Ferencz Franz Eisenhut stands as a significant figure in late 19th-century European art, a prominent exponent of both Academic Realism and the captivating allure of Orientalism. A Hungarian national with German roots, his meticulous technique, vibrant palette, and dedication to ethnographic detail earned him considerable acclaim during his lifetime. His canvases, often depicting bustling marketplaces, dramatic historical events, and intimate scenes of Eastern life, offer a window into a world that fascinated many Europeans of his era, while also contributing to Hungary's burgeoning national artistic identity.

Early Life and Artistic Awakening

Born on January 25, 1857, in Nova Palanka (Deutsch Palanka or Németpalánka), a town in the Bačka region of the Kingdom of Hungary (then part of the Austrian Empire, now Bačka Palanka, Serbia), Ferencz Eisenhut, also known as Franz Eisenhut, hailed from a German-speaking family. His father, Georg Eisenhut, was a merchant, and it was initially hoped that young Ferencz would follow a similar commercial path. However, the call of art proved stronger.

His innate talent for drawing did not go unnoticed. The Hungarian landscape painter Károly Telepy (1828–1906), a respected artist in his own right, recognized Eisenhut's potential during a visit to Palanka. Telepy's encouragement was pivotal, persuading Eisenhut's family to allow him to pursue formal artistic training. This support set him on a path that would lead him away from the mercantile world and into the heart of European artistic circles.

Formal Training: Budapest and Munich

Eisenhut's formal artistic education began in 1875 at the Hungarian Royal Drawing School (Magyar Királyi Mintarajztanoda és Rajztanárképezde) in Budapest, the precursor to the Hungarian University of Fine Arts. Here, he would have been immersed in the foundational principles of academic art, focusing on drawing from casts, life models, and the study of anatomy and perspective. This institution, under figures like Bertalan Székely and Károly Lotz, was crucial in shaping a generation of Hungarian artists.

After two years in Budapest, from 1875 to 1877, Eisenhut sought to further refine his skills at one of Europe's leading art centers: Munich. He enrolled in the prestigious Royal Academy of Fine Arts (Akademie der Bildenden Künste München). The Munich Academy was a magnet for aspiring artists from across Europe and America, renowned for its rigorous training in historical painting and realism. Influential figures like Wilhelm von Kaulbach and Karl von Piloty had established its reputation.

In Munich, Eisenhut had the distinct advantage of studying under Gyula Benczúr (1844–1920). Benczúr was a highly esteemed Hungarian historical painter, himself a product of the Munich Academy under Piloty, and a leading figure in Hungarian academic art. Benczúr's influence on Eisenhut would have reinforced the importance of meticulous draughtsmanship, rich color, and the grand manner of historical compositions. Other notable painters associated with the Munich School around this period, or slightly earlier, who contributed to its artistic milieu included Wilhelm Leibl, Franz von Lenbach, and the Austrian Hans Makart, whose opulent style also had a wide impact.

The Lure of the Orient: Travels and Inspiration

Upon completing his studies, Eisenhut, like many artists of his generation, felt an irresistible pull towards the "Orient"—a term then used broadly to describe regions of North Africa, the Middle East, and the Caucasus. This fascination was fueled by a desire for the exotic, the picturesque, and subjects perceived as untouched by Western industrialization. His first significant journey, around 1883-1884, took him to the Caucasus, visiting places like Tbilisi and Baku. These travels were not mere sightseeing expeditions; they were immersive experiences that provided him with a wealth of sketches, photographs, and artifacts that would inform his work for years to come.

Subsequent journeys took him to Egypt, Tunisia, Syria, and other parts of the Ottoman Empire. He was particularly drawn to the vibrant street life, the diverse cultures, and the dramatic landscapes. Unlike some Orientalist painters who relied on studio props and imagination, Eisenhut prided himself on firsthand observation. He collected traditional costumes, weaponry, textiles, and everyday objects, which he used to ensure the authenticity of his depictions. This commitment to ethnographic accuracy became a hallmark of his style, lending his paintings a sense of immediacy and realism that captivated audiences.

The Orientalist movement itself was diverse, encompassing artists like the French master Jean-Léon Gérôme, known for his highly polished, almost photographic detail; Eugène Delacroix, whose romantic and dynamic depictions of North Africa had an earlier, profound impact; and later figures such as Ludwig Deutsch and Rudolf Ernst, Austrian painters who, like Eisenhut, specialized in meticulously detailed genre scenes of Arab life. John Frederick Lewis, an English painter, was renowned for his intricate watercolors of Cairo. Eisenhut's work fits within this tradition of detailed, observational Orientalism, though often with a particular focus on narrative and human interaction.

Artistic Style: Academic Realism Meets Orientalist Themes

Eisenhut's artistic style was firmly rooted in the academic tradition. This meant a strong emphasis on correct drawing, balanced composition, smooth brushwork, and a high degree of finish. His figures are solidly rendered, and his attention to detail, whether in the texture of a carpet, the gleam of metalwork, or the intricacies of a traditional garment, is remarkable.

Within this academic framework, his primary subject matter was Orientalist. He excelled at capturing the atmosphere of bustling souks, the quiet dignity of desert encampments, the intensity of tribal gatherings, and moments of everyday life. His paintings often tell a story, inviting the viewer to imagine the lives and emotions of the people depicted. Works like Marketplace, Morocco (1888) or The Storyteller showcase his ability to create lively, populated scenes filled with character and incident.

His palette was rich and vibrant, reflecting the bright sunlight and colorful attire of the regions he visited. He skillfully used light and shadow to create depth and drama, highlighting key figures or architectural elements. While his approach was generally realistic, there was often an underlying romanticism in his choice of subjects and his portrayal of Eastern cultures, a common characteristic of much 19th-century Orientalist art. He was less inclined towards the overtly sensual or stereotypical harem scenes favored by some of his contemporaries, often focusing instead on public life, craftsmanship, and moments of communal activity.

Masterpieces and Major Works

Ferencz Eisenhut produced a significant body of work, but several paintings stand out for their ambition, scale, and impact.

The Battle of Zenta (Zentai csata, 1896)

Perhaps his most famous and monumental work, The Battle of Zenta was commissioned for the Hungarian Millennial Celebrations of 1896, which marked a thousand years since the Hungarian conquest of the Carpathian Basin. The painting depicts the decisive victory of the Habsburg-led Christian forces under Prince Eugene of Savoy over the Ottoman army in 1697. Measuring an impressive 7 by 4 meters (approximately 23 by 13 feet), it is one of the largest oil paintings in the Balkans.

Eisenhut meticulously researched the historical details, from the uniforms and weaponry to the topography of the battlefield. The composition is dynamic and dramatic, capturing the chaos and heroism of the conflict. The painting was a patriotic tour de force, celebrating a pivotal moment in Hungarian and European history where Ottoman expansion was decisively checked. It found its permanent home in the grand ceremonial hall of the Sombor Town Hall (Županija) in Sombor, Serbia, a testament to the region's historical significance within the former Kingdom of Hungary. The creation of such large-scale historical paintings was a hallmark of academic artists like Benczúr and his teacher Piloty, and Eisenhut proved himself a master of this demanding genre.

Death of Gül Baba (Gül Baba halála)

Another significant historical and Orientalist work is the Death of Gül Baba. Gül Baba ("Father of Roses") was an Ottoman Bektashi dervish poet and companion of Sultan Suleiman the Magnificent. He participated in several Ottoman campaigns in Europe and died in Buda (now part of Budapest) in 1541, shortly after the Ottoman conquest of the city. His tomb in Budapest remains an important site of pilgrimage. Eisenhut's painting captures the solemnity and reverence surrounding the death of this respected figure, combining historical narrative with his characteristic attention to Oriental detail.

Slave Trade (Népügyezők)

This work tackles a more challenging and somber aspect of the Orient, depicting a slave market. Such scenes were not uncommon in Orientalist art, often appealing to Western abolitionist sentiments or, sometimes, to a more voyeuristic interest. Eisenhut's treatment would likely have focused on the human drama and the ethnographic details of the setting and participants.

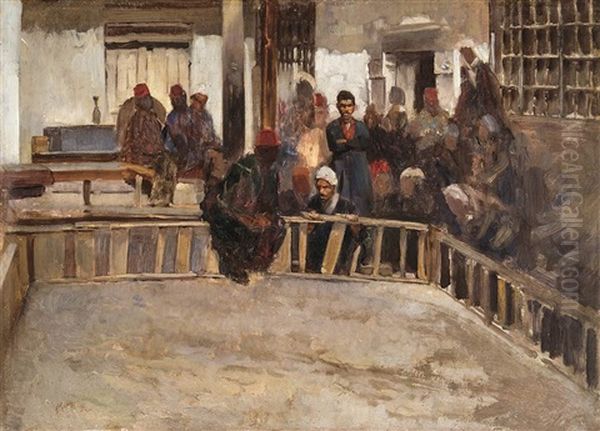

Cockfight (Véres kakasviadal)

Scenes of local customs and entertainment were popular Orientalist subjects. A cockfight provided an opportunity for dynamic composition, the depiction of intense emotion in both the animals and the spectators, and the rendering of diverse local characters. This theme was also explored by other Orientalists, such as Jean-Léon Gérôme.

Panorama for the Hungarian Royal Dome Theatre (1897)

Beyond easel paintings, Eisenhut also undertook large-scale decorative projects. He painted a panoramic work depicting a parade scene from June 8, 1897, for the Hungarian Royal Dome Theatre (Királyi Kupolaterem). This work, now housed in the Hungarian National Gallery, demonstrates his versatility and his engagement with contemporary national events.

His oeuvre also includes numerous other genre scenes, portraits, and studies, such as Healing with the Koran, An Arab School, The Sword Polisher, and A Difficult Passage. These works consistently display his technical skill and his deep engagement with his chosen subjects.

Exhibitions, Recognition, and the Munich Base

Eisenhut's work gained considerable recognition across Europe. He exhibited regularly in major art centers, including Budapest, Munich, Paris (at the Salon), Vienna, and Madrid. His paintings were sought after by collectors and museums, and he received several awards and honors for his contributions to art.

Munich remained his primary base of operations for much of his career. The city's vibrant artistic community, its excellent academy, and its international connections provided a supportive environment for an artist with his ambitions. He was part of a generation of artists who, while maintaining strong ties to their home countries, participated in a broader European artistic culture. Other Hungarian artists who found success or spent significant time in Munich included the celebrated Mihály Munkácsy (though his primary base became Paris) and Pál Szinyei Merse, whose plein-air innovations offered a contrast to the academic mainstream.

Eisenhut's success can be attributed not only to his technical prowess but also to his ability to tap into the prevailing European fascination with the Orient. His works offered viewers an escape, a glimpse into cultures perceived as exotic, ancient, and alluringly different. He also contributed to the visual culture of Hungary, particularly through works like The Battle of Zenta, which resonated with national pride and historical consciousness.

The Artist's Working Methods and Personal Life

Eisenhut was known for his diligent working methods. His travels were not just for inspiration but also for intensive study. He made numerous sketches from life, took photographs (a tool increasingly used by artists in the late 19th century for reference), and collected artifacts. This dedication to authenticity lent a convincing quality to his studio productions. Artists like Gérôme were also known to use photography extensively.

In 1897, Eisenhut returned to his birthplace, Palanka, for a significant personal event: his marriage. This connection to his hometown remained despite his international career. He continued to paint prolifically, dividing his time between his studio in Munich and his travels.

It's interesting to note the anecdote about his father's initial wish for him to become a merchant. This is a common narrative in the biographies of many artists – the struggle between familial expectations and an undeniable artistic calling. Eisenhut's success ultimately validated his choice of profession.

There is no strong evidence to suggest extensive collaborations with other painters in the sense of co-authoring artworks, though the academic environment, particularly in Munich, fostered a sense of community and shared learning. His primary artistic relationship in terms of direct influence was his tutelage under Gyula Benczúr.

Later Years and Legacy

Ferencz Franz Eisenhut's productive career was tragically cut short. He died relatively young, on June 2, 1903, in Munich, at the age of 46. He was buried in Munich's Ostfriedhof (East Cemetery).

Despite his premature death, Eisenhut left behind a substantial and significant body of work. He is remembered as one of the foremost Orientalist painters of the Austro-Hungarian Empire and a key figure in Hungarian academic art. His paintings are held in numerous public and private collections, including the Hungarian National Gallery in Budapest, the Sombor Town Hall, and various museums across Europe.

His legacy lies in his skillful fusion of academic technique with the captivating subject matter of the Orient. He provided his contemporaries with vivid, detailed, and often romanticized visions of distant lands, while also contributing to the historical and national art of Hungary. His work reflects the broader cultural currents of the late 19th century: the rise of nationalism, the colonial encounters that fueled Orientalism, and the enduring appeal of meticulous realism in academic art.

While artistic tastes shifted dramatically with the advent of modernism in the early 20th century, there has been a renewed appreciation for the technical skill and cultural insights offered by academic and Orientalist painters like Eisenhut. His works continue to be studied for their artistic merit, their historical context, and the complex interplay of observation, imagination, and cultural representation that defines them. He remains a testament to a period when the meticulous rendering of the visible world, combined with a fascination for the exotic, held a powerful sway over the European artistic imagination, and artists like Jean Discart, Charles Wilda, and the aforementioned Osman Hamdi Bey (an Ottoman intellectual and painter himself, offering a unique "insider" perspective on Orientalist themes) explored similar terrains. Eisenhut's contribution is a distinct and valuable part of this rich artistic tapestry.