Leonardo De Mango (1843-1930) stands as a fascinating figure in the annals of 19th and early 20th-century art, an Italian painter who dedicated much of his life and career to capturing the essence of the "Orient." His journey from Southern Italy to the bustling streets of Constantinople (now Istanbul) reflects a broader European fascination with the East, yet De Mango carved his own niche through his distinctive style and dedication to his adopted home. This article delves into the life, artistic evolution, and enduring legacy of a painter who bridged cultural divides through his evocative canvases.

Early Life and Artistic Awakening in Italy

Born in Bisceglie, a coastal town in the Apulia region of Southern Italy, in 1843, Leonardo De Mango's early life was marked by a burgeoning artistic talent that was largely self-cultivated. The rich cultural tapestry and vibrant landscapes of his native region likely provided initial inspiration. His innate abilities eventually earned him a scholarship, a crucial stepping stone that allowed him to pursue formal artistic training.

De Mango enrolled in the Naples Academy of Fine Arts (Accademia di Belle Arti di Napoli), a prestigious institution that had nurtured many of Italy's prominent artists. During his time there, he studied under influential figures such as Filippo Palizzi (1818-1899), known for his realistic depictions of animals and rural life, and Domenico Morelli (1823-1901), a leading figure in Neapolitan painting who moved from Romanticism towards a more symbolic and historical style. Morelli, in particular, was known for his dramatic compositions and rich color palettes, often drawing on historical and literary themes, including Orientalist subjects.

Despite learning from such esteemed masters, De Mango reportedly grew dissatisfied with the rigid academicism prevalent in the Neapolitan art scene. This restlessness and a desire for a different artistic environment may have prompted him to seek further development elsewhere, with some accounts suggesting a period of study or artistic exploration in Venice. Venice, with its own historical ties to the East and a rich artistic heritage exemplified by masters like Titian and Tintoretto, could have offered a different perspective and further fueled his burgeoning interest in exotic locales.

The Lure of the East: A New Artistic Horizon

The mid-19th century was a period of intense European interest in the cultures and landscapes of North Africa, the Middle East, and the Ottoman Empire, a phenomenon broadly termed "Orientalism." Artists, writers, and scholars were drawn to what they perceived as exotic, vibrant, and historically rich societies. Leonardo De Mango was no exception to this allure. In 1874, he made a pivotal decision to move to Syria, then part of the vast Ottoman Empire.

His time in Syria was transformative. De Mango immersed himself in the local environment, traveling and working in cities like Aleppo, Damascus, and Antioch. These ancient urban centers, with their bustling souks, historic architecture, and diverse populations, provided a wealth of subject matter. He meticulously studied the local customs, the vibrant colors of traditional attire and textiles, and the unique quality of light that bathed the landscapes. This period was crucial for developing his observational skills and his ability to translate the sensory richness of the East onto canvas. He sought to capture not just the visual appearance but also the atmosphere and spirit of the places he encountered.

This immersion allowed him to move beyond superficial exoticism, striving for a more nuanced understanding of the cultures he depicted. His works from this period began to reflect a deeper engagement with the daily life, traditions, and people of the Levant.

Constantinople: An Adopted Home and Artistic Zenith

After nearly a decade of absorbing the sights and sounds of Syria and other parts of the Levant, Leonardo De Mango made another significant move. In 1883, he settled in Constantinople, the magnificent capital of the Ottoman Empire. This city, straddling Europe and Asia, was a cosmopolitan melting pot, a vibrant hub of culture, trade, and art. For De Mango, it would become his home for the remainder of his life and the primary inspiration for his mature artistic output.

In Constantinople, De Mango established himself as one of the leading Western artists, part of a community of European painters, often referred to as "Levantine artists" or "Pera painters," who were captivated by the city. He became an active participant in the local art scene, exhibiting his works regularly, including at the Pera painting salons, which were important venues for showcasing contemporary art in the Ottoman capital. His talent did not go unnoticed, and he also took on a teaching role at the School of Fine Arts in Istanbul (Sanayi-i Nefise Mektebi), contributing to the education of a new generation of Ottoman artists. This institution was founded by Osman Hamdi Bey (1842-1910), a pioneering Ottoman painter, archaeologist, and museum curator, who himself created iconic Orientalist works from an insider's perspective.

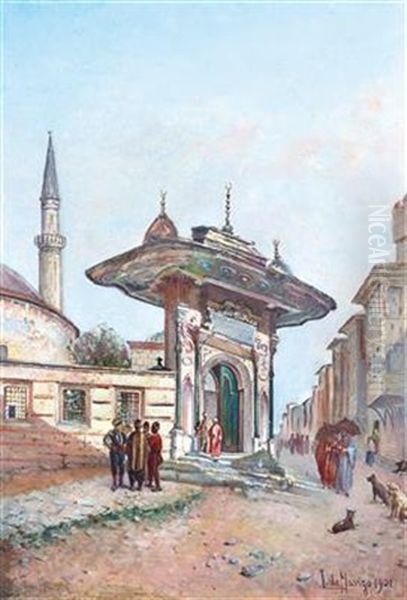

De Mango's studio in Pera, the European quarter of Constantinople, became a hub for his creative endeavors. He produced a prolific body of work depicting the city's iconic landmarks, its bustling street scenes, its diverse inhabitants, and the serene landscapes of the Bosphorus. He captured the grandeur of mosques like Hagia Sophia, the lively atmosphere of the Grand Bazaar, and the quiet dignity of everyday people.

Artistic Style: A Fusion of Realism and Romantic Orientalism

Leonardo De Mango's artistic style is firmly rooted in 19th-century Orientalism, yet it possesses individual characteristics that distinguish his work. He masterfully combined a strong foundation in Italian academic realism with a romantic sensibility suited to his exotic subjects.

His paintings are characterized by a keen attention to detail, evident in his rendering of architecture, traditional costumes, and the varied textures of market goods or natural landscapes. He had a particular skill for capturing the unique interplay of light and shadow in the Eastern Mediterranean, from the dazzling sunlight of a Cairo street to the softer, more diffused light of an Istanbul interior. This sensitivity to light and atmosphere imbued his paintings with a palpable sense of place.

De Mango's palette was rich and vibrant, reflecting the colorfulness he observed in the East. He employed warm earth tones, brilliant blues, and striking reds to convey the visual splendor of his subjects. While his work often depicted picturesque scenes and traditional ways of life, he generally avoided the more sensationalized or overly stereotyped portrayals common in some Orientalist art. Instead, there is often a sense of empathy and genuine observation in his depictions of people and their daily activities.

He was versatile in his choice of media, though he showed a preference for oil painting. Some sources also indicate his proficiency with pastels and quill pens, suggesting a broader range of artistic practice that likely included sketches and studies which informed his more finished oil paintings. His compositions were carefully constructed, often leading the viewer's eye through bustling marketplaces or into serene landscapes, creating a sense of depth and engagement.

While clearly an Orientalist, De Mango's long-term residency in the East, particularly in Istanbul, allowed for a more intimate and sustained engagement with his subjects than that of artists who made only fleeting visits. This prolonged immersion likely contributed to a more nuanced and less purely "exoticizing" gaze in many of his works, even as they catered to Western tastes for Oriental scenes.

Notable Works: Windows into a Vanished World

Leonardo De Mango's oeuvre is extensive, and several works stand out as representative of his talent and thematic concerns.

One of his most significant early Orientalist pieces is The Oriental Storyteller (also known as Cantastorie of the Orient), painted around 1882, likely during or shortly after his Syrian period. This work captures a quintessential scene of Eastern life: a storyteller captivating an audience in a public square. The painting showcases De Mango's ability to render diverse characters, intricate details of costume and setting, and a lively, engaging atmosphere.

Le Fumeur de Chibouk (The Chibouk Smoker) is another characteristic work, depicting a figure in quiet contemplation while smoking a traditional long-stemmed pipe. Such genre scenes, focusing on moments of leisure or daily ritual, were popular among Orientalist painters and their patrons.

His Istanbul period yielded a wealth of cityscapes and genre scenes. Paintings depicting the Bosphorus, with its caiques and waterside villas, views of the Golden Horn, and scenes from within the city's historic quarters, are numerous. Works like Turkish Camel Caravan and Turkish Shepherd with Flock illustrate his interest in the traditional, pastoral aspects of life that could still be found in and around the bustling metropolis. His depictions of iconic structures, such as a painting titled Hagia Sophia, demonstrate his skill in architectural rendering and capturing the grandeur of these historic sites.

Other titles attributed to him, such as The Nile and Bustling Life in Cairo, suggest that his travels and artistic interests extended beyond Syria and Turkey, encompassing Egypt as well. These paintings would have further catered to the European appetite for scenes from across the "Orient." Each work, whether a grand cityscape or an intimate genre scene, served as a visual document, preserving moments and vistas of a world undergoing rapid change.

Context and Contemporaries: De Mango in the World of Orientalism

Leonardo De Mango operated within a vibrant and diverse international art scene, particularly concerning Orientalism. This movement, which peaked in the 19th century, included artists from across Europe and America.

In France, Jean-Léon Gérôme (1824-1904) was a dominant figure, known for his highly detailed and often dramatic academic paintings of Middle Eastern and North African scenes. Eugène Delacroix (1798-1863), an earlier pioneer, had brought a Romantic fervor to his depictions of North Africa. Other French Orientalists included Alexandre-Gabriel Decamps (1803-1860) and Eugène Fromentin (1820-1876).

British artists also made significant contributions. John Frederick Lewis (1804-1876) was celebrated for his meticulously detailed watercolors and oil paintings of life in Cairo, where he lived for many years. David Roberts (1796-1864) was famous for his topographical views and architectural studies of Egypt and the Holy Land.

From the German-speaking world, artists like Ludwig Deutsch (1855-1935) and Rudolf Ernst (1854-1932), both Austrian, produced highly polished and popular Orientalist scenes, often focusing on guards, scholars, and opulent interiors.

Italy, too, had its share of Orientalist painters. Alberto Pasini (1826-1899) was a notable contemporary of De Mango, renowned for his vibrant and detailed depictions of Persia, Turkey, and Arabia. Pasini, like De Mango, spent considerable time in the East and achieved international recognition. Another Italian, Fausto Zonaro (1854-1929), became the court painter to Sultan Abdul Hamid II in Constantinople, occupying a more official position than De Mango. Zonaro's work often depicted Ottoman court life, military parades, and historical events, providing a different, often grander, perspective on the Ottoman capital.

Within Constantinople itself, De Mango would have been aware of the work of Ottoman painters like the aforementioned Osman Hamdi Bey, who, unlike many Western Orientalists, painted his own culture with an insider's knowledge and often with a critical or intellectual eye, exploring themes of Ottoman identity and tradition in a changing world. The presence of such diverse artists created a dynamic artistic environment in Constantinople, where different perspectives on the "Orient" coexisted and sometimes intersected. De Mango's contribution was that of a long-term resident, deeply familiar with the city, yet still an Italian observing and interpreting it through his own cultural lens. His contemporaries back in Italy, like Giovanni Fattori (1825-1908) of the Macchiaioli group or the realist Antonio Mancini (1852-1930), were exploring very different artistic paths, highlighting the distinct choices De Mango made in dedicating his career to Orientalist themes.

Challenges, Later Life, and Enduring Poverty

Despite his artistic productivity and his recognized position within the Istanbul art community, Leonardo De Mango's life was reportedly marked by persistent financial struggles. The romantic image of the successful expatriate artist often belies the economic realities many faced. De Mango, born into a family of modest means, seems to have never fully escaped a degree of poverty.

This financial insecurity persisted throughout his long career in Constantinople. While he sold paintings and taught, it appears he did not achieve the level of commercial success that would have guaranteed a comfortable life. This might be partly due to his status; unlike Fausto Zonaro, he was not an official court painter with a regular stipend. He relied on private sales, commissions, and his teaching income, which could be precarious.

In his later years, De Mango is said to have lived in the house of a Venetian merchant in Istanbul, perhaps indicating a reliance on the charity or support of patrons or friends. The image of an aging artist, still dedicated to his craft but facing economic hardship, is a poignant one.

Leonardo De Mango passed away in Istanbul in 1930, at the age of 87. His long life had spanned a period of immense change in both Europe and the Ottoman Empire, which itself had ceased to exist, replaced by the Republic of Turkey. Tragically, reflecting his lifelong financial struggles, he was reportedly buried in a pauper's grave, a humble end for an artist who had contributed so much to the visual record of his adopted city.

Legacy and Art Historical Significance

Leonardo De Mango's legacy is primarily that of a dedicated and skilled Orientalist painter who provided a rich visual account of the Middle East, particularly Constantinople, during a pivotal era. His works are valued not only for their artistic merit—their vibrant colors, detailed execution, and atmospheric qualities—but also as historical documents. They offer glimpses into the daily life, architecture, and cultural fabric of societies that were on the cusp of profound transformation.

While he may not have achieved the same level of international fame as some of his Orientalist contemporaries like Gérôme or Lewis during his lifetime, his paintings are now sought after by collectors and museums, particularly those specializing in Orientalist art or the art of the Ottoman period. His long residency in Istanbul distinguishes him from many "visiting" Orientalists, lending his work a quality of sustained observation and familiarity.

De Mango's art contributed to the Western European visual understanding of the "Orient," participating in a broader cultural dialogue, however complex and sometimes problematic, between East and West. His paintings, filled with light, color, and human activity, continue to evoke the allure and dynamism of the lands he depicted. He remains an important figure for understanding the role of Italian artists within the Orientalist movement and the cosmopolitan art world of late Ottoman Istanbul. His life and work underscore the profound impact that cross-cultural encounters can have on artistic creation, leaving behind a legacy that continues to fascinate and inform.

Conclusion

Leonardo De Mango's journey from the shores of Italy to the heart of the Ottoman Empire was one of artistic passion and unwavering dedication. He embraced the "Orient" not as a fleeting subject but as a lifelong inspiration, immersing himself in its cultures and translating his experiences into a rich body of work. Through his detailed and evocative paintings, he captured the vibrant street scenes, the majestic architecture, and the everyday life of Syria and, most notably, Constantinople. Despite facing personal hardships, including persistent poverty, De Mango left an indelible mark as a significant Orientalist painter. His canvases serve as luminous windows into a bygone era, reflecting both the European fascination with the East and the unique artistic vision of a man who found his true calling far from his native land. His work remains a testament to the power of art to bridge worlds and preserve the beauty of human experience across cultural divides.