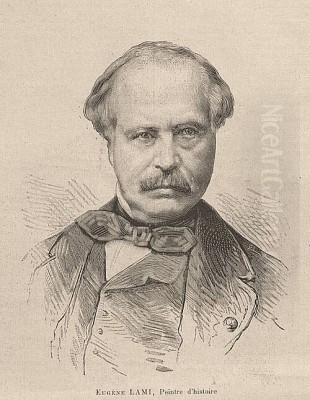

Eugène Louis Lami stands as a significant figure in 19th-century French art, a versatile talent whose work spanned multiple genres and media. Born in Paris on January 12, 1800, and passing away in the same city on December 19, 1890, Lami's long life witnessed dramatic shifts in French politics and society, from the Napoleonic era's aftermath through the July Monarchy, the Second Republic, the Second Empire, and into the Third Republic. He navigated these changes not just as a witness but as an active recorder, employing his skills as a painter, watercolorist, lithographer, illustrator, and designer to capture the essence of his time. His legacy is one of elegance, meticulous detail, and a remarkable ability to portray both the grandeur of state occasions and the intimate nuances of everyday elite life.

Early Life and Artistic Formation

Lami's artistic journey began in his native Paris. His initial training took place in the studio of Horace Vernet, a prominent painter known for his battle scenes and historical subjects. This early exposure to military themes would prove influential throughout Lami's career. Seeking more formal instruction, he enrolled at the prestigious École des Beaux-Arts in Paris.

At the École, Lami studied under the tutelage of Baron Antoine-Jean Gros, one of Jacques-Louis David's most famous pupils and a leading figure in French historical painting, particularly noted for his large-scale depictions of Napoleonic campaigns. Gros's influence likely reinforced Lami's interest in historical and military subjects while grounding him in the academic traditions of draughtsmanship and composition.

A pivotal element in Lami's development was his encounter with the English artist Richard Parkes Bonington. Though Bonington's life was tragically short (1802-1828), his impact on French art, particularly in the medium of watercolor, was profound. Lami learned watercolor techniques from Bonington, mastering the medium's transparency and luminosity. This skill would become one of Lami's hallmarks, distinguishing his work and contributing significantly to his reputation. During his formative years, he also associated with other emerging talents like Paul Delaroche and Camille Roqueplan, further immersing himself in the vibrant artistic milieu of Restoration Paris.

The Rise of a Lithographer

Before achieving widespread fame as a painter, Lami first made a significant mark in the burgeoning field of lithography. He began working in this medium around 1817, quickly demonstrating a natural aptitude for its expressive potential. Lithography allowed for wider dissemination of images and was particularly suited to illustration and topical subjects.

His breakthrough came early. In collaboration with his former teacher, Horace Vernet, Lami produced a highly successful series titled Collection des uniformes des armées françaises de 1791 à 1814 (Collection of Uniforms of the French Armies from 1791 to 1814), published between 1822 and 1825. This extensive work, comprising numerous plates, meticulously documented the diverse and often elaborate uniforms worn by French soldiers during the Revolutionary and Napoleonic Wars.

The Collection des uniformes was lauded for its accuracy and detail, establishing Lami as a leading specialist in military illustration. It showcased his keen eye for costume, his precise draughtsmanship, and his ability to convey the distinct character of different regiments. This series cemented his reputation in military art circles and brought his name to public attention. He would continue to produce lithographs throughout his career, including depictions of contemporary events and illustrations for literary works, often rivaling contemporaries like Nicolas Toussaint Charlet and Auguste Raffet in popularity and skill within the medium.

Mastery of Watercolour

Eugène Lami's proficiency in watercolor, significantly influenced by Richard Parkes Bonington, became one of his most celebrated attributes. He embraced the medium's unique qualities, developing a style characterized by delicate washes, clear lines, and a remarkable sensitivity to light and atmosphere. His watercolors often possess an elegance and refinement that perfectly suited his subject matter, particularly scenes of high society.

Lami became a leading proponent of watercolor in France at a time when it was still gaining acceptance as a serious artistic medium, often seen as secondary to oil painting. His technical skill and the appeal of his works helped elevate the status of watercolor painting. His dedication to the medium culminated in his role as a founding member of the prestigious Société des Aquarellistes Français (Society of French Watercolourists) in 1879, an organization that played a crucial role in promoting the art form.

His watercolors covered a wide range of subjects, from intimate interiors and social gatherings to historical reconstructions and costume studies. Works like An Embracing Couple (1881, Los Angeles County Museum of Art) exemplify his ability to capture tender moments with subtlety and grace. Other pieces, such as Officer of the Guard Grenadiers and Officer of the Foot Grenadiers, showcase his continued interest in military subjects, rendered with the characteristic finesse of his watercolor technique. His skill rivaled that of English masters like J.M.W. Turner, though Lami focused more on figurative and narrative subjects.

Historical Painter and Official Recognition

While excelling in lithography and watercolor, Lami also pursued history painting in oils, tackling significant events and historical figures. His training under Gros provided a strong foundation for these larger-scale works. One notable example is his painting depicting Charles I of England being led to Carisbrooke Castle. This work, completed around 1829, captured the attention of King Louis-Philippe I.

The King, known as the "Citizen King," was actively commissioning art for his historical museum at Versailles, aiming to reconcile France's monarchist, revolutionary, and Napoleonic pasts. He purchased Lami's painting of Charles I, and it was displayed prominently in the French National Assembly for over a century, a testament to its perceived quality and historical significance. This royal patronage significantly boosted Lami's standing. He also received official recognition earlier, being awarded a medal at the Paris Salon by King Charles X.

Another major historical work is The Battle of New Orleans (Louisiana State Museum). This large canvas depicts the final major battle of the War of 1812, an American victory over British forces. Lami's painting is noted for its detailed and dramatic portrayal of the conflict, reportedly capturing specific moments and actions of soldiers during the engagement, showcasing his ability to blend historical accuracy with dynamic composition, a skill perhaps honed by his earlier work with Horace Vernet but distinct from the grand Romanticism of Eugène Delacroix or the Neoclassical precision of Jean-Auguste-Dominique Ingres.

Chronicler of Society and Royalty

Beyond military and historical themes, Lami became renowned as an astute observer and elegant chronicler of contemporary French high society, particularly during the July Monarchy (1830-1848) and the Second Empire (1852-1870). His watercolors and paintings captured the fashions, manners, and opulent settings of the Parisian elite with unparalleled charm and detail.

He depicted balls, receptions, soirées, and intimate gatherings in the grand salons of Paris and the royal palaces. His works offer a vivid glimpse into the lives of the aristocracy and the wealthy bourgeoisie, documenting their attire, décor, and social rituals. He became a favored artist of the Orléans family during the reign of Louis-Philippe, recording their life at the Tuileries Palace and other royal residences.

Later, under Napoleon III, Lami continued to document the splendors of the Second Empire court. His paintings and watercolors from this period capture the era's luxurious atmosphere and the elaborate festivities hosted by the Emperor and Empress Eugénie. He was, in essence, a visual historian of elite social life, preserving the ephemeral elegance of his time with a delicate touch and a keen eye for detail. His work in this vein provides invaluable documentation for social historians and continues to enchant viewers with its depiction of a bygone era of Parisian glamour. He also provided illustrations for popular literary works, such as Alain-René Lesage's Gil Blas and Abbé Prévost's Manon Lescaut, further demonstrating his versatility.

Exile in England and British Connections

The political turmoil of the 1848 Revolution, which overthrew King Louis-Philippe and established the Second Republic, prompted Lami to leave France. Like many associated with the Orléans regime, he sought refuge in England, residing primarily in London from 1848 until 1852. This period of exile proved artistically fruitful.

In London, Lami found new patrons and subjects. He moved within aristocratic circles and gained access to the British court. He produced numerous watercolors depicting the life of Queen Victoria, Prince Albert, and their children, as well as scenes of London society and state occasions. These works showcase his adaptability, capturing the nuances of British court life and fashion with the same elegance he applied to Parisian scenes.

His time in England likely exposed him further to the British watercolor tradition and the works of prominent English artists like Sir Thomas Lawrence (though Lawrence had died in 1830, his influence persisted) and contemporaries. While Lami maintained his distinct French style, his English works demonstrate a continued engagement with the possibilities of watercolor and an ability to capture the specific atmosphere of his surroundings. His depictions of British royalty and society are held in high regard and form an important part of the Royal Collection Trust today. He returned to France following the establishment of the Second Empire under Napoleon III.

Later Career, Legacy, and Collections

Upon returning to France in 1852, Eugène Lami resumed his successful career, continuing to work prolifically for several more decades. He remained active well into his old age, producing watercolors, illustrations, and designs until shortly before his death in 1890 at the age of 90. His dedication to his craft was unwavering, and he maintained a high level of quality throughout his long career.

Lami's artistic achievements earned him considerable recognition during his lifetime and secured his place in the history of French art. His versatility allowed him to navigate different artistic currents and patronage systems across various political regimes. He was respected for his technical skill, his historical accuracy (particularly in military attire), and the sheer elegance and charm of his depictions of social life.

Today, Eugène Louis Lami's works are held in the collections of major museums around the world. These include the Louvre Museum and the Musée d'Orsay in Paris, the Château de Chantilly, the Victoria and Albert Museum and the British Museum in London, the Royal Collection Trust (UK), the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York, the Los Angeles County Museum of Art (LACMA), the Princeton University Art Museum, and the Louisiana State Museum, among others. This widespread institutional presence underscores his enduring importance and the continued appreciation for his art.

Artistic Style and Techniques Summarized

Eugène Lami's artistic identity is defined by its elegance, precision, and versatility across different media. His foundational academic training under Gros is evident in his strong draughtsmanship and compositional skills. However, his style evolved beyond strict Neoclassicism, incorporating Romantic sensibilities and a keen observation of contemporary life.

In lithography, particularly his military uniform series, his style is characterized by meticulous detail and accuracy, serving an almost documentary function while retaining artistic merit. He captured the texture and cut of fabrics, the gleam of metal, and the specific insignia of different regiments with remarkable fidelity.

His watercolors are perhaps his most distinctive contribution. Influenced by Bonington, he mastered transparent washes, delicate lines, and the subtle rendering of light and atmosphere. His palette was often refined, favoring harmonious color combinations that enhanced the elegance of his subjects, whether depicting intimate interiors, bustling social events, or historical scenes.

In his oil paintings, Lami demonstrated an ability to handle complex multi-figure compositions, particularly in his historical and battle scenes. While perhaps less revolutionary than contemporaries like Delacroix or Géricault (with whom he shared an interest in equestrian subjects), his paintings are marked by careful execution, narrative clarity, and often a focus on human drama within historical contexts. Throughout his work, a consistent thread is his attention to detail, particularly in costume and setting, which lends authenticity and charm to his diverse output.

Historical Significance and Influence

Eugène Louis Lami occupies a unique and significant position in 19th-century French art. He was not a radical innovator in the mold of the Impressionists who followed him, nor a dominant figure of a major school like Delacroix or Ingres. Instead, his importance lies in his versatility, his technical mastery across multiple media, and his role as a perceptive chronicler of his era.

He successfully bridged the gap between historical/military painting and the depiction of modern life, a transition many artists of his generation navigated. His early work documenting Napoleonic uniforms provided an invaluable historical record, while his later scenes of July Monarchy and Second Empire society offer a vivid window into the elite world of the time. His skill in watercolor helped elevate the medium's status in France.

His connections spanned the artistic and social spectrum, from his teachers Vernet and Gros, his peer Bonington, collaborators like Vernet, and associates like Géricault and the writer Alfred de Musset (for whom he provided illustrations), to his patrons among French and British royalty. He adeptly navigated the changing political landscape, finding favor under successive regimes. Lami's legacy is that of a consummate professional, a master craftsman whose elegant and detailed works captured the multifaceted spirit of 19th-century France, preserving its military history, social rituals, and fleeting fashions for posterity.