Herbert Gustave Schmalz, later known as Herbert Gustave Schmalz-Carmichael, stands as a notable figure in the landscape of late Victorian art. Born in England in 1856 and passing away in 1935, his career spanned a period of significant artistic transition. He is often associated with the later echoes of the Pre-Raphaelite movement, blending its detailed realism and romantic sentiment with a penchant for historical, biblical, and Orientalist themes. His work, characterized by meticulous execution and dramatic compositions, captured the imagination of his contemporaries and continues to offer a fascinating window into the artistic tastes of his era.

Early Life and Artistic Foundations

Herbert Gustave Schmalz was born into a family with artistic and international connections. His father, Gustav Schmalz, was a German consul, and his mother was the daughter of the respected British marine painter, James Wilson Carmichael. This familial link to the art world likely provided an early exposure and encouragement for young Herbert's burgeoning talents. His original name, John Wilson Carmichael, paid homage to his maternal grandfather, a significant artist in his own right, known for his evocative seascapes and depictions of naval events.

Schmalz pursued a formal art education, a prerequisite for any aspiring painter aiming for recognition in the highly structured Victorian art world. He initially studied at the South Kensington Art School, a key institution for art and design education in London. Following this, he further honed his skills at the prestigious Royal Academy Schools. Here, he would have been immersed in a curriculum that emphasized rigorous academic drawing, the study of anatomy, and the emulation of Old Masters, all considered essential for a painter of historical and narrative subjects. During his formative years, he reportedly came under the influence of established artists such as Frank Dicksee, known for his chivalric and sentimental paintings, and possibly Stephen Steele, though Dicksee's impact is more clearly discernible in Schmalz's romantic leanings.

The Pre-Raphaelite Influence and Romantic Sensibilities

While Schmalz was not a member of the original Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood, which had been founded in 1848 by figures like Dante Gabriel Rossetti, John Everett Millais, and William Holman Hunt, his work clearly demonstrates an affinity with the movement's later manifestations. The Pre-Raphaelite emphasis on truth to nature, meticulous detail, vibrant colour, and subjects drawn from literature, religion, and history resonated deeply within the Victorian art scene for decades. Schmalz adopted many of these tenets, particularly the careful rendering of textures, the emotional intensity of his figures, and the narrative clarity of his compositions.

His style can be described as a fusion of academic precision with the romantic and often sentimental spirit characteristic of much late Victorian painting. He was a contemporary of artists like John William Waterhouse, whose mythological and Arthurian scenes share a similar romantic intensity, and Lawrence Alma-Tadema, whose meticulously researched depictions of classical antiquity set a high bar for historical accuracy and opulent detail. Schmalz, like these artists, sought to transport viewers to other times and places, imbuing his scenes with a palpable sense of drama and emotion.

Historical and Biblical Narratives

A significant portion of Schmalz's oeuvre is dedicated to historical and biblical subjects. These themes were immensely popular in the 19th century, offering artists grand stages for dramatic storytelling, moral instruction, and the display of technical skill. Schmalz excelled in this arena, creating works that were both visually compelling and emotionally engaging.

One of his most acclaimed early works was Too Late, exhibited at the Royal Academy in 1884. While the specific subject is not always immediately clear without context, such titles often hinted at poignant narratives of missed opportunities or tragic outcomes, appealing to the Victorian fondness for sentimental storytelling.

A pivotal moment in his career, particularly for his biblical paintings, was his journey to Jerusalem and the Holy Land in 1890. This voyage provided him with firsthand experience of the landscapes, light, and cultures of the Near East, lending an air of authenticity to his subsequent religious works. This practice of artists travelling to the Holy Land for research was common; William Holman Hunt, for instance, had made extensive travels to the region to inform his own highly detailed biblical paintings, such as The Scapegoat and The Light of the World. Schmalz's trip undoubtedly enriched his visual vocabulary and deepened his understanding of the settings for his New Testament scenes.

Among his notable biblical works is The Great Awakening (circa 1890), a piece that likely reflects the spiritual and emotional intensity he sought to convey, characteristic of Victorian religious art which often focused on moments of profound personal revelation or divine intervention.

Masterpiece: Zenobia's Last Look on Palmyra

Perhaps one of Schmalz's most famous historical paintings is Zenobia's Last Look on Palmyra, completed in 1888. This monumental work depicts the 3rd-century Queen Zenobia of the Palmyrene Empire, a powerful and defiant ruler who challenged Roman authority. The painting captures a moment of profound pathos: Zenobia, defeated and about to be taken to Rome as a captive, gazes back at her beloved city, Palmyra, which is being sacked by Roman soldiers.

The composition is dramatic, with Zenobia positioned centrally, her regal bearing contrasting with her evident despair. Schmalz's meticulous attention to historical detail in costume and architecture, combined with the rich colours and emotive portrayal of the queen, made this painting a significant achievement. It resonated with Victorian audiences, who were fascinated by tales of heroic figures from antiquity, particularly strong female characters. The work compares favorably with other grand historical statements of the era, such as those by Sir Edward Poynter or Frederic Leighton, who also depicted powerful women from history and mythology.

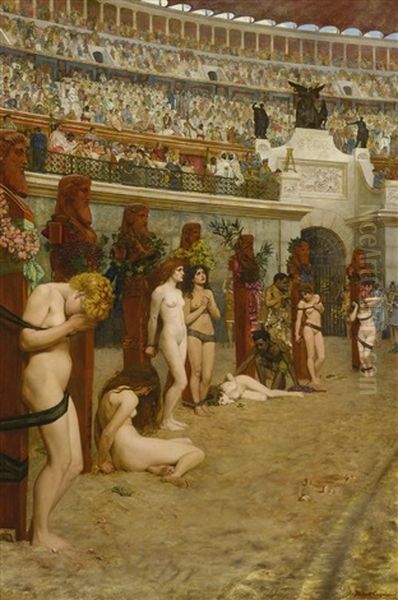

Masterpiece: Faithful unto Death ('Christianes ad Leones!')

Another of Schmalz's most enduring images is Faithful unto Death ('Christianes ad Leones!'), painted around 1887 or 1888. The title, with its Latin exclamation "Christians to the Lions!", immediately evokes the persecution of early Christians in the Roman Empire. The painting depicts a young Christian woman in an arena, calmly awaiting martyrdom as lions are presumably about to be released. Her serene expression and upward gaze suggest unwavering faith in the face of imminent death.

This work is a powerful example of Victorian religious sentimentality and the era's fascination with themes of martyrdom and steadfast faith. The painting's emotional impact is heightened by the contrast between the vulnerable figure of the woman and the implied brutality of her fate. It is a subject that would have been familiar to Victorian audiences through literature and other artworks, such as Jean-Léon Gérôme's The Christian Martyrs' Last Prayer. Schmalz’s rendition is particularly poignant and became widely popular, reproduced in engravings and prints. The original painting is now housed in the Calouste Gulbenkian Museum in Lisbon, Portugal, a testament to its artistic merit.

The Allure of Orientalism

Like many of his contemporaries, Schmalz was drawn to Orientalist themes – subjects inspired by the cultures of North Africa, the Middle East, and Asia. His journey to Jerusalem in 1890 was instrumental in developing this aspect of his work. Orientalism in art provided an escape from the industrialised West, offering exotic locales, vibrant colours, and intriguing customs. Artists such as John Frederick Lewis, who lived for many years in Cairo, and the aforementioned Gérôme, were leading proponents of this genre.

Schmalz’s Orientalist paintings often combined biblical narratives with his observations of the Near East, creating a sense of authenticity and immediacy. These works appealed to the Victorian public's curiosity about distant lands and their desire for art that was both visually rich and narratively engaging. His ability to render textures, from sumptuous fabrics to ancient stonework, was particularly suited to these exotic subjects.

Literary Inspirations and "A Dream of Fair Women"

Schmalz also drew inspiration from literature, particularly the works of William Shakespeare. His painting Imogen, for example, depicts a character from Shakespeare's play Cymbeline. Such literary subjects were a staple of Victorian art, allowing painters to explore complex human emotions and dramatic situations familiar to their audience. Artists like Edwin Austin Abbey and members of the Pre-Raphaelite circle, including Millais with his Ophelia, frequently turned to Shakespearean themes.

In 1900, Schmalz held a significant solo exhibition titled "A Dream of Fair Women." This exhibition, likely inspired by Alfred, Lord Tennyson's poem of the same name, would have showcased a series of paintings celebrating female beauty in various historical, mythological, and allegorical guises. Such an exhibition underscored his reputation as a painter of elegant and idealized femininity, a theme popular with artists like George Frederic Watts and Albert Moore, who often depicted statuesque and graceful female figures. The exhibition would have been a major event, consolidating his position in the London art world.

A Shift Towards Portraiture

Later in his career, particularly after 1895, Schmalz increasingly turned his attention to portraiture. This was a common trajectory for successful narrative painters in the Victorian and Edwardian eras. Portraiture offered consistent commissions and was highly valued by the affluent middle and upper classes. While perhaps less creatively ambitious than his grand historical canvases, his portraits would have benefited from his skilled draughtsmanship and his ability to capture a sitter's likeness and character.

This shift mirrored the careers of other prominent artists like Luke Fildes and Hubert von Herkomer, who, despite early successes in social realist or historical genres, became highly sought-after portrait painters. Schmalz's experience in depicting expressive figures in his narrative works would have served him well in the more intimate genre of portraiture.

Personal Life: The Change of Name

A significant event in Schmalz's personal life was his decision to change his surname. In 1918, following the defeat of Germany in World War I, anti-German sentiment was widespread in Britain. Given his German paternal heritage and surname, Schmalz opted to change his name to Herbert Gustave Carmichael. This was a poignant decision, as it involved adopting his mother's maiden name and, by extension, honouring his maternal grandfather, the painter James Wilson Carmichael. This change reflected the societal pressures of the time and a desire to affirm his British identity. He is thus sometimes referred to as Herbert Schmalz-Carmichael.

Friendships and Artistic Circle

Throughout his career, Schmalz cultivated friendships with prominent figures in the art world. He was known to be on good terms with William Holman Hunt, one of the founding members of the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood. This connection underscores Schmalz's alignment with Pre-Raphaelite ideals, even as a later practitioner. He also enjoyed a friendship with Frederic Leighton, President of the Royal Academy and a leading figure of the classical Olympian movement. Leighton's own work, though stylistically different, shared Schmalz's commitment to high finish and grand themes. Another associate was Val Prinsep, a contemporary known for his historical scenes and association with the Pre-Raphaelites and Leighton's circle. These connections place Schmalz firmly within the mainstream of the established London art scene.

Later Years and Legacy

Herbert Gustave Schmalz-Carmichael continued to paint into the early 20th century, though the artistic landscape was rapidly changing with the advent of Modernism. The grand narrative paintings and romantic idealism that had defined much of his career were becoming less fashionable as new movements like Post-Impressionism and Cubism gained traction. He passed away in London in 1935 at the age of 79.

Today, Schmalz's work is appreciated for its technical skill, its embodiment of late Victorian aesthetics, and its contribution to the genres of historical, biblical, and Orientalist painting. While perhaps not as revolutionary as some of his avant-garde contemporaries, he was a highly accomplished artist who produced works of considerable beauty and emotional power. His paintings offer a valuable insight into the tastes and preoccupations of his time, reflecting a world that valued narrative clarity, moral sentiment, and the allure of the historical and exotic. His most famous works, such as Zenobia's Last Look on Palmyra and Faithful unto Death, remain compelling examples of late 19th-century academic and romantic art, securing his place in the annals of British art history. His paintings can be found in various public and private collections, allowing contemporary audiences to engage with the rich visual culture of the Victorian era.