: The "School of Algiers"

Eugène Deshayes operated within a vibrant ecosystem of artists, particularly those associated with Orientalism and the colonial art scene in French North Africa, sometimes loosely referred to as the "School of Algiers" (École d'Alger). This was not a formal school with a unified manifesto, but rather a term used to describe the diverse group of European artists who lived and worked in Algeria, drawing inspiration from its landscapes and cultures.

His master, Jean-Léon Gérôme, was a towering figure whose influence extended to many students who pursued Orientalist themes, such as the American Frederick Arthur Bridgman, who also spent considerable time in North Africa and whose detailed genre scenes were highly popular. Bridgman, like Deshayes, brought a firsthand knowledge of the region to his canvases. Another contemporary, Benjamin-Constant, was known for his large-scale, dramatic Orientalist compositions, often focusing on Moroccan subjects and harem scenes, which differed in temperament from Deshayes' more landscape-focused and tranquil works.

In Algeria itself, Deshayes would have been aware of artists like Alphonse-Étienne Dinet, who, as mentioned, became deeply integrated into Algerian life. Dinet's work is characterized by its sympathetic and insightful portrayal of the Algerian people and their customs. While Deshayes focused more on landscape, the human element in his paintings, though often secondary, was informed by the same environment that Dinet depicted with such intimacy. The Spanish painter Mariano Fortuny, though he died relatively young in 1874, had also made a significant impact with his brilliantly lit and technically dazzling Orientalist scenes, particularly from Morocco, influencing a generation of artists with his vibrant style.

The artistic community in Algiers also included figures like Hippolyte Lazerges and his son Jean-Baptiste Paul Lazerges, both of whom painted Algerian subjects. The aforementioned Alexis Delahogue and Henri Carnier were also part of this milieu, specializing in North African landscapes and scenes of daily life. The interactions, shared exhibitions, and mutual influences among these artists created a rich artistic dialogue centered on the North African experience. Deshayes' friendship with the painter Bertrand in Paris further illustrates these networks that connected artists from the colony with the metropole.

The context of French colonialism is, of course, inseparable from the Orientalist art produced in Algeria. While artists like Deshayes undoubtedly felt a genuine admiration for the landscapes and cultures they depicted, their presence and perspective were part of a larger colonial enterprise. Modern art historical interpretations often critically examine the power dynamics inherent in Orientalist art, questioning the ways in which it may have reinforced stereotypes or presented a romanticized, depoliticized view of colonized lands. However, within its historical context, Deshayes' work was appreciated for its aesthetic qualities and its ability to transport viewers to what was perceived as an exotic and captivating world.

Anecdotes, Controversies, and Later Life

While major scandals or dramatic public controversies do not prominently feature in the known biography of Eugène François Deshayes, the life of any artist operating within a competitive field like the Parisian art world would have had its share of professional rivalries and critical debates. The very nature of Orientalism, as it evolved, became a subject of discussion. By the early 20th century, new artistic movements like Fauvism and Cubism were challenging traditional representational art, and Orientalism, with its academic underpinnings, might have been seen as more conservative by the avant-garde.

However, Deshayes' consistent success, his official appointments, and the widespread sale of his works suggest that he navigated his career skillfully and maintained a strong reputation. The "controversy" associated with his work today is more of a retrospective critique of the Orientalist genre itself – its tendency to exoticize, to create a Western fantasy of the "Orient," and its relationship with colonialism. This is a broader art historical debate rather than a specific controversy attached to Deshayes personally during his lifetime. His personal experience of being born and raised in Algiers might have given his work a nuance that differed from artists who were merely visitors, but he was still a European artist depicting a colonized land for a predominantly European audience.

His family background, with his father's military service in the French conquest of Algeria and his own upbringing in the colonial capital, firmly places him within the Franco-Algerian milieu. The early loss of his parents and being raised by his brother are personal details that hint at a challenging childhood, perhaps fostering a resilience and independence that served him in his artistic pursuits.

Deshayes continued to paint and exhibit throughout his life. He remained deeply connected to Algiers, the city of his birth and a constant source of inspiration. It was there, in Algiers, that Eugène François Deshayes passed away in 1939, at the age of 77 (or 71, depending on the precise birth/death calculation, though 1862-1939 is typically 76-77 years). His death occurred on the cusp of World War II, a period that would dramatically reshape the world and the colonial empires that had fostered genres like Orientalism.

Legacy and Conclusion

Eugène François Deshayes left behind a significant body of work that captures the unique beauty and atmosphere of North Africa, particularly Algeria and the wider Mediterranean region. As an Orientalist painter, he contributed to a genre that, while complex and subject to modern critique, remains a fascinating and visually rich chapter in 19th and early 20th-century art history. His paintings are valued for their technical skill, their evocative depiction of light and landscape, and their ability to convey a sense of place.

His position as a Peintre de la Marine and a Chevalier de la Légion d'Honneur attests to the high esteem in which he was held during his lifetime. His works provided a window onto North Africa for European audiences, shaping their visual understanding of the region. While he may not be as universally recognized today as some of the pioneering figures of Orientalism like Delacroix or his own master Gérôme, Deshayes holds a respectable place among the second generation of Orientalist painters who specialized in and often had deep personal connections to the lands they depicted.

His art serves as a visual record of a specific historical period and a particular European perspective on North Africa. For art historians, his work offers insights into the aesthetics of late academic painting, the enduring appeal of Orientalist themes, and the artistic life within the French colonial context. For art lovers, his paintings continue to resonate with their serene beauty, their masterful handling of light, and their evocative portrayal of landscapes that still hold a powerful allure. Eugène François Deshayes was a dedicated artist whose life and work were a testament to his profound and enduring connection to the sun-drenched lands of North Africa.