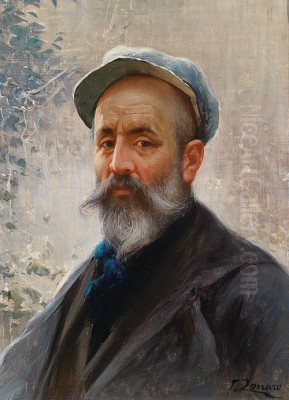

Fausto Zonaro stands as a significant figure in late 19th and early 20th-century art, a bridge between Italian Realism and the captivating allure of the East. An Italian national, born in 1854 in Masi, within the province of Padua, Zonaro carved a unique path for himself, culminating in his prestigious role as the last official Court Painter to the Ottoman Sultan. His life (1854-1929) spanned a period of immense change, both in Europe and in the Ottoman Empire, and his canvases provide invaluable visual records of a world on the cusp of transformation. He is celebrated primarily for his vivid depictions of Ottoman life, history, and the vibrant atmosphere of Constantinople (modern-day Istanbul).

Early Life and Artistic Formation

Fausto Zonaro's journey into the world of art began not with privilege, but with practical necessity. Born into a family of modest means, his initial training was far removed from the hallowed halls of art academies; he started as a carpenter's apprentice. However, his innate talent for drawing and observation could not be suppressed. Recognizing his potential, he pursued formal artistic education, marking the true beginning of his lifelong dedication to painting.

His foundational studies commenced at the Technical Institute in Lendinara. Seeking more advanced training, he later enrolled at the esteemed Cignaroli Academy in Verona. It was here, under the tutelage of the painter Napoleone Nani, that Zonaro honed his skills, particularly embracing the principles of Realism. Nani's influence likely instilled in him a commitment to accurate observation and detailed representation, traits that would become hallmarks of his later work.

Driven by ambition and a desire to broaden his artistic horizons, Zonaro did not confine his studies to Verona. He immersed himself in the vibrant art scenes of major Italian cultural centers, spending time learning and absorbing influences in Venice, Rome, and Florence. This period exposed him to various artistic currents, including the lingering traditions of academic painting and the burgeoning movements that challenged them, such as the Macchiaioli group, whose members like Giovanni Fattori and Telemaco Signorini championed realism and painting en plein air. While Zonaro developed his own distinct style, this exposure undoubtedly enriched his artistic vocabulary. His early works from this period, such as The Redemption (1888) and Nana's Departure (1888), reflect his engagement with Italian classical themes and contemporary urban life, executed with a growing technical confidence.

The Journey to Constantinople

The pivotal moment in Zonaro's career arrived in 1891 when he, along with his wife Elisa Pante (who was also a photographer and sometimes assisted him), made the bold decision to move to Constantinople, the sprawling, multicultural capital of the Ottoman Empire. This move was driven by a fascination with the East, a common sentiment among European artists of the era, but also likely by the prospect of new opportunities and patronage in a city that captivated the Western imagination.

Arriving in the bustling Pera district, the cosmopolitan heart of the city inhabited by Europeans and Levantines, Zonaro set about establishing himself. The initial years likely involved navigating a new cultural landscape, learning the rhythms of the city, and seeking commissions. Constantinople offered a staggering array of visual stimuli: ancient Byzantine churches standing alongside grand Ottoman mosques, bustling bazaars teeming with merchants from across the empire, serene views across the Bosphorus, and the intricate tapestry of daily life played out in its streets and squares.

Zonaro immersed himself in this environment, sketching and painting the city's diverse inhabitants and iconic landmarks. He began to attract attention within the local European community and among the Ottoman elite. His realistic style, combined with a sensitivity to the unique light and atmosphere of the city, distinguished his work. This period laid the groundwork for his future success, allowing him to build a reputation and forge connections that would prove crucial.

Court Painter to the Sultan

Fausto Zonaro's talent and growing reputation did not go unnoticed at the highest levels of the Ottoman state. A significant breakthrough occurred thanks to the intervention of the Russian Ambassador, Aleksandr Nelidov. Impressed by Zonaro's work, Nelidov recommended him to the Ottoman palace. This led to Zonaro gaining favour with Sultan Abdülhamid II, a ruler known for his interest in photography and, to some extent, Western artistic representation, albeit within careful constraints.

In 1896, Zonaro received the ultimate accolade: he was officially appointed Ressam-ı Hazret-i Şehriyari, or Court Painter to His Majesty the Sultan. This prestigious title made him the last artist to hold this position in the history of the Ottoman Empire. The appointment brought not only honour but also stability, a regular salary, and access to the inner circles of the Ottoman court. The Sultan bestowed upon him the Order of the Medjidie (Fourth Class), a further sign of imperial favour.

As Court Painter, Zonaro was tasked with various commissions. These included creating portraits of dignitaries, documenting important state events, and, significantly, producing historical paintings that glorified the Ottoman past. One such commission was a series depicting scenes from the life of Sultan Mehmed II, the conqueror of Constantinople. Another notable work commissioned by the Sultan depicted the Attack of Göksu. These paintings required meticulous research and a grand scale, showcasing Zonaro's versatility. His position allowed him unparalleled access to observe court ceremonies and the daily life within the palace grounds, enriching his portfolio of subjects.

Capturing the Ottoman World

While fulfilling his official duties, Zonaro continued to paint the subjects that had initially drawn him to Constantinople: the city itself and its people. His artistic style during his Istanbul years represents a fascinating fusion of his Italian Realist training and the thematic concerns of Orientalism. Unlike some Orientalist painters who relied on fantasy or second-hand accounts, Zonaro painted from direct observation, lending his work a sense of immediacy and authenticity.

He possessed a keen eye for detail and a remarkable ability to capture the effects of light, whether it was the sharp Mediterranean sun casting dramatic shadows in a narrow street, the hazy glow over the Golden Horn at sunset, or the diffused light within the covered bazaars. His canvases teem with life, depicting dervishes performing their rituals, women carrying water jars, fishermen mending nets along the Bosphorus, vendors selling their wares, and the colourful chaos of public festivals.

His subjects ranged from grand public spectacles to intimate moments of daily life. He painted iconic landmarks like the Hagia Sophia and the Blue Mosque, but also quieter corners of the city. His depictions of the Bosphorus, with its caiques and steam ferries, are particularly evocative. One of his most famous works, The Ertuğrul Cavalry Regiment Crossing the Galata Bridge (painted around 1901, based on an 1897 event), is a masterpiece of composition and movement, capturing the pageantry and military might of the Ottoman state against the backdrop of the bustling city. Another well-known piece, Fishing Boats on the Bosphorus (1910), showcases his skill in rendering water and atmosphere.

Compared to the highly finished, often dramatic or sensualized works of French Orientalists like Jean-Léon Gérôme or the Romantic visions of Eugène Delacroix, Zonaro's style often feels more grounded and documentary, though still imbued with the picturesque quality sought by Western audiences. He shared the Orientalist fascination with the "exotic," but his long residency provided a deeper, more nuanced perspective than that of a fleeting visitor. His work can be seen alongside that of other European artists active in the East, such as his fellow Italians Alberto Pasini and Amedeo Preziosi, who also specialized in Ottoman subjects, each bringing their own stylistic interpretation.

Life and Influence in Istanbul

Fausto Zonaro spent nearly two decades in Constantinople, from 1891 until 1909/1910. During this time, he became a prominent figure in the city's vibrant artistic and expatriate community, centered in the Pera district. He maintained a studio, which likely became a hub for artists and intellectuals. His wife, Elisa Pante, contributed to their artistic endeavours, particularly through her photography, which may have served as a reference for some of Fausto's compositions.

His role as Court Painter naturally brought him into contact with the Ottoman elite and the diplomatic corps. He received commissions not just from the Sultan, but also from wealthy Pashas, Ottoman officials, and foreign ambassadors. For instance, he painted a portrait of the daughter of the British Ambassador, Sir Philip W. Currie, and documented Currie's wedding festivities, indicating his integration into the highest social circles. He also interacted with cultured members of the Ottoman dynasty, such as Prince Abdülmecid Efendi, who was himself an accomplished painter and later the last Caliph.

Beyond his own painting, Zonaro played a role in the artistic life of the city. He exhibited regularly, including significant showings at the Istanbul Salons held in the early 1900s (sources mention 1901, 1902, 1903) where he presented numerous works. He also participated in international exhibitions, such as one in Munich in 1905. Furthermore, he engaged in teaching, sharing his knowledge of Western painting techniques with local students. While established figures like Osman Hamdi Bey were already prominent, Zonaro's presence and teaching likely influenced a younger generation of Turkish artists seeking to engage with European styles, contributing to the ongoing Westernization of Ottoman art, a trend also seen in the work of painters like Şeker Ahmed Paşa.

The Winds of Change: Revolution and Departure

The relative stability of Sultan Abdülhamid II's reign, during which Zonaro flourished, came to an end with the Young Turk Revolution in 1908. This dramatic political upheaval aimed to restore the Ottoman constitution and limit the Sultan's absolute power. Zonaro, perhaps sensing the shift in power or genuinely sympathetic to the cause, aligned himself with the new movement.

He captured this historical moment in paint, creating works that celebrated the revolution. His painting Liberty (1908) allegorically depicted the newfound freedom, while his portrait of Enver Pasha, one of the leading figures of the revolution, further signaled his support for the Committee of Union and Progress (CUP), the political organization behind the uprising.

However, this alignment with the new regime did not secure his position. Following the deposition of Sultan Abdülhamid II in 1909, Zonaro entered into disputes with the new government, reportedly over his salary and the terms of his position as Court Painter. The exact nature of the disagreement remains somewhat unclear, but the outcome was definitive: his title was revoked, and his official connection to the Ottoman state was severed. This abrupt change, coupled with the political uncertainties, prompted Zonaro to leave the city that had been his home and primary source of inspiration for nearly twenty years. He departed Istanbul around 1910.

Return to Italy and Later Years

Leaving Constantinople marked the end of a major chapter in Fausto Zonaro's life and career. He returned to his native Italy, eventually settling in the coastal town of Sanremo on the Italian Riviera. While the vibrant, exotic subjects of the Ottoman capital were no longer part of his daily experience, he continued to paint prolifically.

His later work included landscapes of the Italian Riviera, portraits, and likely, paintings based on the numerous sketches and memories accumulated during his years in the East. The influence of his time in Constantinople remained palpable, even if the immediate subject matter shifted. He may have revisited Oriental themes from memory or continued to find buyers interested in his unique specialization. He had absorbed influences from various movements throughout his career, including potentially the bravura brushwork associated with artists like Giovanni Boldini, whom he might have encountered or whose work he saw during visits to Paris, and perhaps even the lighter palette of Impressionism, though his core style remained rooted in Realism.

He continued to exhibit his work in Italy. Despite leaving the center stage of the Ottoman court, he remained a respected artist. He passed away in Sanremo in 1929, leaving behind a rich and diverse body of work that documented his personal artistic journey and a unique historical epoch. His legacy was kept alive through family efforts and growing scholarly interest.

Artistic Legacy and Historical Evaluation

Fausto Zonaro's primary artistic achievement lies in his extensive and insightful portrayal of the Ottoman Empire, particularly Constantinople, during the final decades of its existence. As the last Court Painter, he occupied a unique position, granting him access and perspective that few other Western artists possessed. His work serves as an invaluable historical document, capturing the architecture, ceremonies, diverse peoples, and daily rhythms of the imperial capital with a Realist's eye for detail.

He is considered a major figure within the Italian Orientalist movement, alongside contemporaries like Alberto Pasini, Pompeo Mariani, and Amedeo Preziosi, as well as other European Orientalists like Ludwig Deutsch and Rudolf Ernst. While Orientalism itself is now subject to critical re-evaluation regarding its colonial perspectives, Zonaro's long immersion in Ottoman culture arguably lends his work a degree of nuance often missing in the work of artists who only visited briefly. His paintings generally avoid the more egregious stereotypes, focusing instead on observed reality, albeit filtered through a European sensibility.

His influence extended to Turkish art as well. By introducing and teaching Western techniques and exhibiting his work prominently in Istanbul, he contributed to the development of modern Turkish painting. He provided a model for local artists grappling with representation, perspective, and oil painting techniques. His works are held in important collections in Turkey, including museums in Istanbul, as well as in private collections internationally.

Interest in Zonaro's work has continued, evidenced by exhibitions and publications. His memoirs, offering personal insights into his experiences at the Sultan's court, were published in Turkish in 2008. Scholarly books and articles, such as those by Erol Makzume and Osman G. Öztürk (2010) and Taha Toros, continue to explore his life and art. Exhibitions, including a notable one in 1979 featuring works from Italian private collections and more recent shows like the 2024 exhibition "From Venice to Istanbul," ensure his art reaches new audiences. While minor controversies exist, such as occasional debates about the authenticity of certain works attributed to him (like Margarethe Fehim), his overall importance is undisputed. He remains a key figure for understanding late Ottoman culture and the complex artistic exchanges between East and West.

Conclusion

Fausto Zonaro's life was a remarkable journey from a carpenter's apprentice in provincial Italy to the esteemed Court Painter of the Ottoman Sultan. His legacy is twofold: he was a skilled painter within the Italian Realist tradition, adept at capturing light, detail, and human character; and he was a crucial visual chronicler of the late Ottoman Empire. His canvases offer a window onto the vanished world of Constantinople in the final years of the Sultanate, rendered with an intimacy born of long residence and careful observation. Bridging Italian artistry and Ottoman subject matter, Zonaro created a unique body of work that continues to fascinate historians and art lovers alike, securing his place as a distinctive master straddling two cultures.