William Clarke Wontner (1857-1930) stands as a significant, if sometimes overlooked, figure in the landscape of late Victorian and early Edwardian British art. A painter renowned for his exquisitely rendered female figures, often draped in classical or "Oriental" attire and set against meticulously detailed backdrops, Wontner carved a distinct niche for himself. His work, deeply embedded in the Neoclassical and Orientalist trends of his time, offers a fascinating window into the aesthetic sensibilities and cultural preoccupations of an era teetering on the brink of modernism. This exploration will delve into his life, artistic development, stylistic characteristics, key influences, notable works, and his place within the broader art historical context.

Early Life and Artistic Foundations

William Clarke Wontner was born in Stockwell, Surrey, London, on January 17, 1857. His artistic inclinations were nurtured from a young age, as he hailed from a family with strong connections to the arts. His father, William Hoff Wontner (c.1814-1881), was a respected architect, designer, and decorative painter. This familial environment undoubtedly provided the young Wontner with early exposure to design principles, draughtsmanship, and the broader world of artistic creation. It's plausible that his father's work in architectural rendering and decorative schemes instilled in him an appreciation for precision, detail, and harmonious composition – qualities that would later define his mature style.

His formal artistic training commenced at the St. John's Wood Art School, a notable institution in London that served as a preparatory school for many aspiring artists aiming for the prestigious Royal Academy Schools. The St. John's Wood Art School, founded by A. A. Cary in 1878 (though its roots go back further with earlier iterations like "Leigh's"), was known for its rigorous academic approach, emphasizing life drawing and anatomical correctness. This foundational training was crucial for artists like Wontner who specialized in figurative work. It was here, or through connections made via his father and the school, that he likely began to associate with other artists who would share similar aesthetic leanings.

The Victorian Art World: Neoclassicism and the Allure of the Orient

To fully appreciate Wontner's artistic trajectory, it's essential to understand the prevailing currents in the British art world during the latter half of the 19th century. The Royal Academy of Arts held considerable sway, championing academic painting that often drew upon historical, mythological, or literary themes. Within this academic tradition, Neoclassicism experienced a significant revival, often referred to as Victorian Neoclassicism or the Olympian Dream.

Artists like Lord Frederic Leighton (1830-1896), Sir Edward Poynter (1836-1919), and Albert Moore (1841-1893) were leading proponents of this movement. They sought to evoke the perceived purity, harmony, and idealized beauty of classical antiquity, particularly Greece and Rome. Their works often featured languid figures in classical drapery, set within archaeologically informed architectural settings. This movement was, in part, a reaction against the perceived sentimentality of earlier Victorian genre painting and the moralizing intensity of the Pre-Raphaelites, though it shared with the latter a commitment to meticulous detail.

Concurrent with this classical revival was the pervasive fascination with "the Orient" – a term then used broadly to encompass North Africa, the Middle East, and sometimes even parts of Asia. Orientalism in art, fueled by colonial expansion, increased travel, and popular literature, offered artists a rich tapestry of exotic subjects, vibrant colors, and sensual themes. Painters like Jean-Léon Gérôme (1824-1904) in France, and John Frederick Lewis (1804-1876) and Frederick Arthur Bridgman (1847-1928) in Britain and America, respectively, captivated audiences with their depictions of bustling souks, opulent harems, and dramatic desert landscapes. While often romanticized and sometimes based on stereotypical Western perceptions, these works catered to a public eager for escapism and the allure of the unknown.

Wontner's Stylistic Development and Key Influences

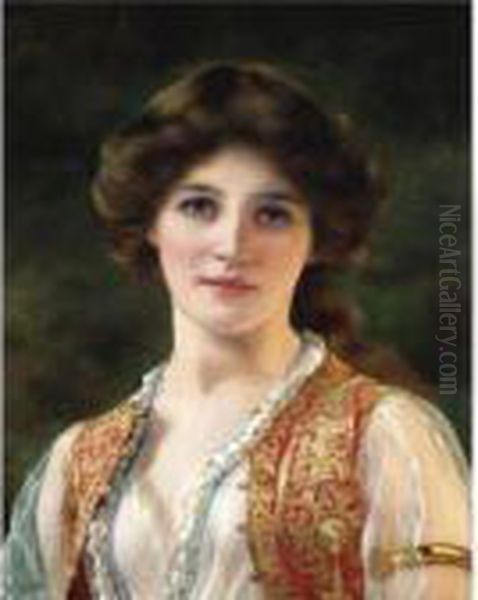

William Clarke Wontner's art skillfully navigated the confluence of these Neoclassical and Orientalist streams. His primary focus was the female figure, rendered with a smooth, almost porcelain-like finish. These women, typically fair-skinned and possessing a serene, often melancholic beauty, became the hallmark of his oeuvre. He excelled in capturing the subtle play of light on fabric and flesh, imbuing his subjects with a tangible, yet idealized, presence.

A pivotal influence on Wontner, and indeed on a generation of artists pursuing similar themes, was Sir Lawrence Alma-Tadema (1836-1912). A Dutch-born painter who settled in England, Alma-Tadema became phenomenally successful with his meticulously researched and brilliantly executed scenes of everyday life in ancient Rome, Greece, and Egypt. His "marbellous" paintings, so-called for his virtuoso rendering of marble textures, set a standard for archaeological accuracy and sensuous beauty. Wontner, like many of his contemporaries, clearly absorbed Alma-Tadema's dedication to detail, his luminous palette, and his ability to make the classical past feel both grand and intimately accessible.

Wontner's particular brand of Neoclassicism often leaned towards the more decorative and less narrative aspects of the style. While his figures might wear classical robes or be surrounded by classical props like marble columns or urns, the emphasis was less on storytelling and more on creating an atmosphere of timeless beauty and quiet contemplation. His women are often depicted in moments of repose, gazing thoughtfully into the distance or engaging in gentle activities.

The Orientalist Strain in Wontner's Art

The Orientalist elements in Wontner's work are equally prominent. He frequently adorned his models with exotic jewelry, elaborate headdresses, and richly patterned fabrics that evoked Middle Eastern or North African aesthetics. Backgrounds might feature Islamic-style architectural details, patterned tiles, or glimpses of lush, tropical foliage. However, it's important to note that Wontner, like many of his British contemporaries, rarely, if ever, traveled to the regions he depicted. His Orientalism was largely a studio-based construct, drawing upon available props, textiles, and existing visual tropes.

His "Oriental" women were almost invariably Caucasian, a common practice among Western Orientalist painters. This approach, while catering to the tastes of his clientele, raises complex questions about cultural appropriation and the Western gaze, issues that have been extensively explored by scholars like Edward Said. For Wontner and his audience, these exotic trappings likely served to enhance the sensuality and allure of the female figure, transporting her from the mundane reality of Victorian England to a realm of fantasy and romance. The combination of classical features with Eastern attire created a hybrid beauty that was particularly appealing.

Friendship and Artistic Kinship with John William Godward

One of the most significant personal and professional relationships in Wontner's life was his close friendship with fellow painter John William Godward (1861-1922). Godward was another prominent figure in the late Neoclassical movement, also heavily influenced by Alma-Tadema. Both artists shared a studio for a period, and their styles exhibit considerable similarities: a focus on idealized female beauty, meticulous attention to detail (especially in rendering fabrics and marble), and a preference for classical or vaguely exotic settings.

Their shared artistic journey is evident in the thematic and stylistic parallels in their work. Both Wontner and Godward specialized in what could be termed "drawing-room Neoclassicism" – paintings that were aesthetically pleasing, technically accomplished, and perfectly suited for the homes of affluent Victorian and Edwardian collectors. They often depicted solitary female figures, lost in reverie, embodying a sense of tranquil beauty. While Godward perhaps leaned more consistently towards purely Greco-Roman settings, Wontner more frequently incorporated Orientalist elements.

The story of Godward's later life is a tragic one; disillusioned with the decline in popularity of his style in the face of rising Modernism, he committed suicide in 1922. Wontner, however, continued to paint and exhibit, adapting, to some extent, to changing tastes, though his core style remained rooted in the academic traditions of his youth.

Notable Works and Their Characteristics

Wontner's body of work is characterized by a consistent level of technical skill and a recurring set of thematic concerns. While many of his paintings are now in private collections, several titles are frequently cited as representative of his style.

_An Eastern Beauty_ and _An Elegant Beauty_: These titles, or variations thereof, appear frequently in relation to Wontner's work and encapsulate his primary subject matter. Such paintings typically feature a single female figure, exquisitely dressed, often with a thoughtful or demure expression. The focus is on the delicate rendering of her features, the richness of her attire, and the harmonious composition.

_Safie, One of the Three Ladies of Baghdad_ (circa 1900): This title explicitly references the Arabian Nights, a popular source of inspiration for Orientalist artists. The painting would likely depict a woman in elaborate Middle Eastern-inspired costume, embodying the romanticized vision of the "Orient" prevalent at the time. The attention to textile patterns, jewelry, and perhaps a suggestive setting would be characteristic.

_The Turban_ (circa 1920): This later work indicates Wontner's continued engagement with Orientalist themes well into the 20th century. The turban itself is a potent symbol of the East, and the painting would likely focus on the interplay of the fabric's folds and colors with the model's features. It demonstrates the enduring appeal of these subjects for both the artist and his patrons.

Other works often feature titles that evoke a sense of exoticism or classical reverie, such as A Persian Princess, The Odalisque, or At the Well. In all these paintings, Wontner's meticulous technique is paramount. He paid close attention to the textures of silk, velvet, and muslin, the gleam of gold and jewels, and the softness of skin. His color palettes were often rich and harmonious, employing deep reds, blues, and golds, contrasted with creamy whites and delicate pastels.

Exhibitions, Reception, and Patronage

William Clarke Wontner was a regular exhibitor at prominent London venues. He began showing his work at the Royal Academy in 1879, a significant milestone for any aspiring artist. He also exhibited at the Royal Society of British Artists (RBA) and the Royal Institute of Painters in Water Colours (RI). When the Grosvenor Gallery, a more progressive alternative to the Royal Academy, closed in 1890, Wontner, like many artists who had shown there, transitioned to exhibiting at the New Gallery.

His work was generally well-received within its sphere. The technical polish, appealing subject matter, and decorative qualities of his paintings found favor with a segment of the art-buying public that appreciated academic skill and romantic themes. These collectors were often newly wealthy industrialists and middle-class professionals who sought art that was both beautiful and indicative of cultural refinement. Wontner's paintings, with their air of languid elegance and exotic charm, fit perfectly into the opulent interiors of late Victorian and Edwardian homes.

However, by the early 20th century, the artistic landscape was undergoing a radical transformation. The rise of Impressionism, Post-Impressionism, Fauvism, and Cubism began to shift critical and public attention away from academic and Neoclassical art. Artists like Claude Monet (1840-1926), Vincent van Gogh (1853-1890), Paul Cézanne (1839-1906), Henri Matisse (1869-1954), and Pablo Picasso (1881-1973) were forging new visual languages that challenged traditional notions of representation and beauty. In this rapidly changing environment, the meticulously crafted, idealized visions of Wontner and his contemporaries began to seem increasingly old-fashioned to the avant-garde.

Personal Life and Later Years

Details about Wontner's personal life beyond his artistic career are somewhat scarce, a common situation for artists who did not achieve the very highest echelons of fame or who were not subjects of extensive contemporary biography. We know he married Jessie Marguerite Keene (1872-1950) on June 7, 1894, in Kensington, London. Jessie was the daughter of the artist Charles Joseph Keene. The couple reportedly had no children.

Wontner continued to paint throughout the early decades of the 20th century, maintaining his characteristic style even as artistic fashions moved decisively in other directions. He passed away on September 23, 1930, in Worcester Park, Surrey, at the age of 73. He was buried in the churchyard of St. John the Baptist in Ripple, Worcestershire, a picturesque village that perhaps appealed to his sense of traditional beauty.

Wontner's Legacy and Art Historical Standing

For much of the 20th century, William Clarke Wontner, like many academic painters of his generation, was largely relegated to the footnotes of art history. The dominant narrative, shaped by proponents of Modernism, tended to dismiss Victorian academic art as sentimental, overly literary, or simply irrelevant to the progressive trajectory of art. Artists like Alma-Tadema, Leighton, Poynter, Godward, and Wontner were often seen as representing a bygone era, their meticulous realism and classical themes out of step with the spirit of the modern age.

However, in recent decades, there has been a significant scholarly and curatorial re-evaluation of 19th-century academic art. Art historians have begun to look beyond the modernist bias and appreciate these artists on their own terms, recognizing their technical skill, their engagement with important cultural themes, and their considerable contemporary popularity. Wontner's work is part of this broader reassessment.

His paintings are now sought after by collectors of Victorian art, and they appear periodically at auction, often commanding respectable prices. While he may not have been an innovator in the mold of the Impressionists or the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood (figures like Dante Gabriel Rossetti or John Everett Millais), Wontner was a highly skilled practitioner within his chosen genre. He successfully synthesized elements of Neoclassicism and Orientalism to create a distinctive body of work characterized by its elegance, sensuality, and meticulous craftsmanship.

His art offers valuable insights into the tastes and aspirations of his time. The fascination with idealized female beauty, the romantic allure of distant lands and ancient civilizations, and the desire for art that was both aesthetically pleasing and technically accomplished – all these aspects of late Victorian and Edwardian culture are reflected in Wontner's paintings. He can be seen as a master of a particular kind of escapist art, offering his viewers a glimpse into worlds of serene beauty and exotic enchantment, far removed from the industrial realities and social upheavals of his day.

Conclusion: An Enduring Appeal

William Clarke Wontner's contribution to British art lies in his consistent production of beautifully crafted paintings that catered to a specific, yet significant, taste for Neoclassical elegance and Orientalist fantasy. He was a consummate professional, a skilled draughtsman, and a sensitive colorist who excelled in the depiction of the female form. His close association with John William Godward and their shared reverence for the style of Lawrence Alma-Tadema place him firmly within a distinct school of late Victorian classicism.

While the grand narratives of art history have often favored the revolutionary and the avant-garde, there is enduring value and interest in the work of artists like Wontner who perfected and perpetuated established traditions. His paintings, with their languid beauties, rich textiles, and evocative settings, continue to charm and captivate viewers, offering a seductive escape into a world of idealized grace. As an art historian, one recognizes Wontner not as a radical innovator, but as a talented and dedicated artist who masterfully captured a particular aesthetic ideal, leaving behind a legacy of exquisitely rendered visions that speak to the enduring human fascination with beauty, romance, and the allure of the exotic. His work remains a testament to a specific moment in art history when classical ideals and Oriental dreams converged on the canvases of British painters.