Henry Bacon stands as a significant, though perhaps sometimes overlooked, figure in the landscape of nineteenth-century American art. Born in Haverhill, Massachusetts, in 1839, his life and career traced a fascinating path from the battlefields of the American Civil War to the prestigious art academies of Paris, and ultimately to the sun-drenched landscapes of Egypt. Primarily celebrated for his evocative watercolors, Bacon captured the nuances of life aboard transatlantic liners and the exotic allure of the Near East, developing a distinctive style that blended academic precision with a keen sensitivity to light and atmosphere. His journey reflects the experiences of many American artists of his generation who sought training and inspiration abroad, contributing to the rich transatlantic dialogue that shaped American art in the post-Civil War era. He passed away in Cairo, Egypt, in 1912, leaving behind a body of work that documents his travels and his artistic evolution.

Early Life and the Crucible of War

Henry Bacon's formative years were marked by the tumultuous period of the American Civil War. Born into a New England environment, his early inclinations towards art were soon interrupted by the call to duty. He enlisted in the Union Army, serving as a field artist for Leslie's Weekly, one of the prominent illustrated newspapers of the time. This role placed him directly in the midst of conflict, tasked with documenting the events and scenes of war for a public hungry for visual information.

His time as a soldier-artist provided him with firsthand experience of the realities of war, a theme that would occasionally surface in his later work, albeit often viewed through a lens of memory and reflection. Like other artists who documented the war, such as Winslow Homer, Edwin Forbes, and Alfred Waud, Bacon's early sketches were likely characterized by immediacy and reportorial accuracy, honed under challenging conditions. This period undoubtedly sharpened his observational skills and his ability to capture human figures and dramatic situations quickly.

Bacon's military service was not without personal cost. He sustained injuries during the conflict, an experience that would ultimately influence his decision, alongside his wife Lizzie, to leave the United States after the war's conclusion. Seeking perhaps a different environment for recovery and artistic development, they set their sights on Europe, particularly Paris, which was rapidly becoming the undisputed center of the Western art world. This move marked a pivotal transition from the raw documentation of war to the pursuit of formal artistic training.

Parisian Training: The École des Beaux-Arts

Arriving in Paris, Henry Bacon embarked on the next crucial phase of his artistic development. He achieved the distinction of being among the first wave of American artists admitted to the prestigious École des Beaux-Arts, the official French academy of art. This institution represented the pinnacle of traditional, state-sponsored art education, emphasizing rigorous training based on classical principles and the hierarchy of genres, with history painting at its apex.

At the École, Bacon studied under respected academic painters Alexandre Cabanel and Edouard Frère. Cabanel was a highly successful artist known for his historical, classical, and religious subjects, executed with polished technique and appealing to the tastes of the French establishment, exemplified by his famous Birth of Venus (1863). Frère, while also an academic painter, was known more for his sentimental genre scenes depicting rural life. Under their tutelage, Bacon received a thorough grounding in drawing, anatomy, perspective, and composition – the hallmarks of conservative, late nineteenth-century French academicism.

This environment was both challenging and stimulating. Bacon was immersed in a system that valued technical mastery and adherence to established conventions. He would have competed alongside French students and a growing number of international artists flocking to Paris. Figures like Jean-Léon Gérôme and William-Adolphe Bouguereau were dominant forces at the Salon, the official annual exhibition, setting the standards for academic success. Bacon's training under Cabanel and Frère placed him firmly within this traditionalist camp, shaping his early approach to subject matter and technique, even as he later developed his own distinct voice. Other American artists like John Singer Sargent, James McNeill Whistler, Mary Cassatt, and Thomas Eakins also sought training in Paris around this period, though their paths and artistic responses would diverge significantly.

Developing a Style: Genre and Early Works

Following his formal training at the École des Beaux-Arts, Henry Bacon began to establish his artistic identity. His early works naturally reflected the academic principles he had absorbed. He focused initially on genre scenes and historical subjects, often executed with the polished finish and careful composition favored by his teachers like Alexandre Cabanel. An example from this period might include works depicting historical vignettes or carefully rendered scenes of everyday life, demonstrating his technical proficiency acquired in Paris.

His painting The Boston Boys and General Gage (1775), dating from 1875, exemplifies this phase. It tackles an American historical subject, depicting an encounter during the pre-Revolutionary period in Boston. The style adheres to academic conventions, with clear narrative, detailed rendering of figures and costumes, and balanced composition. Such works aimed for legibility and a certain historical or moral weight, aligning with the expectations of Salon juries and traditional patrons on both sides of the Atlantic.

However, Bacon did not remain solely focused on oil painting or historical themes. He increasingly turned his attention to watercolor, a medium gaining popularity and respectability during the nineteenth century. While academic training often prioritized oil painting, Bacon found watercolor particularly suited to capturing fleeting effects of light and atmosphere, which would become central to his later work. This shift also coincided with a move away from purely historical subjects towards more contemporary scenes, particularly those related to travel and leisure. His French training provided a solid foundation, but his evolving interests began to lead him in new directions.

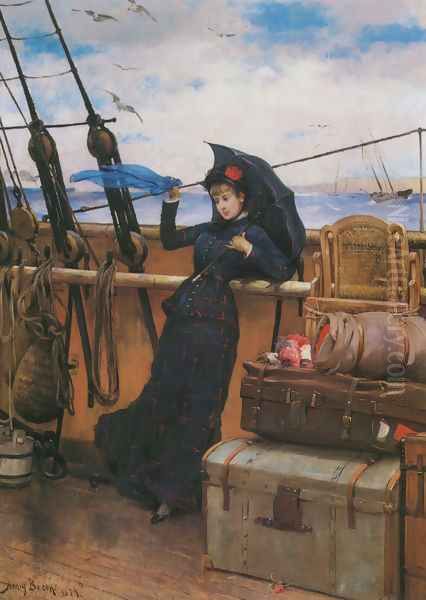

The Allure of the Sea: Shipboard Scenes

A distinctive and popular aspect of Henry Bacon's oeuvre emerged with his depictions of life aboard transatlantic steamships. As travel between America and Europe became more common in the latter half of the nineteenth century, the ocean liner itself became a unique social space and a compelling subject for artists interested in modern life. Bacon excelled in capturing the atmosphere of these voyages, focusing on the interactions of passengers, the play of light on the decks and water, and the vastness of the surrounding ocean.

His watercolors and paintings of shipboard scenes often showcase his skill in perspective, rendering the receding lines of the deck and railings to create a convincing sense of space. He paid close attention to the effects of light and weather – the glint of sun on brass fittings, the haze of a misty morning at sea, the deep shadows cast by the ship's superstructure. These works frequently feature elegantly dressed figures, capturing moments of conversation, contemplation, or anticipation, such as in First Sight of Land.

These scenes resonated with an audience familiar with or aspiring to transatlantic travel. They offered glimpses into a world of relative leisure and sophistication, tinged with the romance and sometimes the melancholy of a long sea journey. While artists like Winslow Homer also powerfully depicted the sea, often focusing on its raw power and the relationship between humanity and nature, Bacon's shipboard scenes tend to emphasize the social dynamics and the contained environment of the vessel itself. His unique compositional choices, sometimes employing diagonal viewpoints or cropping figures in a manner perhaps influenced by photography or Japanese prints (influences becoming current in Paris), added a modern sensibility to these popular subjects.

Embracing Orientalism: Journeys to Egypt

A significant turning point in Henry Bacon's artistic journey was his embrace of Orientalism. Like many Western artists of the nineteenth century, he became fascinated by the cultures and landscapes of North Africa and the Middle East. This fascination was fueled by increased travel opportunities, colonial expansion, and a romanticized Western perception of the "Orient" as exotic, timeless, and sensual. Bacon began making regular winter trips to Egypt, seeking respite from colder climates and finding rich subject matter along the Nile River and in the bustling cities.

His decision to focus on Egypt placed him within a well-established tradition of Orientalist painting. French artists like Eugène Delacroix had pioneered the genre earlier in the century, followed by highly successful academic painters such as Jean-Léon Gérôme, whose meticulously detailed depictions of Egyptian and Middle Eastern life were immensely popular. Other artists, including the French painter Eugène Fromentin and the Austrian Ludwig Deutsch, also specialized in Orientalist scenes. American artists too, like Frederick Arthur Bridgman, found considerable success with similar subjects.

Bacon's approach to Orientalism focused less on dramatic historical reconstructions or overtly ethnographic documentation, and more on the atmospheric qualities of the Egyptian landscape and the daily life he observed. He was particularly drawn to the Nile, capturing scenes of traditional sailing vessels (dahabeahs), riverside villages, ancient ruins, and the unique quality of light in the desert environment. His time spent in Egypt provided a wealth of inspiration that would dominate his later career, allowing him to develop his skills in watercolor further and solidify his reputation as a painter of captivating foreign scenes.

Mastery of Watercolor: The Nile Landscapes

Egypt proved to be exceptionally fertile ground for Henry Bacon's development as a watercolorist. The clear, strong light, the vibrant colors of the local dress and markets, and the picturesque scenery along the Nile provided ideal subjects for the medium's transparency and luminosity. Bacon spent considerable time traveling along the river, often aboard traditional dahabeahs, which allowed him intimate access to riverside life and landscapes away from the main tourist centers.

His Egyptian watercolors are characterized by their atmospheric depth and sensitivity to light. He masterfully captured the haze of the desert heat, the reflections on the calm waters of the Nile, and the interplay of sunlight and shadow on ancient stone monuments and mud-brick villages. Works like On the Nile or Egyptian Dahabeah showcase his ability to render complex scenes with fluidity and precision. He often populated these landscapes with figures – local Egyptians engaged in daily activities, fellow travelers – integrating them naturally into the environment.

Bacon's technique in watercolor was refined and controlled, reflecting his academic background, yet it also possessed a freshness and immediacy appropriate to the medium. He utilized pure washes, allowed the white of the paper to represent highlights, and built up layers of color to achieve nuanced effects. His compositions continued to explore interesting perspectives, sometimes looking down from a height, using strong diagonals, or framing views in ways that felt spontaneous and observational. These Egyptian watercolors became some of his most sought-after works, admired for their technical skill and their evocative portrayal of a land that held great fascination for Western audiences. He successfully translated the grandeur and the everyday reality of Egypt into compelling visual narratives.

Exhibitions and Recognition

Throughout his career, Henry Bacon sought recognition through established channels, regularly submitting his work to major exhibitions in both Europe and the United States. His training at the École des Beaux-Arts prepared him for the competitive environment of the Paris Salon, the most important annual art exhibition in the world during much of the nineteenth century. Acceptance and positive notice at the Salon were crucial for an artist's reputation and commercial success. Bacon exhibited there, showcasing his genre scenes, shipboard paintings, and later, his popular Egyptian watercolors.

In the United States, he exhibited at the National Academy of Design in New York City, a prestigious institution modeled partly on European academies. He also likely showed work in Boston and other American cities. His participation in these venues ensured his visibility among American collectors, critics, and fellow artists. His watercolors, in particular, received praise for their technical accomplishment and appealing subject matter. The shipboard scenes catered to a taste for modern life and travel, while the Egyptian views tapped into the widespread interest in Orientalism.

While perhaps not achieving the same level of fame as some of his American contemporaries working abroad, like John Singer Sargent or Mary Cassatt, who engaged more directly with Impressionism and modern portraiture, Bacon carved out a successful niche for himself. He built a solid reputation as a skilled painter, particularly in watercolor, bridging the gap between traditional academic training and subjects drawn from contemporary life and travel. His consistent presence in major exhibitions solidified his standing as a professional artist contributing to the international art scene of his time.

Later Life and Legacy

In his later years, Henry Bacon continued to divide his time between Europe and Egypt, maintaining his focus on the subjects that had brought him recognition. After the death of his first wife, Lizzie, he married Louisa Lee Andrews. They established residences that facilitated his artistic practice, living for periods in London as well as continuing the essential winter journeys to Egypt, which remained his primary source of inspiration. He remained productive, creating watercolors that captured the enduring allure of the Nile and its surroundings.

Henry Bacon passed away in Cairo, Egypt, in 1912, at the age of 73. His death occurred in the land that had so profoundly shaped the latter part of his artistic career. His life's work reflects a journey typical of many artists of his generation: seeking foundational training in the academic centers of Europe, adapting that training to personal interests, and finding unique subject matter through travel. He successfully navigated the transatlantic art world, maintaining connections and exhibiting on both continents.

Today, Henry Bacon is remembered primarily for his watercolors, especially the shipboard and Egyptian scenes. His work offers valuable insights into the tastes and interests of the late nineteenth century, including the fascination with travel and exotic locales. His papers and archives, which include correspondence, writings, and business records, are preserved, offering researchers a window into his life and the practicalities of an artist's career during that period. While distinct from the avant-garde movements developing concurrently, Bacon's art represents a significant strand of American painting that engaged with international academic traditions while forging a personal style focused on careful observation and atmospheric effect. He remains an important figure among American expatriate artists who contributed to the richness and diversity of art in the Gilded Age.

Representative Works

Identifying specific, universally acknowledged "masterpieces" for Henry Bacon can be challenging, as his reputation rests more on the consistent quality and appealing subject matter of his output, particularly his watercolors. However, several works are frequently cited as representative of his style and thematic concerns:

The Boston Boys and General Gage (1875): An example of his earlier work in oil, tackling an American historical subject with academic clarity and narrative focus.

First Sight of Land (c. 1877): A quintessential shipboard scene, likely in watercolor, capturing the anticipation and social dynamics of transatlantic travel. Such works were popular for their depiction of modern leisure and elegant figures against the backdrop of the ocean.

The Departure (watercolor): Another example of his shipboard genre, focusing perhaps on the emotional moment of leaving port, showcasing his skill in rendering perspective and atmospheric conditions at sea.

On the Nile (various dates, watercolor): Not a single work, but a recurring theme. These watercolors depict scenes along the river – dahabeahs sailing, riverside villages, figures on the banks – characterized by luminous light and atmospheric perspective.

Egyptian Dahabeah (watercolor): Focusing specifically on the traditional Nile sailing vessel, these works often highlight the boat itself as a central element, set against the backdrop of the river and landscape, capturing the romance of Nile travel.

Paying the Scot (1870, oil): An earlier genre scene, likely reflecting his European training, depicting an interior narrative subject with careful attention to detail and character.

The Luck of Roaring Camp (after Bret Harte): Illustrating a scene from American literature, showing his engagement with narrative subjects beyond pure landscape or travelogue.

These examples illustrate the range of Bacon's work, from historical oils to his more characteristic watercolors of travel and Egyptian life. His strength lay in the evocative power of his watercolors, capturing specific moments and atmospheres with technical finesse.

Conclusion

Henry Bacon's artistic career charts a course from the battlefields of America to the heart of the Parisian art establishment and the exotic landscapes of Egypt. As one of the early Americans to study at the École des Beaux-Arts, he absorbed the rigors of academic training under figures like Alexandre Cabanel, which provided a lasting foundation for his work. Yet, Bacon forged his own path, finding particular success and a distinctive voice in the medium of watercolor. His shipboard scenes captured the essence of transatlantic travel, while his numerous views of Egypt, born from regular winter journeys, placed him firmly within the popular Orientalist tradition, albeit with a focus on atmosphere and observed daily life rather than grand historical narratives.

Though perhaps overshadowed by contemporaries who embraced more radical stylistic innovations like Impressionism, Bacon's contribution to American art is significant. He represents the accomplished academic painter who adapted traditional skills to new subjects and media, finding a receptive audience for his evocative watercolors of travel and exotic lands. Influenced by French academicism and contemporaries like Winslow Homer and perhaps even the light effects explored by Pierre-Auguste Renoir, he synthesized these elements into a pleasing and commercially successful style. His legacy resides in his beautifully rendered watercolors, which continue to offer compelling glimpses into the world of nineteenth-century travel and the enduring Western fascination with Egypt, executed with a skill honed in the ateliers of Paris and perfected under the African sun.