Federico Fiori, known to posterity as Federico Barocci (or Baroccio), stands as a pivotal figure in the landscape of late Italian Renaissance and early Baroque art. Born in the culturally rich city of Urbino around 1535 (though some earlier sources suggest 1526 or 1528, the later date is now more commonly accepted), he died in his hometown in 1612. His adopted surname, Barocci, likely derived from the family name, though popular lore sometimes connects his nickname "Il Baroccio" to a local term for a two-wheeled cart, perhaps hinting at a certain groundedness or regional identity. Regardless of its origin, Barocci emerged as one of the most original and influential painters of his generation, particularly active in central Italy. His unique synthesis of High Renaissance grace, Mannerist elegance, and a burgeoning Baroque emotionalism, combined with an innovative approach to color and light, carved a distinct path that deeply impacted subsequent artists, most notably Peter Paul Rubens.

Barocci's artistic journey began within his own family. His father, Ambrogio Barocci, was a sculptor of some local repute, providing Federico with an initial immersion in the world of plastic arts. This early exposure to three-dimensional form may have subtly informed his later painterly attention to volume and structure. However, his primary artistic education commenced under the guidance of Battista Franco, a painter active in Urbino who himself had trained in Rome and absorbed the powerful influence of Michelangelo. This connection provided Barocci with an indirect link to the monumental figurative tradition of the High Renaissance. Urbino itself, though past its absolute zenith under Duke Federico da Montefeltro, remained a significant artistic center, forever marked by the legacy of its most famous son, Raphael. This environment undoubtedly nurtured the young Barocci's artistic sensibilities.

Roman Experiences and Formative Influences

Seeking broader horizons and deeper engagement with the artistic currents of his time, Barocci traveled to Rome. His first significant stay likely occurred around the mid-1550s. Rome, the epicenter of artistic innovation and patronage, offered unparalleled opportunities for study. During this period, he is known to have associated with prominent Mannerist painters, notably the brothers Taddeo Zuccari and Federico Zuccari. Working alongside them exposed him to the sophisticated, complex compositions and elegant, elongated figures characteristic of late Mannerism. This experience refined his draftsmanship and compositional skills, adding a layer of fashionable complexity to his developing style.

However, Barocci was not merely an imitator. He actively sought out the foundational masters of the earlier Renaissance. He dedicated himself to studying the works of Raphael, absorbing the harmony, clarity, and idealized grace that defined the High Renaissance ideal. The profound humanity and gentle emotionality in Raphael's figures resonated deeply with Barocci's own temperament. Equally important was his encounter with the art of Antonio Allegri da Correggio. Though Correggio worked primarily in Parma, his influence was palpable in Rome. Barocci was captivated by Correggio's mastery of soft, sfumato-like transitions, his tender sentiment, and his luminous, almost dissolving use of light and color. This influence would become a hallmark of Barocci's mature style, setting him apart from the harder linearity of many Florentine and Roman Mannerists. He also studied the Venetian masters, particularly Titian, learning from their rich colorito and expressive brushwork.

His talent did not go unnoticed. A significant commission came during a later Roman stay in the early 1560s when he was invited, alongside Federico Zuccari, to contribute decorations to Pope Pius IV's Casino (or Villa Pia) in the Vatican Gardens. This prestigious project placed him at the heart of papal patronage. Barocci executed ceiling frescoes depicting the Annunciation and the Adoration of the Magi, among other scenes. However, this Roman period was abruptly curtailed. According to his early biographer Giovanni Pietro Bellori, Barocci believed he had been poisoned by jealous rivals during a picnic. Whether an actual attempt or a manifestation of profound anxiety and ill health (he suffered from chronic stomach ailments, possibly a duodenal ulcer), the incident prompted his retreat from Rome around 1563. He returned to the relative sanctuary of Urbino, leaving the competitive environment of the metropolis behind.

Return to Urbino and Mature Career

Back in his native Urbino, Barocci established the pattern that would define the rest of his long and productive career. While he maintained connections with patrons across Italy, receiving commissions from cities like Perugia, Arezzo, Genoa, Milan, and even from Emperor Rudolf II in Prague and King Philip II of Spain, Urbino remained his primary base of operations. He became the leading painter in the Marche region, enjoying the consistent patronage of the Della Rovere Dukes, particularly Francesco Maria II. His relative isolation from the major artistic centers of Rome, Florence, and Venice allowed him to cultivate his highly personal style, synthesizing his diverse influences into something uniquely his own.

Despite suffering from recurring ill health, which often limited his working hours, Barocci was remarkably prolific. His meticulous working method, involving numerous preparatory studies, contributed to the deliberate pace of his output but ensured the high quality and refinement of his finished works. He lived a relatively secluded life, dedicated to his art and his religious faith, which deeply informed the sincere piety evident in his paintings. His workshop in Urbino became a local hub, although he did not foster a large school of direct followers in the manner of some contemporaries. Antonio Viviani ("Il Sordo") was one notable pupil. Barocci's influence spread more through the dissemination of his paintings and prints than through direct teaching on a large scale.

His reputation grew steadily. He was highly esteemed by artists and connoisseurs alike. Annibale Carracci, a key figure in the Bolognese school and the development of Baroque classicism, admired Barocci's work. Bellori, writing later in the 17th century, praised his unique ability to blend Lombard color and grace (referring to the influence of Correggio) with the compositional strength associated with Raphael and the central Italian tradition of disegno. Barocci successfully navigated the demands of Counter-Reformation art, creating images that were theologically sound, emotionally engaging, and accessible to the faithful, without sacrificing artistic sophistication.

Artistic Style and Technique: Color, Light, and Emotion

Federico Barocci's style is characterized by a unique confluence of tenderness, dynamism, and luminosity. He moved away from the often artificial elegance and intellectual complexity of High Mannerism towards a more naturalistic observation and heartfelt emotional expression, yet without embracing the stark realism later championed by Caravaggio. His art represents a bridge, retaining the grace of the Renaissance while anticipating the emotional intensity and visual dynamism of the Baroque.

Color is perhaps the most distinctive element of Barocci's art. He employed a palette characterized by soft, pastel-like hues – shimmering pinks, vibrant blues, pale yellows, and gentle greens – often blended with remarkable subtlety. His use of cangiante (shot colors, where drapery shifts hue in light and shadow) adds vibrancy and complexity. This approach contrasts sharply with the more saturated primary colors of the High Renaissance or the sometimes acidic tones of Mannerism. His color harmonies are delicate and atmospheric, contributing significantly to the overall mood of his paintings. The influence of Correggio and Venetian painters like Titian is evident, but Barocci developed a personal chromatic sensibility that was lighter and more ethereal.

Light plays a crucial role in his compositions. Barocci masterfully employed chiaroscuro, but his approach differs from the dramatic tenebrism of Caravaggio. Barocci's light is softer, more diffused, often appearing to emanate from within the figures or suffuse the scene with a gentle, spiritual glow. It defines form softly, creates atmosphere, and directs the viewer's eye, highlighting key emotional moments. His shadows are transparent and luminous, never heavy or opaque. This handling of light contributes to the characteristic warmth and intimacy of his work.

Compositionally, Barocci favored dynamic arrangements, often employing diagonal thrusts and swirling movements that activate the picture plane. While influenced by Mannerist complexity, his compositions generally possess an underlying clarity and emotional focus. Figures are often depicted in graceful, sometimes complex poses, but these feel motivated by the narrative and emotional content rather than being purely stylistic affectations. He achieved a balance between Mannerist dynamism and a more naturalistic rendering of figures and space, anticipating the compositional energy of the Baroque.

Emotional expression, or affetti, is central to Barocci's art. He excelled at conveying tender sentiments, profound piety, and moments of spiritual ecstasy. His Madonnas are gentle and maternal, his saints contemplative or rapturous, his Christs both divine and vulnerably human. He achieved this through subtle facial expressions, gestures, and the overall atmosphere created by color and light. This focus on relatable human emotion aligned perfectly with the Counter-Reformation's call for art that could inspire devotion and empathy in the viewer.

The Preparatory Process: A Foundation of Mastery

A key aspect of Barocci's practice, and one that reveals much about his artistic thinking, was his extraordinarily thorough preparatory process. He was one of the first artists to systematically use colored pastels and oil sketches as integral parts of developing his final compositions. His surviving drawings, numbering in the thousands, attest to this meticulous approach.

His process typically involved several stages. He would begin with quick compositional sketches, often in pen and ink or chalk, to establish the overall arrangement. He then studied individual figures and details from life, creating numerous drawings in black and white chalk, often on colored paper, to refine poses and anatomy. Crucially, he then moved to studies in colored chalks (pastels) and oil sketches (bozzetti or modelli). These allowed him to work out the complex harmonies of color and the effects of light and shadow before committing to the final canvas or panel. The pastels, in particular, enabled him to achieve the soft, blended effects characteristic of his finished paintings. The oil sketches, often quite painterly and free, helped establish the tonal structure and overall impact. This multi-layered process allowed for continuous refinement and ensured that the final work was meticulously planned yet retained a sense of vibrancy and immediacy. This systematic use of color studies was innovative for its time and influenced later artists who adopted similar preparatory methods.

Key Works: Masterpieces of Sentiment and Light

Barocci's oeuvre consists primarily of religious subjects, particularly altarpieces, along with some portraits and mythological scenes. Several works stand out as defining examples of his style and contribution.

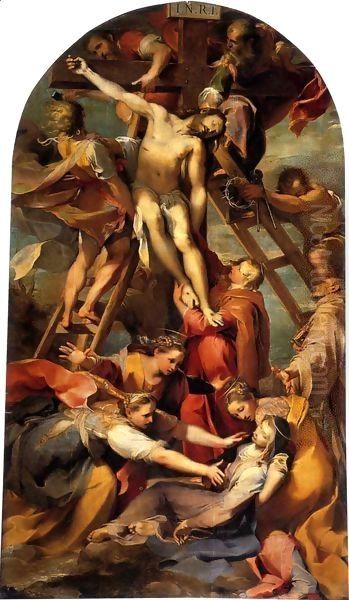

The Deposition (1567-69), painted for the Cathedral of San Lorenzo in Perugia, was one of his first major commissions after returning from Rome. It established his reputation outside Urbino. The work is notable for its complex, swirling composition, centered on the dramatically lit body of Christ being lowered from the cross. The intense grief of the surrounding figures, particularly the swooning Virgin Mary, is conveyed with palpable sincerity. The use of vibrant, almost iridescent colors and dynamic poses shows Mannerist influences, but the overall emotional impact points towards the Baroque.

His Madonna del Popolo (Madonna of the People), completed around 1579 for a confraternity in Arezzo and now housed in the Uffizi Gallery, Florence, is often considered one of his masterpieces. The painting depicts the Virgin Mary interceding with Christ on behalf of humanity, represented by a diverse group of figures below, including wealthy patrons and the poor. It masterfully blends divine grace with observations of everyday life. The composition is complex yet clear, unified by a warm, enveloping light and Barocci's signature soft color palette. It exemplifies his ability to create large-scale works that are both monumental and intimate.

The Rest on the Flight into Egypt (c. 1570-73), now in the Vatican Pinacoteca, showcases Barocci's charm and tenderness. The Holy Family is depicted pausing during their journey. Joseph offers cherries (plucked from a miraculously fruiting tree) to the Christ Child, who playfully reaches out while seated on Mary's lap. The scene is filled with naturalistic details and imbued with a sense of peaceful domesticity, rendered in soft light and delicate colors. It highlights Barocci's ability to humanize sacred subjects.

Another significant work is the Entombment (1579-82), painted for the Church of Santa Croce in Senigallia. Similar in theme to the Perugia Deposition but perhaps even more emotionally concentrated, it focuses on the moment Christ's body is laid in the tomb. The dramatic lighting, falling intensely on Christ and the grieving figures, creates a powerful sense of pathos. The rich colors and dynamic arrangement of figures contribute to the scene's emotional weight.

The Annunciation (c. 1582-84), also in the Vatican Pinacoteca, is celebrated for its ethereal beauty. The Archangel Gabriel appears before Mary in a burst of divine light. The delicate rendering of the figures, the soft, atmospheric light, and the subtle emotional exchange between Gabriel and the humbly receptive Mary make this one of Barocci's most lyrical creations. His mastery of pastel-like hues is particularly evident here.

Commissioned by his patron Duke Francesco Maria II della Rovere for Urbino Cathedral, the Last Supper (1590-99) is a monumental work demonstrating Barocci's ability to handle complex multi-figure compositions on a grand scale. Unlike Leonardo da Vinci's iconic version focusing on the betrayal, Barocci depicts the institution of the Eucharist. The scene is imbued with spiritual intensity, illuminated by both natural and divine light sources, and filled with dynamic figures expressing a range of emotions.

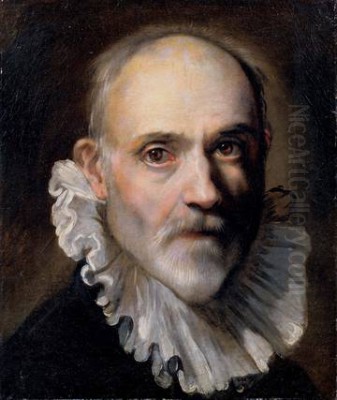

Barocci was also an accomplished portraitist, although these form a smaller part of his output. His Portrait of Francesco Maria II della Rovere (c. 1572, Uffizi/Pitti Palace, Florence) shows his ability to capture not only a likeness but also the sitter's status and personality, using his characteristic sensitivity to color and light. Other notable works include the Martyrdom of St. Vitale (1580-83, Pinacoteca di Brera, Milan), showcasing his ability to handle dramatic action, and The Circumcision (1590, Louvre, Paris), another complex altarpiece demonstrating his mature style.

Barocci as a Printmaker

Beyond his prolific output as a painter, Federico Barocci also made significant contributions to the art of printmaking. He was one of the most important Italian painters of his time to seriously engage with etching. While printmaking was often used for reproductive purposes, Barocci approached etching as an original creative medium, translating his painterly concerns into linear form.

He produced only a small number of etchings, perhaps around four major plates, but they are of exceptional quality and were highly influential. His most famous prints include The Annunciation (related to his painting but a distinct composition), St. Francis Receiving the Stigmata (also known as Il Perdono), and The Rest on the Flight into Egypt. In his etchings, Barocci employed delicate, flickering lines and subtle tonal variations, often using techniques like stippling and varied biting to achieve atmospheric effects reminiscent of his paintings and drawings. He managed to convey a sense of color and light through purely graphic means, a remarkable achievement. His prints circulated more widely than his paintings, helping to spread his artistic ideas. His innovative approach to etching influenced later printmakers, both in Italy and Northern Europe.

Influence and Legacy

Federico Barocci occupies a crucial position in the transition from the late Renaissance and Mannerism to the Baroque. While geographically somewhat removed from the main centers of artistic revolution in Rome and Bologna, his unique style had a profound impact. His emphasis on warm color, soft light, dynamic composition, and sincere emotional expression offered a compelling alternative to both the lingering artificialities of Mannerism and the stark realism of Caravaggio.

His influence is most clearly seen in the work of Peter Paul Rubens. During his Italian sojourn (1600-1608), Rubens encountered Barocci's work and was deeply impressed. He admired Barocci's vibrant color, emotional intensity, and dynamic compositions. Rubens made drawings after Barocci's paintings, absorbing lessons that he would integrate into his own powerful Baroque synthesis. The tenderness, luminosity, and painterly richness of Rubens's art owe a significant debt to Barocci's example.

In Italy, while he didn't establish a major school, his influence permeated the artistic landscape. The Carracci brothers, particularly Annibale Carracci, respected his work. Artists of the Bolognese school, such as Guido Reni and Domenichino, who sought a balance between classical form and emotional appeal, likely looked to Barocci's example, particularly his handling of grace and sentiment. Even the great Baroque sculptor Gian Lorenzo Bernini, known for his dramatic intensity and emotionalism, may have found inspiration in the expressive power of Barocci's figures. Barocci's pioneering use of pastels and oil sketches also set a precedent for later artists' preparatory practices.

His legacy lies in his ability to forge a deeply personal style that synthesized the achievements of the High Renaissance (Raphael's grace, Correggio's sfumato) and the dynamism of Mannerism (complex poses, active compositions) while infusing his work with a new level of emotional warmth and accessibility. He anticipated key elements of the Baroque – its dynamism, emotionalism, and concern with light and color – but rendered them with a unique tenderness and delicacy. He demonstrated that profound religious feeling could be expressed through beauty, grace, and relatable human emotion, making his art both spiritually resonant and aesthetically captivating.

Conclusion: A Unique Voice in Italian Art

Federico Barocci remains a somewhat unique figure in the grand narrative of Italian art. Based primarily in his native Urbino, away from the dominant artistic centers, he cultivated a highly individual style characterized by luminous color, soft light, dynamic compositions, and profound emotional sensitivity. Drawing inspiration from masters like Correggio, Raphael, and Titian, and refining his art through an innovative and meticulous preparatory process involving pastels and oil sketches, he created works that bridge the elegance of the Renaissance with the burgeoning energy and emotion of the Baroque.

Though plagued by ill health, his long career produced a significant body of work, primarily deeply felt religious paintings and altarpieces, alongside sensitive portraits and pioneering etchings. His influence, particularly on Rubens, underscores his importance. Barocci offered a path for painting that emphasized sentiment, grace, and painterly beauty, providing a vital counterpoint to other currents in late 16th and early 17th-century art. He remains celebrated for his ability to touch the viewer's heart through images of ethereal beauty and sincere human feeling, illuminated by a characteristic soulful light.