Évariste Vital Luminais, a prominent figure in 19th-century French academic painting, carved a unique niche for himself as the "painter of the Gauls." Born into an era of burgeoning national identity and historical inquiry, Luminais dedicated much of his artistic output to vividly reconstructing scenes from France's earliest history, particularly the lives of the Gallic tribes and the tumultuous era of the Merovingian dynasty. His work, characterized by dramatic compositions, meticulous detail, and a romantic sensibility, captured the imagination of his contemporaries and continues to offer a fascinating window into how the past was perceived and portrayed during his time. While firmly rooted in the academic tradition, Luminais's powerful narratives and evocative atmospheres set him apart, earning him both critical acclaim and popular recognition.

Early Life and Artistic Formation in Nantes and Paris

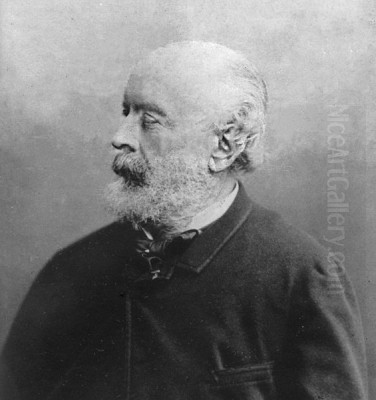

Évariste Vital Luminais was born on October 13, 1821, in Nantes, a historically rich city in western France. His family background was one of law and order; his father served as a parliamentary official, a position that might have suggested a different career path for young Évariste. However, his innate artistic talent was undeniable from an early age. Recognizing his son's passion and potential, Luminais's family made the pivotal decision to support his artistic aspirations.

At the age of eighteen, around 1839, Luminais was sent to Paris, the undisputed epicenter of the European art world. This move was crucial for any aspiring artist seeking formal training and exposure to the masters. In Paris, he embarked on his artistic education under the tutelage of several respected figures. Among his first teachers was Auguste Debay de La Subverie (often cited as Auguste de Bassins-Cadet), a painter and sculptor who could have provided a foundational understanding of form and composition.

More significantly, Luminais studied with Léon Cogniet, a highly regarded historical and portrait painter. Cogniet, a winner of the prestigious Prix de Rome, was known for his dramatic historical scenes, such as Tintoretto Painting His Dead Daughter (1843), and his portraits that captured the sitter's character. Under Cogniet, Luminais would have honed his skills in narrative composition, anatomical accuracy, and the grand manner of historical painting that was highly valued by the French Académie des Beaux-Arts.

Another influential teacher was Constant Troyon. Troyon was a leading figure of the Barbizon School, renowned for his naturalistic landscapes and, particularly, his depictions of animals, especially cattle. While Luminais would become known for historical human dramas, Troyon's emphasis on keen observation of nature, the play of light, and atmospheric effects likely contributed to the evocative settings Luminais would later create for his historical narratives. The Barbizon painters, including Jean-Baptiste-Camille Corot and Jean-François Millet, sought a more direct and unidealized representation of the French countryside, a departure from the classical landscapes of artists like Nicolas Poussin. Troyon's influence might be seen in the rugged, often untamed landscapes that serve as backdrops in Luminais's Gallic scenes.

This combination of teachers – Cogniet for historical drama and Troyon for naturalistic observation – provided Luminais with a versatile skill set, blending academic rigor with a sensitivity to atmosphere and environment.

The Paris Salon and Academic Success

The Paris Salon, the official art exhibition of the Académie des Beaux-Arts, was the primary avenue for artists to gain recognition, attract patrons, and establish their careers in 19th-century France. Luminais made his debut at the Salon in 1843, marking his formal entry into the competitive Parisian art scene. His early submissions likely focused on genre scenes and historical subjects, gradually building his reputation.

Luminais quickly established himself as a competent and engaging painter within the academic tradition. His works were regularly accepted at the Salon, and he began to receive accolades for his skill and thematic choices. He was awarded medals at the Salon on several occasions, including in 1852, 1855, 1857, and 1861, signifying the approval of the Salon jury and enhancing his standing. These awards were critical for an artist's career, leading to commissions, sales, and greater public visibility.

His style was characterized by strong drawing, careful attention to historical detail (as understood in his time), dramatic lighting, and a flair for storytelling. He focused primarily on genre scenes – depictions of everyday life, often with a historical flavor – and more ambitious historical paintings. His particular fascination with the early history of France, especially the Merovingian period (roughly 5th to 8th centuries) and the pre-Roman Gauls, began to define his oeuvre and distinguish him from many of his contemporaries who might have favored classical antiquity or more recent French history. Artists like Jean-Léon Gérôme, for instance, often explored classical Roman or Orientalist themes with meticulous detail, while William-Adolphe Bouguereau and Alexandre Cabanel excelled in mythological and allegorical subjects, often with a highly polished, idealized finish. Luminais, by contrast, delved into the "barbaric" and often violent past of his own nation.

The culmination of his official recognition came in 1869 when he was made a Chevalier of the Legion of Honour, one of France's highest civilian awards. This honor solidified his status as a respected member of the French artistic establishment. He would later receive a gold medal at the Exposition Universelle of 1889 in Paris, a further testament to his enduring reputation.

The "Painter of the Gauls": Themes and Subjects

Luminais earned the evocative sobriquet "le peintre des Gaules" (the painter of the Gauls) due to his profound and sustained engagement with the imagery of the ancient Gallic peoples who inhabited France before the Roman conquest. This thematic focus resonated deeply within the context of 19th-century France, a period marked by a fervent search for national origins and a desire to construct a cohesive national identity. The Gauls, particularly figures like Vercingetorix, were being re-evaluated and celebrated as symbols of French resistance and primordial national spirit, a narrative that gained traction after the Franco-Prussian War of 1870-71.

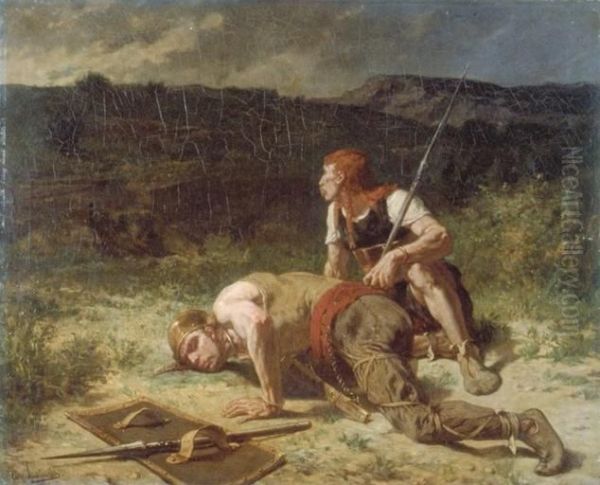

Luminais's depictions of the Gauls were often dramatic and imbued with a sense of raw, untamed energy. He portrayed them as fierce warriors, hardy hunters, and people deeply connected to the rugged landscapes they inhabited. Works like Gallic Vedette (Scouts) or The Defeat of the Cimbri and Teutons by Marius showcase his interest in their martial prowess and their confrontations with Rome. He did not shy away from the brutality of the era, often depicting scenes of conflict, flight, or desperate survival. His Gauls were not the idealized "noble savages" of an earlier era but rather robust, often grim figures, reflecting a more romanticized yet gritty vision of the past.

Beyond the Gauls, Luminais was equally captivated by the Merovingian dynasty, the Frankish kings who ruled after the fall of the Western Roman Empire. This was a period of legendary figures, internecine conflict, and the gradual Christianization of Francia. His paintings often explored the dramatic and often tragic tales from this era, drawing on chronicles like those of Gregory of Tours. He depicted scenes of royal intrigue, brutal power struggles, and moments of intense human suffering. These subjects allowed him to explore themes of loyalty, betrayal, vengeance, and faith, all set against the backdrop of a formative period in French history.

One notable work, The Flight of King Gradlon (La Fuite du roi Gradlon), draws from Breton legend, depicting the mythical king of Ys escaping the submerged city with his daughter Dahut, who, according to legend, caused its destruction. This painting, like many others, highlights Luminais's interest in regional folklore and the often-dark tales that formed part of France's diverse cultural heritage. His painting Les Merovingiens (The Merovingians), depicting a group of horsemen, possibly warriors or a royal retinue, navigating a swampy, desolate landscape, evokes the harsh realities and perilous journeys of the era.

Luminais's commitment to these early historical themes was distinctive. While other historical painters like Paul Delaroche focused on later, often English or French royal history with a highly polished, almost theatrical style, Luminais delved into a more remote and "primitive" past, bringing it to life with a vigorous, if sometimes romanticized, realism.

Masterpieces and Signature Works

While Luminais produced a substantial body of work, a few paintings stand out as his masterpieces, defining his legacy and encapsulating his artistic vision.

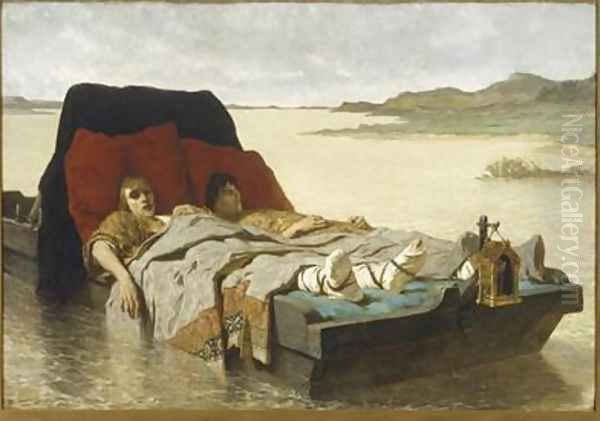

_The Sons of Clovis II_ (Les Énervés de Jumièges)

Arguably his most famous and impactful work is The Sons of Clovis II, also known as Les Énervés de Jumièges (The Enervated Ones of Jumièges). Exhibited at the Paris Salon of 1880, this painting caused a sensation and remains an iconic image of Merovingian drama. The painting depicts a harrowing scene based on a medieval legend. According to the story, the two sons of King Clovis II and Queen Bathilde rebelled against their father. As punishment, they were "enervated" – their tendons severed, rendering them powerless – and set adrift on a raft on the River Seine, left to the mercy of fate.

Luminais masterfully captures the tragic plight of the two young princes. They lie on a richly adorned funerary barge, seemingly unconscious or near death, their pale, languid bodies contrasting with the opulent fabrics. A single taper burns at their head, symbolizing their fading lives and perhaps a vigil. The raft drifts silently on the dark, misty waters of the Seine, conveying a profound sense of desolation, abandonment, and impending doom. The composition is stark and emotionally charged. The story concludes with the monks of Jumièges Abbey discovering and rescuing the princes, who then devote their lives to the monastery.

The painting was lauded for its dramatic intensity, its skillful rendering of textures and light, and its poignant evocation of suffering. It was purchased by the Art Gallery of New South Wales in Sydney, Australia, shortly after its exhibition, giving Luminais international recognition. The work is a powerful example of historical romanticism, blending meticulous detail with a deeply emotional narrative. Its themes of rebellion, punishment, and divine intervention (through the monks) resonated with contemporary audiences.

_The Death of Chram_ (La Mort de Chramn)

Another significant work exploring Merovingian brutality is The Death of Chram. Chram (or Chramn) was a son of the Frankish King Chlothar I. He rebelled against his father, was defeated, and, along with his wife and daughters, was locked in a hut and burned alive on Chlothar's orders. Luminais depicts the horrific moment with unflinching drama, focusing on the despair and terror of the victims. Such scenes, while gruesome, were characteristic of Luminais's willingness to confront the darker aspects of early French history.

_Gallic Vedette_ (Éclaireurs gaulois)

This painting exemplifies his "painter of the Gauls" persona. It typically shows Gallic scouts on horseback, alert and watchful in a rugged landscape, embodying the vigilance and resilience of these ancient peoples. The raw energy and connection to the wild environment are palpable.

_The Last of the Merovingians_

This theme, which he may have painted in variations, touches upon the decline of the Merovingian dynasty and the rise of the Carolingians. It often evokes a sense of melancholy and the passing of an era, reflecting the "rois fainéants" (do-nothing kings) stereotype that characterized the later Merovingian rulers in popular imagination.

These works, among others, demonstrate Luminais's ability to select compelling historical or legendary narratives and translate them into powerful visual statements. He was less concerned with strict archaeological accuracy (which was still a developing field) than with capturing the spirit and drama of the events he portrayed. His approach can be contrasted with the more archaeological precision of a painter like Sir Lawrence Alma-Tadema in his depictions of Roman life, or the meticulous military detail of Ernest Meissonier.

Artistic Style and Technique

Évariste Vital Luminais was a product of the French academic system, and his style reflects its core tenets: strong draftsmanship, carefully constructed compositions, and a commitment to narrative clarity. However, his work also incorporates distinct Romantic elements, particularly in his choice of dramatic subjects, his evocative use of light and shadow (chiaroscuro), and his ability to create a palpable atmosphere.

His technique was characterized by:

Detailed Realism: Luminais paid considerable attention to rendering textures – the roughness of animal hides, the gleam of metal, the richness of fabrics. His figures, while sometimes idealized in their heroism or suffering, were anatomically sound and convincingly portrayed. This realism, however, was in service of the narrative rather than an end in itself, unlike the more objective approach of Realists like Gustave Courbet.

Dramatic Composition: He often employed dynamic compositions, using diagonals, strong contrasts, and focused lighting to heighten the emotional impact of his scenes. Figures are frequently caught in moments of intense action or profound despair.

Evocative Atmospheres: Whether depicting a misty river, a dense forest, or a burning hut, Luminais skillfully used landscape and setting to enhance the mood of his paintings. His early training with Constant Troyon, a Barbizon landscape painter, likely contributed to this sensitivity. The landscapes are rarely mere backdrops; they are integral parts of the story, often reflecting the wildness or desolation of the historical period.

Color Palette: His palette could range from somber and earthy tones, fitting for the rugged Gallic scenes or grim Merovingian tales, to richer, more vibrant colors when depicting royal trappings or moments of high drama. He understood the emotional power of color and used it effectively.

Narrative Focus: Above all, Luminais was a storyteller. Each painting was conceived to convey a specific historical or legendary episode. He aimed for legibility, ensuring the viewer could understand the narrative and empathize with the characters. This aligns with the academic tradition, which valued history painting as the highest genre precisely for its capacity to instruct and move the viewer.

While his style was broadly academic, it possessed a certain raw energy and dramatic intensity that distinguished it from the more polished and serene classicism of some of his contemporaries like Jean-Auguste-Dominique Ingres (though Ingres was of an earlier generation, his influence on academic ideals persisted) or the often more sentimental works of Bouguereau. Luminais's historical figures feel less like classical statues and more like flesh-and-blood participants in brutal, formative events. His work shares some of the dramatic fervor found in Romantic painters like Eugène Delacroix, particularly in Delacroix's historical pieces like Liberty Leading the People or The Massacre at Chios, though Luminais's execution remained more tightly controlled and less painterly than Delacroix's.

Contemporaries and Influences

Luminais operated within a vibrant and evolving artistic landscape in 19th-century Paris. His primary influences were his teachers: Léon Cogniet, who instilled in him the principles of historical painting, and Constant Troyon, who sharpened his eye for naturalistic detail and atmosphere.

Among his contemporaries in the realm of academic and historical painting were:

Jean-Léon Gérôme (1824-1904): A towering figure of French academic art, Gérôme was renowned for his meticulously detailed historical scenes, often set in classical antiquity or the Middle East (Orientalism). While both were academic historical painters, Gérôme's style was generally more polished and focused on archaeological reconstruction.

Alexandre Cabanel (1823-1889): Famous for works like The Birth of Venus, Cabanel was a master of the idealized female nude and mythological subjects, highly favored by the Salon and Emperor Napoleon III.

William-Adolphe Bouguereau (1825-1905): Another hugely successful academic painter, Bouguereau specialized in mythological, religious, and idyllic genre scenes, characterized by their smooth finish and sentimental appeal.

Ernest Meissonier (1815-1891): Known for his incredibly detailed and small-scale historical and military paintings, particularly scenes from the Napoleonic Wars. Meissonier's meticulousness was legendary.

Paul Delaroche (1797-1856): Though of an earlier generation, Delaroche's influence on historical painting was significant. He specialized in dramatic, often tragic scenes from English and French history, rendered with a smooth, detailed technique that appealed to popular taste. Luminais shared Delaroche's penchant for dramatic historical narratives.

Luminais also had students, passing on his knowledge and approach. One notable student was the American artist Emily Sartain (1841-1927), who studied with him in Paris. Sartain became an influential painter, engraver, and art educator, serving as the principal of the Philadelphia School of Design for Women for many years. Her training with Luminais would have provided her with a strong academic foundation.

The artistic environment also included movements that challenged academic dominance:

Realism: Led by Gustave Courbet (1819-1877), Realism sought to depict ordinary people and everyday life without idealization, often tackling social issues. Courbet's A Burial at Ornans was a landmark of this movement.

Impressionism: Emerging in the 1870s, artists like Claude Monet (1840-1926), Edgar Degas (1834-1917), Pierre-Auguste Renoir (1841-1919), and Camille Pissarro (1830-1903) revolutionized painting with their focus on capturing fleeting moments, the effects of light and color, and scenes of modern life, painted en plein air.

Luminais remained largely committed to the academic tradition throughout his career, even as these newer movements gained traction. His choice of historical subjects, particularly those related to French national origins, ensured continued interest from the public and official institutions.

Personal Life and Character

Details about Évariste Vital Luminais's personal life are less extensively documented than his artistic career, which is common for many artists of his era unless they were particularly flamboyant or left copious personal writings.

We know that he was married twice. His first wife was Anne Foiret. Together, they had one daughter, Marthe Luminais. After Anne Foiret's passing, Luminais married again. His second wife was Hélène Luminais (née Tréhot), who had been one of his students or apprentices. This was not an uncommon occurrence in artistic circles, where masters and pupils often formed close bonds. Hélène herself was an artist, though her work is less known than her husband's.

Luminais divided his time between his studio in Paris, where he would have engaged with the art world, exhibited at the Salon, and taken on commissions, and a country residence. He reportedly spent a significant part of his career working in his studio in the countryside, possibly in Brittany or a region that inspired his historical and rustic scenes. This would have allowed him to immerse himself in environments that perhaps felt closer to the ancient landscapes he depicted.

He was a founding member of the Société des Artistes Français, an organization established in 1881 by artists to manage the Paris Salon after the French state began to withdraw its official sponsorship. This indicates his active participation in the institutional structures of the art world of his time.

While specific anecdotes about his personality are scarce in readily available sources, his dedication to his chosen themes, his consistent output, and his success within the academic system suggest a disciplined and focused individual. His choice of often violent and dramatic subjects might imply a fascination with the more tumultuous aspects of human history and legend.

Later Years, Legacy, and Critical Reception

Évariste Vital Luminais continued to paint and exhibit throughout his life. He maintained his studio in Paris and also spent time at his country house in Douadic, in the Indre department of central France. This rural retreat likely provided inspiration and a tranquil environment for his work, away from the bustle of Paris.

His reputation as a skilled historical painter, particularly of Gallic and Merovingian subjects, was well-established. He received ongoing recognition, including the gold medal at the Exposition Universelle of 1889, a significant honor late in his career. His works were acquired by provincial museums in France and, as seen with The Sons of Clovis II, by international collections.

Luminais passed away on May 15, 1896, in Paris, at the age of 74. He was buried in the small cemetery of Douadic, the village where he had his country home, indicating his attachment to this rural part of France. In his birthplace of Nantes, a street, Rue Évariste Luminais, was named in his honor, a lasting tribute from his native city.

In terms of critical reception, Luminais was generally well-regarded during his lifetime, especially within academic circles and by a public interested in historical narratives. His dramatic storytelling and technical skill were appreciated. However, by the late 19th century, the artistic landscape was rapidly changing. The rise of Impressionism and Post-Impressionism shifted critical attention towards more avant-garde styles that broke decisively with academic conventions. In this context, some critics might have viewed Luminais's work as traditional or even old-fashioned compared to the innovations of artists like Monet, Van Gogh, or Cézanne.

For much of the 20th century, academic art of the 19th century, including Luminais's, was often overshadowed or dismissed by art historians focused on the modernist narrative. However, in more recent decades, there has been a scholarly re-evaluation of academic art. Art historians now recognize the skill, cultural significance, and distinct appeal of artists like Luminais. His work is seen as an important reflection of 19th-century historicism, nationalism, and the romantic fascination with the distant past. His paintings offer valuable insights into how earlier periods of French history were imagined and visually constructed for his contemporaries.

Today, his works are appreciated for their dramatic power, their contribution to the genre of history painting, and their specific focus on the often-overlooked early periods of French history. He remains a key figure for understanding the visual culture of 19th-century France and its engagement with national identity.

Luminais's Works in Public Collections

Évariste Vital Luminais's paintings are held in various public collections, primarily in France, but also internationally. These institutions preserve his legacy and allow contemporary audiences to engage with his unique vision of history.

Key institutions housing his works include:

Musée des Beaux-Arts de Rouen: This museum holds the renowned version of Les Énervés de Jumièges (The Enervated Sons of Jumièges), one of his most celebrated paintings. Its location in Rouen, near the actual Jumièges Abbey, adds a layer of historical resonance.

Art Gallery of New South Wales, Sydney, Australia: As mentioned, this gallery acquired The Sons of Clovis II (another title for Les Énervés de Jumièges or a very similar version/study) in 1880, shortly after its exhibition at the Paris Salon. This early international acquisition highlights the appeal of his work beyond French borders.

Musée d'Arts de Nantes: His hometown museum holds several of his works, reflecting his local importance. This is common for French regional museums, which often prioritize artists born in or associated with their area.

Musée des Beaux-Arts de Quimper: Located in Brittany, a region whose legends and history often inspired Luminais, this museum holds works such as Le Prêtre de Kerlaz (The Priest of Kerlaz, 1852), reflecting his engagement with Breton themes.

Musée des Beaux-Arts de Dunkerque (Dunkirk): This museum is noted as holding Les Barbares avant Rome (Barbarians before Rome), a title indicative of his Gallic themes.

Musée d'Orsay, Paris: While primarily known for its Impressionist and Post-Impressionist collections, the Musée d'Orsay also houses academic art from the period, and Luminais's works or studies may be found there or in related national collections.

Campbell Gallery (location specifics may vary, often private or smaller collections): Mentioned as holding Le Retour de chasse ou Braccoirs bretons (The Return from the Hunt, or Breton Poachers, 1861), a genre scene with a Breton flavor.

Musée National d'Archéologie, Saint-Germain-en-Laye: While perhaps not holding paintings, this museum, focused on French archaeology (including Gallic and Merovingian periods), has hosted exhibitions related to the historical periods Luminais depicted, and his work could be featured in such contexts for its illustrative power.

Many other provincial French museums likely hold examples of his work, as his paintings were popular and aligned with the 19th-century taste for historical subjects. His pieces also appear in private collections and occasionally come up for auction. The distribution of his art underscores his national reputation and his specific appeal to regions with strong historical connections to his chosen subjects.

Conclusion

Évariste Vital Luminais stands as a significant, if sometimes overlooked, figure in 19th-century French art. As the "painter of the Gauls" and a vivid chronicler of the Merovingian age, he brought to life a distant and often brutal past with dramatic flair and academic skill. His paintings resonated with a contemporary desire for national historical narratives, offering compelling visual interpretations of France's origins. While the tides of artistic taste shifted towards modernism, Luminais's work endures as a testament to the power of historical imagination in art. His ability to weave together meticulous detail, evocative atmospheres, and powerful human drama ensures his place as a distinctive voice within the rich tapestry of French academic painting, offering a window into a world both ancient and vividly re-imagined. His legacy is not just in the canvases themselves, but in the enduring fascination with the historical epochs he so passionately depicted.