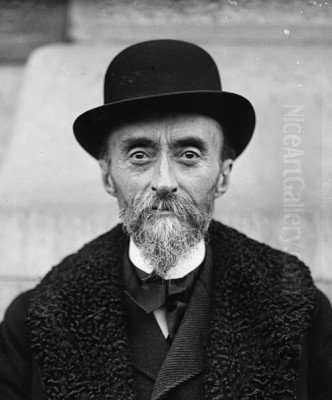

Fernand Cormon stands as a significant, albeit sometimes overlooked, figure in the landscape of late nineteenth and early twentieth-century French art. Officially Fernand-Anne Piestre, he adopted the surname Cormon, likely from his playwright father. Born into the vibrant cultural heart of Paris on December 24, 1845, he evolved into a highly respected painter, muralist, and, perhaps most consequentially, an influential art educator. His career navigated the complex currents of an era defined by the entrenched power of the Academy and the burgeoning waves of modernism. Cormon himself was a master of the academic style, particularly historical painting, yet his studio became a crucible where some of the most revolutionary artists of the next generation honed their skills, creating a fascinating paradox that defines his legacy. He was a man of the establishment who inadvertently helped nurture its challengers.

Early Life and Artistic Formation

Fernand Cormon's entry into the world was marked by the artistic milieu of Paris. His father, Eugène Cormon (Pierre-Étienne Piestre), was a successful playwright, and his mother, Charlotte Furais, was an actress. This theatrical background may have subtly influenced his later penchant for dramatic compositions and narrative clarity in his paintings. While Paris would be the ultimate stage for his career, his formal artistic training began not in the French capital, but in Brussels.

In Belgium, the young Cormon studied under Jean-François Portaels, a painter known for his Orientalist themes and portraits, who had himself been a student of Paul Delaroche. Portaels provided Cormon with a solid foundation in academic technique. Following this initial training, Cormon returned to Paris, the undisputed center of the Western art world, to further refine his craft.

He enrolled in the prestigious École des Beaux-Arts, the bastion of academic tradition. There, he entered the ateliers of two prominent masters: Alexandre Cabanel and Eugène Fromentin. Cabanel was a dominant figure in the French art establishment, celebrated for his historical, classical, and religious subjects, executed with polished precision – his Birth of Venus (1863) had been a major success at the Salon and was purchased by Napoleon III. Fromentin, on the other hand, was known both as a painter, particularly of Orientalist scenes capturing the light and atmosphere of North Africa, and as a writer and art critic. Studying under these distinct personalities exposed Cormon to different facets of academic painting, from Cabanel's smooth finish and idealized forms to Fromentin's more painterly approach and focus on exotic locales. This rigorous training instilled in Cormon a deep respect for drawing, composition, and historical accuracy, principles that would underpin his entire artistic output.

Rise to Prominence: The Paris Salon

The Paris Salon, the official art exhibition sponsored by the French state and overseen by the Académie des Beaux-Arts, was the primary venue for artists seeking recognition, patronage, and career advancement in the nineteenth century. Success at the Salon could launch a career, while rejection could stall it indefinitely. Cormon made his debut at this critical institution in 1868.

His early submissions quickly garnered attention, often due to their dramatic and sometimes violent subject matter. Works like Murder in the Seraglio (1868) and The Death of Ravana, King of Lanka (1875), now housed in the Musée des Beaux-Arts de Toulouse, showcased his flair for theatricality and his ability to handle complex, multi-figure compositions. These paintings, while adhering to academic standards of finish and detail, possessed a certain sensationalism that appealed to public taste and caught the eye of critics.

Cormon proved adept at navigating the Salon system. He understood the expectations of the jury, which typically favored large-scale historical, religious, or mythological scenes rendered with technical proficiency and moral clarity. His ability to deliver works that met these criteria, while also injecting them with a degree of dramatic intensity, allowed him to build his reputation steadily throughout the 1870s. He became recognized as a rising talent within the academic fold, a painter capable of tackling ambitious themes with considerable skill.

Masterpiece and Controversy: Cain

The year 1880 marked a pivotal moment in Cormon's career with the exhibition of his monumental painting Cain (also known as Cain Fleeing with His Family or The Flight of Cain) at the Paris Salon. This powerful work depicted the biblical first murderer, haggard and haunted, leading his family through a desolate, primordial landscape after being cursed by God. The figures are rendered with stark realism and raw physicality, conveying exhaustion, fear, and the burden of guilt. The dramatic lighting and barren setting amplify the sense of divine punishment and exile.

The painting was an enormous success at the Salon. It was awarded the prestigious Medal of Honor, a significant accolade that cemented Cormon's status as a leading historical painter of his generation. The French state promptly acquired the work for the nation's collections, and it is now a highlight of the Musée d'Orsay in Paris.

However, Cain also sparked considerable discussion and controversy. Its brutal depiction of primitive humanity resonated with contemporary scientific and anthropological interests in human origins and prehistory, fueled by recent archaeological discoveries and Darwinian theories. Some critics saw the work as embodying the concept of "deep time," a geological and evolutionary timescale far exceeding traditional biblical chronologies. The painting's raw power and focus on the harsh realities of early human existence were seen by some as challenging, even subversive, despite its biblical subject matter. Cormon's Cain thus became more than just a successful Salon painting; it was a cultural touchstone reflecting the intellectual ferment of the era, grappling with questions of faith, science, and the nature of humanity.

Historical and Prehistoric Visions

Following the triumph of Cain, Cormon continued to explore historical, religious, and, notably, prehistoric themes. His interest in the distant past became a recurring feature of his work. He wasn't merely illustrating biblical stories or historical events; he sought to vividly reconstruct ancient worlds, drawing on available scientific and archaeological knowledge to inform his depictions.

His paintings often focused on moments of high drama or significant turning points in human history or myth. He aimed for a sense of authenticity, populating his canvases with figures whose physiques and attire reflected his understanding of the period, whether it be ancient Gaul, biblical times, or the Stone Age. This commitment to historical verisimilitude, combined with his skill in dramatic composition, made his works compelling visual narratives.

Works dealing with prehistory allowed Cormon to engage directly with the burgeoning fields of paleoanthropology and archaeology. He depicted scenes of early human life, hunting, tool-making, and migration, attempting to visualize the struggles and triumphs of humanity's ancestors. These paintings, while speculative, were grounded in the scientific understanding of the time and contributed to the popular visualization of the prehistoric past. They demonstrated his ability to adapt the grand manner of historical painting to novel subject matter, reflecting the expanding horizons of nineteenth-century knowledge.

Monumental Decorations: Murals

Beyond easel painting, Cormon undertook several major commissions for large-scale mural decorations, a prestigious genre that allowed artists to engage with public architecture and address grand themes. These projects further solidified his position within the French art establishment.

His most significant mural cycle was created for the National Museum of Natural History (Muséum national d'histoire naturelle) in Paris, specifically for the Gallery of Paleontology and Comparative Anatomy. Working between 1893 and 1898, Cormon collaborated with the architect Charles-Louis-Ferdinand Dutert, who designed the new gallery building. Cormon produced a series of ten monumental canvases depicting scenes from human prehistory, spanning the Stone Age to the Iron Age. These murals visualized early human evolution, tool use, hunting (including depictions of mammoths), and the development of early societies. They were designed to complement the museum's exhibits, providing dramatic visual context for the fossil remains and artifacts on display. This project perfectly aligned Cormon's interest in prehistory with a major public commission, showcasing his ability to work on an architectural scale and integrate his art within a scientific institution.

Cormon also received a commission to decorate the Town Hall (Mairie) of the 4th Arrondissement of Paris. For this civic building, he created a series of paintings in grisaille (monochromatic tones, often simulating sculpture) addressing fundamental aspects of human life and society: themes such as birth, death, marriage, war, education, and charity. These allegorical or historical scenes were intended to convey civic values and the functions of local government. His involvement in such public projects demonstrated his versatility and his acceptance by the official art institutions of the Third Republic. He may have also contributed decorations to other public buildings, such as the Petit Palais.

The Educator: Atelier Cormon

While Cormon achieved considerable success as a painter, his enduring influence arguably stems even more significantly from his role as a teacher. In the early 1880s, he opened his own private teaching studio, the Atelier Cormon, located at 104 Boulevard de Clichy in Montmartre, an area rapidly becoming the epicenter of Parisian artistic life. Private ateliers like Cormon's offered an alternative or supplement to the official training at the École des Beaux-Arts, often providing a more liberal atmosphere.

Cormon's reputation attracted a large and diverse group of students, both French and international. His teaching methods were rooted in the academic tradition he knew so well. He emphasized rigorous training in drawing, particularly life drawing from the nude model, which was considered the cornerstone of academic practice. He guided students in matters of composition, anatomy, and perspective, preparing them to create the kind of well-structured, technically proficient works favored by the Salon jury.

Accounts suggest Cormon was a conscientious and encouraging teacher, offering regular critiques and guidance. He aimed to equip his students with the technical skills necessary for a successful career within the established art system. However, unlike some rigidly conservative academic instructors, Cormon seems to have maintained a relatively liberal atmosphere in his studio. He did not necessarily forbid his students from exploring newer artistic trends developing outside the academic mainstream, even if he did not personally endorse them in his own work. This relative openness would prove crucial.

A Studio of Contrasts: Notable Students

The Atelier Cormon became a remarkable melting pot of artistic temperaments and future trajectories. While Cormon himself remained dedicated to academic historical painting, his studio paradoxically became a formative environment for artists who would radically challenge those very traditions.

Among his most famous pupils were figures central to Post-Impressionism and early Modernism. Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec studied with Cormon, developing his incisive drawing skills before dedicating himself to depicting the vibrant, gritty nightlife of Montmartre. Émile Bernard also passed through the studio, later becoming a key figure in the development of Cloisonnism and Synthetism alongside Paul Gauguin, reacting against the naturalism of Impressionism.

Perhaps the most famous, though brief, student was Vincent van Gogh. The Dutch artist spent a few months at the Atelier Cormon in 1886 after arriving in Paris. While Van Gogh found the academic emphasis on drawing from plaster casts stifling, his time there was significant. It was at Cormon's that Van Gogh met and befriended fellow students like Toulouse-Lautrec, Bernard, and Louis Anquetin. Anquetin himself was an innovative painter associated with Cloisonnism. This network of young, ambitious artists proved crucial for Van Gogh, exposing him to the latest Parisian art trends and stimulating his rapid stylistic evolution towards his characteristic Post-Impressionist style.

Other notable students who would make their mark included Henri Matisse, who studied briefly with Cormon before moving to the studio of Gustave Moreau. Francis Picabia, later a key figure in Dada and Surrealism, also received early training at the Atelier Cormon. The list extends further, including the Belgian painter Eugène Boch (whose portrait Van Gogh famously painted), Paul Tampier, Alphonse Osbert (who leaned towards Symbolism), the Swiss Marius Borgeaud, the Romanian Theodor Pallady, the talented Henri Émile Vollet, and decorative artists like Pierre Brissaud, Jacques Brissaud, and Charles Martin.

The presence of such diverse talents highlights the complex role of Cormon's studio. While he provided traditional academic instruction, the environment itself, situated in the heart of avant-garde Montmartre and populated by restless young artists, fostered experimentation and exchange. Many students absorbed the technical grounding Cormon offered but ultimately pursued radically different artistic paths, reacting against or transforming the very principles they learned in his atelier. Cormon, the academic master, thus inadvertently served as a catalyst for modern art.

Cormon's Artistic Style

Fernand Cormon's own artistic style remained largely consistent with the principles of French academic painting throughout his career. His work is characterized by strong, clear drawing, a legacy of his rigorous training. Compositions are carefully constructed, often featuring complex arrangements of figures within well-defined spatial settings. He possessed a talent for narrative clarity, ensuring that the stories or historical moments depicted in his paintings were legible and impactful.

His handling of paint was generally smooth and detailed, prioritizing finish and illusionism over visible brushwork, especially in his major Salon pieces. However, his work was not devoid of drama or emotion. He often chose subjects with inherent theatricality – battles, mythological crises, moments of intense human suffering or effort – and rendered them with a vigor that distinguished him from more staid academic painters. His use of color could be rich and descriptive, and he paid considerable attention to historical detail in costume and setting, lending an air of authenticity to his reconstructions of the past.

While he excelled in large-scale historical and religious canvases, Cormon also produced portraits and, later in his career, potentially other genres. His portraits were noted for their solid technique and psychological insight. Compared to the revolutionary changes being wrought by Impressionism and Post-Impressionism – movements focused on capturing fleeting moments, the effects of light, subjective experience, and formal innovation – Cormon's art represented the continuity of tradition. He remained committed to narrative, illusionism, and the hierarchy of genres that placed historical painting at the apex. Yet, within that tradition, he was a powerful and respected practitioner.

Later Career and Recognition

Fernand Cormon continued to be a prominent figure in the official French art world well into the twentieth century. His success as both a painter and teacher brought him numerous honors and prestigious appointments. In 1898, he was elected to the highly esteemed Académie des Beaux-Arts, taking the seat previously held by Eugène Lenepveu. This election confirmed his status as one of France's leading academic artists.

He also became a professor at the École des Beaux-Arts, the very institution where he had trained, allowing him to transmit his knowledge and principles to a new generation of students within the official system. He was made an Officer of the Legion of Honour in 1889, further recognition from the French state.

He continued to exhibit at the Salon and undertake commissions. While the avant-garde movements were increasingly capturing critical and public attention, Cormon remained a respected representative of the academic tradition, which still held considerable sway, particularly in official circles and public commissions. He maintained connections with other established artists and figures in the cultural world, though perhaps less so with the radical innovators, some of whom had passed through his own studio. He died in Paris on March 20, 1924, reportedly as a result of a traffic accident.

Legacy and Influence

Fernand Cormon's legacy is multifaceted. In his own time, he was celebrated as a master of historical painting, admired for his technical skill, dramatic compositions, and ability to tackle grand themes, particularly those related to French history and the origins of humanity. His major works, like Cain and the murals for the Museum of Natural History, remain significant examples of late nineteenth-century academic art and its engagement with history and science.

However, his most profound and lasting influence arguably lies in his role as an educator. The Atelier Cormon was a crucial training ground for an extraordinary number of artists who would shape the course of modern art. While many of these students, including Van Gogh, Toulouse-Lautrec, Bernard, Matisse, and Picabia, ultimately rejected the academic principles Cormon espoused, their time in his studio provided them with essential technical grounding and, perhaps more importantly, a place to connect with fellow artists and engage with the vibrant artistic debates of Paris. Cormon's studio acted as an unexpected crossroads between tradition and innovation.

After his death, Cormon's reputation, like that of many academic painters of his generation, somewhat faded as modernist aesthetics came to dominate art history narratives. He was often remembered primarily as the teacher of more famous avant-garde artists. However, recent decades have seen a renewed interest in nineteenth-century academic art, leading to a more nuanced appreciation of figures like Cormon. Art historians now recognize his skill as a painter within his chosen tradition and acknowledge the complex, often paradoxical, role he played in the artistic ecosystem of his time. He was a pillar of the establishment whose studio became a fertile ground for rebellion, a master of historical narrative in an age increasingly focused on subjective experience, and a dedicated teacher whose influence extended far beyond his own stylistic boundaries.

Conclusion

Fernand Cormon occupies a unique position in the annals of French art. He was a highly successful product of the academic system, achieving fame and recognition through his mastery of historical painting and his significant public commissions. His works, characterized by technical skill, dramatic flair, and engagement with grand historical and prehistoric themes, earned him a place among the leading artists of the French Third Republic.

Simultaneously, his role as the head of the Atelier Cormon connects him directly to the revolutionary movements that would define modern art. By providing rigorous training within a relatively open environment in the heart of Montmartre, he inadvertently fostered the development of artists like Van Gogh, Toulouse-Lautrec, and Bernard, who would take art in entirely new directions. Fernand Cormon's career thus embodies the tensions and transitions of a pivotal era in art history, standing as a testament to the enduring power of tradition even as it served as a launching pad for radical innovation. He remains a key figure for understanding the complex interplay between the Academy and the avant-garde at the turn of the twentieth century.