Ford Madox Brown stands as one of the most compelling, if sometimes enigmatic, figures in nineteenth-century British art. Though closely associated with the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood, he was never a formal member, carving out a unique path characterized by meticulous detail, moral conviction, and a profound engagement with the social and historical narratives of his time. His life and career were marked by a fierce independence, a complex artistic evolution, and a body of work that continues to fascinate and provoke.

Early Life and Continental Formation

Ford Madox Brown was born on April 16, 1821, in Calais, France, to English parents, Ford Brown, a retired ship's purser, and Caroline Madox. This French birth and his subsequent upbringing on the continent imbued him with a cosmopolitan perspective that distinguished him from many of his British contemporaries. His artistic education was thoroughly European, beginning in Bruges in 1835 under Albert Gregorius, a former pupil of the Neoclassical master Jacques-Louis David. He then studied in Ghent under Pieter van Hanselaere, and from 1837 to 1839, he was enrolled at the Antwerp Academy under the tutelage of Baron Gustaf Wappers, a prominent figure in Belgian Romanticism.

Wappers' influence, with its emphasis on dramatic historical scenes and rich colour, was significant, but Brown also absorbed the lessons of the Early Netherlandish masters like Jan van Eyck and Hans Memling, whose works he would have encountered in Bruges and Ghent. This early exposure to the meticulous realism and jewel-like colours of Northern Renaissance art would leave a lasting imprint on his style.

In 1840, Brown moved to Paris, where he continued his studies and was exposed to the vibrant contemporary art scene. He was particularly impressed by the Romantic canvases of Eugène Delacroix and Théodore Géricault, whose dramatic intensity and painterly freedom offered a contrast to the more rigid academic training he had received. It was also in Paris that he encountered the work of Paul Delaroche, known for his historically accurate and emotionally charged scenes. During this period, Brown began to develop his own voice, creating works that often explored literary and historical themes with a burgeoning sense of drama.

A pivotal moment in his early artistic development occurred during a visit to Rome in 1845-1846. There, he encountered the Nazarenes, a group of German Romantic painters, including Johann Friedrich Overbeck and Peter von Cornelius. The Nazarenes sought to revive the spiritual purity and artistic principles of the early Italian Renaissance, particularly the work of artists like Fra Angelico and Perugino. Brown was deeply impressed by their commitment to sincerity, their bright, clear colours, and their rejection of academic convention. This encounter encouraged him to lighten his palette and to strive for greater naturalism and emotional depth in his work, moving away from the darker, more theatrical style he had previously employed.

The Pre-Raphaelite Orbit

Upon his return to England in 1844, and more permanently after his time in Rome, Brown began to establish himself within the London art world. In 1848, a young Dante Gabriel Rossetti, captivated by Brown's painting The Abstract Representation of Justice (also known as Justice), sought him out as a teacher. Although Brown was only a few years older, Rossetti became his informal pupil. This marked the beginning of a lifelong, albeit sometimes complex, friendship and a crucial connection to the nascent Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood (PRB).

The PRB, officially formed in 1848 by Rossetti, William Holman Hunt, and John Everett Millais, aimed to reform British art by rejecting the perceived triviality and academicism of the Royal Academy, which they felt was overly influenced by the High Renaissance master Raphael. Instead, they advocated a return to the detailed observation, vibrant colour, and complex compositions of Quattrocento Italian and Flemish art.

While Brown shared many of the PRB's ideals – their commitment to "truth to nature," their interest in literary and moral subjects, and their meticulous technique – he never formally joined the Brotherhood. He was older, already possessed a distinct artistic identity forged on the continent, and perhaps valued his independence too highly. Nevertheless, he was a significant influence on the younger artists, particularly Rossetti, and his work was often exhibited alongside theirs and discussed in similar terms. He adopted their practice of painting on a white ground to achieve greater luminosity and embraced their detailed rendering of natural forms.

His relationship with the core PRB members varied. His bond with Rossetti was enduring, a mix of mutual artistic respect and personal affection. With Hunt and Millais, the connection was perhaps more professional than personal, though they shared common artistic goals. Brown's art, while aligning with Pre-Raphaelite principles in its intensity of observation and moral seriousness, often tackled broader social and historical themes than the more literary or religious subjects favored by some PRB members. He was, in essence, a fellow traveler, a sympathetic contemporary whose artistic aims resonated deeply with theirs, even as he maintained his distinct trajectory. The influential critic John Ruskin, a key champion of the PRB, also recognized Brown's talent, though their relationship was not always smooth.

Mature Style: Realism, Morality, and Meticulous Detail

Ford Madox Brown's mature style is characterized by its intense realism, often pushed to an almost hallucinatory clarity, a strong moral or narrative underpinning, and an extraordinary attention to detail. He was a slow and painstaking worker, often spending years on a single canvas. His compositions are frequently complex, packed with figures and symbolic elements that contribute to the overall meaning of the work.

His technique involved the use of bright, clear colours, often applied in small, precise brushstrokes, a method that owed something to his study of early Renaissance art and his association with the Pre-Raphaelites. He was particularly adept at rendering different textures and capturing the effects of light, often painting outdoors to achieve greater fidelity to nature, a practice also championed by the PRB.

A key characteristic of Brown's work is its narrative density. His paintings are rarely simple depictions; they are visual stories, often with a strong ethical or social message. He drew inspiration from literature, history, and contemporary life, and his figures are imbued with psychological depth and emotional intensity. This narrative impulse connects him to earlier British artists like William Hogarth, whose satirical and moralizing series also told complex stories through visual means.

Brown's commitment to realism extended beyond mere surface appearance. He sought to convey the underlying truth of his subjects, whether it was the harsh realities of Victorian labor, the emotional turmoil of emigration, or the complexities of historical events. This often led him to tackle unconventional or challenging themes, setting him apart from many of his contemporaries who favored more idealized or sentimental subjects. His figures possess a solidity and a psychological presence that makes them compelling and memorable.

Masterpiece: Work (1852-1865)

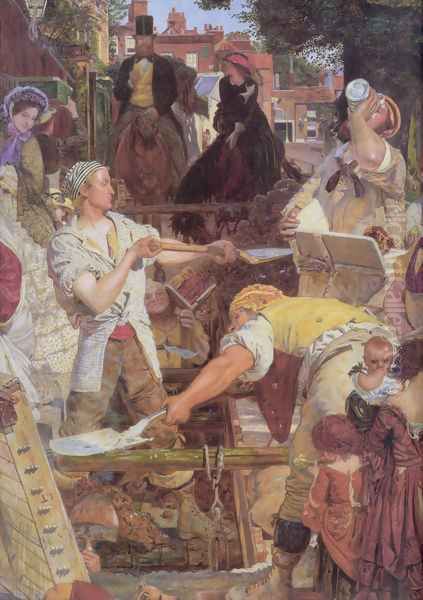

Perhaps Ford Madox Brown's most famous and ambitious painting is Work, a canvas he labored on for over a decade, from 1852 to 1865. This monumental painting, now in the Manchester Art Gallery, is a complex allegory of the Victorian social order and the dignity of labor. Set in Hampstead, London, it depicts a group of "navvies" (excavation workers) repairing a road, surrounded by representatives of various social classes.

The central figures are the muscular, sun-bronzed laborers, portrayed with a heroic realism that emphasizes their strength and vitality. Around them, Brown orchestrates a panorama of Victorian society. To the right stand two "brainworkers," the Christian Socialist F.D. Maurice and the writer Thomas Carlyle, who observe the scene, representing intellectual labor and social commentary. Carlyle, known for his writings on the value of work, was a personal acquaintance of Brown.

Other figures include an impoverished flower-seller, representing the urban poor; a group of ragged, orphaned children, cared for by their older sister; a wealthy lady and her daughter, whose fashionable attire contrasts with the workers' toil; and various street vendors and passersby. Even animals, like the navvies' dog and the pampered lapdogs of the wealthy, play their part in this social tapestry. The painting is crammed with detail, from the tools of the workers to the posters on the wall, all rendered with Brown's characteristic precision.

Work is more than just a depiction of labor; it is a profound meditation on the nature of work in all its forms – physical, intellectual, and even the "work" of idleness or social display. Brown's meticulous approach and the painting's complex symbolism invite prolonged contemplation. It is a testament to his ambition, his social conscience, and his ability to create a powerful and enduring image of his time. The painting was commissioned by Thomas Plint, a Leeds stockbroker and a significant patron of Pre-Raphaelite art, though Plint died before its completion.

Masterpiece: The Last of England (1852-1855)

Another of Brown's most iconic works is The Last of England, painted between 1852 and 1855 and now in the Birmingham Museum and Art Gallery (a smaller replica is in the Fitzwilliam Museum, Cambridge). This intensely poignant painting depicts a middle-class couple emigrating from England, presumably to Australia, driven by the economic hardships and lack of opportunity in their homeland. The inspiration for the painting came from the departure of Brown's close friend, the Pre-Raphaelite sculptor Thomas Woolner, who emigrated to Australia in 1852.

The painting is notable for its tondo (circular) format, which concentrates the viewer's attention on the central figures. The man and woman, modeled by Brown himself and his second wife, Emma Hill, sit huddled together on the deck of a ship, their faces etched with a mixture of stoicism, sorrow, and apprehension. The man stares resolutely ahead, while the woman, her hand protectively holding her husband's, gazes downwards, perhaps lost in thought or concealing her tears. A baby's hand, presumably their child's, is visible tucked inside her shawl.

The details are rendered with extraordinary precision: the texture of their clothes, the ropes and rigging of the ship, the distant white cliffs of Dover receding in the background. The cold, grey light and the choppy sea enhance the sense of desolation and uncertainty. Brown even painted parts of it outdoors in harsh weather to capture the authentic effects of light and atmosphere.

The Last of England is a powerful commentary on the phenomenon of emigration, a significant aspect of Victorian society. It captures the personal cost of leaving one's homeland and the courage required to face an unknown future. The painting's emotional intensity and meticulous realism make it one of the most moving images in British art. It speaks to themes of loss, hope, and the human condition that transcend its specific historical context.

The Manchester Murals (1879-1893)

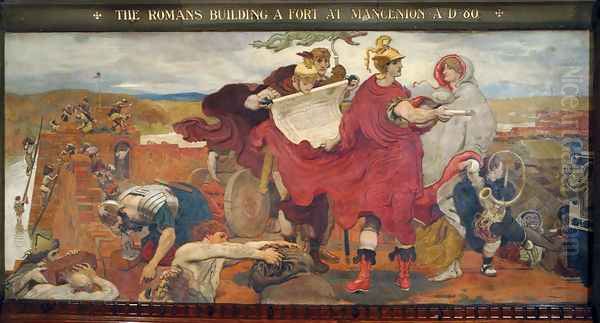

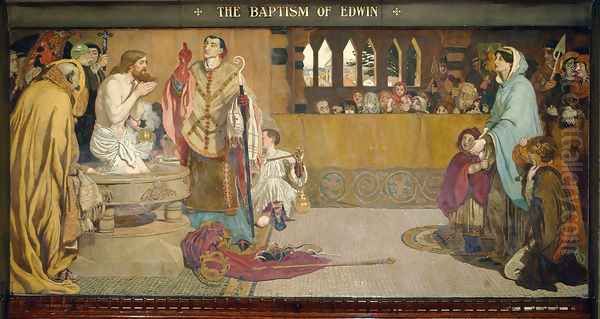

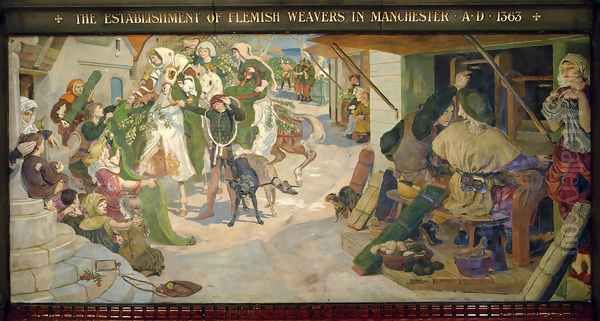

Towards the end of his career, Ford Madox Brown undertook another monumental project: a series of twelve large-scale murals for the Great Hall of Manchester Town Hall. Commissioned in 1878, these murals occupied him for the last fifteen years of his life. The series, collectively known as The Manchester Murals, depicts significant episodes in the history of the city, from Roman times to the Industrial Revolution.

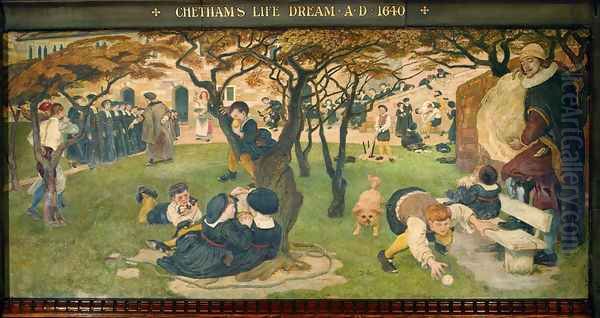

The subjects include The Romans Building a Fort at Mancenion, The Baptism of Edwin, The Expulsion of the Danes from Manchester, The Establishment of Flemish Weavers in Manchester, William Crabtree Observing the Transit of Venus, Chetham's Life Dream, Bradshaw's Defence of Manchester, and John Kay, Inventor of the Fly Shuttle. Each mural is a complex, multi-figure composition, researched with Brown's customary thoroughness and executed with his characteristic attention to detail and vibrant colour.

To ensure historical accuracy, Brown consulted with historians and antiquarians, and he meticulously studied period costumes and artifacts. The murals are not merely decorative; they are a visual chronicle of Manchester's development, celebrating its industrial prowess, its intellectual achievements, and its civic pride. They also reflect Brown's enduring interest in history as a source of compelling human drama and moral lessons.

The Manchester Murals represent a significant achievement in public art in Britain. They demonstrate Brown's versatility as an artist, his ability to work on a grand scale, and his commitment to creating art that was both aesthetically pleasing and intellectually engaging. Despite the physical demands of the project and his advancing age, Brown brought the series to a triumphant conclusion, with the final mural being installed shortly before his death. These works stand as a lasting monument to his skill and vision, and to the city they celebrate. Other artists who engaged in large-scale historical or public murals in the 19th century include William Bell Scott and Daniel Maclise, though Brown's Manchester series is particularly renowned.

Diversification: Design and Decorative Arts

Beyond his easel paintings and murals, Ford Madox Brown also made significant contributions to the decorative arts. In 1861, he became a founding partner in the design firm Morris, Marshall, Faulkner & Co., alongside William Morris, Dante Gabriel Rossetti, Edward Burne-Jones, Philip Webb, Peter Paul Marshall, and Charles Faulkner. This firm, often referred to simply as "Morris & Co.," was central to the Arts and Crafts Movement, which sought to revive traditional craftsmanship and to integrate art into everyday life.

Brown designed a wide range of items for the firm, including stained glass, furniture, tiles, and wallpaper. His designs often featured strong figural compositions, rich colours, and a medievalizing aesthetic that was characteristic of the Arts and Crafts style. Notable examples of his stained glass work can be found in various churches, including St Oswald's Church, Durham, and All Saints, Selsley. He designed robust, often painted, furniture, sometimes with narrative scenes, which contrasted with the more ornate and mass-produced furniture prevalent at the time.

His involvement with Morris & Co. reflects his belief in the social value of art and his desire to break down the traditional hierarchy between the "fine" arts and the "applied" arts. Like Morris and other members of the Arts and Crafts Movement, Brown believed that well-designed, handcrafted objects could enrich people's lives and contribute to a more beautiful and humane environment. His work in this field demonstrates his versatility and his commitment to artistic principles that extended beyond the confines of the picture frame. Other artists associated with the broader Arts and Crafts ethos, such as Walter Crane and C.F.A. Voysey, also contributed to this shift in design philosophy.

Challenges, Recognition, and Personal Life

Ford Madox Brown's career was not without its struggles. Despite his talent and originality, he often found it difficult to gain recognition from the established art institutions, particularly the Royal Academy, which consistently rejected his work. This lack of official validation contributed to periods of financial hardship and professional frustration. In 1865, in a bold assertion of his independence, Brown organized a solo retrospective exhibition of his work in Piccadilly, a pioneering move for an artist at the time, predating similar ventures by artists like Gustave Courbet in France.

His personal life was also marked by tragedy. His first wife, Elizabeth Bromley, died young in 1846, leaving him with a daughter, Lucy Madox Brown, who also became an artist and married William Michael Rossetti (Dante Gabriel's brother). His infant son from his second marriage to Emma Hill (who had been one of his models) died in 1857. His gifted son, Oliver Madox Brown, a promising painter and writer, died of blood poisoning in 1874 at the age of nineteen, a devastating blow to his father.

Despite these personal and professional challenges, Brown remained a resilient and dedicated artist. He was known for his somewhat irascible temperament but also for his loyalty to his friends and his commitment to his artistic principles. He was a man of strong social conscience, sympathetic to radical causes and concerned with the plight of the working classes, themes that often found expression in his art.

Later in his life, his reputation began to grow, particularly with the commission for the Manchester Murals, which brought him a measure of public acclaim. However, he never achieved the widespread fame or financial success of some of his contemporaries, such as Millais or Frederic Leighton.

Legacy and Historical Position

Ford Madox Brown died on October 6, 1893, in London. He left behind a body of work that is remarkable for its intensity, its intellectual depth, and its technical brilliance. While he was closely associated with the Pre-Raphaelites, his art transcends easy categorization. He was a bridge figure, connecting the Romanticism of his early training with the realism and social commentary that characterized much of his mature work.

His influence can be seen in the work of younger artists who shared his commitment to narrative and social realism. His meticulous technique and his emphasis on "truth to nature" aligned him with the Pre-Raphaelite ethos, but his broader range of subjects and his more overtly political or social concerns gave his work a distinctive edge. Artists like Luke Fildes and Hubert von Herkomer, who also depicted scenes of contemporary social life, can be seen as working in a tradition that Brown helped to establish in British art.

Today, Ford Madox Brown is recognized as one ofthe most important and original British painters of the Victorian era. His major works, such as Work and The Last of England, are considered masterpieces of nineteenth-century art, admired for their technical skill, their emotional power, and their insightful commentary on the society of their time. His contributions to the decorative arts through his association with Morris & Co. also secure his place within the history of the Arts and Crafts Movement.

His fierce independence, his willingness to tackle challenging themes, and his unwavering commitment to his artistic vision make him a compelling figure. He was an artist who engaged deeply with the world around him, using his art to explore the complexities of history, the realities of contemporary life, and the enduring themes of the human condition. The legacy of Ford Madox Brown is that of a singular talent, a painter of profound conviction whose work continues to resonate with viewers today. His art provides an invaluable window into the Victorian age, rendered with an honesty and intensity that remains strikingly modern.