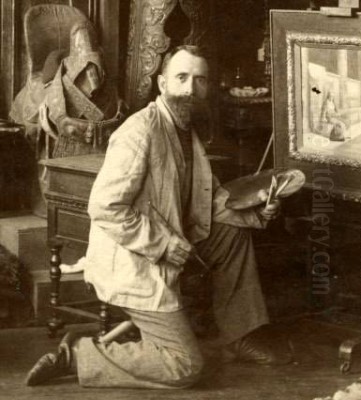

Theodore Jacques Ralli stands as a significant figure in the landscape of 19th-century European art, particularly within the captivating and often complex genre of Orientalism. A painter of Greek descent, born in the cosmopolitan heart of the Ottoman Empire, Ralli navigated the cultural currents between East and West, forging a successful career centered primarily in Paris, the era's artistic epicenter. His work is celebrated for its meticulous detail, sensitive handling of light and color, and evocative depictions of life in North Africa and the Near East, blended occasionally with reflections of his own Hellenic heritage. Ralli's journey from Constantinople to the esteemed Paris Salon offers a fascinating glimpse into the life of an artist shaped by diverse cultural influences and the prevailing artistic tastes of his time.

Early Life and Formative Influences

Born on February 16, 1852, in Constantinople (modern-day Istanbul), Théodore Jacques Ralli, also known as Theodoros Rallis (Θεόδωρος Ράλλης), entered a world brimming with cultural intersections. His family, originally hailing from the Greek island of Chios, belonged to the prosperous Greek diaspora community within the Ottoman capital. This background provided Ralli with an innate familiarity with the Eastern Mediterranean world that would later permeate his art. His father was a successful merchant with business interests extending as far as London, ensuring the young Ralli received a privileged upbringing and education.

Recognizing his artistic inclinations, Ralli's path led him away from the family business towards the pursuit of painting. A pivotal moment came with the support of King Otto of Greece, which facilitated his move to Paris. This relocation was crucial, placing him at the very center of the European art world during a period of immense artistic ferment. Paris offered unparalleled opportunities for training and exposure, setting the stage for his development as a professional artist.

Parisian Training: The École des Beaux-Arts and Academic Masters

In Paris, Ralli enrolled at the prestigious École des Beaux-Arts, the bastion of French academic art training. This institution emphasized rigorous instruction in drawing, anatomy, perspective, and the study of classical and Renaissance masters. The goal was to produce artists skilled in representational accuracy, compositional harmony, and the grand manner suitable for historical, mythological, or allegorical subjects. Within this demanding environment, Ralli sought out instruction from leading figures of the Academic tradition, notably Jean-Léon Gérôme and Jean-Jules-Antoine Lecomte du Nouy.

Jean-Léon Gérôme (1824-1904) was not only a highly respected academic painter and sculptor but also one of the most prominent and influential Orientalist artists of his generation. His studio attracted students from across Europe and America. Gérôme was renowned for his polished technique, archaeological precision (sometimes debated), and dramatic, often highly detailed scenes set in the Middle East, North Africa, and the classical world. Studying under Gérôme undoubtedly provided Ralli with a strong foundation in academic draftsmanship and finish, as well as direct exposure to the themes and aesthetics of Orientalism.

Jean-Jules-Antoine Lecomte du Nouy (1842-1923), another significant academic painter and himself a student of Gérôme, also played a role in Ralli's education. Lecomte du Nouy was similarly drawn to historical and Orientalist subjects, known for works like The Bearers of Evil News (1871) and depictions of Egyptian life. Training under these masters immersed Ralli in the technical skills and thematic preoccupations that would define much of his career. He learned the importance of careful composition, anatomical accuracy, the rendering of textures, and the creation of a smooth, highly finished surface, all hallmarks of the academic style.

Embracing Orientalism: Travels and Inspiration

While grounded in the academic tradition, Ralli's artistic identity became inextricably linked with Orientalism. This broad artistic movement, peaking in the 19th century, reflected Europe's burgeoning fascination with the cultures, landscapes, and peoples of North Africa, the Middle East (the "Orient"), and Asia. Fueled by colonialism, increased travel, archaeological discoveries, and romantic literature, Orientalist art ranged from ethnographic documentation to highly imaginative, often sensual or dramatic, portrayals of exotic life. Artists like Eugène Delacroix (1798-1863) had pioneered the genre earlier in the century with his vibrant depictions of North Africa, followed by generations who explored its varied facets.

Ralli fully embraced this trend, but with the advantage of his own background and extensive personal experience. He undertook numerous journeys throughout the Ottoman Empire, Greece, Egypt, and Palestine. These travels were not mere tourist excursions; they were vital sources of inspiration and subject matter. He sketched, collected artifacts, and absorbed the atmospheres of the places he visited. Unlike some Orientalist painters who relied heavily on studio props and imagination, Ralli's direct observations lent a degree of authenticity and intimacy to his depictions of daily life, interiors, and local customs.

His connection to Egypt became particularly strong. He established a second studio in Cairo, allowing him to spend considerable time there, immersing himself in the local environment. This prolonged engagement distinguishes him from artists who made only brief tours. Living and working in Cairo enabled Ralli to move beyond superficial exoticism and capture nuances of light, architecture, and social interaction with greater familiarity.

Artistic Style: Detail, Light, and Atmosphere

Ralli's mature style synthesized his academic training with his Orientalist interests. His paintings are characterized by a high degree of realism and meticulous attention to detail. He rendered fabrics, architectural elements, furnishings, and human features with remarkable precision. This technical polish, inherited from Gérôme and the academic school, appealed to the tastes of Salon juries and bourgeois collectors who valued craftsmanship and verisimilitude.

However, Ralli often tempered the sometimes harsh clarity of academic realism with a softer, more atmospheric handling of light and color. His palette, while capable of richness, often favored subtle harmonies and nuanced tones. He demonstrated a particular sensitivity to the effects of light, whether depicting the cool, diffused illumination within a mosque or church, the dappled sunlight in a courtyard, or the warm glow of lamps in an interior scene. This skillful manipulation of light contributed significantly to the mood and emotional resonance of his works, often creating a sense of tranquility, intimacy, or quiet contemplation.

While clearly influenced by Gérôme, Ralli's work often possesses a gentler, less overtly dramatic quality. He frequently focused on intimate genre scenes – moments of prayer, quiet domesticity, women relaxing in interiors, scholars reading, or artisans at work. While Gérôme might tackle grand historical reconstructions or scenes with underlying tension (like The Snake Charmer), Ralli often preferred capturing the rhythm of everyday life. His figures, though precisely drawn, can sometimes feel more observed than staged, conveying a sense of quiet dignity.

Key Themes and Subjects

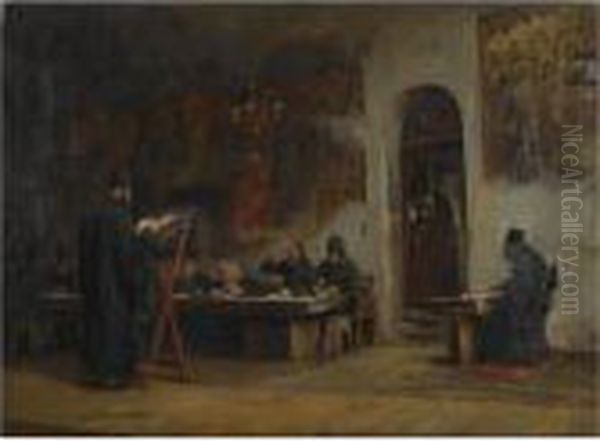

Ralli's oeuvre explored a range of subjects, primarily centered on his Orientalist and Greek interests. Scenes of daily life in Egypt and the broader Middle East were recurrent. He depicted bustling marketplaces, quiet street corners, the interiors of homes and workshops, and moments of leisure and social interaction. Architectural studies also featured prominently, showcasing his ability to render the intricate details of mosques, Cairene houses, and monastic buildings.

Religious life was another significant theme. Reflecting both the Islamic context of many of his travels and his own Greek Orthodox background, Ralli painted scenes set within mosques, churches, and monasteries. Works depicting prayer, religious instruction, or monastic routines allowed him to explore different facets of faith and community within the Eastern Mediterranean. These paintings often emphasize the serene atmosphere of sacred spaces and the devotion of the figures within them.

The female figure, particularly within interior settings, was a common subject, aligning with popular Orientalist tropes. Ralli painted numerous scenes of women in harems or domestic interiors, often depicted reclining, playing music, or engaged in quiet activities. While sometimes featuring semi-nude figures, his approach was generally considered more restrained and less overtly eroticized than that of some contemporaries. These works catered to the European fascination with the perceived mystery and sensuality of the harem, a recurring motif in Orientalist art explored by artists from Ingres (La Grande Odalisque, 1814) to Gérôme himself.

Ralli also occasionally incorporated elements of Japonisme, the late 19th-century European craze for Japanese art and aesthetics. While primarily an Orientalist focused on the Near East, the title Japonaiserie associated with him suggests an engagement with this trend, perhaps through the inclusion of Japanese objects within his compositions or stylistic experiments, reflecting the era's global artistic cross-currents.

Representative Works

Several paintings stand out as representative of Ralli's style and thematic concerns:

Sleeping Concubine: This work exemplifies the intimate interior scenes featuring female figures that were popular with Ralli's audience. Likely depicting a woman in a harem setting, it showcases his skill in rendering textures (fabrics, carpets) and his characteristic use of soft, atmospheric light. The subject aligns with common Orientalist themes of sensuality and repose within an exoticized domestic space.

Promenade at dusk in Maroc: Capturing an outdoor scene, this painting likely demonstrates Ralli's ability to evoke a specific time and place through light and atmosphere. Depicting figures in a Moroccan setting during the evocative twilight hours, it would highlight his interest in genre scenes and the picturesque qualities of North African life.

Praying in a Greek Church, Mount Athos or Refectory in a Greek Monastery: These titles point to Ralli's engagement with his own Greek Orthodox heritage. Such works allowed him to apply his detailed, atmospheric style to subjects distinct from the Islamic world often central to Orientalism. They depict moments of collective worship or monastic life, rendered with the same attention to architectural detail and human presence found in his Middle Eastern scenes, offering a unique blend of cultural perspectives.

Woman in an Interior, Cairo: This likely represents another facet of his Egyptian work, focusing perhaps on a more straightforward depiction of domestic life. It would showcase his ability to capture the specific details of Cairene architecture and furnishings, providing a glimpse into the everyday world he observed during his time there.

These examples illustrate the core elements of Ralli's art: technical precision learned in Paris, a focus on Orientalist and Greek subjects drawn from personal experience, and a distinctive handling of light and atmosphere that imbued his scenes with a sense of quiet intimacy or reverence.

Interactions and Collaborations: The Cairo Art Scene

Ralli's time in Egypt was not spent in isolation. He actively engaged with the local and expatriate artistic community. A notable interaction involved Abbate Pasha, a significant figure in Cairo's cultural life and the founder of the Cercle Artistique, an art society connected with artists and writers in Paris. According to records, it was at Ralli's initiative that Abbate Pasha and the Cercle Artistique organized a major art exhibition at the Cairo Opera House.

This event was unprecedented in Cairo at the time and showcased works by European Orientalist artists who were passing through or residing in the city, including students of Ralli's former teacher, Jean-Léon Gérôme. The exhibition attracted considerable attention, attended by members of the Egyptian royal family, British officials, and Cairo's high society. This collaboration highlights Ralli's role not just as a painter of Egyptian scenes but as an active participant in fostering artistic exchange within Cairo itself. His established reputation and connections likely played a key part in making such an event possible.

Career Success and Recognition

Theodore Jacques Ralli achieved considerable success and recognition during his lifetime. He began exhibiting at the prestigious Paris Salon in 1875 and became a regular participant, showcasing his meticulously crafted paintings to a wide audience. The Salon was the primary venue for artists seeking official recognition and patronage in France, and consistent acceptance was a mark of professional achievement.

His work was well-received by critics and collectors alike. The combination of exotic subject matter, rendered with reassuring academic skill, appealed to prevailing tastes. His paintings found buyers across Europe and likely in America as well. His success was formally acknowledged through various honors. He was appointed a member of the jury for painting at the Exposition Universelle (World's Fair) in Paris in 1900, a position of significant prestige indicating his respected standing within the French art establishment. In 1901, his contributions were further recognized when he was awarded the Cross of the Legion of Honour, one of France's highest civilian decorations.

This level of success places Ralli among the prominent Orientalist painters of his generation, alongside artists like Ludwig Deutsch (1855-1935) and Rudolf Ernst (1854-1932), who also specialized in highly detailed depictions of Middle Eastern life, often sharing similar themes and a polished technique derived from the academic tradition, particularly Gérôme's influence. Frederick Arthur Bridgman (1847-1928), an American pupil of Gérôme, also achieved great fame with his North African scenes. Ralli operated within this successful milieu, carving out his own niche characterized by his Greek background and often gentler atmospheric effects.

Orientalist Tropes and Critical Perspectives

Like much Orientalist art, Ralli's work is subject to modern critical perspectives that examine its relationship with colonialism and cultural representation. The Orientalist genre often perpetuated stereotypes and presented a romanticized, sometimes patronizing, view of non-European cultures. Themes like the languid harem, the bustling bazaar, or the fervent prayer could reinforce Western notions of the "Orient" as timeless, sensual, irrational, or fundamentally different from the "progressive" West.

Ralli's depictions of female nudes or semi-nudes within harem settings, while perhaps more restrained than some, still participate in this tradition of exoticizing and objectifying Eastern women for a Western male gaze. While his long stays in Egypt may have lent authenticity to his details, the choice of subjects often aligned with established, commercially successful Orientalist formulas. Critics might argue that his focus on picturesque daily life sometimes overlooked the complex social and political realities of the regions he depicted, particularly during a period of increasing European colonial influence.

However, it's also important to view Ralli within his historical context. He was working within a popular and accepted genre, utilizing the artistic language and responding to the market demands of his time. His Greek heritage perhaps offered him a slightly different perspective than some of his purely Western European contemporaries, potentially fostering a deeper empathy or understanding, though this is difficult to definitively ascertain from the paintings alone. His works depicting Greek Orthodox life, set within the East, further complicate a simple reading of him as solely an outsider depicting an exotic "other."

Ralli's Greek Identity in His Art

While internationally recognized primarily as an Orientalist painter within the French academic sphere, Ralli never fully detached from his Greek roots. His family background, his connection to the Greek monarchy (via King Otto's initial support), and his choice to sometimes depict Greek Orthodox subjects demonstrate an ongoing engagement with his heritage. Paintings set in Greek monasteries or churches stand apart from his more typical Orientalist fare, showcasing a different facet of Eastern Mediterranean culture.

This duality makes Ralli an interesting figure in the context of 19th-century Greek art. While many Greek artists of the period, such as Nikolaos Gyzis (1842-1901) or Georgios Jakobides (1853-1932), studied in Munich and were influenced by German academicism and genre painting (the "Munich School" of Greek art), Ralli pursued a Parisian path. Yet, he remained connected to Greece and is considered one of the most important Greek painters of his generation. His international success brought recognition to Greek artists operating on the wider European stage. His work represents a distinct strand within modern Greek art, one heavily influenced by French Orientalism but retaining links to Hellenic identity.

Legacy and Unexplored Dimensions

Theodore Jacques Ralli died in Lausanne, Switzerland, on October 2, 1909 (though some sources state London). He left behind a substantial body of work that continues to be appreciated for its technical skill and evocative portrayal of 19th-century Eastern Mediterranean life. He is remembered as a leading figure of late Orientalism and a significant Greek artist with an international career.

Despite his success during his lifetime, Ralli's work, like much academic and Orientalist painting, fell out of favor with the rise of Modernism in the early 20th century. However, there has been a renewed interest in 19th-century academic and Orientalist art in recent decades, leading to a reassessment of figures like Ralli. The 2020 exhibition "Théodore Ralli: Looking East" at the Benaki Museum in Athens marked a significant moment in bringing his work back into focus, particularly within his native Greece.

While his paintings are admired for their surface beauty and detail, questions remain about deeper meanings or unexplored cultural commentary. Did his Greek background subtly inform his portrayal of Ottoman or Egyptian society? Are there hidden symbols or allegories within his carefully constructed scenes? While scholarship has primarily focused on his technique, biography, and place within Orientalism, the potential for richer interpretations, considering the complex cultural intersections of his life and work, may still exist. However, unlike artists known for overt symbolism, Ralli's work appears more grounded in detailed observation and the creation of atmosphere, aligning with the dominant aesthetic concerns of his training and chosen genre.

Conclusion: Bridging Worlds Through Art

Theodore Jacques Ralli's life and art exemplify the cultural exchanges and artistic trends of the late 19th century. Born Greek in Constantinople, trained in the academic heart of Paris, and finding inspiration in the landscapes and cultures of Egypt and the Near East, he was a truly cosmopolitan figure. His paintings, characterized by meticulous craftsmanship, sensitivity to light, and a focus on intimate genre scenes, offered European audiences captivating glimpses into worlds perceived as exotic, yet rendered with a familiar and reassuring technical mastery.

He successfully navigated the demands of the Paris Salon and the tastes of international collectors, achieving fame and recognition within the popular Orientalist movement. While subject to the critiques leveled at Orientalism regarding representation and romanticization, Ralli's work often possesses a distinct atmosphere, perhaps influenced by his personal connections to the regions he depicted. As both a key Orientalist painter and one of the most internationally prominent Greek artists of his era, Theodore Jacques Ralli occupies a unique and enduring place in the history of art, his canvases continuing to bridge worlds and invite contemplation across cultures and time.