Charles Monginot, a notable French painter of the 19th century, carved a distinct niche for himself within the vibrant and transformative Parisian art world. Born on September 24, 1825, in Brienne-le-Château, located in the Aube department of France, Monginot's life and career spanned a period of profound artistic evolution. He passed away on September 16, 1900, in Dienville, also in Aube, leaving behind a legacy characterized by meticulous still lifes, engaging genre scenes, and a subtle absorption of emerging modern artistic currents. His journey through the art world saw him interact with some of the most pivotal figures of his time, most notably Édouard Manet, and his work reflects both a grounding in traditional techniques and an openness to new visual languages.

Early Artistic Formation and the Influence of Thomas Couture

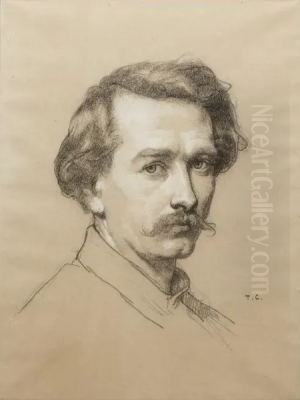

The foundation of Charles Monginot's artistic training was laid in the esteemed studio of Thomas Couture (1815-1879). Couture was a highly respected historical painter and an influential teacher, known for works like "Romans of the Decadence" (1847). His atelier attracted a diverse array of students who would go on to shape the course of art history. While Couture himself was rooted in a more academic tradition, emphasizing strong draughtsmanship and classical composition, his teaching methods also encouraged a degree of individuality and direct observation from life. This environment proved formative for Monginot.

It was within Couture's studio that Monginot encountered a fellow student who would become a lifelong associate and a significant influence: Édouard Manet (1832-1883). The interactions and shared learning experiences in this setting were crucial. Other artists who passed through Couture's studio, though perhaps not direct contemporaries or close associates of Monginot in the same way as Manet, included figures like Pierre Puvis de Chavannes (1824-1898), known for his Symbolist murals, and the German painter Anselm Feuerbach (1829-1880). The atmosphere was one of rigorous training but also burgeoning artistic exploration, setting the stage for the departures from academicism that would define the latter half of the 19th century. Monginot's family had reportedly guided him towards Couture's studio, recognizing his artistic inclinations and seeking a reputable master to hone his skills.

Navigating the Parisian Art Scene: Friendships and Collaborations

Paris in the mid-19th century was the undisputed epicenter of the art world, a crucible of tradition and revolution. Monginot established himself within this dynamic environment, living and working in the capital. His connection with Édouard Manet was particularly significant. Manet, a controversial and pioneering figure often seen as a bridge between Realism and Impressionism, valued Monginot's friendship and artistic sensibility.

This camaraderie is visibly immortalized in Manet's iconic painting, "Music in the Tuileries Gardens" (1862). In this vibrant depiction of Parisian social life, Manet included portraits of his friends and notable cultural figures. Charles Monginot is among the assembled crowd, a testament to his presence within Manet's circle. This group also included figures like the poet Charles Baudelaire (1821-1867), a champion of modern art, the writer Théophile Gautier (1811-1872), and fellow artists such as Henri Fantin-Latour (1836-1904), who himself was known for his group portraits of artists and writers, and Frédéric Bazille (1841-1870), an early Impressionist whose life was tragically cut short.

The relationship extended beyond social appearances. Manet reportedly borrowed items from Monginot, such as weapons and armor, to use as props in his paintings. This suggests a degree of mutual respect and shared artistic resources. Monginot, while perhaps not as radical in his artistic departures as Manet, was clearly attuned to the shifting artistic winds, and his association with Manet placed him in proximity to the avant-garde discussions taking place in venues like the Café Guerbois, a key meeting spot for artists who would later form the Impressionist group, including Edgar Degas (1834-1917), Claude Monet (1840-1926), and Pierre-Auguste Renoir (1841-1919). While Monginot may not have been a core member of the "Batignolles Group," his ties to Manet ensured he was aware of their artistic explorations.

Monginot also maintained connections with other contemporaries. Records suggest interactions with painters like Antoine Delaume and François Duboy, indicating a broader network within the Parisian artistic community. His life in Paris was complemented by periods spent in Dienville, where he owned property and a studio, often retreating there during the summer months. This pattern of urban engagement and rural respite was common among artists of the period.

Artistic Style: Realism, Still Life, and Thematic Concerns

Charles Monginot was a versatile artist, proficient in several genres including genre painting, portraiture, animal studies, decorative painting, and engraving. However, he gained particular renown for his still life paintings, executed with a strong Realist sensibility. Realism, championed by artists like Gustave Courbet (1819-1877) and Jean-François Millet (1814-1875), emphasized the depiction of everyday subjects and scenes with truthfulness and objectivity, rejecting the idealized and mythological themes favored by the Academy.

Monginot's still lifes often featured meticulously rendered arrangements of food, game, flowers, and tableware. These compositions were characterized by their rich textures, careful attention to detail, and a sophisticated play of light and shadow, often set against dark, atmospheric backgrounds. This approach echoed the tradition of 17th-century Dutch Golden Age still life painters like Willem Kalf or Pieter Claesz, but Monginot infused his work with a 19th-century directness. His ability to capture the tactile qualities of objects – the sheen of silver, the bloom on fruit, the softness of feathers – was highly admired.

While Realism formed the bedrock of his style, Monginot's work, especially in his later career, began to show an awareness of the emerging Impressionist movement. This was evident in his handling of color and light, which could become brighter and more vibrant, and a brushwork that, while still controlled, sometimes displayed a greater freedom than purely academic painting would allow. He skillfully balanced traditional compositional structures with a more modern, painterly approach.

"Still Life" (1869): A Pivotal Work and its Salon Reception

One of Charles Monginot's most discussed works is a painting titled "Still Life," which was exhibited at the Paris Salon of 1869. The Salon, organized by the Académie des Beaux-Arts, was the official, juried art exhibition and the primary venue for artists to gain recognition and patronage. Monginot's "Still Life" from this period is often cited as a masterpiece from his creative peak.

The painting reportedly caused a considerable stir within the Parisian art world. It was described as possessing a "noble classical temperament" combined with "gorgeous and beautiful Impressionist colors." This fusion of qualities was innovative. Monginot was praised for his bold use of color and what some perceived as "rough" or unrefined lines, a departure from the highly polished finish (fini) favored by academic painters. This approach, according to some interpretations, "liberated painting from the shackles of the traditional three-dimensional space," suggesting a move towards a flatter, more decorative picture plane, a concern that was also central to Manet and the burgeoning Impressionist movement.

The reception of "Still Life" was mixed. While it drew sharp criticism from conservative, classical academicians who likely found its technique too audacious and its departure from traditional illusionism unsettling, it received high praise from Édouard Manet. Manet reportedly considered the painting exemplary for its daring color and vigorous handling. This divergence of opinion highlights the artistic tensions of the era, with Monginot's work positioned at a fascinating intersection of established norms and avant-garde exploration. The controversy itself underscored the painting's significance as a work that challenged conventions.

Forays into Singeries and the Decorative Arts

Beyond his easel paintings, Charles Monginot also engaged with decorative arts, including the revival of "Singeries." Singeries, a genre popular in the 18th century with artists like Jean-Baptiste-Siméon Chardin (in his youth) and Christophe Huet, depict monkeys aping human behavior, often in a satirical or whimsical manner. The 19th century saw a renewed interest in this playful and decorative form.

Monginot is mentioned as participating in this revival alongside other artists such as Julien Normant and Edmond de Boislecomte (the latter being a notable specialist in Singeries). This involvement demonstrates Monginot's versatility and his willingness to explore different artistic avenues, including those with a more ornamental or humorous intent. Such decorative work often required a high degree of skill and a light, imaginative touch, qualities that Monginot evidently possessed.

Salon Successes, Recognition, and Collections

Despite the occasional controversy, Charles Monginot achieved considerable recognition during his lifetime. He was a regular participant in the Paris Salons and received official accolades for his work. Notably, he was awarded medals at the Salon in 1864 and again in 1899, indicating sustained critical approval over several decades. His paintings were acquired by prestigious French institutions, a mark of significant contemporary esteem. Works by Monginot can be found in the collections of the Musée du Louvre and the Petit Palais in Paris, as well as the Musée des Beaux-Arts de Tours.

His success was not limited to critical acclaim; he also found a market for his art, partly through collaborations with the fashion industry, suggesting an entrepreneurial aspect to his career. His ability to create appealing and skillfully executed works ensured his popularity with collectors and the public. The consistent quality of his output, particularly in still life, solidified his reputation as a master of the genre.

Later Years, Legacy, and Artistic Evolution

In his later years, Charles Monginot continued to paint, dividing his time between Paris and his property in Dienville. His artistic style, while always rooted in strong observational skills, showed an increasing openness to the brighter palettes and more broken brushwork associated with Impressionism. He never fully abandoned his Realist foundations, but his work demonstrates an intelligent assimilation of contemporary artistic developments.

Monginot's legacy is that of a highly skilled and respected painter who successfully navigated the complex artistic landscape of 19th-century France. He was a master of still life, capable of imbuing everyday objects with a sense of presence and beauty. His close association with Édouard Manet places him within an important circle of artistic innovators, and his own work, particularly pieces like the 1869 "Still Life," contributed to the evolving dialogue about the nature and direction of modern painting.

He may not have been a revolutionary figure on the scale of Manet or Monet, but he was a significant artist who absorbed and synthesized various influences, creating a body of work that is both technically accomplished and historically interesting. He represents a cohort of artists who, while perhaps not at the vanguard of radical change, played a crucial role in the broader shift from academicism towards modernism. His influence can be seen in the way he combined meticulous Realist detail with a more painterly and color-conscious approach, anticipating some of the concerns that would preoccupy later artists.

Charles Monginot in the Art Market

The works of Charles Monginot continue to appear on the art market, and their reception provides insight into his enduring appeal. His paintings, particularly his still lifes, are sought after by collectors of 19th-century French art. The aforementioned "Still Life," a key work, was notably collected by the MAJEI (Matis Art Education International) Art Fund and has been featured at auction, drawing attention from art connoisseurs and institutions.

Specific auction records provide tangible evidence of his market presence. For instance, a drawing by Monginot titled "Homme debout accroupé" (Standing Crouching Man) reportedly sold for 400 Euros. Another drawing, depicting flowers and a peacock, achieved a price of 34.99 Euros. While these prices for drawings might seem modest compared to major oil paintings by leading Impressionists, they indicate a consistent level of interest. His oil paintings, especially significant still lifes, would command considerably higher prices, reflecting their quality and historical importance.

The market evaluation of Monginot's work acknowledges his skill, his connection to important artistic movements, and the aesthetic appeal of his paintings. He is recognized as a significant practitioner of Realist still life with Impressionistic leanings, a combination that holds appeal for those interested in the nuanced transitions of 19th-century art.

Conclusion: Monginot's Enduring Place in 19th-Century French Art

Charles Monginot stands as a fascinating figure in the rich tapestry of 19th-century French art. His career, spanning from the mid-century dominance of academic Realism to the rise and establishment of Impressionism, reflects the dynamic artistic currents of his time. As a student of Thomas Couture, he received a solid grounding in traditional techniques, which he then adapted and evolved through his own observations and his interactions with progressive artists like Édouard Manet.

His mastery of still life painting is undeniable, with works that combine meticulous detail, rich textures, and a sophisticated understanding of light and color. The controversy surrounding his 1869 "Still Life" underscores his willingness to push boundaries, even if he did not fully embrace the radicalism of some of his contemporaries. His inclusion in Manet's "Music in the Tuileries Gardens" and their documented friendship highlight his integration into the Parisian avant-garde circles.

While he may not be as widely known today as figures like Monet, Degas, Renoir, or even his friend Manet, Charles Monginot's contribution is significant. He was an artist admired by his peers, recognized by the Salon, and collected by major institutions. His work offers a valuable perspective on the period, demonstrating how an artist could remain true to principles of careful observation and craftsmanship while also engaging with the innovative spirit of modernism. His paintings continue to be appreciated for their beauty, technical skill, and their embodiment of a pivotal moment in art history, securing his place as a distinguished and noteworthy French painter of his era.