Introduction: A Mirror to Parisian Life

Paul Gavarni, whose real name was Guillaume-Sulpice Chevallier, stands as one of the most prolific and insightful illustrators of nineteenth-century France. Born in Paris on January 13, 1804, and passing away in the same city on November 24, 1866, Gavarni's life spanned a period of immense social and cultural transformation. He became renowned for his witty, elegant, and often satirical depictions of Parisian society, capturing its nuances, fashions, and follies with a keen eye and a masterful hand. Primarily working in lithography, his images filled the pages of popular journals, making him a household name and a key visual chronicler of his time.

While often compared to his contemporary, the formidable Honoré Daumier, Gavarni carved a distinct niche. Where Daumier wielded satire with political force and often focused on the struggles of the working class or the pomposity of the bourgeoisie, Gavarni’s observations were generally lighter, though no less perceptive. He excelled at portraying the world of entertainment, fashion, and the complex social interactions of the burgeoning urban landscape. His work offers an invaluable window into the everyday life, aspirations, and anxieties of Parisians during the July Monarchy and the Second Empire.

Early Life and the Birth of a Pseudonym

Guillaume-Sulpice Chevallier entered the world in humble circumstances in Paris. His family background was modest, necessitating that he seek practical employment early in life. Initially, he trained and worked as a precision instrument maker and later found employment in an engine factory. This technical background, perhaps surprisingly, may have honed his eye for detail and precision, qualities that would later manifest in his meticulous drawing style. Despite these practical beginnings, his artistic inclinations soon surfaced.

Lacking the means for formal academic training, Chevallier pursued his artistic education diligently, attending free drawing schools in Paris. He was largely self-taught, developing his skills through observation and practice. His early artistic endeavors included architectural and mechanical drawing, reflecting his initial training. However, his true calling lay in observing and sketching the human comedy unfolding around him in the vibrant streets and salons of Paris.

The adoption of his famous pseudonym, "Gavarni," is tied to a specific, somewhat amusing incident. Around 1829, he submitted a watercolour landscape drawing to the Paris Salon. The drawing depicted a scene from the Pyrenees, specifically the Cirque de Gavarnie. Due perhaps to a misunderstanding or clerical error, the work was catalogued as "Gavarni" after the location, implying it was the artist's name. Chevallier, possibly seeing the appeal of a more distinctive moniker, embraced the name, and Paul Gavarni the artist was born. This name would soon become synonymous with charming and insightful illustrations of French life.

Ascending the Parisian Art Scene

Gavarni's professional artistic career began to take shape in the late 1820s and early 1830s. He initially found work creating fashion plates and illustrations for journals like La Mode and the short-lived but elegant Journal des gens du monde. These early commissions helped him refine his elegant line and develop an understanding of contemporary style, which would remain a hallmark of his work even when applied to satirical subjects. His depictions of fashionable attire were sought after, showcasing his ability to capture the latest trends with grace and accuracy.

His major breakthrough, however, came with his contributions to satirical journals, most notably Le Charivari. Founded in 1832 by Charles Philipon, Le Charivari was a leading publication featuring caricatures and social commentary, famously employing Honoré Daumier as well. Gavarni began contributing regularly in the mid-1830s, and his work quickly gained immense popularity. His style, less overtly political than Daumier's but sharp in its social observation, resonated with the Parisian public.

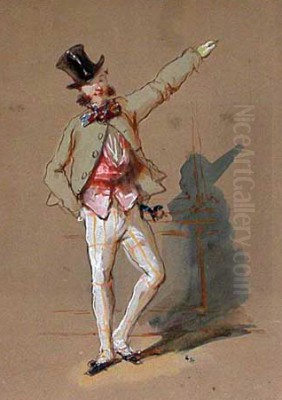

Gavarni's lithographs for Le Charivari and other publications like L'Artiste established his reputation. He developed recurring themes and character types drawn directly from the Parisian social landscape: students, artists, dancers, actors, the bourgeoisie, and particularly the figures inhabiting the demi-monde, such as the lorette (a type of kept woman or courtesan). His ability to capture the subtle interplay between characters, their expressions, and their fashionable surroundings made his work both entertaining and socially relevant. He became a celebrated figure, his name synonymous with the visual culture of Paris.

Artistic Style: Elegance, Wit, and Observation

Paul Gavarni developed a distinctive artistic style characterized by its elegance, fluidity, and keen observational detail. Working primarily in lithography, a medium he mastered, he utilized fine, often delicate lines to render figures and settings. His drawings possess a sense of movement and spontaneity, capturing gestures and expressions with remarkable vivacity. Unlike the sometimes harsh or sculptural forms found in Daumier's work, Gavarni's figures often retain a certain grace, even when depicted in moments of foolishness or moral ambiguity.

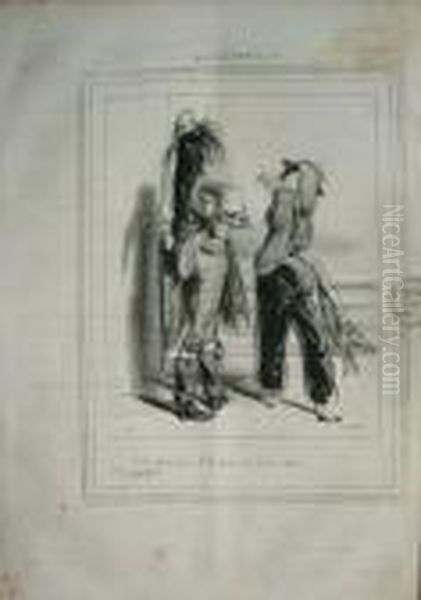

His satire was typically more subtle and less politically charged than that of Daumier or other contemporaries like J.J. Grandville. Gavarni focused on the comedy of manners, the nuances of social interaction, and the pervasive vanities and hypocrisies of urban life. He was less interested in overt political critique and more fascinated by the theatre of everyday existence – the flirtations, the social climbing, the domestic squabbles, the pursuit of pleasure and fashion. His captions, often written by himself, were integral to the works, adding another layer of wit and irony.

Gavarni possessed an exceptional ability to capture the specific atmosphere of different social milieux, from the rowdy student balls and carnival celebrations to the more restrained elegance of bourgeois salons. His understanding of fashion was profound, and his works serve as an important record of the changing styles of the period. Yet, beneath the surface charm, his work often carried a gentle critique of the superficiality and moral compromises he observed. He balanced amusement with a subtle melancholy, hinting at the fleeting nature of pleasure and the underlying anxieties of modern life. His contemporaries recognized this blend; the writer Charles Baudelaire, though critical at times, acknowledged Gavarni's skill in capturing the "modern."

Chronicling Parisian Types: Major Works and Series

Gavarni's vast output is often organized into series, each exploring a particular facet of Parisian society or a specific character type. These series, published in journals or as standalone albums, cemented his fame and showcased his thematic range. Among his most celebrated are Les Lorettes, which depicted the lives of young, fashionable kept women navigating the complexities of their social position. Gavarni portrayed them not simply as immoral figures but as complex individuals, often highlighting their wit, vulnerability, and the precariousness of their existence. This series was immensely popular, adding the term "lorette" to the common parlance.

Another notable series was Les Débardeurs, focusing on the costumes and characters found at Parisian masked balls, particularly the popular 'débardeur' (stevedore or docker) costume worn by both men and women. These images captured the boisterous energy and liberated atmosphere of the carnival. Similarly, Les Étudiants de Paris offered humorous insights into the lives, loves, and financial struggles of university students, a vibrant part of the Latin Quarter scene.

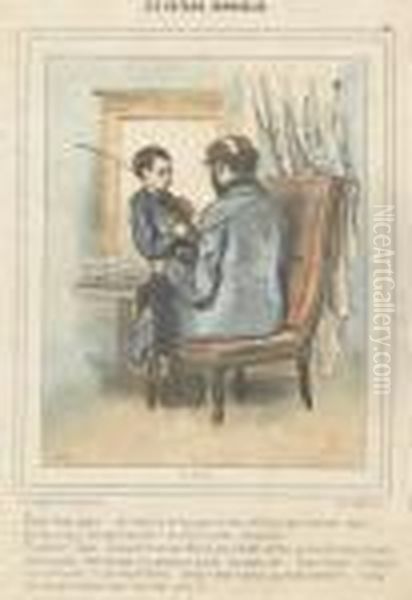

In Les Fourberies de femmes en matière de sentiment (Women's Deceptions in Matters of the Heart), Gavarni explored themes of romantic intrigue and manipulation with characteristic wit. He often depicted the subtle power dynamics between men and women in the game of love. Later in his career, particularly after his visit to London, his themes sometimes darkened, as seen in series like Les Enfants Terribles (Terrible Children) and Les Parents terribles (Terrible Parents), which cast a more critical eye on family life and its dysfunctions.

Perhaps one of his most intriguing creations was the recurring character Thomas Vireloque. Vireloque was depicted as a philosophical, somewhat cynical rag-picker, often clad in tattered finery. Through Vireloque, Gavarni offered more direct, sometimes biting commentary on society, poverty, and human nature. This character served as a kind of alter ego or mouthpiece for the artist's more somber reflections, standing apart from the lighter tone of much of his earlier work. The Goncourt brothers, his friends and biographers, considered Vireloque a significant, albeit less popular, aspect of his oeuvre.

The London Experience and a Shift in Perspective

In 1847, Gavarni embarked on a significant journey to London, staying for several years until 1851. This visit marked a turning point in his life and art. Invited initially to illustrate a periodical, he used the opportunity to observe English society, particularly the stark contrasts between wealth and poverty in the rapidly industrializing city. Unlike the often glamorous or amusing depictions of Parisian life, his London drawings took on a darker, more somber tone.

He was deeply affected by the poverty and squalor he witnessed in areas like St. Giles and Whitechapel. His series Gavarni in London (published 1849) presented a stark contrast to his Parisian scenes. The elegance and wit were largely replaced by depictions of hardship, gin addiction, ragged children, and the grim realities faced by the urban poor. Figures were often rendered with less grace and more emphasis on their suffering and degradation. This experience seemed to deepen his social conscience and introduced a more critical, less detached perspective into his work.

During his time in London, Gavarni also interacted with prominent British figures, including the novelists Charles Dickens and William Makepeace Thackeray, both keen observers of their own society. This exposure to a different cultural and social environment undoubtedly broadened his horizons. Upon his return to Paris, while he continued to produce work, there was a noticeable shift. His later series, such as Masques et Visages (Masks and Faces, 1857), continued to explore social themes but often with a greater sense of disillusionment or philosophical melancholy, perhaps influenced by his London observations and personal experiences.

Connections and Collaborations: A Man of His Time

Gavarni was deeply embedded in the artistic and literary circles of his time. His wit, charm, and professional success made him a welcome figure in Parisian society. His most significant relationship was perhaps with the Goncourt brothers, Edmond and Jules. They were close friends and admirers, and their detailed biography, Gavarni, l'homme et l'œuvre (Gavarni, the Man and the Work), published in 1873 after extensive interviews and access to the artist, remains a primary source for understanding his life and personality. Their book paints a portrait of a complex man – witty, observant, sometimes melancholic, and dedicated to his craft.

He was also acquainted with many leading writers. Honoré de Balzac, the great chronicler of French society in literature, admired Gavarni's visual acuity. Gavarni provided illustrations for some of Balzac's works, including Le Diable à Paris, and the two shared a mutual interest in dissecting the intricacies of contemporary life. Gavarni's circle likely included other prominent figures like Victor Hugo and Théophile Gautier, who also wrote about art and society. His connections extended to the publishing world, particularly through his long association with Charles Philipon and Le Charivari.

Among fellow artists, his name is inevitably linked with Honoré Daumier. Both were masters of lithography and key contributors to Le Charivari. While their styles and temperaments differed – Daumier more politically engaged and sculpturally powerful, Gavarni more focused on social manners and linear elegance – they represent the twin peaks of French caricature and social illustration in their era. Gavarni also worked alongside other illustrators like Cham (Amédée de Noé) and J.J. Grandville, each contributing to the rich visual commentary of the period. His work was also noted by later artists; James McNeill Whistler, for example, admired Gavarni's lithographs and was influenced by his elegant compositions and depictions of modern life. Artists like Edgar Degas and Édouard Manet, who also focused on scenes of modern Parisian life, would have been well aware of Gavarni's popular imagery.

Later Life, Watercolour, and Legacy

In the later stages of his career, particularly from the mid-1850s onwards, Gavarni's focus began to shift. While he continued to produce lithographs, including the notable series Masques et Visages (1857), he increasingly turned his attention towards watercolour. His watercolours often revisited themes from his earlier work but sometimes explored more personal or purely aesthetic concerns. Some critics felt these later works lacked the incisive energy of his prime years, perhaps reflecting a growing weariness or disillusionment.

A significant personal tragedy struck in 1857 with the death of his son, Jean. This loss deeply affected Gavarni, and according to the Goncourt brothers, he largely abandoned lithography and caricature after this point, finding it difficult to return to the often lighthearted or satirical tone that had defined much of his career. He retreated somewhat from the public eye, living a more secluded life in Auteuil, then a village on the outskirts of Paris.

Despite this withdrawal, his reputation remained considerable. He had produced an enormous body of work, estimated at around 8,000 pieces, primarily lithographs, which had shaped the way Parisians saw themselves and their city. When Paul Gavarni died on November 24, 1866, at the age of 62, he was mourned as a major figure in French art and illustration. His passing was noted widely, acknowledging his unique contribution to the visual culture of the nineteenth century.

Gavarni's legacy lies in his unparalleled role as a visual historian of Parisian manners and mores during a dynamic period. His work provides an intimate, witty, and often poignant glimpse into the lives of a diverse range of city dwellers. While sometimes overshadowed by the political force of Daumier, Gavarni's influence was significant, particularly in the realm of social illustration and the depiction of modern life. His elegant style, keen observation, and vast output ensure his place as a key interpreter of the human comedy as it played out on the boulevards, in the salons, and behind the closed doors of nineteenth-century Paris.

Art Historical Assessment: Chronicler of Manners

In the grand narrative of art history, Paul Gavarni is firmly established as a master of French nineteenth-century graphic art and a preeminent peintre de mœurs – a painter of manners. His contribution lies less in groundbreaking stylistic innovation in the manner of the Impressionists who followed, like Claude Monet or Pierre-Auguste Renoir, and more in his insightful and comprehensive documentation of his society through the medium of lithography. He captured the spirit of his age, particularly the July Monarchy and the Second Empire, with an unmatched blend of elegance and satirical wit.

His work is often evaluated in comparison to Honoré Daumier. While critics generally concede that Daumier possessed greater political depth and expressive power, Gavarni is praised for his subtlety, his refined technique, and his broader focus on the nuances of social behaviour, fashion, and the psychology of everyday interactions. He was, in many ways, the more 'Parisian' of the two, perfectly capturing the city's blend of sophistication, frivolity, and underlying tension. Artists like Constantin Guys, another chronicler of modern life admired by Baudelaire, operated in a similar vein, but Gavarni's reach through popular journals was arguably wider.

Gavarni's influence extended to fashion illustration and the development of caricature as a sophisticated art form. His ability to convey character and narrative through posture, expression, and attire set a high standard. Later artists interested in depicting contemporary urban life, from Whistler to Degas, would have found Gavarni's work a rich source of inspiration, even if their own styles diverged significantly. His creation of recognizable social types contributed to a shared visual understanding of the era.

Ultimately, Gavarni's importance rests on the sheer volume, quality, and perceptiveness of his work as a social commentator. He held up a mirror to Parisian society, reflecting its charms, its absurdities, and its complexities. His lithographs remain not only delightful works of art but also invaluable historical documents, offering enduring insights into the human condition as observed in the bustling, ever-changing landscape of nineteenth-century Paris.

Conclusion: An Enduring Vision of Paris

Paul Gavarni, born Guillaume-Sulpice Chevallier, remains an essential figure for understanding the visual culture and social fabric of nineteenth-century France. As a prolific lithographer, illustrator, and watercolourist, he captured the pulse of Parisian life with unparalleled elegance, wit, and observational acuity. From the fashionable salons to the student quarters, from the masked balls to the quiet anxieties of domestic life, Gavarni's art chronicled the manners, types, and transformations of his era. Though perhaps less politically pointed than some contemporaries like Daumier, his subtle satire and keen eye for human nature provided a unique and enduring commentary. His vast body of work continues to enchant viewers and offers invaluable insights into the vibrant, complex world of Paris during a pivotal century.