Ferdinand Hodler stands as one of Switzerland's most celebrated artists, a pivotal figure whose work bridged the late 19th and early 20th centuries. Born in Bern in 1853 and passing away in Geneva in 1918, Hodler carved a unique path through the shifting artistic landscapes of Realism, Symbolism, and the burgeoning Modernist movements. He is renowned not only for his powerful imagery, often depicting scenes from Swiss history, landscapes, and profound human experiences, but also for his distinctive artistic theory known as "Parallelism." His life, marked by early hardship and later international acclaim, profoundly shaped an oeuvre characterized by formal rigor, emotional depth, and a persistent search for universal truths.

Early Life and Formative Tragedies

Ferdinand Hodler's journey began in humble circumstances in Bern on March 14, 1853. His father, Jean Hodler, was a carpenter, and his mother, Marguerite Neukomm, came from a peasant family. Poverty was a constant companion in his early years, but personal tragedy soon cast an even longer shadow. By the age of eight, Hodler had already lost his father and two younger brothers. His mother remarried, but she too succumbed to tuberculosis, a disease that would tragically claim all his remaining siblings over the years.

This profound and repeated exposure to death and loss at a formative age left an indelible mark on Hodler's psyche and, consequently, his art. Themes of mortality, fate, human suffering, and the stoic endurance of life became recurring motifs throughout his career. The stark reality of human fragility was not an abstract concept for Hodler; it was a lived experience that infused his work with a palpable sense of gravity and introspection. Despite these immense hardships, his artistic inclinations found an outlet.

Artistic Training and Early Career

Recognizing his talent, Hodler's stepfather apprenticed him to a local painter specializing in tourist views of the Alps. This early training provided him with foundational skills in landscape painting. In 1868, seeking more formal instruction, he entered a decorative arts school in Thun. However, his ambition drove him further, and in 1871, at the age of 18, he made the pivotal decision to move to Geneva. There, he sought out the tutelage of Barthélemy Menn.

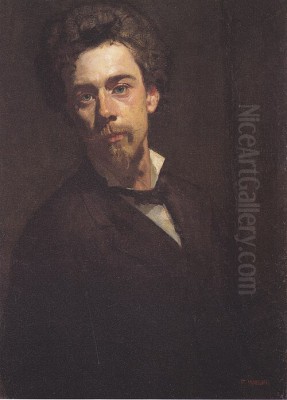

Menn was a crucial figure in Hodler's development. A former pupil of the great Neoclassical master Jean-Auguste-Dominique Ingres, Menn instilled in Hodler a deep respect for drawing, composition, and clarity of form. While Menn himself was open to newer trends like the atmospheric landscapes of Camille Corot, his emphasis on structure provided Hodler with a solid technical grounding. During these early years in Geneva, Hodler initially worked within a Realist framework, influenced by artists like Gustave Courbet, painting portraits, landscapes, and genre scenes that reflected the world around him with sober accuracy. Works from this period demonstrate his developing skill and keen observational powers.

The Emergence of Symbolism and Parallelism

By the 1880s, Hodler began to move beyond straightforward Realism. Like many artists across Europe, he felt the pull of Symbolism, a movement that sought to express deeper meanings, ideas, and emotions rather than simply depicting external reality. Artists such as Gustave Moreau and Odilon Redon in France were exploring mythological and dreamlike subjects, while in Belgium, Fernand Khnopff delved into enigmatic psychological states. Hodler's engagement with Symbolism was distinctly his own, deeply rooted in his personal experiences and philosophical reflections.

This period saw the development of his most significant contribution to art theory: "Parallelism" (Parallelismus). Hodler conceived of Parallelism as a principle reflecting the inherent order and unity he perceived in nature and humanity. He observed that nature often organizes itself through repetition and symmetry – rows of trees, waves on a lake, the structure of crystals, the bilateral symmetry of the human body. He sought to translate this natural harmony into his art through the rhythmic arrangement of forms, lines, and colors.

Parallelism, in practice, involved the symmetrical or repetitive arrangement of figures and compositional elements. Figures often appear in frieze-like processions or static, symmetrical groupings, their gestures echoed or mirrored. Landscapes were structured with strong horizontal or vertical lines, emphasizing underlying geometric patterns. This approach aimed to create a sense of monumentality, timelessness, and universal significance, lifting the subject matter beyond the specific and anecdotal into the realm of the symbolic and the essential. It was a quest for visual order that mirrored a deeper search for meaning in a world often perceived as chaotic.

Masterworks: Exploring Life, Death, and Nature

Hodler's mature style, integrating Symbolism and Parallelism, found powerful expression in several key works that cemented his reputation. The Night (Die Nacht), completed around 1889-1890, is arguably his breakthrough painting. It depicts several sleeping figures, including a self-portrait of Hodler himself, startled awake by the looming, black-shrouded figure of Death. The figures are arranged in a rhythmic, parallel structure across the canvas. The painting's stark confrontation with mortality, its dreamlike atmosphere, and its bold composition caused a scandal when it was rejected from the official Beaux-Arts exhibition in Geneva due to its perceived morbidity and nudity. Hodler defiantly exhibited it privately, where it garnered significant attention and critical debate, ultimately launching his international career.

Another major work, Day (Der Tag), created around 1900, serves as a thematic counterpoint to The Night. Here, five nude women are depicted awakening to the dawn, their arms raised in gestures of welcome or prayer. The composition is again based on Parallelism, with the figures forming a symmetrical, harmonious group against a simplified landscape background. The work symbolizes life, rebirth, and spiritual awakening, embodying a sense of cosmic harmony and optimism that contrasts with the somber tones of The Night.

Hodler also applied his principles to depictions of human labor and Swiss identity. The Woodcutter (Der Holzfäller), painted around 1910, shows a powerful male figure, axe raised mid-swing against a backdrop of ordered trees. The figure embodies strength, vitality, and a connection to the Swiss landscape. The repetitive vertical lines of the trees and the dynamic, yet controlled, pose of the woodcutter exemplify Parallelism. This work became so iconic that it was later featured on the Swiss 50 Franc banknote, solidifying Hodler's status as a national painter. These works, among others, showcase Hodler's ability to tackle profound themes – life, death, work, spirituality, the human condition – through his unique and highly structured visual language.

Landscapes: The Soul of Switzerland

While Hodler gained fame for his large-scale figurative compositions, his landscape paintings represent a significant and equally innovative part of his oeuvre. He possessed a deep connection to the Swiss environment, particularly the majestic Alps and the serene beauty of its lakes, such as Lake Geneva and Lake Thun. His landscapes moved beyond mere topographical representation, seeking instead to capture the essential structure, grandeur, and spiritual resonance of nature.

Applying the principles of Parallelism, Hodler often simplified mountain ranges and shorelines into bold, rhythmic forms and strong horizontal bands. He emphasized the underlying geometry of the landscape, revealing the inherent order he perceived. His depictions of mountains like the Dents du Midi or the Stockhorn chain are not just views but powerful symbols of permanence and natural majesty. He was fascinated by the effects of light and atmosphere, often painting the same view repeatedly at different times of day or under varying weather conditions, exploring subtle shifts in color and mood.

Unlike the Impressionists, such as Claude Monet, who sought to capture fleeting moments of light and perception, Hodler aimed for a more timeless and structured vision of nature. His approach might be seen as closer in spirit, though different in execution, to Paul Cézanne's attempts to find the geometric underpinnings of the natural world. Hodler's landscapes often possess a profound stillness and a mystical quality, suggesting a deep spiritual connection between humanity and the cosmos, as reflected in the ordered beauty of the Swiss terrain. His contemporary, Giovanni Segantini, also painted the Alps with symbolic weight, but Hodler's structural rigor remained distinct.

Portraiture and the Human Figure

Hodler was also a penetrating portraitist. His portraits, like his other works, evolved from an early Realism towards a more stylized and psychologically insightful approach. He painted numerous self-portraits throughout his career, chronicling his own aging process and inner states with unflinching honesty. These works often convey a sense of stoic introspection and intense concentration, reflecting the seriousness with which he approached his art and life.

His portraits of others often focused on capturing the essential character and inner life of the sitter, sometimes using simplified forms and expressive lines that bordered on Expressionism. He painted commissioned portraits but was perhaps most compelling when depicting those close to him. His relationships with women were complex and often tumultuous, and these dynamics found their way into his art. He had a son, Hector, with Augustine Dupin. He later married Bertha Stucki in 1889 (divorced 1891) and then Berthe Jacques in 1898.

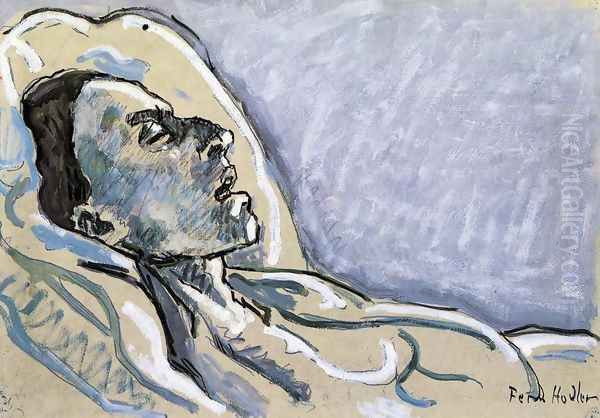

One of the most moving and harrowing series of works in Hodler's entire output documents the illness and death of his mistress, Valentine Godé-Darel, between 1914 and 1915. Hodler recorded her decline from cancer in numerous paintings and drawings, capturing her physical suffering and changing appearance with raw, unsentimental honesty. These works are a profound meditation on love, loss, and the confrontation with mortality that had haunted Hodler since his youth. They stand as a testament to his commitment to depicting life's fundamental truths, however painful, and can be compared in their emotional intensity to the self-examinations of Vincent van Gogh or the raw figuration of Egon Schiele.

International Recognition and Influence

Following the success and notoriety of The Night, Hodler's reputation grew steadily, both within Switzerland and internationally. He exhibited frequently in Paris, Munich, and Berlin, and became associated with major avant-garde movements and groups. In 1900, his work was prominently featured at the Paris Universal Exposition, earning him widespread acclaim. He was particularly celebrated by the Secession movements in Vienna and Berlin, which sought to break away from academic conservatism.

In Vienna, his work resonated with the Symbolist and decorative tendencies of artists like Gustav Klimt, and he exhibited with the Vienna Secession, whose building was designed by Joseph Maria Olbrich. In Germany, particularly Berlin, Hodler achieved significant success and was seen as a leading figure of Modernism. He exhibited with the Berlin Secession, alongside prominent German artists such as Max Liebermann, Lovis Corinth, and Max Slevogt. His emphasis on line, simplified form, and emotional expression found kinship with the emerging Expressionist movement, influencing younger artists.

Hodler's unique style, particularly Parallelism, offered a distinct alternative to French Impressionism and Post-Impressionism. His emphasis on structure, symbolism, and monumental composition aligned him with other significant figures seeking new directions in art, such as the Norwegian Edvard Munch, whose work also explored profound psychological themes, or the French painter Puvis de Chavannes, known for his large-scale allegorical murals. Hodler's international connections and exhibitions ensured his place within the broader narrative of European modern art.

Personal Life: Turmoil and Art

Hodler's personal life remained complex throughout his years of growing fame. His relationships were often intense and marked by change. His first marriage to Bertha Stucki ended in divorce after only two years. His relationship with Augustine Dupin, the mother of his son Hector (who would later become a key figure in the Esperanto movement), occurred before this marriage. His second marriage, to Berthe Jacques in 1898, also eventually dissolved.

His longest and perhaps most significant later relationship was with Valentine Godé-Darel, whom he met around 1908. Their bond was deep, and her death in 1915 affected him profoundly, as evidenced by the powerful series of works documenting her final months. These personal experiences – love, fatherhood, partnership, illness, and loss – undoubtedly fueled the emotional intensity found in his art. The recurring themes of human connection, suffering, and resilience in his work were not merely abstract concerns but were deeply intertwined with the fabric of his own lived reality.

Controversies and Challenges

Despite his growing success, Hodler's work often courted controversy. His bold style and sometimes challenging subject matter did not always align with conservative tastes. The rejection of The Night in Geneva in 1891 was just one early example. In 1896, a major commission for monumental frescoes depicting Swiss history for the Swiss National Museum (Landesmuseum) in Zurich led to fierce public debate over his stylized, non-naturalistic approach. Although he eventually completed the frescoes, the controversy highlighted the resistance his innovative style could provoke.

Similarly, some of his submissions to the Geneva National Exhibition in 1896 were met with demands for modification, leading to disputes. Even his successes abroad were sometimes met with critical reservations. At the Berlin Secession exhibition in 1900, while generally well-received, some critics found his compositions too rigid or his symbolism obscure. These challenges underscore Hodler's position as an innovator pushing against established norms. His unwavering commitment to his artistic vision, even in the face of criticism, was characteristic of his determined personality.

Late Works and Final Years

In his later years, Hodler continued to work prolifically, particularly focusing on landscapes. His late style often showed an increased simplification of form and a heightened sensitivity to color and light. He produced numerous series of paintings depicting Lake Geneva and the surrounding mountains, capturing the changing atmosphere with broad, expressive brushstrokes and harmonious color palettes. These works sometimes verge on abstraction, with compositions reduced to essential horizontal bands of water, land, and sky.

This serial approach, exploring variations on a single motif, can be compared to Claude Monet's late series of Water Lilies, although Hodler's focus remained more on structural permanence than on fleeting effects. His late landscapes possess a serene, almost meditative quality, suggesting a final, peaceful communion with the natural world that had always been central to his art.

However, his final years were also marked by declining health and personal loss. The death of Valentine Godé-Darel in 1915 was a severe blow. In 1914, Hodler had signed a petition condemning the German bombardment of Reims Cathedral during World War I, an act which led to his expulsion from German art associations and damaged his standing in Germany, where he had previously enjoyed great success. Suffering from pulmonary edema, Hodler passed away in Geneva on May 19, 1918, leaving behind a vast and powerful body of work. He reportedly died while working on a final view of Lake Geneva from his window.

Legacy and Re-evaluation

Ferdinand Hodler is widely regarded as Switzerland's most important painter of the modern era and a key figure in European Symbolism. His development of Parallelism remains a unique contribution to art theory and practice, demonstrating a powerful synthesis of observation, philosophical thought, and formal innovation. His work successfully blended monumental composition with intense emotional expression, and realism with symbolic depth.

While internationally acclaimed during his lifetime, Hodler's reputation experienced a decline in the decades immediately following his death, overshadowed by newer avant-garde movements like Cubism and Surrealism. However, from the late 20th century onwards, there has been a significant resurgence of interest in his work. Major retrospectives, such as those held for the centenary of his death in 2018 in Geneva and Bern, have reaffirmed his importance. Exhibitions like "Ferdinand Hodler and Modernist Berlin" (2017) and "Apropos Hodler" (2023), which invited contemporary artists to engage with his legacy, demonstrate his continuing relevance.

His paintings are now housed in major museums worldwide, with particularly strong collections in Switzerland at the Kunsthaus Zürich, the Kunstmuseum Bern, and the Musée d'Art et d'Histoire in Geneva. Hodler's influence can be seen in the development of Expressionism and in subsequent artists who sought to combine formal structure with emotional or spiritual content. He remains a potent symbol of Swiss national identity, yet his exploration of universal human themes—life, death, love, suffering, and the search for order—transcends national boundaries.

Conclusion

Ferdinand Hodler's life and art were forged in the crucible of personal tragedy and artistic ambition. From his early Realist works to his mature Symbolist compositions governed by Parallelism, he pursued a singular vision with unwavering determination. He sought order and harmony in a world marked by loss, finding it in the rhythms of nature and the structure of human form. His powerful depictions of the Swiss landscape, historical events, and the fundamental experiences of human existence continue to resonate with viewers today. As a bridge between 19th-century traditions and 20th-century Modernism, Hodler carved out a unique and enduring place in the history of art, leaving behind a legacy of profound emotional depth and striking formal innovation.