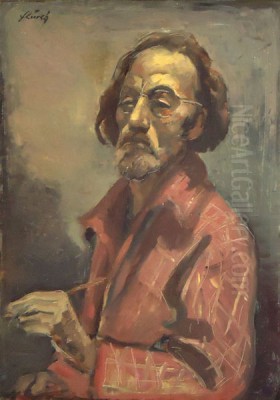

Johann Robert Schuerch stands as a fascinating, albeit somewhat enigmatic, figure in early 20th-century European art. Active during a period of immense social upheaval and artistic experimentation, Schuerch carved out a unique niche with his often dark, deeply personal, and unflinchingly honest depictions of life's fringes. His work, characterized by a raw expressiveness and a focus on themes of despair, isolation, and mortality, offers a compelling window into the anxieties of his time. Though perhaps not as widely celebrated as some of his contemporaries, recent exhibitions have brought renewed attention to his powerful and distinctive artistic voice.

A Life Briefly Illuminated

Specific details about Johann Robert Schuerch's personal life remain relatively scarce, adding to the mystique surrounding his art. However, key dates frame his existence: he was born in 1895 and passed away in 1941. This places his life and primary artistic output squarely within the tumultuous first half of the 20th century, a period encompassing World War I, the societal shifts of the interwar years, and the rise of ideologies that would lead to World War II. This backdrop of conflict and uncertainty undoubtedly permeated the cultural atmosphere in which he worked. His Swiss origins are suggested by later exhibitions of his work in Switzerland, grounding him within a specific national context, yet his themes possess a universal resonance.

The lack of extensive biographical records means his art must often speak for itself. We glean insights into his worldview and preoccupations not through detailed historical accounts of his experiences, but through the recurring motifs, stylistic choices, and emotional tenor of his paintings and drawings. His focus seems directed inward, exploring psychological states, and outward, observing the often-overlooked or uncomfortable aspects of human existence.

The Artistic Vision: Style and Themes

Schuerch's art is immediately recognizable for its pessimistic and dramatic tone. He did not shy away from difficult subjects; indeed, he seemed drawn to them. His canvases and drawings frequently explore the lives of those on the margins of society, individuals grappling with poverty, alienation, and hardship. This focus aligns him with a tradition of social realism, yet his approach transcends mere documentation. There is a profound psychological depth to his work, an exploration of the inner lives of his subjects, often imbued with a palpable sense of loneliness and despair.

Death is another recurring and central theme in Schuerch's oeuvre. Not merely as a biological fact, but as an existential presence, a specter haunting the living. This preoccupation with mortality connects him to a long lineage of artists, from the medieval creators of danse macabre imagery to later figures like the Symbolists. His treatment of the subject is often direct, sometimes allegorical, but always imbued with a sense of gravity and introspection.

Stylistically, Schuerch employed a technique that matched the intensity of his themes. His brushwork is often described as rough and highly expressive, prioritizing emotional impact over polished naturalism. This links him to the broader currents of Expressionism that swept through Europe, particularly in German-speaking countries. Artists like Ernst Ludwig Kirchner or Erich Heckel, associated with the Die Brücke group, similarly used distorted forms and bold, non-naturalistic color to convey intense feelings. Schuerch's work, however, is often placed within the context of "New Realism," likely referring to the Neue Sachlichkeit (New Objectivity) movement that emerged in Germany in the 1920s as a reaction against Expressionism's perceived excesses.

Echoes of Expressionism and Realism

While sometimes associated with New Realism, Schuerch's style retains a strong expressive quality that prevents easy categorization. The New Objectivity movement, featuring artists like George Grosz and Otto Dix, often employed a cooler, more detached, and bitingly satirical approach to depicting the perceived corruption and decay of Weimar society. Schuerch shares with Grosz a critical eye towards societal failings and a willingness to depict uncomfortable truths, and perhaps shares with Dix a focus on the harsh realities of life and the physical and psychological scars left by war and hardship.

However, Schuerch's intense focus on personal despair and existential angst also resonates with artists beyond the immediate Neue Sachlichkeit circle. The profound loneliness in his work echoes the existential dread found in the paintings of Edvard Munch, the Norwegian pioneer whose work explored themes of anxiety, love, and death with searing psychological intensity. Similarly, the focus on suffering and the downtrodden brings to mind the powerful prints and drawings of Käthe Kollwitz, a German artist who dedicated her career to depicting the plight of the poor and the devastating impact of war.

Furthermore, Schuerch's exploration of the absurd and the grotesque finds parallels in the work of artists like James Ensor, the Belgian painter known for his haunting images of masks, skeletons, and carnivalesque scenes, often blending satire with a deep sense of unease. The comparison to Ensor highlights Schuerch's interest in the theatricality of life and death, and the masks people wear, literally or figuratively. The darker, more fantastical elements sometimes present in Schuerch's work might even evoke the nightmarish visions of an artist like Alfred Kubin, the Austrian printmaker and illustrator associated with Symbolism and early Expressionism.

Schuerch's unique blend of expressive technique and realist observation, filtered through a deeply pessimistic lens, sets him apart. He navigated the artistic landscape between the raw emotion of Expressionism and the cynical observation of New Objectivity, creating a body of work that feels both historically situated and personally distinct. His art avoids easy sentimentality, confronting viewers with stark portrayals of human vulnerability.

Representative Works: "Faces and Days of Paradise"

Among Schuerch's notable creations is the series known as "Gesichter und Tage des Paradieses," which translates to "Faces and Days of Paradise." While specific images from this series require further investigation to describe in detail, the title itself, juxtaposed with Schuerch's known thematic concerns, is provocative. It suggests an ironic or perhaps deeply melancholic exploration of what constitutes "paradise" in a world marked by suffering and marginalization.

This series likely encapsulates many of his core artistic preoccupations. The "Faces" might refer to his penetrating portraits of individuals, perhaps capturing their inner turmoil, resilience, or resignation. The "Days of Paradise" could ironically depict scenes of everyday life among the marginalized, finding moments of fleeting connection or beauty amidst hardship, or it could be a more direct, perhaps bitter, commentary on unattainable ideals. It is within works like these that Schuerch's unique handling of image and form, his ability to convey profound emotion through expressive means, and his unwavering focus on the solitary figure would be most evident. This series stands as a testament to his sustained engagement with the human condition in its less comfortable aspects.

Rediscovery and Legacy

Despite the power and individuality of his work, Johann Robert Schuerch remained relatively obscure for many years following his death in 1941. However, the art world has a way of rediscovering compelling voices from the past. In recent years, Schuerch's work has experienced a resurgence of interest, suggesting a growing appreciation for his unique contribution to 20th-century art.

A significant event marking this rediscovery was the exhibition of his work collection titled "Vision (1913-1941)" at the Bündner Kunsthalle Chur in Switzerland, which opened in January 2020. Curated by Damian Jurek, this exhibition provided a crucial platform for re-evaluating Schuerch's output, spanning nearly three decades of his creative life. Such retrospectives are vital for artists who may have been overshadowed by contemporaries like Max Beckmann, whose complex allegories also navigated the turbulent German scene, or even prominent Swiss artists working in different veins, such as the Symbolist Ferdinand Hodler or the Nabis-influenced Félix Vallotton.

Furthermore, the mention of a recent exhibition by Galerie Müller indicates ongoing commercial and critical interest. Galleries play a crucial role in bringing an artist's work back into public consciousness and facilitating new scholarship. These efforts suggest that Schuerch's art continues to resonate with contemporary audiences, perhaps because his themes of alienation, social critique, and existential questioning remain relevant today.

Johann Robert Schuerch's legacy lies in his unflinching portrayal of the human condition, particularly its darker facets. His expressive, often unsettling images serve as a powerful reminder of the anxieties and struggles that marked his era, viewed through a distinctly personal and empathetic lens. While details of his life may be sparse, his art provides a rich, challenging, and ultimately rewarding field of study, securing his place as a significant, if previously underappreciated, voice from the margins of modern art history. His work invites contemplation on the nature of despair, the meaning found in adversity, and the enduring power of the human spirit even when faced with the abyss.