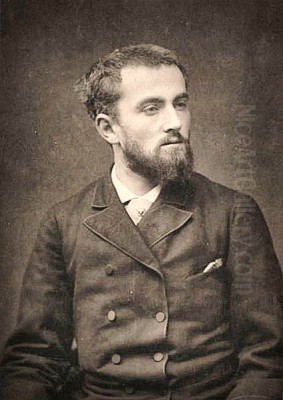

Norbert Goeneutte stands as a fascinating figure in late 19th-century French art. Born in Paris in 1854 and passing away prematurely in Auvers-sur-Oise in 1894, his relatively short career spanned a period of immense artistic ferment. Primarily recognized as a painter, etcher, and illustrator, Goeneutte navigated the vibrant Parisian art scene, closely associating with the Impressionists yet carving his own distinct path. His work, characterized by keen observation and technical skill, offers intimate glimpses into the life of Paris and the surrounding countryside, leaving behind a legacy rich in both paintings and masterful prints.

Early Life and Artistic Formation

Norbert Goeneutte's journey into the art world began in his native Paris. He enrolled at the prestigious École des Beaux-Arts, initially studying under the guidance of Isidore Pils. Pils, known for his historical and military scenes, provided a traditional academic grounding. However, Pils's death necessitated a change in tutelage, leading Goeneutte to join the studio of Henri Lehmann. Lehmann, a pupil of Ingres, represented a more rigid, classical approach to art. This formal training provided Goeneutte with a solid foundation in drawing and composition, skills that would underpin his later, more modern explorations.

Despite this academic background, the burgeoning avant-garde movements in Paris soon captured Goeneutte's attention. The strictures of the École perhaps felt limiting to his observational talents and his interest in contemporary life. He eventually left formal training, drawn towards the more dynamic and experimental atmosphere found in the cafes and studios of Montmartre, which was rapidly becoming the epicenter of artistic innovation in Paris.

Montmartre and the Impressionist Circle

The move to Montmartre proved pivotal for Goeneutte's artistic development. This bohemian quarter buzzed with creative energy, attracting painters, writers, and musicians. Goeneutte quickly integrated into this milieu, frequenting establishments like the Café de la Nouvelle Athènes, a legendary meeting place for artists. It was here and in nearby studios that he forged significant relationships with leading figures of the Impressionist movement.

He developed close friendships with artists such as Pierre-Auguste Renoir, Edgar Degas, and Édouard Manet. These interactions were crucial, exposing him to new ideas about capturing light, color, and the fleeting moments of modern life. Goeneutte wasn't just an observer; he participated actively in this circle. Famously, he served as a model for Renoir, appearing in sketches related to the iconic painting Bal du moulin de la Galette (1876), a masterpiece depicting the lively social scene of Montmartre. His presence within this group highlights his acceptance and participation in the avant-garde discussions of the time.

Other notable figures in his circle included the painter and etcher Marcellin Desboutin, who would significantly influence Goeneutte's interest in printmaking. He also knew artists like Henri Guérard, another skilled printmaker. While deeply connected to these Impressionist figures, Goeneutte maintained a degree of independence. Unlike Monet, Pissarro, or Sisley, he never officially exhibited with the Impressionist group in their independent Salons.

Painting Style and Subjects

Goeneutte's painting style reflects both his academic training and his immersion in Impressionist aesthetics. He possessed a strong command of drawing and structure, but adopted the Impressionists' interest in contemporary subject matter, looser brushwork, and the effects of light. His canvases often depict the boulevards, cafes, and daily life of Paris, capturing the atmosphere of the Belle Époque. He had a particular fondness for representing specific weather conditions and times of day, showing a sensitivity to transient effects.

His breakthrough came relatively early. In 1876, he exhibited Boulevard de Clichy under Snow at the official Paris Salon. This work, depicting a familiar Parisian scene under a blanket of snow, was well-received and demonstrated his ability to combine topographical accuracy with atmospheric sensitivity. The choice of the Salon over the Impressionist exhibitions was characteristic; Goeneutte often preferred seeking recognition through the established academic channels, even while his style aligned closely with his Impressionist friends.

His subjects ranged from bustling cityscapes and intimate interiors to portraits and landscapes. He painted scenes along the Seine, views of Montmartre, and portraits of friends and family. His palette could be subtle and tonal, particularly in his depictions of urban scenes under grey skies or snow, but could also embrace brighter colours when capturing sunnier moments or floral still lifes. He showed a particular skill in rendering textures, especially smooth, wet surfaces like rain-slicked streets, aligning him with the realistic vein that ran alongside Impressionism.

Mastery of Printmaking

While accomplished as a painter, Norbert Goeneutte achieved perhaps his most significant recognition as a printmaker. Inspired initially by his friend Marcellin Desboutin, Goeneutte embraced etching and drypoint with enthusiasm and remarkable skill. He became a leading figure in the etching revival that occurred in France during the latter half of the 19th century, a movement also championed by artists like Félix Bracquemond and Seymour Haden (though Haden was British, his influence was felt in France).

Goeneutte produced around 250 prints during his career, demonstrating exceptional technical proficiency, particularly in drypoint and aquatint. Drypoint, which involves scratching directly onto the copper plate with a sharp needle, allowed him to create lines with a rich, velvety burr, lending a unique atmospheric quality to his prints. Aquatint enabled him to achieve tonal variations, mimicking the effects of watercolour washes and enhancing the play of light and shadow in his compositions.

His prints often revisited the subjects found in his paintings: Parisian views, landscapes (especially those around Paris and later Auvers), seascapes, and intimate portraits of those close to him, including his sister and his doctor, Paul Gachet. His printmaking technique was admired by his contemporaries, and he even provided guidance to other artists, including Desboutin and Henri Guérard, sharing his expertise in the medium. His graphic work is noted for its spontaneity, elegance, and ability to capture the essence of a scene with economical yet expressive lines.

Illustration Work

Beyond painting and printmaking, Goeneutte also made contributions as an illustrator. His skills in drawing and composition lent themselves well to this field. One of his notable commissions was providing illustrations for the serialized publication of Émile Zola's novel La Terre (The Earth). Zola, a central figure in the Naturalist literary movement, often had close ties with painters who shared his interest in depicting contemporary reality, such as Manet and Degas. Goeneutte's ability to capture everyday life and character made him a suitable choice for illustrating Zola's gritty portrayal of peasant life.

He also contributed plates to publications dedicated to printmaking, such as L'Illustration Nouvelle, a periodical showcasing original etchings. His work appeared alongside prints by other prominent etchers of the day. Furthermore, he provided illustrations for Richard Lesclide's Paris à l'eau-forte in 1876, a publication celebrating the city through the medium of etching. These illustrative projects demonstrate the breadth of his artistic practice and his engagement with the publishing world of his time.

Exhibitions and Recognition

Throughout his career, Goeneutte sought recognition primarily through the official Paris Salon, the annual state-sponsored exhibition that remained the most prestigious venue for artists, despite the challenges posed by the Impressionist group shows. He exhibited regularly at the Salon from his debut in 1876 onwards, presenting paintings that often depicted scenes of Parisian life and landscapes.

His participation in the Salon indicates a desire to bridge the gap between academic acceptance and modern artistic trends. While his friends like Monet and Renoir largely abandoned the Salon after their initial rejections, Goeneutte continued to submit work there. However, his connections and style clearly placed him within the orbit of the avant-garde.

His reputation extended beyond France. Goeneutte's works, particularly his prints, were exhibited internationally, including shows in London, Rotterdam, and Venice. This indicates a growing appreciation for his unique blend of realism and Impressionist sensibility, and especially for his technical mastery as a printmaker. Today, his works are held in major public collections, including the New York Public Library and the Musée Pissarro in Pontoise, which holds a significant collection related to artists who worked in the region.

The Auvers-sur-Oise Period

In 1891, seeking respite and perhaps a change of scenery due to declining health, Goeneutte moved from the bustle of Paris to the quieter village of Auvers-sur-Oise. This picturesque village on the Oise river, north of Paris, had long been an important center for landscape painters. Charles-François Daubigny, a precursor of Impressionism, had lived and worked there, attracting many other artists.

Auvers held a particular significance in the art world. Camille Pissarro and Paul Cézanne had worked there together in the 1870s. Most famously, Vincent van Gogh spent the last dramatic months of his life in Auvers in 1890, under the care of Dr. Paul Gachet, an amateur artist and physician who was also a friend and supporter of many avant-garde painters, including Goeneutte himself. Goeneutte arrived shortly after Van Gogh's death but became part of the artistic circle around Dr. Gachet.

During his time in Auvers, Goeneutte continued to paint and make prints, focusing on the local landscape, the river Oise, and village scenes. His works from this period often possess a serene, sometimes melancholic quality. He engaged in plein air painting, capturing the specific light and atmosphere of the Vexin region. His presence in Auvers places him alongside the legacy of Daubigny, Pissarro, Cézanne, and Van Gogh, artists who were drawn to the village's simple beauty and tranquil environment.

Later Life and Legacy

Norbert Goeneutte's time in Auvers-sur-Oise was marked by deteriorating health. He suffered from tuberculosis, a common and often fatal disease in the 19th century. Despite his illness, he continued to work as much as his strength allowed. His dedication to his art remained unwavering until the end.

He passed away in Auvers in 1894, at the young age of 40. His premature death cut short a promising career that had already yielded a significant body of work. Although his name might not be as universally recognized as those of his friends Renoir or Degas, Goeneutte holds an important place in the history of French art of the period.

His legacy lies in his sensitive portrayal of Parisian life and landscapes, his technical brilliance as a printmaker, and his unique position straddling the academic world and the Impressionist avant-garde. He is often seen as a bridge figure, incorporating modern sensibilities into a framework still rooted in careful observation and traditional skill. His prints, in particular, are highly regarded for their artistry and technical innovation, contributing significantly to the etching revival. Goeneutte's work offers a valuable perspective on the artistic diversity of the Impressionist era, reminding us that the period was populated by many talented individuals who pursued their own paths alongside the movement's giants. His art continues to be appreciated for its charm, intimacy, and skillful execution.

Conclusion

Norbert Goeneutte remains a compelling artist whose work merits continued attention. As a painter, he captured the essence of late 19th-century Paris and the French countryside with sensitivity and skill. As a printmaker, he demonstrated exceptional mastery of etching and drypoint, contributing significantly to the graphic arts of his time. His close association with the Impressionists, combined with his independent exhibition strategy, highlights the complex dynamics of the Parisian art world. Though his life was tragically short, Goeneutte left behind a rich and varied oeuvre that secures his position as an important and distinctive voice within the vibrant artistic landscape of the Impressionist era. His works endure as testaments to his keen eye, technical finesse, and dedication to capturing the world around him.