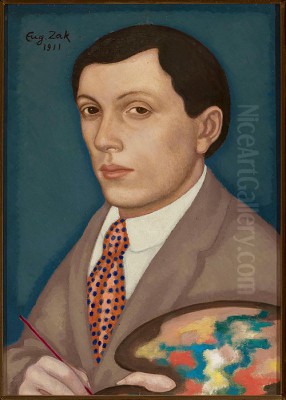

Eugeniusz Zak, also known as Eugeniusz Żak, stands as a significant yet sometimes overlooked figure in the vibrant tapestry of early 20th-century European art. A Polish-Jewish painter born in the twilight years of the 19th century, Zak navigated the complex artistic currents of his time, forging a unique path that blended classical traditions with modern sensibilities. His life, tragically cut short, was primarily centered in Paris, the undisputed capital of the art world, where he became a respected member of the diverse community known as the École de Paris (School of Paris). His work, characterized by a lyrical quality, idealized figures, and a subtle melancholy, continues to resonate with collectors and art historians today.

Early Life and Artistic Formation

Eugeniusz Zak was born in 1884 in Mogilno, a village within the Minsk Governorate of the Russian Empire, which is now part of modern-day Belarus. His background was Polish-Jewish, a heritage that would subtly inform his perspective throughout his life, although his art rarely engaged directly with overtly Jewish themes. His formative years were spent in Warsaw, Poland, where he received his initial education. Warsaw at the turn of the century was a city brimming with cultural and intellectual energy, providing a stimulating environment for a young aspiring artist.

Recognizing his artistic inclinations, Zak made the pivotal decision to move to Paris in 1902. This move placed him at the epicenter of artistic innovation. Paris was a magnet for artists from across Europe and beyond, fostering an atmosphere of intense creativity, experimentation, and exchange. Zak sought formal training, enrolling first at the prestigious École des Beaux-Arts, the traditional bastion of academic art education in France. He studied under the guidance of the renowned historical painter Jean-Léon Gérôme, absorbing the fundamentals of academic drawing and composition.

However, like many artists of his generation seeking more contemporary approaches, Zak also sought instruction outside the strictest confines of the academy. He joined the studio of Albert Besnard, a painter known for his more impressionistic and symbolist leanings. This exposure to different pedagogical methods and artistic philosophies was crucial in shaping Zak's developing style, allowing him to ground his work in solid technique while exploring more modern modes of expression. His time in Paris during these early years was marked by diligent study and immersion in the city's unparalleled artistic resources, from its museums to its burgeoning gallery scene.

Forging a Personal Style: Neoclassicism, Symbolism, and Beyond

Eugene Zak's artistic identity did not align neatly with any single dominant movement of his time, such as Fauvism or Cubism, although he was certainly aware of and influenced by them. Instead, he crafted a highly personal style that synthesized various influences into a coherent and recognizable aesthetic. A strong current of Neoclassicism runs through his work, evident in the clarity of line, the balanced compositions, and the often idealized, statuesque quality of his figures. This classical underpinning provided a sense of order and harmony to his canvases.

Simultaneously, Zak's art is deeply imbued with the spirit of Symbolism. His paintings often evoke a mood of quiet introspection, melancholy, or gentle nostalgia. The figures he portrays – fishermen, shepherds, musicians, dancers, or simply pensive individuals – seem to exist in an idyllic, timeless realm, detached from the harsh realities of modern life. They function less as specific portraits and more as archetypes or embodiments of certain emotional states or poetic ideas. This focus on mood and suggestion over literal representation connects him to the Symbolist tradition.

Zak also looked further back in art history for inspiration, demonstrating a particular affinity for the masters of the Italian Renaissance. Echoes of Leonardo da Vinci, for instance, can be discerned in the soft modeling (sfumato) of faces and the graceful, flowing lines he employed, particularly in his depictions of female figures. He admired the way Renaissance artists achieved a balance between naturalism and idealization. Furthermore, elements reminiscent of ancient Greek art, particularly in the sculptural quality and serene poses of his figures, contribute to the timeless, almost mythical atmosphere of his work.

The École de Paris and Artistic Milieu

Zak became an integral part of the École de Paris, a term used not to describe a specific style but rather the diverse community of foreign-born artists who converged on Paris, particularly in the Montparnasse district, during the first decades of the 20th century. This milieu was incredibly rich and varied, including artists like Amedeo Modigliani, Marc Chagall, Chaïm Soutine, Moïse Kisling, and Jules Pascin, among many others. While Zak's style differed significantly from the more expressionistic or avant-garde tendencies of some of his contemporaries, he shared with them the experience of being an expatriate artist contributing to the cosmopolitan culture of Paris.

He actively participated in the Parisian art scene, exhibiting his work regularly. He was accepted into the prestigious Salon d'Automne and the Salon des Indépendants, major annual exhibitions that showcased a wide range of contemporary art, from the established to the experimental. He was also a member of the Société des Artistes Français. These exhibitions provided crucial visibility and opportunities for critical reception and sales. His work gained recognition, attracting the attention of critics and collectors.

Zak maintained connections with fellow Polish artists living in Paris and Warsaw. He was a key figure in the founding of the Society of Polish Artists "Rhythm" (Towarzystwo Artystów Polskich "Rytm") in 1921. This group aimed to promote a modern Polish art that drew on national traditions while engaging with contemporary European trends, particularly Neoclassicism and Art Deco. Zak exhibited frequently with Rhythm in both Warsaw and Paris, often at venues like the Galerie La Licorne. His involvement with Rhythm underscores his commitment to fostering a modern Polish artistic identity within an international context.

His circle included interactions with other Polish artists active during this period, such as Roman Kramsztyk, another prominent Polish member of the École de Paris known for his portraits and landscapes. Zak also associated with figures like Kazimierz Stabrowski and Wacław Borowski, who were part of the Warsaw and Paris art scenes. The names Kazimierz Stachurski, Wacław Leopol, Godlewski, and Zygmunt Ty are also mentioned in connection with his Polish artistic interactions, reflecting a network of exchange and mutual support among expatriate and homeland artists. Earlier, around 1916, Zak had also been associated with the Formists (Formiści), a Polish avant-garde group exploring Cubist and Futurist ideas, though his own work remained more rooted in figurative traditions.

Beyond visual artists, Zak interacted with key figures in Parisian cultural life. The poet and art critic André Salmon, a champion of modern art and a friend to artists like Picasso and Modigliani, was among his acquaintances. Such connections were vital for artists, providing intellectual stimulation, critical support, and access to patrons and galleries. The mention of Adolf Basler (potentially misidentified as Adolf Salomon in some sources), another critic and dealer active in Montparnasse, further places Zak within the network of individuals shaping the Parisian art world. The reported connection to Robert Baden-Powell seems less direct and perhaps tangential to his core artistic circle.

Thematic Focus: Idealized Figures and Lyrical Landscapes

Zak's oeuvre is dominated by figurative painting, particularly portraits and depictions of solitary or grouped figures in idyllic settings. He had a distinct preference for certain character types: melancholic musicians, pensive shepherds, graceful dancers, and commedia dell'arte figures like Harlequin. These characters often appear detached from specific time or place, inhabiting a poetic, arcadian world conjured by the artist. They possess a gentle, introspective quality, rarely displaying strong emotion but rather conveying a sense of quiet contemplation or wistful longing.

His portrayal of the female figure is particularly noteworthy. Works like Female Portrait (created between 1911-1914) exemplify his approach. He tended to simplify and idealize his female subjects, emphasizing smooth contours, elegant postures, and serene expressions. These are not typically portraits in the conventional sense, aiming for a precise likeness, but rather explorations of feminine grace and beauty, imbued with a universal, timeless quality. His use of soft, harmonious colors and fluid lines contributes to their lyrical appeal. This approach shows his deep engagement with classical and Renaissance ideals of beauty, filtered through a modern sensibility.

While figures dominate his work, Zak also produced landscapes, often depicting scenes from his adopted city, Paris, and its surroundings. He painted views of the Seine, Parisian streets, and parks, capturing the unique atmosphere of the city. These landscapes, like his figure paintings, are often imbued with a poetic mood rather than strict topographical accuracy. He employed a refined sense of color and light to evoke particular times of day or emotional resonances. His travels, including visits back to Poland and time spent in southern France, also provided landscape motifs.

A significant work that encapsulates many aspects of his style is The Drummer of Manila (1924). This painting depicts a solitary, somewhat melancholic musician, rendered with Zak's characteristic smooth lines and idealized features. The title itself hints at an exoticism or imaginative element often present in his work. The painting achieved considerable recognition and serves as an example of the high regard in which his art was held, later fetching a significant price (€360,000) at auction, demonstrating the enduring market value of his major pieces.

Eastern Influences and Cross-Cultural Dialogue

A fascinating and somewhat unusual aspect of Eugene Zak's art is the discernible influence of East Asian aesthetics, particularly Japanese and Chinese art. This interest set him apart from many of his contemporaries whose engagement with non-Western art often focused on African or Oceanic forms (as seen in the work of Picasso or Modigliani). Zak seems to have been drawn to the subtlety, refinement, and compositional principles found in traditional East Asian painting.

Sources suggest he was particularly interested in Japanese art and possibly Chinese painting from the Song Dynasty, known for its delicate brushwork, atmospheric landscapes, and philosophical depth. The influence might be seen in his emphasis on line, his tendency towards flattened perspectives in some compositions, the harmonious integration of figures within their settings, and a certain elegance and decorative quality. This engagement with Eastern art added another layer to his synthesis of diverse traditions, contributing to the unique character of his work. In the context of early 20th-century Paris, where Japonisme had been influential decades earlier but was perhaps less central to the avant-garde discourse of the 1910s and 20s, Zak's sustained interest represented a distinct artistic path.

This cross-cultural dialogue, blending European traditions (Classical, Renaissance, Neoclassical, Symbolist) with elements inspired by East Asian art, highlights Zak's sophisticated and eclectic approach. He was not merely imitating styles but absorbing principles and integrating them into his own lyrical and harmonious vision. This ability to draw inspiration from diverse sources without sacrificing the coherence of his personal style is a testament to his artistic intelligence and sensitivity.

Recognition, Exhibitions, and the Shadow of History

Throughout his career, Eugene Zak achieved a notable level of recognition. His regular participation in the major Paris Salons brought his work to the attention of a wide audience. He exhibited not only in Paris but also internationally, with shows reported in cities like New York, London, and Munich. This indicates a growing reputation beyond the confines of the Parisian art scene. His work was appreciated for its technical skill, its poetic sensibility, and its unique blend of tradition and modernity.

A significant mark of esteem was the acquisition of his works by the French state for its national collections. Government purchases were an important form of validation and support for artists working in France. These acquisitions likely placed his work in what is now the Musée National d'Art Moderne at the Centre Pompidou, alongside other key figures of 20th-century art. His success extended to the commercial sphere as well, with his paintings finding buyers among discerning collectors, including prominent figures like the American collector Spencer Kellogg Jr.

However, Zak's legacy is also touched by the tragic events of the 20th century. One of his paintings, The Beggar, became entangled in the complex history of Nazi art looting during World War II. As a Polish-Jewish artist, Zak's work was deemed "degenerate" by the Nazi regime and was vulnerable to confiscation. The Beggar was stolen and eventually surfaced after the war. It was later identified and became the subject of restitution efforts. For many years, the painting was on long-term loan and display at the Mishkan Museum of Art in Ein Harod, Israel, before potentially being housed at the Israel Museum in Jerusalem. This specific case highlights the broader issue of art restitution and the enduring impact of historical trauma on cultural heritage, connecting Zak's personal story to a painful chapter of European history.

Later Years, Premature Death, and Legacy

Eugene Zak's artistic career was unfortunately brief. Despite achieving significant success and developing a mature and recognizable style, his life was cut short. He continued to work and exhibit actively in the early 1920s, dividing his time between Paris and visits to Poland, maintaining his connections with both artistic communities. He was a respected figure, known for his refined art and perhaps a reserved personality that mirrored the quiet introspection of his paintings.

In 1926, while in Paris, Eugene Zak died suddenly from a heart attack. He was only 41 years old. His premature death was a loss to the art world, silencing a unique voice that had successfully navigated the complex transition from 19th-century traditions to 20th-century modernism. He left behind a substantial body of work, but one can only speculate on how his art might have evolved had he lived longer, perhaps responding to the rise of Surrealism or other later movements.

Despite his early death, Zak's legacy endured. His widow, Jadwiga Kon-Zakowa, played a crucial role in preserving and promoting his reputation. In 1928, she founded the Galerie Zak in Paris. This gallery quickly became an important venue, not only showcasing Eugene Zak's work but also championing modern European and, significantly, Latin American artists in Paris. The Galerie Zak became a hub for cultural exchange, contributing actively to the Parisian art scene for several decades.

Eugene Zak's paintings continue to be held in high regard. His works are found in major museum collections, ensuring their accessibility to the public and their place in art historical narratives. Key institutions holding his art include the National Museum in Warsaw, which possesses a significant collection reflecting his importance in Polish art history; the Art Institute of Chicago; the Musée National d'Art Moderne (Centre Pompidou) in Paris representing the French state collections; and the Israel Museum in Jerusalem. His presence in these diverse international collections attests to his established reputation. Furthermore, his works remain sought after in the art market, appearing in auctions and private collections, indicating their continued aesthetic and commercial value. High-quality reproductions and prints also helped disseminate his imagery and maintain awareness of his distinctive style.

Historical Evaluation: A Bridge Between Worlds

Eugene Zak occupies a unique position in the history of early 20th-century art. He was undeniably modern, participating actively in the Parisian art world and associated with the progressive École de Paris. Yet, he consciously drew upon historical traditions, integrating elements of Neoclassicism, the Renaissance, and Symbolism into his work. He did not align himself with the radical formal experiments of Cubism (though he was aware of its impact) or the later provocations of Dada and Surrealism. Instead, he pursued a path centered on lyrical figuration, technical refinement, and poetic mood.

His art can be seen as a bridge – between Poland and Paris, between Jewish heritage and European culture, between classical tradition and modern sensibility, and even between Western and Eastern aesthetics. He synthesized these diverse elements into a harmonious and deeply personal vision. While sometimes perceived as standing slightly apart from the main avant-garde currents, his work offers a compelling alternative modernity, one rooted in continuity as much as rupture.

His contribution to Polish art is significant, representing a sophisticated engagement with international trends while retaining a distinct character. As a prominent member of the École de Paris, he demonstrated the vital role played by artists from Central and Eastern Europe in shaping the cosmopolitan culture of the French capital. His idealized, often melancholic figures continue to exert a quiet fascination, inviting viewers into a timeless, poetic world. Though his career was short, Eugene Zak left an indelible mark through his elegant, evocative, and masterfully executed paintings. His legacy is that of an artist who found a unique voice amidst the clamor of modernism, creating art of enduring beauty and quiet emotional depth.