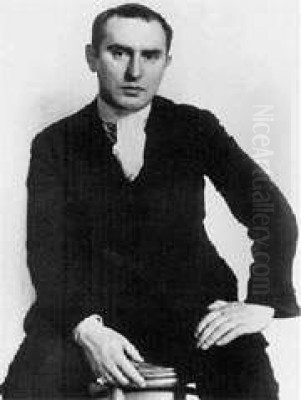

Jankel Adler stands as a significant yet often complex figure in the narrative of 20th-century European art. A Polish-Jewish artist whose life was irrevocably shaped by the tumultuous events of his time, Adler forged a unique visual language that synthesized major modernist currents with a deeply felt connection to his cultural heritage. His journey took him from the vibrant artistic circles of Poland and Weimar Germany to exile in France and finally to Great Britain, where he became an influential presence. His work, marked by its stylistic fusion, symbolic depth, and poignant reflection on the human condition, continues to resonate.

Early Life and Artistic Formation

Jankel Adler was born in 1895 in Tuszyn, a suburb of the industrial city of Łódź, Poland, then part of the Russian Empire. Born into a large Hasidic Jewish family, his upbringing immersed him in the rich traditions, mysticism, and visual culture of Eastern European Jewry, elements that would profoundly inform his later artistic output. Tuszyn itself was a multi-ethnic environment, providing early exposure to diverse cultural interactions.

His initial artistic training began not in painting but in engraving. Around 1912, he apprenticed with an uncle who was a goldsmith and engraver in Belgrade, Serbia. This early grounding in precise line work perhaps subtly influenced the strong structural quality found even in his more painterly works. Seeking broader artistic horizons, Adler moved to Germany. He studied at the Kunstgewerbeschule (School of Applied Arts) in Barmen, near Wuppertal, where he encountered modern German art movements.

Returning briefly to Poland around 1918-1920, Adler became involved with the burgeoning avant-garde scene in Łódź. He was a key member of "Jung Yiddish" (Young Yiddish), a group of Jewish writers and artists dedicated to creating modern art and literature rooted in Yiddish culture. This group, which included figures like the poet Moshe Broderzon and artists Marek Szwarc and Henryk Berlewi, sought to bridge traditional Jewish life with contemporary artistic expression, a goal Adler pursued throughout his career. His involvement solidified his commitment to exploring Jewish themes within a modernist framework.

The Düsseldorf Years and Weimar Vibrancy

In the early 1920s, Adler settled in Germany, drawn to the dynamic artistic environment of the Weimar Republic. He spent a significant period, from roughly 1922 to 1933, based primarily in Düsseldorf. This was a crucial phase in his development. He enrolled at the renowned Kunstakademie Düsseldorf (Düsseldorf Art Academy), a hub of artistic innovation.

It was here that Adler formed one of the most important relationships of his artistic life: a close friendship and professional association with Paul Klee. Klee began teaching at the Düsseldorf Academy in 1931, and the two artists shared a studio space and engaged in deep artistic dialogue. Klee's sophisticated understanding of colour theory, his interest in the spiritual and childlike in art, and his masterful linear quality undoubtedly influenced Adler. Conversely, Adler's robust forms and engagement with cultural identity may have offered points of interest for Klee.

During his Düsseldorf period, Adler was highly active in the progressive art scene. He associated with the "Das Junge Rheinland" (The Young Rhineland) group and later the "Rheinische Sezession." He also exhibited with the "Novembergruppe" in Berlin. His connections extended to other major figures associated with the Academy or the broader German avant-garde, including Otto Dix and Max Ernst, though his style remained distinct from theirs. He also maintained contact with members of the Cologne Progressives, such as Franz Seiwert and Otto Freundlich, artists committed to socially engaged, constructivist-influenced art.

Adler's work from this period shows a consolidation of influences. Elements of German Expressionism, particularly its emotional intensity and bold colour, merged with the structural innovations of Cubism, likely absorbed through reproductions or encounters with the work of artists like Pablo Picasso and Georges Braque. His paintings often featured figurative subjects – rabbis, families, figures from Jewish folklore – rendered with flattened perspectives, geometric simplification, and a rich, textured surface. In 1928, his growing reputation was acknowledged when he won a Gold Medal for his painting Cats at the "Deutsche Kunst Düsseldorf" exhibition.

Persecution and Exile

The rise of the Nazi Party brought Adler's flourishing career in Germany to an abrupt and brutal end. As a Jewish artist creating modern art, he was doubly targeted by the Nazi regime's cultural policies. In 1933, soon after Hitler came to power, Adler's work was declared "Entartete Kunst" (Degenerate Art). His paintings were systematically removed from German museums and public collections. Klee was also dismissed from his post at the Düsseldorf Academy that same year.

Facing increasing persecution and the impossibility of working freely, Adler fled Germany. He initially travelled, spending time in Paris, Poland, and other parts of Europe. Paris, a haven for many émigré artists, offered a temporary respite. There, he reconnected with artistic currents and reportedly deepened his acquaintance with Pablo Picasso, whose formal innovations continued to be a touchstone for Adler. He also likely encountered other exiled artists like Marc Chagall and Chaïm Soutine, fellow Jewish painters grappling with modernity and identity.

The infamous "Entartete Kunst" exhibition, staged by the Nazis in Munich in 1937 to ridicule and condemn modern art, included at least two of Adler's paintings, further cementing his status as an enemy of the regime's ideology. This public denunciation underscored the danger he faced. Throughout the 1930s, Adler remained committed to anti-fascist activities, using his art and connections to oppose the rising tide of totalitarianism.

The War Years and Arrival in Britain

With the outbreak of World War II in 1939 and the subsequent fall of France in 1940, Adler's situation became perilous once more. He managed to escape France, making his way to Great Britain. He initially arrived in Glasgow, Scotland, having enlisted in the Polish Army in exile. However, his service was short-lived; he was discharged in 1941 due to poor health (a heart condition).

Despite the hardships of exile and the anxieties of war, Adler continued to work. He found the artistic environment in Glasgow stimulating, connecting with local artists. His presence, along with that of other European émigrés like Josef Herman, brought a direct infusion of continental modernism to the Scottish art scene. He held an exhibition at T&R Annan & Sons gallery in Glasgow in 1942.

In 1943, Adler moved to London, which would be his base for the remainder of his life. He quickly became a significant figure in the London art world, particularly among the younger generation seeking alternatives to established British styles. His studio became a meeting place, and his sophisticated understanding of European modernism, combined with his powerful personality and the gravitas of his experiences, made him a compelling figure.

He exerted a notable influence on several British artists, most famously the Scottish painters Robert Colquhoun and Robert MacBryde (often referred to as "The Two Roberts"). They were deeply impressed by his technique, his use of colour and texture, and his ability to imbue figurative work with monumental, symbolic weight. Other artists associated with Neo-Romanticism and the post-war London scene, such as Keith Vaughan and Prunella Clough, also likely absorbed aspects of his approach. Adler exhibited regularly at prominent London galleries like the Redfern Gallery, the Lefevre Gallery, and Gimpel Fils.

It was during the post-war period that Adler received the devastating news that his nine siblings and their families had perished in the Holocaust in Poland. This unimaginable personal tragedy cast a long shadow over his final years and inevitably permeated the mood of his later work, lending it a profound sense of loss and elegy, even when not overtly addressing the subject.

Artistic Style, Techniques, and Symbolic Language

Jankel Adler's art is characterized by its synthesis of diverse stylistic elements and its rich symbolic content. He never adhered strictly to a single movement but instead forged a personal idiom that drew from Expressionism, Cubism, and Surrealism, all filtered through his unique cultural lens.

Stylistic Fusion: His early work showed Expressionist tendencies in its emotive force and bold execution. The influence of Cubism, particularly the analytical approach of Picasso and Braque, and the synthetic compositions of Fernand Léger, became increasingly evident in his handling of form and space. He fragmented figures and objects, flattened perspective, and built compositions through interlocking planes of colour. However, unlike purely formal Cubism, Adler's work always retained a strong emotional and symbolic core. His encounter with Klee reinforced an interest in line, texture, and the evocative power of colour.

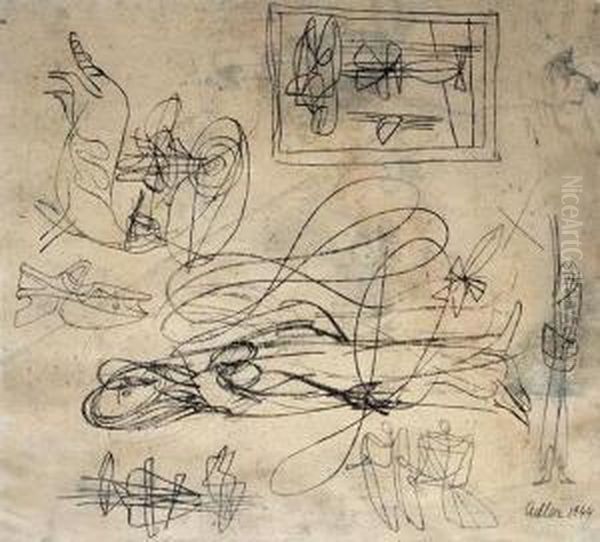

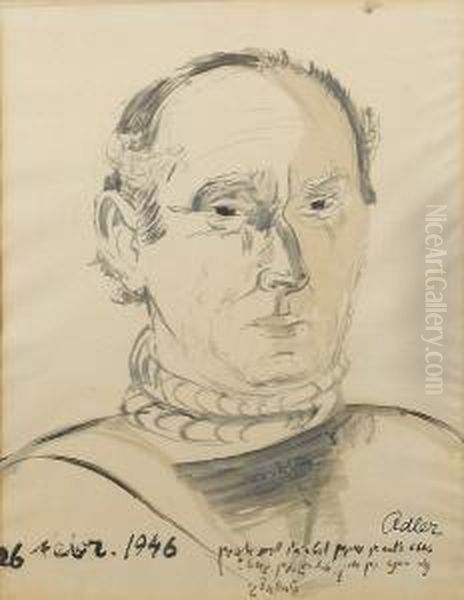

Techniques: Adler was a versatile technician. He worked primarily in oil paint but often incorporated other materials and techniques to achieve complex surfaces. He frequently used sand mixed with paint to create thick impasto and textured grounds. Sgraffito – scratching through layers of paint to reveal underlying colours – was another characteristic technique, adding linear definition and surface complexity. His background in engraving perhaps contributed to the strong, almost incised quality of line often found in his paintings. He also produced prints and drawings throughout his career.

Colour and Form: Adler's palette was often rich and sonorous, employing deep reds, blues, ochres, and blacks, frequently juxtaposed for dramatic effect. His forms, while often simplified and stylized, possess a distinct solidity and monumentality. Figures tend to be hieratic, frontal, and imbued with a sense of timelessness, recalling ancient frescoes or Byzantine icons as much as modernist fragmentation.

Symbolic System: Jewish themes are central to Adler's oeuvre. He depicted rabbis, scholars, biblical scenes (like King David), and motifs drawn from Hasidic folklore and mysticism. These were not mere illustrations but explorations of cultural identity, spirituality, and the endurance of tradition in the modern world. Hebrew letters sometimes appear as compositional elements. Beyond specific Jewish iconography, his work often carries broader symbolic weight, addressing universal themes of suffering, resilience, human connection, and alienation. Figures often have large, expressive eyes that convey deep emotion or introspection. Animals, particularly birds and cats, appear frequently, sometimes as domestic companions, other times carrying symbolic connotations of freedom, fate, or the uncanny. His later works, created under the shadow of war and personal loss, often possess a more somber, elegiac quality, with figures appearing isolated or fragmented, reflecting the traumas of the era. Representative works illustrating these aspects include Two Rabbis, King David, Cats (1928), No Man's Land (c. 1942), Woman with Cat (c. 1945), and numerous powerful self-portraits.

Relationships and Influence

Adler's position within the network of 20th-century artists was complex, defined by both collaboration and the inherent competition of the art world, exacerbated by political persecution.

His most significant collaborative relationship was undoubtedly with Paul Klee in Düsseldorf. This was a friendship built on mutual respect and shared artistic exploration. While Klee was the more established figure, their interaction appears to have been a genuine dialogue.

His involvement with groups like "Jung Yiddish" and "Das Junge Rheinland" demonstrates his belief in collective artistic endeavour and shared cultural goals. In Paris, his friendship with Picasso placed him in proximity to the epicenter of modern art, absorbing influences while maintaining his distinct voice.

The Nazi persecution cast him in an oppositional role, placing his work in direct conflict with state-sanctioned art. This experience of marginalization and exile profoundly shaped his perspective and artistic themes.

In Britain, Adler transitioned from being primarily influenced by others to becoming an influential figure himself. His impact on Colquhoun, MacBryde, and potentially others was significant, helping to transmit continental European ideas about form, colour, and expressive figuration into the British art scene at a crucial moment. While he is not known to have had formal students in an academic sense, his role as a mentor and source of inspiration for younger artists in London was undeniable. He served as a living link to the pre-war European avant-garde.

Legacy

Jankel Adler died relatively young, in 1949, at the age of 54, in Aldbourne, Wiltshire, where he had settled shortly before his death. His passing occurred just as post-war artistic life was fully resuming and his influence in Britain was solidifying.

His legacy is multifaceted. He is recognized as a key figure of the École de Paris, particularly among those artists whose careers were disrupted by Nazism. He represents the vital contribution of émigré artists to the cultural life of their host countries, in his case, Great Britain. His work serves as a powerful testament to the fusion of Jewish identity and modernist aesthetics, standing alongside figures like Chagall and Soutine in exploring this complex terrain.

Adler's art provides a poignant visual record of the anxieties, traumas, and resilience of the 20th century. His unique synthesis of Expressionist feeling, Cubist structure, and symbolic depth, rooted in his personal history and cultural heritage, ensures his enduring place in the history of modern art. Although perhaps not as widely known as some of his contemporaries like Picasso or Klee, his work continues to be exhibited and studied, recognized for its artistic quality, historical significance, and profound humanism. He remains a vital bridge between the artistic worlds of Eastern Europe, Germany, and Great Britain.