Egon Schiele stands as one of the towering, albeit controversial, figures of early 20th-century art. A protégé of Gustav Klimt and a central force in Austrian Expressionism, Schiele's brief but incandescent career produced a body of work renowned for its raw intensity, psychological depth, and unflinching exploration of the human form and psyche. In less than a decade of mature artistic output, he forged a unique visual language characterized by distorted figures, jagged lines, and unsettling emotional honesty, leaving an indelible mark on the trajectory of modern art. His life, marked by both artistic triumph and personal scandal, unfolded against the backdrop of Vienna's vibrant yet decaying cultural milieu at the twilight of the Austro-Hungarian Empire, a context crucial to understanding his provocative and enduring art.

Early Life and Artistic Awakening

Egon Schiele was born on June 12, 1890, in Tulln an der Donau, a small town near Vienna, Austria. His father, Adolf Schiele, was a station master for the Austrian State Railways, and his mother, Marie Soukupová Schiele, hailed from Krumau (now Český Krumlov) in Bohemia, possessing Czech and German heritage. From a young age, Schiele displayed a precocious talent for drawing, often sketching trains and the world around him. His childhood, however, was overshadowed by the declining mental health and eventual death of his father from syphilis in 1905, an event that profoundly impacted the young artist and likely fueled the themes of mortality and psychological distress present in his later work.

Despite his evident artistic gifts, Schiele found traditional schooling stifling. His uncle and guardian, Leopold Czihaczek, initially hoped he would follow a conventional path but eventually recognized his nephew's artistic vocation. In 1906, at the age of sixteen, Schiele enrolled at the prestigious Vienna Academy of Fine Arts (Akademie der Bildenden Künste Wien). He studied under the conservative painter Christian Griepenkerl, a traditionalist whose rigid academic methods quickly frustrated the young, burgeoning modernist. Schiele found the academy's emphasis on classical techniques and historical subjects utterly incompatible with his desire for personal expression and exploration of contemporary life.

His dissatisfaction grew, leading him and several like-minded students to form the Neukunstgruppe (New Art Group) in 1909. This act of rebellion signaled his definitive break from the academy's constraints. He left the institution that same year, determined to pursue his own artistic vision, one already beginning to absorb the radical new ideas circulating in Vienna's avant-garde circles. This period marked the beginning of his search for a truly authentic and modern form of expression, moving away from academicism towards a style that could convey the anxieties and complexities of the modern soul.

The Influence of Klimt and the Vienna Secession

A pivotal moment in Schiele's early career was his encounter with Gustav Klimt in 1907. Klimt, already the established leader of the Vienna Secession movement and Austria's most celebrated artist, recognized Schiele's extraordinary talent. He became a mentor figure, offering encouragement, introducing Schiele to patrons, exchanging drawings, and even helping him secure commissions. Klimt's influence is palpable in Schiele's early works, particularly in the decorative patterning, flattened perspectives, and elegant linearity reminiscent of Klimt's own Jugendstil (Art Nouveau) style. Works from this period sometimes echo Klimt's use of gold leaf and ornamental surfaces.

The Vienna Secession, founded in 1897 by Klimt, Koloman Moser, Josef Hoffmann, Joseph Maria Olbrich, and others, was a crucial incubator for modern art in Austria. Its members sought to break away from the historicism dominating the official art establishment (represented by the Vienna Künstlerhaus). They championed artistic freedom, the integration of art and life (Gesamtkunstwerk), and exposure to international avant-garde movements like French Impressionism and Symbolism. The Secession building itself, designed by Olbrich, became a landmark exhibition space for modern art.

Schiele absorbed the Secession's spirit of rebellion and its emphasis on subjective experience. He admired Klimt's decorative elegance and symbolic depth. However, Schiele quickly moved beyond mere imitation. While Klimt's art often veiled sensuality in opulent decoration and mythic allegory, Schiele stripped away the ornamentation. He took the expressive potential of line, a key element for Klimt and the Secessionists, and pushed it towards a raw, nervous, and psychologically charged energy. Where Klimt's lines were often sinuous and graceful, Schiele's became angular, broken, and tense, reflecting inner turmoil rather than aesthetic harmony. He embraced the Secession's focus on the psychological, but delved into darker, more explicit territories of anxiety, desire, and mortality.

Forging a Unique Expressionist Style

By 1910, Schiele had decisively forged his own path, becoming a leading figure of Austrian Expressionism alongside Oskar Kokoschka. Expressionism, a broader European movement flourishing particularly in Germany (with groups like Die Brücke, including Ernst Ludwig Kirchner and Erich Heckel) and Austria, prioritized subjective experience and emotional expression over objective reality. Artists like Edvard Munch in Norway had already paved the way with psychologically intense works exploring themes of alienation, fear, and desire. Schiele's contribution was a particularly raw and confrontational style focused on the human figure.

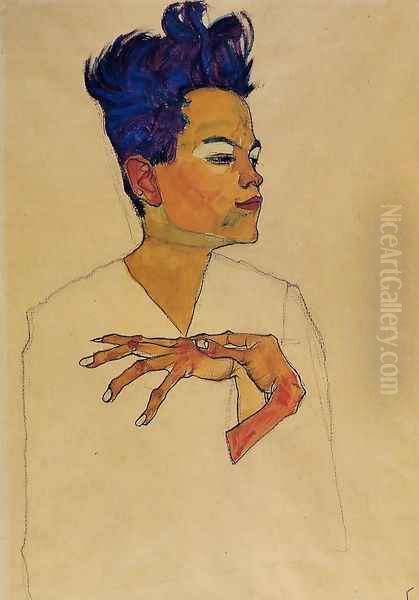

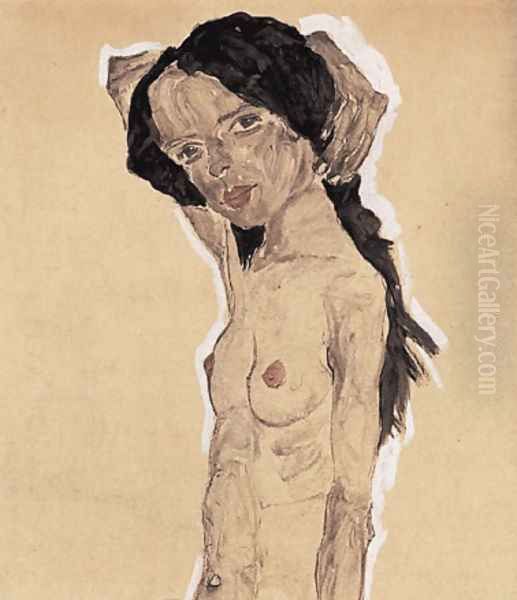

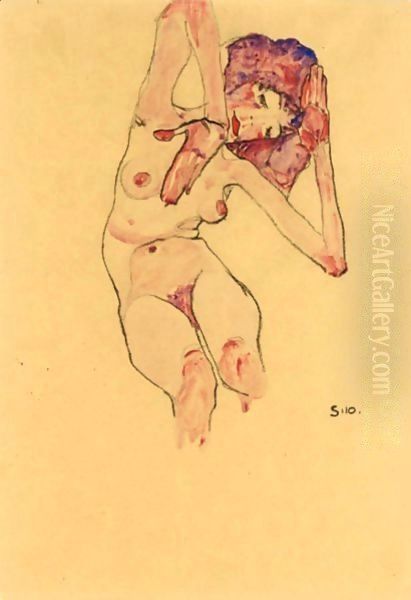

His signature style is defined by several key characteristics. Firstly, the masterful and radical use of line: sharp, jagged, and seemingly agitated, his lines carve out figures with brutal honesty, often distorting anatomy to heighten emotional impact. These lines convey a sense of nervous energy, vulnerability, and psychological tension. Secondly, his depiction of the human body: Schiele's nudes and portraits are rarely idealized. Figures are often emaciated, contorted into awkward, angular poses, their bodies appearing fragile, exposed, and psychologically raw. He explored themes of sexuality, puberty, suffering, and death with an unprecedented explicitness.

Thirdly, his use of color and composition: Schiele employed color not for naturalistic representation but for emotional effect, often using stark contrasts, sickly greens, bruised purples, and feverish reds against stark white backgrounds. His compositions frequently isolate figures in empty space, emphasizing their loneliness and vulnerability, or cram them into claustrophobic frames. The perspective is often flattened, contributing to the unsettling, confrontational quality of the images. Fourthly, the prevalence of self-portraits: Schiele produced over a hundred self-portraits, using his own face and body as a primary vehicle for exploring identity, anxiety, narcissism, and the artist's role. These works show him in various guises – defiant, suffering, questioning, provocative.

His work often courted controversy due to its explicit sexual content and unflinching portrayal of the human condition, challenging the conservative morals of Viennese society. Yet, it was precisely this raw honesty and psychological penetration that established him as a major force in modern art, distinct even from his mentor Klimt and contemporary Kokoschka.

Major Works and Thematic Concerns

Schiele's oeuvre, though produced over a short period, is rich with iconic works that encapsulate his style and thematic preoccupations. His self-portraits are among his most compelling creations. Self-Portrait with Chinese Lantern Plant (1912) is a prime example, showing the artist gaunt, wide-eyed, with fingers splayed in a tense, almost claw-like gesture, the wilting plant perhaps symbolizing fragility or decay. The distorted perspective and intense gaze confront the viewer directly, conveying a sense of inner turmoil and defiance. Earlier self-portraits, like the Self-Portrait of 1906, show the influence of academic training but already hint at the psychological intensity to come.

His depictions of the human body, particularly nudes, are central to his work. Standing Nude Girl (1910) or Seated Female Nude (1913) exemplify his approach: figures are rendered with stark lines, often emaciated or awkwardly posed, emphasizing vulnerability and a raw physicality devoid of traditional eroticism. These works explore the body as a site of both desire and suffering. Death and the Maiden (1915), painted after his relationship with Wally Neuzil ended and during wartime, is a powerful allegorical work. It depicts a skeletal figure of Death embracing a young woman, a theme revisited from Renaissance art but imbued with Schiele's characteristic Expressionist angst and a palpable sense of loss and impending doom.

The Portrait of Wally Neuzil (1912) is one of his most famous portraits, capturing the intensity and complexity of his relationship with his model and lover. Her direct gaze and slightly tilted head convey both strength and vulnerability. This painting later became the subject of a major art restitution case. Other significant works include portraits of patrons like Arthur Roessler, family members like his sister Gerti Schiele (1909), and explorations of relationships, such as The Lovers (1917), which depicts him and his wife Edith with a newfound, albeit still somewhat tense, tenderness compared to earlier works. His cityscapes and landscapes, like Decaying Mill (painted during WWI) or The Artist's Room in Neulengbach (1911), also carry his signature style, often imbuing inanimate scenes with psychological weight and a sense of unease or melancholy.

Controversy and Legal Troubles

Schiele's art and life were frequently entangled with controversy and legal issues, stemming largely from the explicit nature of his work and his unconventional lifestyle. The most significant incident occurred in 1912 when Schiele, then living in the town of Neulengbach with his model and partner Wally Neuzil, was arrested. The initial charges were serious, including the alleged seduction and abduction of an underage girl who had run away from home. While these grave accusations were ultimately dropped, the authorities searched his studio and confiscated over one hundred drawings deemed pornographic.

He was subsequently charged with exhibiting erotic drawings in a place accessible to children. During the trial, in a dramatic gesture, the presiding judge burned one of the confiscated drawings over a candle flame in the courtroom, condemning it as offensive. Schiele was found guilty of the lesser charge and sentenced to 24 days in prison. He had already spent 21 days in custody awaiting trial, so he served an additional three days.

This experience deeply affected Schiele. While imprisoned, he created a series of poignant drawings and watercolors documenting his confinement, capturing the bleakness of his cell and his own feelings of persecution and despair. The titles themselves, such as Hindering the Artist is a Crime, It is Murdering Life Itself!, reveal his sense of outrage. The Neulengbach affair solidified his reputation as an enfant terrible but also arguably led to a slight tempering of the explicitness in some of his subsequent work, though his focus on the human body and psychological intensity remained unwavering.

Decades after his death, Schiele's work became embroiled in legal battles concerning Nazi-looted art. The most famous case involved the Portrait of Wally Neuzil. Loaned by the Leopold Museum in Vienna to the Museum of Modern Art (MoMA) in New York for a 1997 exhibition, the painting was subpoenaed by the New York County District Attorney based on claims by the heirs of Lea Bondi Jaray, a Jewish gallery owner from whom the work was allegedly confiscated by a Nazi agent. After years of complex legal proceedings, the case was settled in 2010, with the Leopold Museum paying $19 million to the heirs and acknowledging the painting's troubled provenance, allowing the work to return to Vienna. Another case involved the heirs of Fritz Grünbaum, a Jewish cabaret artist and collector whose art collection, including works by Schiele, was looted by the Nazis. These restitution cases highlight the dark legacy of the Nazi era and the ongoing efforts to achieve justice for victims of looting, with Schiele's valuable works often at the center of these disputes.

Personal Life and Relationships

Schiele's personal life was as intense and complex as his art, deeply intertwined with his creative process. His relationships, particularly with women, were central to both his life and his work, often serving as direct inspiration. His personality was described by contemporaries as shy, sensitive, intense, and somewhat narcissistic, making social interactions sometimes difficult but also fueling his introspective art.

His most significant early relationship was with Valerie Neuzil, known as Wally. They met around 1911, possibly introduced by Klimt, and she quickly became his primary model and companion. Wally features in many of his most iconic works from 1911 to 1915, including the famous Portrait of Wally and the harrowing Death and the Maiden. Their relationship was passionate but unconventional, defying bourgeois norms. They lived together in Krumau (his mother's hometown) and later Neulengbach, but their presence often provoked suspicion and hostility from conservative locals, contributing to the circumstances leading to his 1912 arrest.

In 1914, Schiele met Edith Harms and her sister Adele, who lived across the street from his Vienna studio and came from a respectable middle-class background. Seeking social stability and perhaps desiring a more conventional family life, Schiele decided to marry Edith. In a letter, he rather callously proposed to Wally that she remain his mistress while he married Edith, an arrangement Wally understandably refused. Their painful separation is believed to be the subject of Death and the Maiden. Schiele married Edith Harms in June 1915, shortly before being conscripted into the army.

His marriage to Edith brought a degree of domesticity previously absent from his life. His later portraits of Edith, and works like The Family (an unfinished painting depicting himself, Edith, and an infant), suggest a move towards themes of intimacy and domestic life, although still rendered with his characteristic emotional intensity and stylistic angularity. Despite this newfound stability, his fundamental artistic concerns with the human condition, mortality, and psychological depth persisted. His relationships, fraught with passion, conflict, and loss, provided fertile ground for his exploration of human vulnerability and connection.

The Impact of World War I

The outbreak of World War I in August 1914 cast a long shadow over Europe, and its impact was felt deeply in the Austro-Hungarian Empire and by artists like Schiele. He was initially declared unfit for combat duty but was eventually conscripted into the Austrian army in June 1915, just days after his marriage to Edith. His military service, however, did not involve front-line combat. Due to his artistic reputation and connections, he was assigned relatively safe duties, initially involving clerical work and guarding Russian prisoners of war in camps near Vienna.

This experience provided him with new subject matter. He produced numerous drawings and watercolors of Russian POWs, capturing their resignation, dignity, and the bleakness of their situation. These works, such as Russian War Prisoner (1915), are notable for their empathetic portrayal of the enemy soldiers, focusing on their shared humanity rather than nationalistic fervor. His time in the service also allowed him to continue painting. He was eventually transferred to the Imperial Royal Army Museum in Vienna in 1917, where his duties involved documenting the war effort and organizing exhibitions, giving him more time and resources for his own art.

The war years saw a subtle evolution in Schiele's style. While retaining his core Expressionist intensity, some works from this period exhibit a slightly greater solidity of form and a more detailed approach to composition, perhaps reflecting a search for stability amidst the chaos of war. He continued to produce powerful portraits and self-portraits, but also turned to landscapes and allegorical themes reflecting the anxieties of the time. Works like Decaying Mill (1916) or Town and River (1917) use landscape to convey mood, often tinged with melancholy or a sense of desolation that resonated with the wartime atmosphere. The war undoubtedly deepened his preoccupation with mortality and human suffering, themes already central to his work but now amplified by the surrounding conflict.

Final Years and Tragic Death

By 1918, despite the ongoing war, Egon Schiele seemed poised for major success. His mentor, Gustav Klimt, died in February of that year from a stroke and pneumonia, leaving Schiele arguably as the leading figure of the Viennese avant-garde. In March 1918, the 49th exhibition of the Vienna Secession was largely devoted to Schiele's work. He designed the poster for the exhibition (depicting himself and fellow artists seated around a table, titled Friends), and his paintings dominated the main hall. The exhibition was a critical and commercial triumph, selling numerous works and solidifying his reputation. He received portrait commissions and seemed on the brink of international recognition.

However, this period of triumph was tragically short-lived. In the autumn of 1918, the devastating Spanish Flu pandemic swept across Europe, killing millions already weakened by years of war. Edith Schiele, who was six months pregnant with their first child, contracted the illness and died on October 28, 1918. Grief-stricken, Egon Schiele himself succumbed to the same pandemic just three days later, on October 31, 1918. He was only 28 years old.

His final days were spent sketching his dying wife, capturing the devastating reality of loss with the same unflinching honesty that characterized his art. His own death cut short a career that, despite its brevity, had already produced a remarkably mature and influential body of work. The unfinished painting The Family, depicting himself, Edith, and the child they would never have, stands as a poignant testament to his final hopes and the abruptness of his end. His death, along with those of Klimt and the architect Otto Wagner in the same year, marked the end of an era for Viennese modernism.

Legacy and Art Historical Significance

Egon Schiele's position in art history is firmly established as one of the most important exponents of Austrian Expressionism and a key figure in early 20th-century modern art. Despite a mature career spanning less than a decade, his output was prolific – comprising around 300 oil paintings and over 3,000 works on paper (watercolors and drawings). He is widely regarded as one of the greatest draftsmen of the modern era, his mastery of line being central to his expressive power.

His primary contribution lies in his radical and psychologically penetrating exploration of the human figure. Schiele pushed the boundaries of portraiture and self-portraiture, using distortion, exaggerated gestures, and raw linearity to convey intense inner states – anxiety, desire, suffering, alienation, and defiance. His unflinching focus on sexuality and mortality challenged societal taboos and expanded the thematic scope of modern art. While influenced by Klimt, Symbolism (like that of Ferdinand Hodler), and even earlier artists like Albrecht Dürer in his linear precision, Schiele forged a highly personal and instantly recognizable style that prioritized emotional truth over conventional beauty.

Schiele's influence extended beyond his immediate contemporaries. His intense subjectivity and focus on the body's expressive potential resonated with later artists. Figures associated with the School of London, such as Lucian Freud and Francis Bacon, share a similar preoccupation with the raw, visceral depiction of the human form and psychological exposure, though their styles differ. Contemporary artists like Jenny Saville also engage with the body in ways that echo Schiele's confrontational approach. His work continues to fascinate and provoke, finding echoes in various cultural spheres, including photography, film, and fashion, where his aesthetic of angst and raw beauty is often referenced.

Museums worldwide hold his works, and major exhibitions continue to explore his art, confirming his enduring relevance. While his life was marked by controversy and ended prematurely, Egon Schiele's legacy is that of a fearless innovator who anatomized the human soul with unparalleled intensity, leaving behind a body of work that remains profoundly powerful and unsettlingly modern. He stands alongside Klimt and Kokoschka as a pillar of Austrian modernism, but his unique vision secured him a distinct and lasting place in the broader narrative of 20th-century art.

Conclusion

Egon Schiele's art remains a potent force, compelling viewers with its raw emotional honesty and stylistic audacity. In his short, turbulent life, he navigated the complex cultural landscape of early 20th-century Vienna, absorbing the influences of the Secession and his mentor Klimt, only to forge a path uniquely his own. Through his distorted figures, searing lines, and intense psychological portraits, he laid bare the anxieties and desires of the modern individual. His confrontations with societal norms, his legal troubles, and his tragic early death contribute to his mythic status, but it is the enduring power of his art – its ability to explore the depths of human vulnerability, sexuality, and mortality with unflinching intensity – that secures his vital position in the history of art. Schiele did not just paint the human body; he painted the human condition in all its fragile, fraught, and fervent reality.