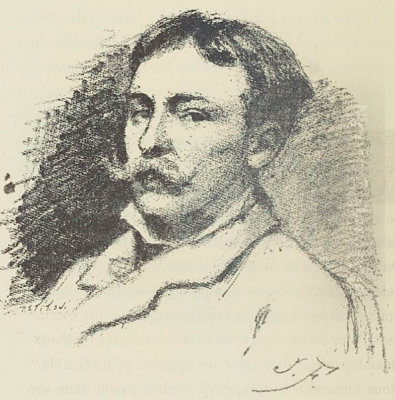

José Frappa stands as a notable figure in late 19th-century French art, a painter whose canvases captured the vibrant tapestry of Parisian society, the solemnity of religious life, and the nuanced expressions of the human condition. Born in a period of artistic transition, Frappa navigated the established Salon system while developing a distinctive style rooted in realism, often infused with a narrative depth that invited viewers into the scenes he meticulously crafted. His journey from provincial France to the heart of the Parisian art world is a testament to his dedication and talent, leaving behind a body of work that continues to offer insights into his era.

From Silk Design to Artistic Pursuits

Born on April 18, 1854, in Saint-Étienne, a city in eastern France known for its industrial prowess, particularly in coal mining and ribbon making, José Frappa's early life was not immediately directed towards the fine arts. His family was engaged in commerce, reportedly running a grocery store, and his initial professional path led him into the local silk trade as a designer. This early exposure to design, pattern, and the tactile qualities of fabric may have subtly informed his later artistic sensibilities, particularly his attention to detail in costume and setting.

However, the allure of painting proved stronger than the demands of the silk industry. By 1872, at the age of eighteen, Frappa made a decisive shift, enrolling in the École des Beaux-Arts in Lyon. This institution was a significant regional center for artistic training, and it was here that Frappa began to formally hone his skills. His education in Lyon laid the foundational techniques and academic discipline that would underpin his future career, exposing him to the classical traditions and rigorous drawing practices that were hallmarks of French art education at the time.

Formative Influences and Academic Training

At the École des Beaux-Arts in Lyon, and subsequently likely in Paris, Frappa studied under several influential masters who shaped his artistic development. Among his teachers were Isidore Pils (1813-1875), Charles Comte (1820-1884), and notably, Jehan-Georges Vibert (1840-1902), often referred to as Jean-Georges Vibert. Each of these artists brought distinct strengths and thematic preferences that would resonate in Frappa's own work.

Isidore Pils was known for his historical and military scenes, often imbued with a sense of realism and pathos, such as his famous "Rouget de Lisle Singing La Marseillaise." Charles Comte, a painter of historical genre scenes, often depicted moments from French history with meticulous attention to period detail. However, it was perhaps Jehan-Georges Vibert whose influence was most discernible in certain aspects of Frappa's oeuvre. Vibert was celebrated for his highly detailed, often humorous or satirical, genre paintings depicting cardinals and other clergy in everyday, sometimes undignified, situations. These "cardinal paintings" were immensely popular, and Frappa would later explore similar ecclesiastical themes, though often with a more serious or observational tone.

The academic training Frappa received emphasized strong draftsmanship, balanced composition, and a polished finish, all characteristics visible in his mature works. This period of intense study equipped him with the technical proficiency necessary to compete in the demanding Parisian art world.

The Parisian Art Scene and Salon Success

Like many ambitious artists of his generation, José Frappa was drawn to Paris, the undisputed capital of the art world in the 19th century. He established himself in the city and began the challenging process of building a reputation. The primary avenue for recognition and commercial success was the Paris Salon, the official art exhibition of the Académie des Beaux-Arts. To have a work accepted and favorably reviewed at the Salon could launch an artist's career.

Frappa made his Salon debut in 1875 with a painting titled Le Violoniste (The Violinist), showcasing his early interest in genre subjects and character studies. His breakthrough came shortly thereafter, in 1876, when he exhibited two significant works: Le Marché aux Fleurs (The Flower Market) and L'Antichambre du Pape (The Pope's Antechamber). The Flower Market, a vibrant depiction of a bustling Parisian scene, earned him an honorable mention, a significant early acknowledgment of his talent. This painting captured the lively atmosphere of the city, filled with figures and colorful blooms, demonstrating his skill in complex compositions and his keen eye for contemporary life.

L'Antichambre du Pape, also from 1876, signaled another important thematic direction for Frappa: scenes of clerical life. This work, likely influenced by his studies with Vibert, depicted the waiting room of the Pope, populated by various figures, hinting at the hierarchies and human dramas within the ecclesiastical world. These early successes at the Salon established Frappa as a painter of note, capable of tackling diverse subjects with skill and insight.

Artistic Style and Thematic Concerns

José Frappa's artistic style is generally characterized as Realism, though it often incorporated elements of academic polish and narrative genre painting. He was a keen observer of human behavior and social settings, and his works frequently tell a story or capture a specific moment in time with clarity and detail. His figures are rendered with anatomical accuracy, and he paid considerable attention to costume, setting, and the interplay of light and shadow to create convincing and engaging scenes.

One notable influence on his style, mentioned in some sources, is the English Pre-Raphaelite painter Ford Madox Brown (1821-1893). Brown, known for his detailed realism, moralizing themes, and historical subjects, shared with Frappa an interest in narrative and a commitment to verisimilitude. While Frappa's work generally aligns more closely with French academic realism, the connection to Brown suggests an awareness of broader European artistic currents.

Frappa's thematic concerns were varied. He excelled in genre scenes, capturing everyday life in Paris, from bustling markets to more intimate domestic interiors. His depictions of women were frequent, ranging from elegant society ladies, as seen in works like Dame Élégante (Elegant Lady, 1881), to figures in more poignant social contexts. He also continued to explore religious and ecclesiastical themes, often focusing on the human element within these settings rather than purely devotional aspects. His paintings of cardinals and church interiors, while perhaps less satirical than Vibert's, still offered a glimpse into this distinct world.

Furthermore, Frappa demonstrated an interest in social issues, as evidenced by works like L'Agence des Nourrices (The Wet Nurse Agency). This painting likely depicted the bureaus where wet nurses were hired, a common practice in 19th-century France, touching upon themes of motherhood, class, and child welfare. Such subjects aligned him with the broader Realist movement's concern for depicting contemporary social realities, a path also trodden by artists like Gustave Courbet (1819-1877) and Jean-François Millet (1814-1875) in their respective domains, and later by Naturalists like Jules Bastien-Lepage (1848-1884).

Key Works and Their Significance

Beyond his early Salon successes, Frappa produced a consistent body of work that further solidified his reputation. The Flower Market (1876) remains one of his most recognized pieces, celebrated for its lively depiction of Parisian life and its skillful handling of a complex, multi-figure composition. It showcases his ability to capture the atmosphere of a specific place and time, a hallmark of successful genre painting.

The Pope's Antechamber (1876) is significant for establishing his interest in ecclesiastical subjects. These scenes, often featuring cardinals and other church officials, allowed Frappa to explore character, costume, and the intricate settings of religious institutions. While artists like Jehan-Georges Vibert often imbued such scenes with satire, Frappa's approach could vary, sometimes offering a more straightforward observation or a gentle humor.

Elegant Lady (1881) exemplifies his skill in portraiture and the depiction of contemporary fashion and society. Such works appealed to the tastes of the bourgeois art market, which favored refined and aesthetically pleasing images.

His work L'Agence des Nourrices points to a more socially conscious dimension of his art. By tackling such a subject, Frappa engaged with contemporary social practices and concerns, aligning himself with the Realist tradition of artists who sought to represent the unvarnished realities of their time. This painting would have resonated with a public increasingly aware of social issues through literature and journalism.

Later in his career, works like La Clinique des Enfants (The Children's Clinic) and La Femme au Manteau Bleu (Woman in a Blue Cape), both exhibited at the Brussels International Exposition in 1897, further demonstrate his continued engagement with human-centered narratives and contemporary life. The former, in particular, suggests an ongoing interest in themes of social welfare and the human condition.

Wider Recognition and International Presence

Frappa's success was not confined to France. From the 1880s onwards, he began to exhibit his works in London and the United States, expanding his market and international reputation. This was a common strategy for successful European artists of the period, as American and British collectors were increasingly interested in contemporary French art.

A significant moment of international recognition came in 1897 at the Brussels International Exposition. Here, Frappa exhibited two paintings, La Clinique des Enfants and La Femme au Manteau Bleu. For these contributions, he was awarded an honorary medal, a prestigious acknowledgment of his artistic merit on an international stage. Such awards were crucial for an artist's standing and marketability.

His involvement with artistic societies also played a role in his career. He became a member of the Société des Artistes Français, the organization that took over the running of the annual Salon after the French state relinquished control. He was active within this society, even serving on its executive committee. In 1904, he participated in the Salon of the Société Nationale des Beaux-Arts (a rival Salon founded in 1890 by artists like Pierre Puvis de Chavannes, Ernest Meissonier, and Auguste Rodin, seeking more liberal exhibition policies), where he was noted as being on the executive committee alongside Pierre Puvis de Chavannes (1824-1898), a highly respected figure in French art known for his monumental allegorical murals. This indicates Frappa's respected position among his peers.

Later Career, Publications, and Personal Life

Throughout the 1880s and 1890s, Frappa continued to be a productive and respected painter in Paris. His work was regularly seen at the Salons, and he maintained a steady output of genre scenes, portraits, and ecclesiastical subjects. He was part of a generation of artists who, while not revolutionary in the vein of the Impressionists like Claude Monet (1840-1926) or Edgar Degas (1834-1917), formed the backbone of the established art world, catering to the tastes of a broad public and critical establishment.

In addition to his painting, Frappa also ventured into the realm of illustration and writing. He is credited with publishing a book titled Physiologie de l'expression humaine (Physiology of Human Expression). This interest in the scientific or systematic understanding of human expression aligns with a broader 19th-century fascination with physiognomy and the visual representation of emotions, a field also explored by artists and theorists.

On a personal level, José Frappa married Madeleine Marie Auguste Frasey in 1881. The couple had a son, Jean-José Frappa (1882-1939), who would go on to become a writer, journalist, and screenwriter. This familial connection to the literary world perhaps reflects a shared intellectual environment within the Frappa household.

Despite his successes, Frappa's life was relatively short. He passed away in Paris on February 17, 1904, at the age of 49, just shy of his 50th birthday. He was buried in the Boulogne-Billancourt cemetery. His death occurred at a time when the art world was undergoing profound transformations, with Post-Impressionism, Fauvism, and early Cubism beginning to challenge established norms.

Frappa in the Context of His Time

José Frappa operated within a complex and dynamic artistic landscape. The late 19th century in Paris was a period of intense artistic debate and diversification. The dominant force for much of his early career was Academic art, championed by figures like William-Adolphe Bouguereau (1825-1905) and Jean-Léon Gérôme (1824-1904), who emphasized classical subjects, idealized forms, and a highly polished technique. Frappa's training and much of his output show an adherence to these academic standards of craftsmanship.

However, Realism, which had emerged earlier with Courbet, continued to be a powerful influence, advocating for the depiction of ordinary life and contemporary subjects. Frappa's genre scenes and social observations clearly align with this tradition. He shared this space with other successful genre painters who captured Parisian life and historical anecdotes, such as James Tissot (1836-1902), who depicted fashionable society, or even Ernest Meissonier (1815-1891) with his meticulously detailed historical genre scenes.

Simultaneously, Impressionism was revolutionizing the way artists saw and depicted the world, focusing on light, color, and fleeting moments, often painted en plein air. While Frappa was a contemporary of the Impressionists, his style remained more traditional and narrative-focused. He did not embrace their radical techniques or their emphasis on subjective perception over detailed representation. His path was more aligned with artists who found success within the Salon system by adapting Realist principles to popular themes, much like Léon Bonnat (1833-1922) did with portraiture or Alexandre Cabanel (1823-1889) with his mythological and historical paintings.

Frappa's interest in ecclesiastical scenes, particularly those featuring cardinals, places him in a specific subgenre popular in the 19th century. Artists like Jehan-Georges Vibert and Andrea Landini (1847-1935) specialized in these often anecdotal and richly detailed depictions of clerical life, which found a ready market among collectors who appreciated their technical skill and narrative charm.

Legacy and Conclusion

José Frappa's career spanned a pivotal period in art history, from the established dominance of the Salon to the dawn of modernism. He carved out a successful career as a painter of genre scenes, portraits, and ecclesiastical subjects, earning recognition both in France and internationally. His work is characterized by its skilled draftsmanship, detailed realism, and engaging narrative content.

While perhaps not an avant-garde innovator, Frappa was a talented and respected artist who captured many facets of his time. His paintings offer valuable visual documents of late 19th-century Parisian life, social customs, and the enduring human interest in storytelling through art. Works like The Flower Market and The Pope's Antechamber demonstrate his ability to create complex, lively compositions, while his socially themed paintings reveal an awareness of contemporary issues.

Today, José Frappa's paintings can be found in various public and private collections. They continue to be appreciated for their technical accomplishment and their charming, insightful depictions of a bygone era. He remains a significant representative of the artists who thrived within the rich artistic milieu of late 19th-century Paris, contributing to the diverse tapestry of French art through his dedication to realistic representation and narrative painting. His journey from a designer in the silk trade to a celebrated Parisian artist underscores a commitment to his craft that left a lasting, if sometimes overlooked, mark on the art of his time.