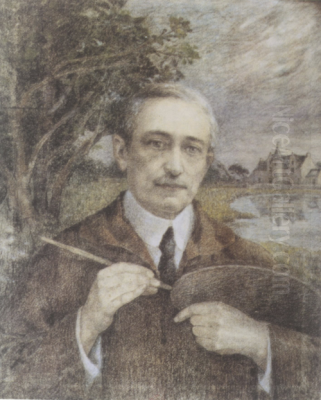

Ferdinand Loyen du Puigaudeau stands as a distinctive figure within the vibrant landscape of late 19th and early 20th-century French art. Primarily associated with Post-Impressionism and the Pont-Aven School, he carved a unique niche for himself through his captivating depictions of light, particularly the fleeting effects of twilight, moonlight, and artificial illumination. While perhaps less globally renowned during his lifetime than some contemporaries, his work possesses a poetic sensitivity and technical brilliance that has earned him growing recognition and appreciation in the decades since his death. His life, marked by both artistic camaraderie and periods of profound isolation, reflects the complexities of a painter dedicated to capturing the ephemeral beauty of the world around him, especially the landscapes and traditions of Brittany.

Early Life and Artistic Awakening

Born in Nantes on April 4, 1864, Ferdinand du Puigaudeau hailed from an affluent, aristocratic background. His early life provided a foundation of culture, though his path towards becoming a painter was not entirely conventional. Encouragement came from his uncle, Henri de Chateaubriand, who fostered his nascent artistic interests. His formal education was traditional for his class, involving studies at various boarding schools stretching from Paris to Nice. However, his true artistic education began not in the established academies, but through independent study and travel.

In 1882, seeking to hone his skills and broaden his horizons, Puigaudeau embarked on journeys to Italy and Tunisia. These travels were formative, exposing him to different cultures, landscapes, and qualities of light. It was during this period of self-directed learning that he began to seriously develop his painterly technique, observing the world with a keen eye and translating his impressions onto canvas. This early emphasis on direct observation and personal experience would remain a hallmark of his approach throughout his career.

The Pont-Aven Connection

The year 1886 marked a pivotal moment in Puigaudeau's artistic development. He produced his first known, datable works during this time, signaling the beginning of his professional output. More significantly, he made his first visit to Pont-Aven, a small village in Brittany that had become a magnet for artists seeking alternatives to the academicism of Paris. This Breton village was transforming into an important center for artistic innovation, attracting painters drawn to its rustic charm, distinct culture, and dramatic coastal scenery.

In Pont-Aven, Puigaudeau entered a stimulating artistic milieu. He formed crucial relationships with key figures of the emerging Pont-Aven School, most notably Paul Gauguin and Charles Laval. Gauguin, a charismatic and revolutionary figure, was developing his Synthetist style, characterized by bold outlines, flattened forms, and expressive, non-naturalistic color. While Puigaudeau admired Gauguin and undoubtedly absorbed aspects of the prevailing atmosphere of experimentation, he never fully adopted the Synthetist aesthetic. He remained more deeply rooted in Impressionist principles, particularly the focus on capturing the effects of light and atmosphere.

His interactions extended beyond Gauguin and Laval. The Pont-Aven circle included other significant artists like Emile Bernard, who collaborated closely with Gauguin on developing Synthetism. Puigaudeau's time in Pont-Aven exposed him to these radical new ideas about form and color, as well as the growing influence of Japanese prints (Japonisme), which emphasized asymmetry, flat color planes, and decorative patterns. This environment undoubtedly enriched his artistic vocabulary, even as he forged his own distinct path. He would return to Brittany frequently, cementing his association with the region and its artistic legacy.

Artistic Style and Techniques: A Symphony of Light

Puigaudeau's style is often categorized as Post-Impressionist, but it retains strong ties to Impressionism while incorporating elements of Symbolism and, occasionally, Neo-Impressionism. His primary fascination lay in the nuanced depiction of light. He possessed an extraordinary sensitivity to the way light transformed landscapes and scenes, particularly during transitional moments – the glow of sunset, the silvery sheen of moonlight, the flickering warmth of candlelight, or the explosive brilliance of fireworks.

Unlike the high-key palette often associated with Impressionists like Claude Monet or Pierre-Auguste Renoir, Puigaudeau frequently explored lower light conditions. He became a master of the nocturne, capturing the subtle gradations of color and tone found in evening and night scenes. His sunsets are not merely records of a time of day; they are poetic evocations of mood, often rendered in warm oranges, golds, and pinks that contrast harmoniously with the deepening blues and purples of the sky and landscape. He skillfully balanced warm and cool tones, using, for example, blues and whites to depict reflections on water or ice, creating a sense of visual equilibrium.

His technique remained largely based on Impressionist brushwork – broken color, visible strokes – aimed at capturing the immediacy of perception. However, he adapted this technique to suit his subjects. In some works, particularly those depicting artificial light sources like fireworks or lanterns, his application of paint could become more distinct, almost anticipating Pointillist effects, though generally without the systematic color theory application seen in the work of Georges Seurat or Paul Signac. One notable example often cited for its Pointillist characteristics is Office du soir. His emphasis, as he reportedly stated, was on "color above all," using a rich and vibrant palette to convey both the visual reality and the emotional resonance of a scene.

Key Themes and Subjects: Brittany and Beyond

Brittany remained Puigaudeau's most enduring source of inspiration. He was captivated by the region's rugged coastline, its ancient traditions, and the daily lives of its people. His canvases frequently depict Breton landscapes, from tranquil harbors and coastal villages to rural scenes featuring windmills and farms. He was particularly drawn to the region's cultural life, painting numerous scenes of local festivals, processions (pardons), and fairs. These works often highlight his fascination with light, showcasing torchlit parades, bonfires, or fireworks illuminating the night sky and reflecting on the assembled crowds.

His depictions often feature Breton figures, especially women in traditional coiffes and attire, integrated naturally into their surroundings. These figures are rarely individualized portraits but rather serve as elements within a larger composition, contributing to the overall atmosphere and sense of place. Works like Breton Village by the Sea exemplify his ability to combine landscape, local color, and his characteristic handling of light.

While Brittany was central, Puigaudeau also painted elsewhere. His early travels took him to Italy and Tunisia, and later in life, he spent time in Venice around 1904. His Venetian scenes, such as Venise, la nuit (Venice, Night), demonstrate his ability to apply his signature focus on nocturnal light effects to different settings, capturing the unique atmosphere of the city's canals and architecture under moonlight or gaslight. He also painted still lifes and garden scenes, like Kervaudu Garden, Climbing Roses, showcasing a sensitivity to botanical detail alongside his ever-present concern for light and color.

Representative Works

Several paintings stand out as particularly representative of Puigaudeau's style and thematic concerns. Coucher de soleil, près du Croisic (Sunset near Le Croisic) is often considered a quintessential work. It perfectly encapsulates his mastery of capturing the fleeting, incandescent light of sunset over the Breton coast. The warm, radiant colors of the sky are reflected in the water, rendered with fluid brushstrokes that convey both the brilliance of the light and the texture of the landscape.

Venise, la nuit (c. 1904) showcases his skill in translating his preoccupation with light to an urban, albeit watery, environment. The painting likely depicts a scene like the Salute church illuminated at night, capturing the interplay of architectural forms, reflections in the canals, and the ambient glow of artificial or lunar light, creating a romantic and slightly mysterious atmosphere.

Breton Village by the Sea (c. 1900) is a fine example of his Brittany scenes, possibly showing Neo-Impressionist influences in the application of color to depict the shimmering light on the water and the village architecture. It conveys the peaceful rhythm of coastal life, bathed in the clear light characteristic of the region.

Kervaudu Garden, Climbing Roses offers a glimpse into a more intimate subject. While still concerned with the play of light on surfaces, this work highlights his appreciation for nature's forms and colors on a smaller scale, likely depicting the garden of the manor he would later inhabit. These works, among many others, demonstrate his consistent focus on light, atmosphere, and the beauty found in both grand landscapes and quiet corners.

Relationships with Contemporaries

Puigaudeau's artistic life was enriched by his connections with several prominent artists, although he remained somewhat independent in his stylistic development. His most significant interactions were within the Pont-Aven circle. The relationship with Paul Gauguin was formative, providing exposure to radical ideas, even if Puigaudeau ultimately charted his own course. He maintained friendships with others from this group, including Emile Bernard and Charles Laval.

Beyond Pont-Aven, Puigaudeau cultivated other important artistic friendships. He was notably close to Edgar Degas, the renowned Impressionist master known for his depictions of modern life, particularly dancers and racehorses. Degas respected Puigaudeau's work and famously nicknamed him "the Hermit of Kervaudu," alluding to the painter's later reclusive life. This connection highlights Puigaudeau's standing among established figures, even if he operated somewhat outside the main Parisian Impressionist circles.

He also associated with Belgian artists, including the Neo-Impressionist Theo van Rysselberghe and the Symbolist James Ensor. These connections suggest an engagement with broader European artistic currents beyond France, particularly Symbolism and advanced approaches to color theory. Van Rysselberghe's refined Pointillism and Ensor's often macabre and fantastical imagery represent different facets of the era's artistic explorations.

It is important to note that while Puigaudeau operated within the broader Impressionist and Post-Impressionist era, there is no documented evidence of direct personal contact or close collaboration with figures like Claude Monet or Paul Cézanne. While he undoubtedly knew their work and shared certain Impressionist roots, his social and artistic orbit centered more directly on the Pont-Aven group and figures like Degas. His dealings with the art dealer Paul Durand-Ruel, who was instrumental in promoting Monet, Renoir, Degas, and others, were primarily commercial and ultimately ended in dispute, further distinguishing his path from some of the core Impressionists represented by the gallery. His contemporaries also included figures like Vincent van Gogh, another towering Post-Impressionist figure, though again, no direct link is established.

Later Life, Challenges, and Seclusion

The early 20th century brought significant changes and challenges for Puigaudeau. In 1907, he moved his family into the Manoir de Kervaudu, an isolated estate near Le Croisic in Brittany. This move marked the beginning of a period of increasing seclusion. While the tranquil setting provided ample inspiration for his painting, particularly garden scenes and views of the surrounding countryside, it also deepened his isolation from the wider art world. It was during this time that Degas bestowed upon him the "Hermit of Kervaudu" nickname.

Financial difficulties plagued Puigaudeau throughout much of his later life. A contract dispute with the influential dealer Paul Durand-Ruel around 1904 had already caused setbacks, forcing a temporary return to Batz-sur-Mer. Later, plans for a major exhibition of his work in New York fell through, dealing a significant blow to both his finances and his morale. These professional disappointments, coupled with his isolation, contributed to periods of depression.

Like many artists of his generation, Puigaudeau struggled with personal demons. In his later years, his isolation and depression were compounded by increasing reliance on alcohol. Despite these hardships, he continued to paint, producing works that retained his characteristic sensitivity to light and atmosphere. His dedication to his art remained steadfast, even as his connection to the bustling art centers waned. Ferdinand du Puigaudeau died in Le Croisic on September 19, 1930, relatively unrecognized by the broader public at the time.

Legacy and Posthumous Recognition

Despite the challenges and relative obscurity he faced during his later years, Ferdinand du Puigaudeau's artistic legacy has steadily grown since his death. He is now recognized as a significant and highly individual painter within the Post-Impressionist movement, particularly associated with the Pont-Aven School's later phase. His unique contribution lies in his poetic and masterful rendering of light effects, especially nocturnes and twilight scenes, which few contemporaries explored with such dedication and sensitivity.

His work is admired for its technical skill, its evocative atmosphere, and its lyrical depiction of Brittany. He successfully synthesized Impressionist techniques with a Symbolist sensibility, creating paintings that are both visually captivating and emotionally resonant. His focus on specific, often ephemeral moments – the glow of a sunset, the sparkle of fireworks, the quietude of a moonlit night – gives his work a timeless appeal.

Today, Puigaudeau's paintings are held in the collections of major international museums, including the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York, the Musée d'Orsay in Paris, the Tate in London, and numerous regional museums in France, particularly in Brittany. His work is sought after by collectors, and scholarly interest in his life and art continues to grow. He is acknowledged not just as a follower of Gauguin, but as an independent artist who absorbed influences while developing a highly personal vision.

Conclusion

Ferdinand du Puigaudeau's journey as an artist was one of dedicated exploration, focused intently on the interplay of light, color, and atmosphere. From his early self-directed studies to his engagement with the avant-garde circles of Pont-Aven, and finally to his secluded years at Kervaudu, his artistic compass remained fixed on capturing the transient beauty of the world, particularly the landscapes and traditions of Brittany illuminated by his signature light. Though marked by personal struggles and a lack of widespread fame during his lifetime, his work endures, celebrated for its poetic vision, technical finesse, and unique place within the rich tapestry of Post-Impressionist art. He remains a painter whose canvases invite viewers to pause and appreciate the subtle magic of light in its myriad forms.